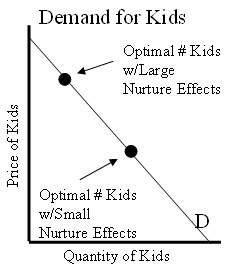

WSJ.com now features my target essay on my parental odyssey, replies by Laura Carroll and Will Wilkinson, and my replies to their replies. I successfully suppressed my urge to send a bunch of demand curves to the WSJ. But I thought EconLog readers might appreciate them.

The essence of my argument comes down to this:

In her reply, Laura Carroll raises the following objection:

Mr. Caplan’s thinking suggests that if I am contemplating whether I

want children or should have another one, learning that it can be

easier than I thought should swing the pendulum to “yes.” It assumes

that I do want a child–or more of them–but that I am letting worries

about the demands of parenting stop me. When contemplating having

children, we don’t all start with “I want them, but…” A growing number

of people know the experience of parenthood is not for them, “serene”

parenting option or not.

My response is that Carroll simply has an unusual demand curve. Apparently hers is vertical at Quantity=0, so it overlaps the y-axis:

That’s fine. I respect her preferences. But she ought to admit that she’s atypical. As I put it:

[M]ost people do feel some desire to be a parent. Many parents feel some desire to have another child. I’m directing my advice to them.

One of Will Wilkinson’s main challenges is best expressed graphically, too. Will’s words:

Suppose I’ve got my eye on a certain hi-definition television set. I

think it costs $1,000, which is exactly what I’ve got to spend. Then I

discover it’s on sale for $900. Should I buy two? Three? Should I take

the hundred bucks I saved and put it toward more TVs? I suspect Mr.

Caplan’s “just relax” child-rearing advice amounts to something in the

neighborhood of a hundred bucks off a thousand-buck TV. It’s a good

deal, but not nearly good enough to get you to buy more TVs, or kids,

than you thought you wanted.

My graphical representation of Will’s words:

Will’s story has to be far more common than Laura’s. He’s right to point out that kids are a step good; the straight line in my first graph is a simplification. Nevertheless, there’s every reason to think that, on average, demand for step goods remains sensitive to price. As I explain:

Kids, like TVs, come in whole numbers. You can’t have 1.3 kids or

2.7 TVs. For such goods, changing prices often fail to change an individual’s behavior. But changing prices can still have a large effect on average behavior. When stores cut the price of HDTVs by 10%, they sell a lot more. That’s why they have sales.Similarly: If 10% of the people who bought my arguments decided to

have one extra child, I’d call that a big effect – even though 90% left

their family size unchanged.

Graphically, I’m saying that even if most demand curves look like the one above, there are still plenty that look like this:

READER COMMENTS

Tracy W

Apr 14 2011 at 2:04pm

I adore your graphs. And your last paragraph.

Joshua Gans

Apr 14 2011 at 2:13pm

I don’t think Carroll’s demand necessarily looked like that. I think she may have a normal demand curve but a very high fixed cost of that first child.

So her supply curve lies above her demand curve.

You really need to draw some supply curves in here.

James SH

Apr 14 2011 at 2:40pm

Prof. Caplan, this must be one of the best implementations of economic thought I have ever seen (and this is coming from someone with a high opinion of economic thought).

Also, as a side note, those graphs look very much like the demand side of capital budgeting in corporate finance, as, I suppose, would be expected. (e.g. page 7 at http://academic.cengage.com/resource_uploads/downloads/0324594690_163042.pdf)

dullgeek

Apr 14 2011 at 3:08pm

Your book arrived in the mail from amazon yesterday, and I thought that the vertical demand curve was adequately explained in the first few pages – which is all the further I’ve gotten so far.

Prior to having kids, my desire was 2. My wife’s was 3. We ended up with 4. And if you asked me which one I would give back, you couldn’t have any of them. Which is to say that I thought both my wife & I thought we were in the 2nd demand curve, but turned out to be in the 3rd.

I’m pretty sure that I’m done and that I’m no longer interested in additional kids. OTOH if by some miracle my little swimmers managed to circumvent the vasectomy that I got (twice actually) I’m quite certain that I wouldn’t want to give that one back either. I often wonder about all the children I could absolutely adore that I’m not giving my self the chance to know because I’ve decided to be done. Each of the 4 kids I have is unique and I love them each for who they are. I can’t imagine going back in time and *not* getting the chance to know one of them. But here I am now, back in time from some future state willingly not getting to know some other child of mine that I could know.

