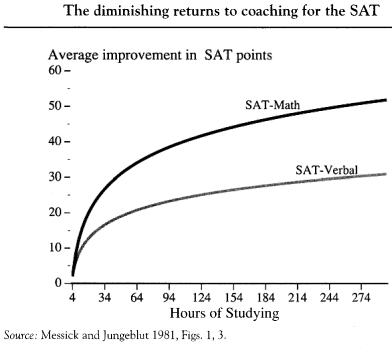

SAT preparation classes don’t work wonders, but they do work. Herrnstein and Murray have a nice graph in The Bell Curve:

This raises a deeper question. Suppose a randomized controlled experiment proved that SAT prep classes noticeably raised your lifetime income. Since employers are extremely unlikely to know that you took an SAT prep class, you can’t just say, “SAT classes send a good signal to employers.” So what’s the right story?

A few possibilities:

1. SAT classes really do permanently raise your cognitive ability, tons of other evidence notwithstanding.

2. SAT classes permanently improve your non-cognitive ability – a.k.a. “character.”

3. SAT classes get you into a better college, which in turn sends a good signal to employers.

Perhaps my personal experience is atypical, but it is extreme: Everyone I’ve ever talked to about SAT preparation believes #3. It’s a simple story, it makes sense, and it’s true to life.

My claim: Economists should take this SAT preparation example to heart. If the labor market really rewards preschool, summer enrichment, or small classes, that hardly proves that a little extra education permanently improve students’ minds or souls. There is a plausible, depressing alternative explanation. Namely: extra education helps students get over the next educational hurdle they’re going to face. Once they get over that hurdle, they reap handsome rewards – even if they’re only slightly more productive than peers who didn’t make the cut. The educational innovations that social scientists keep looking for may, like SAT preparation classes, turn out to be nothing more than rent-seeking.

READER COMMENTS

Mike

Jun 5 2012 at 3:38am

I know it is only one example, but my son raised his SAT score just shy of 500 points on a 2400 point scale. Others I know also raised their scores significantly. So I am skeptical of the study that is cited.

Steve Sailer

Jun 5 2012 at 3:50am

Asians are largely convinced that years of test prep are a good investment for their children. I’m not so sure they are wrong.

Brian

Jun 5 2012 at 4:20am

Let’s send the kids to a Montessori pre-school/kindergarten, I said to the wife.

But it’s not shown to have any positive effect on educational outcomes, she said, and there have been lots of studies.

I don’t care about measured educational outcomes or measured life outcomes, I said, I want them to know from the beginning what it is to reach out and learn something for its own sake and to learn independently. It isn’t going to help with the kind of rent-seeking credential that gets you rich, but It’s good for the soul.

—

As I am often reminded by Bryan’s studies of school credentials, you should never let your schooling get in the way of your education.

Michael Hamilton

Jun 5 2012 at 6:44am

I taught these classes to pay the bills when I was in college. Almost every student improved his score by 250 points. Maybe 5% did so by 500 points.

The SAT has high returns to studying, in my experience. I had a sample size of about 200, though it skewed toward high income.

NB: the results in those two studies aren’t consistent because the scale and composition of the test changed dramatically between the early nineties and 2009.

J Storrs Hall

Jun 5 2012 at 8:13am

Here’s a model for you: Imagine we were all going to spend our lives playing tennis. There are a host of different leagues, paying different amounts, and which league we wound up in was determined by competitions at the ages of 18 and 21. There is publicly-provided tennis instruction.

Someone offers special classes in playing tie-breaks. These are differently-scored games that are only played in high-stress situations (when the normal scoring has resulted in a tie).

It’s clear that extra tie-break training can lower your nervousness factor and give you an edge in those crucial situations. At the end of your life, you’ll have played enough that you’ll be as familiar with tie-breaks without the class as you would have been with it, but the time it makes the most difference is in those crucial early tournaments.

You could say the same about tennis in general — if you’ve spent your whole life playing it, you probably know as much by experience as you would ever have learned in a tennis school. But you would have learned it later, and there may well be many bad habits or poorly formed strokes you might not have formed with early instruction.

