The boss hires his worthless unemployed nephew for a summer job. Does that raise GDP or lower it? To keep things simple think of this as ex nihilo hiring: if not for this hire, the person wouldn’t have been hired otherwise and if the boss doesn’t hire the worthless nephew nobody else is going to get the job.

As we saw

last week, the answer to whether the worthless hire boosts GDP turns on whether the boss works for the government or for the private sector. Let’s take a new look at why.

We usually measure GDP as total spending (by consumers, businesses, governments, foreigners) but it might be clearer if we remember that GDP is also total income: Every dollar spent goes to somebody either as wages or as business profits. Omitting details (e.g., “wages” includes salaries and bonuses, “profits” are often paid out as interest to the bank), we can sum it up this way:

GDP = Wages + Profits

But here’s the thing: Government doesn’t make a profit.

That’s not a punchline: That’s the reason government hiring of the unemployed boosts GDP by definition while private hiring of the unemployed does not. When the private sector boss hires his worthless unemployed nephew, the nation’s total wage bill rises by, say, $100K, but the nation’s total profits also fall by the same $100K: The firm’s decision to hire the worthless worker is the firm’s decision to take an equal cut in profits.

But when the

government hires the same worthless unemployed nephew, the nation’s total wage bill rises by $100K and then…that’s it! Government doesn’t report profits–at least in the GDP figures–so government doesn’t record any – to balance out the +.

A GAO audit might report wasteful hiring but it won’t show up in GDP.

Official GDP statistics assume the value of a government worker is what she costs. Official GDP statistics assume the value of a private worker is what she produces. That’s the reason worthless government workers have a bigger boost to GDP than worthless private workers.

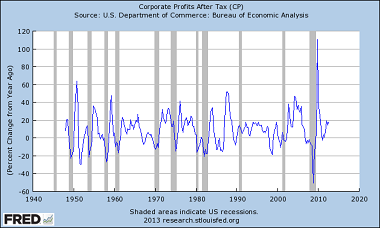

And there’s another lesson to draw from this: If we measured the value of the private sector the same way we measure the value of the public sector–by looking just at wages–then the private sector would look more stable than it currently does. In

the private sector, total wages are vastly more stable over the business cycle than total profits. When the average firm loses sales during a slump profits take the biggest percentage hit, not wages. Profits are—as a matter of arithmetic, leaving causation aside–a volatility multiplier. Image a GDP figure that was missing this:

It would be great to measure how much reported GDP volatility would fall if we calculated the whole thing the same way we calculate the government part of GDP. A task for another day…..

[I thank

Patrick and

Alex for spurring me to think about GDP in income terms.]

READER COMMENTS

Daniel Kuehn

Jan 31 2013 at 9:55am

Doesn’t a government worker get paid out of taxes (from wages and profits) or savings lent to the government (from wages or profits)?

Profit is still important to consider when thinking about government. The lack of profit is bad because there’s no price signal. But it’s good because we don’t think profits are all that great of a signal for public goods anyway. So that’s always worth hiring.

But government wages don’t just materialize out of thin air, right?

Let’s say there was no tax on profits – only a tax on wages. In this sense, wages to a government worker would reduce private profits in the same sense wages to a private worker would, only indirectly in this case.

Daniel Kuehn

Jan 31 2013 at 10:06am

*always worth mentioning.

MG

Jan 31 2013 at 11:58am

The basic definition of economic profits (say period income less period expenses) improves tremendously when both income and expenses are adjusted in ways that make them, essentially, consistent with the contemporaneous contribution to the growth in business’ net equity. Thats why you have depreciation charges, amortization of capital expenses, adjustment for non-recurring one-off charges, etc. These adjustments help reconcile the past, the present, and the future, and differentiate between activity and accomplishment. The day when government funding incorporates a significant element of equity financing, the more some will find all the inadequacies of GDP more than just amusing, and will demand signals that would better keep policy makers from hiding behind the cover of “is government, is valuable”. The issuance of a National Balance Sheet would be a good start. (Funny, it occurs to me that we as taxpayers ARE the biggest “equity” holders — certainly, we are the first in line on the cash call — and we don’t demand any of this. Of course, the way voting rights and “equity” are allocated in a demoracy suggests an answer why this happens.

Phil

Jan 31 2013 at 4:19pm

The corollary, then, is that any government employee who adds value (produces utility that is valued in excess of their cost) results in an understatement of GDP?

blink

Jan 31 2013 at 5:22pm

As with the previous post, this one makes an important point. But “image a GDP figure…”? It feels like you are leaving out the punch-line! If a figure is not readily available, some discussion of the relative magnitude of wages vs. profits would help.

E. Barandiaran

Jan 31 2013 at 6:27pm

Garett,

You may want to comment on this controversy

http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2013/01/31/the-rise-and-fall-of-government-spending/

Hope you have a good assistant to explain the different definitions of government spending involved in the controversy.

Conor

Feb 6 2013 at 4:37pm

I have a question similar to Mr. Kuehn’s. Are taxes considered the same as other spending, or does GDP fall by the amount taxed and rise by the amount paid out to govt. workers

If I make $100,000 and am taxed $20,000, which is spent hiring a govt. employee, is GDP $100,000 or $120,000.

Surprisingly difficult answer to find out online and I don’t have a textbook on hand.

Comments are closed.