Josh W.

Apr 14 2011 at 3:55pm

@Joshua Gans

Why consider a supply curve? What’s the economic interpretation of a supply curve in the graph?

It seems to me that a demand curve alone satisfies the relevant question: “how many kids do you want given the price of kids?”

tms

Apr 14 2011 at 4:27pm

This is a great post. Thank you.

Lumberton

Apr 14 2011 at 10:11pm

I used to worry about all the kids stuck in orphanages around the world. From what I understand from the summary of this book, I should not worry, because they will turn out the same whether anyone adopts them or not. Is that correct?

D

Apr 14 2011 at 10:39pm

Lumberton, not even close.

Tracy W

Apr 15 2011 at 5:12am

Lumberton: I should not worry, because they will turn out the same whether anyone adopts them or not. Is that correct?

It’s quite possible that children need parents, as part of normal development, as the brain programmes itself as it grows up. What the adoption studies and the like indicate is that the exact nature of the parents doesn’t matter that much.

Consider that studies have shown that mice raised in a very non-stimulating visual environment have difficulty seeing, in the sense of understanding the world visually. Mice raised in an environment approximating the visual complexity they’d see naturally were much better at seeing. But mice raised in a specially enriched visual environment didn’t do any better at seeing than the ones engaged in a normal environment for that species.

That, and, just because parents don’t have much influence on their children’s adult personalities, doesn’t mean that what they do doesn’t matter now. A parent can make a child really miserable, and that’s bad in and of itself, even if it has no bad long-run effects. And, as Judith Harris points out, how you treat your kids may not affect their relationships as adults with other people, but it may well affect their adult relations with you. In bumper sticker terms “Be nice to your kids, they’ll chose your nursing home.” To bring this back to orphanages, kids can be miserable in those places, and that matters in and of itself.

Joshua Gans

Apr 15 2011 at 7:16am

@Josh W

No it doesn’t. Bryan’s claim was that Carroll had an unusual demand curve. Put in an appropriate supply curve and you can see that claim is unsubstantiated.

Anyway, he has a supply curve in there anyway, it is what determines the points on the demand curve. This is Econ 101 stuff.

Biomed Tim

Apr 15 2011 at 9:19am

@Joshua Gans,

I have a hard time seeing what the supply curve would look like. Who would be the supplier anyway? (i.e. if I demand more kids, I am the one that has to supply it.)

Josh W.

Apr 15 2011 at 11:06am

@Joshua Gans

You still haven’t explained the common sense explanation of what a supply curve is in the picture. Supply and demand curves *are* basic Econ 101 which is why I am surprised you keep making the claim that Bryan’s graph is incomplete without giving any kind of support.

“The demand curve represents how many kids you want, given the price of kids.”

Give me the analogous sentence for the supply curve.

Vince Skolny

Apr 15 2011 at 12:11pm

@Biomed Tim – It’s vertical integration :p

Tracy W

Apr 15 2011 at 12:26pm

Biomed Tim, unless you’re after clones, and you’re female so you can incubate your clone yourself, it takes two people to have kids.

Josh W: “The demand curve represents how many kids you want, given the price of kids.”

And the supply curve represents “how many kids you can supply, given the price of producing babies in the first place.”

Getting pregnant and then getting through to a healthy birth is:

a) not always technically possible

b) sometimes very expensive in financial terms (eg if it requires IVF)

c) often expensive in non-financial terms (eg bad morning sickness, one of my friends had to give up working on her PhD for about 8 months because of about 8 months of full-on vomiting)

d) risky (you might go through 12 weeks of morning sickness and then have a miscarriage, and this might happen multiple times).

And the strain and risk of miscarriage gets worse, apparently, as the parents gets older. Since each pregnancy takes time, and thus for each subsequent potential pregnancy, the woman is a bit older, a supply curve of children will be rising for any individual woman who doesn’t have a completely vertical one.

Vince Skolny

Apr 15 2011 at 12:28pm

I don’t think the root of Byran’s objectors’ arguments are so much in economics as in sensibilities– particularly, theirs being offended at what feels like the “commoditization of children” in Bryan’s book.

It’s the same sort of thing that leads Tom Palmer to deny that all human action is an effort maximize our own utility and to object that not all relations among humans can be reduced to market relations.*

His loaded language aside, of course they can. It’s that beauty of economics which “allows you to give advice and respect pluralism at the same time.”