Furthermore, even though tennis is nominally a zero-sum game, the actual enjoyment you get from it is distinctly not. A game well-played on both sides is much better, for the players and for spectators, than a poorly played one characterized by mistakes instead of brilliant play — even if exactly the same people win.

Zubon

Jun 5 2012 at 8:57am

While it does not affect the core argument, is this still true for the SAT? The graph says it is from 1981, so the data is presumably older. Test designers have had 30 years to adjust to the test-taking courses. (Ensuing arms race between test designers and course designers? The course designers have stronger incentives, I think.) My prior is that the courses still produce a positive effect, which is all you need for the argument to go forward, but I’m curious about how the data might differ today. The children of the people who provided that data have already taken their SATs.

Zubon

Jun 5 2012 at 9:01am

To note on the 500 point gains: remember regression to the mean. If you take the SAT cold and do worse than expected, you’re a likely candidate for an SAT prep course. Your improvement is the combination of not having a bad day plus experience with the test itself plus the test prep. SAT courses can profitably guarantee that you’ll gain even if they provide no value at all; most people will do better on a second try.

anon

Jun 5 2012 at 9:22am

[Comment removed for supplying false email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment and your comment privileges. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

Chip Smith

Jun 5 2012 at 9:30am

No comment, but I think it’s funny that you are asking readers to speculate on the results of a randomized controlled experiment … that is imaginary. Oh Internet!

Andrew

Jun 5 2012 at 9:33am

How long before schools start asking if students took the prep-course and adjust their scores accordingly?

Joel

Jun 5 2012 at 9:39am

Not that I believe it, but another possible explanation is

4. SAT classes get you into a better college, which gets you a better college education.

In fact, I would be surprised if many anti-signaling-modelists didn’t prefer it to #3.

rpl

Jun 5 2012 at 10:06am

Why is that funny? Any responsible researcher should speculate on the outcome of their experiment before they do it. At the very least, you need to be sure that there is some possible outcome of the experiment that will falsify the theory you are trying to test.

@joel, Does what you said really change anything in Bryan’s argument? In your scenario you still have a positive association between taking test-prep classes and lifetime income, despite the classes having (by your own assumption) no beneficial cognitive effects. That’s all Bryan was really trying to show.

John

Jun 5 2012 at 10:09am

For those who question this study, there are more recent research investigations that have found essentially the same thing; the test prep courses add very little to most students scores in carefully designed studies:

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124278685697537839.html

I know it’s always the case that people want to go to unsystematic anecdotes and memories of people who had massive changes as “evidence,” but the bulk of carefully designed studies would differ with these isolated cases that come to mind. Also, +1 on the regression to the mean and other selection bias factors–those who take prep courses are hardly a random sample of the population.

Ryan Langrill

Jun 5 2012 at 10:43am

What about signaling conscientiousness? I would guess there is some connection between a willingness to work hard and taking an SAT prep class. If the purpose of the SAT were only to measure intelligence, why not just use IQ tests?

JKB

Jun 5 2012 at 11:47am

I saw a TED video of Salman Khan of Khan Academy. He was commenting on the use of his videos in the classroom. Some schools were assigning the instruction by video for homework and then using the classroom for individual help for rough spots.

He observed that normal classroom education is a keep up or get left behind affair. A topic is taught but if you don’t get it in certain amount of time, the curriculum schedule will leave you floundering, especially if it is a topic not required for the next topic. And all students eventually run into a rough spot on some topic, for a variety of reasons. He speculated that those dubbed “gifted” could simply be those kids who’ve avoided their rough spot up until the assessments are made. Once chosen, the resources change for students and the expectations as well.

Could it be, the SAT prep courses simple provide an opportunity to pave over the rough road laid down by classroom instruction? Clear up some things that slipped through the cracks before they become pot holes slowing progression. Couple that with the psychic benefits of “prepping” so as to create calm on test day, you might see the increases reported.

Ted Levy

Jun 5 2012 at 11:50am

” The educational innovations that social scientists keep looking for may, like SAT preparation classes, turn out to be nothing more than rent-seeking.”

Like they say about turtles in another context, it can’t be rent-seeking all the way down…can it?

Finch

Jun 5 2012 at 12:54pm

How about: SAT prep classes indicate you were willing to bet $1000 and a hundred hours or so on your ability to do well in a better college. So people who choose to invest in preparing for the SAT are better prospective employees and students than those who looked at the costs and thought they weren’t worth it. They are revealing their private knowledge.

Sort of like the MBA-as-peacock-plumage theory, but at a smaller scale. I don’t see this as substituting for the other good explanations, but it seems additive.

Chip Smith

Jun 5 2012 at 1:29pm

rpl,

Maybe I shouldn’t have been so glib. Of course I understand that a working hypothesis should inform the way research results are interpreted; I just think the phrasing in this instance is amusing since it requires that we fashion an explanation for a particular set of results that have not really been obtained. Imagine asking James Randi to formulate an interpretation of a “perfectly controlled” — yet imaginary — study that “proved” the reality of telepathy.

In any case, if I were to pretend to interpret the results of such a hypothetical “randomized controlled experiment [proving] that SAT prep classes noticeably raised … lifetime income,” I suppose I would begin by trying to pare out the extent to which gains attributed to test prep might be a proxy measure of the independent role of industriousness (or “character”) on the part of the most successful (therefore more temperamentally invested) test preppers. If you say that’s cheating — that “industriousness” was somehow, unassailably accounted for in the controls — well, then I guess I would be left with no choice but to speculate exclusively on the external signaling and rent-seeking models that Brian has in mind.

The problem is, in the back of my mind, I would still be wondering: What was the je ne sais quoi that made the more successful test preppers more successful test preppers in the first place, and how can we really be sure that quality was vetted in the study design — that it shouldn’t spill over into the real world were myriad human qualities are cumulatively punished rewarded over a lifetime?

John

Jun 5 2012 at 2:24pm

Actually, on a related point, there are quite a few studies by organizational psychologists (e.g., http://psycnet.apa.org/?&fa=main.doiLanding&doi=10.1037/a0013978) showing that SAT scores are substantially related to performance in college and to reduced dropout rates even after taking socioeconomic status of the test taker into account, which I think mutes concern that we’re simply talking about a rent-seeking phenomenon.

Other research in the same field shows that personality (conscientiousness) is not strongly related to test scores either.

Conclusion: I’d say the tests are mostly measuring IQ (correlation between SAT and standardized IQ tests is usually in the mid .80’s) and not much else.

KnowPD

Jun 5 2012 at 3:33pm

I wonder what the graph would look like for GMAT & LSAT and how those would correlate with SAT scores. I also wonder to what extent people enjoy gaming the system (i.e. prefer signaling to “working”) plays a part in the scores.

Nathan Smith

Jun 5 2012 at 10:05pm

I am probably missing something here, but I had the same reaction as Joel. SAT prep classes help you get into a better college, and the better college gives you a better education, i.e., more human capital. A positive result of your imaginary experiment seems no less consistent with the human capital model than the signalling model.

Bryan Willman

Jun 5 2012 at 11:23pm

There can be some very strong “edge” effects.

You did somewhat better on the sat, and got into a better college, which unlike your other choices offers a course of study that you (a) find interesting and (b) leads to good career prospects.

The sat didn’t really prepare you to find joy and fortune as an engineer/programmer/etc., it just got you out of lower state sort of U and into Big Ten Real U where you could have more success.

Sort of like having your life prospects improved when your parents moved to a suburb with a great school district….

Joe Cushing

Jun 6 2012 at 3:45pm

There is probably a difference in the character of a person who will take one of these courses vs the character of a person who does not. Before I took the ACT, I didn’t take a course but I did buy a study book and I studied it. I’m certain that my score was increased by the studying–especially since I took the ACT about a year and a half out of high school.

Comments are closed.