*I’m referencing Palmer’s words in his essay at the end of Selected Works of Frederic Bastiat published by Students for Liberty as The Economics of Freedom: What Your Professors Won’t Tell You, p 82-83.

Vince Skolny

Apr 15 2011 at 12:35pm

@Tracy W – Those are good points on the costs of pregnancy, particularly that the potential costs tend to rise with age.

We can also assume that (because child production really is rather vertically integrated market, assuming a fertile male-female couple) demand for children will decrease through life because of negative expectations and preferences associated with pregnancy.

Josh W.

Apr 15 2011 at 1:33pm

@Tracy W.

I think what you are describing is information contained within the female’s demand curve. Notice that as the price gets more expensive, she “supplies” less babies. That means she wants less as babies impose more costs on her and the result is a downward sloping (demand) curve.

I would be convinced there’s a relevant supply curve if someone drew a picture with an individual’s supply and demand curve that made sense.

Lorna Hamilton

Apr 15 2011 at 4:59pm

You have to consider that Laura Carroll is actually far less ‘atypical’ than you think.

The true number of people who do not want any children will only be revealed when society changes and stops pressurising people to have them (or fear being considered weird and outcast from some aspects of society). I know many, many people who do not want any children. That doesn’t concern me. What does concern me is I know even more people who had children because they were conditioned from birth that it is just what you do! With hindsight they wish they had stood their ground as they always knew they didn’t want children.

Low estimates for the number of people that don’t want children are around 1 in 10, high estimates are as high as 1 in 5. That means that childfree people are far from atypical. I’d be happy to wager that more people want NO children than want 3 or more!

You are making your assumption of Laura being ‘atypical’ in a society that does not currently allow people to speak out freely and admit to not wanting children. In the same way the official numbers of homosexuals rose as homosexuals felt it safer to reveal their true sexuality, so the number of childfree people will rise once society stops being so pathetic towards people who don’t want to have any children.

Lumberton

Apr 15 2011 at 5:13pm

@tracy w – thanks for the thoughtful response. If I understand correctly, there are three main points:

1) There is some minimal effort required so that your child has a chance to function normally, physiologically, emotionally, and socially. This level of effort is pretty small, but not zero. (I wonder what the threshold is, actually?)

2) Parental effort does have a positive causal effect on the love that children show parents in later life – I wonder what the curve looks like for that.

3) There is negative utility associated with misery in childhood that is worth weighting in its own right.

Do I have it? Anyone care to sketch out the curves for 1) and 2)?

Tracy W

Apr 16 2011 at 11:43am

@Vince Skolny: we could indeed assume that demand for children will decrease through life. As the veteran of numerous physics questions that included the phrase “assume no friction” I am well aware of my ability to assume things regardless of what reality tells me. But with the rising age of average first pregnancy, I’m inclined to think in reality that for many women, the desire for children has a more complicated relationship with age.

@Josh W: No, I’m describing supply curves. A woman might have a very high demand for children, but be unable to supply any, or have a very low demand for children and yet no problems with supply (see the movie Juno for both cases).

I agree that a woman may well want less babies as the price gets more expensive. What the supply curve implies that, as the gains from having babies goes up, a woman may well both be able to and chose to supply more. For example, some women become surrogate mothers.

What the costs of pregnancy imply is that the marginal cost of baby production rises with each pregnancy.

@Lumberton: I wouldn’t describe the effort involved in say, feeding a new born baby, to be pretty small. The studies Bryan is drawing on only look at what happens amongst parents who are already willing to put in the effort in necessary for such a small helpless creature to survive and grow in the first place.

I also am not sure if parental effort, per se, has a positive causal effect on love that children show for parents later in life, at some times quite possibly backing off could have a positive causal effect. And I don’t know if your definition of “effort” includes doing things that both the parent and the child enjoy for their own sake.

I agree with your point 3.

Lumberton

Apr 19 2011 at 9:52am

@Tracy W – I agree that the effort involved in feeding a baby is not small. So it looks like there is a high fixed cost to providing basic case for a baby, with maybe low marginal returns to extra effort beyond that. So the curve is vertical (or horizontal, depending how you look at it) initially to some point, and then flattens dramatically. So equilibrium (and impact of Bryan’s argument on optimal # of kids) would depend whether the curves intersected at the vertical or sloped part. Can’t draw those curves in the comments!

Comments are closed.