Tom Brown sent me to an Austrian critique of monetary stimulus (in this case negative interest on reserves):

Negative deposit rates” means that the banks will charge the customer for saving money and placing it in the bank. According to Keynesian theory (if there really is such a thing) government needs to spur “aggregate demand” in order to stimulate the economy to increased production. Keynes had no respect for savings…only spending. He called the consequences of savings to be a “paradox of thrift” in that if we all save instead of spend, then the economy will go into a death spiral. He was completely ignorant of capital theory, which explains that REAL capital, not paper money capital, comes from deferring spending ON CONSUMER GOODS in order to increase spending ON CAPITAL GOODS. The money that we save is not destroyed. It goes into the lendable funds market to finance long term capital investment that will pay future dividends, both literally and figuratively, ensuring MORE goods in the future.

He’s right about 2 things. The paradox of thrift is a silly concept. And it is usually the case that monetary stimulus will discourage saving and hurt the economy. This is because monetary stimulus cannot push growth past the natural rate, based on population growth, technology, government institutions, etc. But it can raise the rate of nominal GDP growth. This raises the nominal returns to capital without raising the real returns. Even worse, nominal returns are taxed, so the real tax rate on capital rises with faster NGDP growth and this discourages capital formation, slowing economic growth.

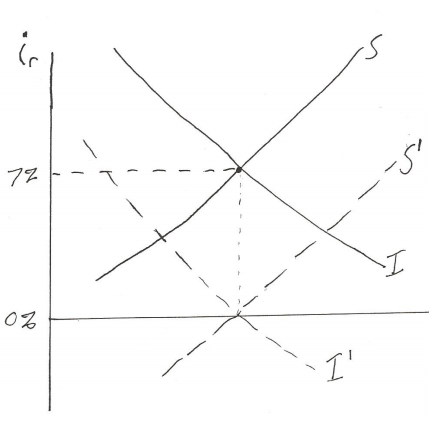

Things are very different, however, when the monetary stimulus is making up for recent monetary tightness, which drove real output below potential. In that case, monetary stimulus can boost real output because nominal wages are sticky, or slow to adjust. And here’s what is surprising, this sort of growth will lead to more saving, not less. The easiest way to see this is with a closed economy model, or a model of the global economy where all the major central banks are doing stimulus.

Recall that, by definition, saving equals investment. Also recall that the share of GDP spent on investment goods is procyclical. That means investment spending rises faster than consumption during booms and falls faster than consumption during recessions. During a recession monetary stimulus raises real economic growth, which causes investment to rise faster than consumption. Since saving equals investment, saving also rises faster than consumption. Monetary stimulus actually causes people to save a larger share of their income.

Keynesians try to explain this result by distinguishing between planned and actual saving, but that explanation is not satisfactory. If the public is rational they will fully understand what is going on. The monetary stimulus will cause them to plan to save more, and to actually save more. There are two better explanations:

1. The monetary stimulus leads to faster expected growth in income, and the marginal propensity to save out of an extra dollar is greater than the average propensity to save.

2. The monetary stimulus may increase the expected real rate of return from saving. This will show up in higher long term expected yields from stock and bond purchases. This odd result (an upward sloping IS curve) does seem to occur on occasion, but is hard to predict.

One final point. Real interest rates on long term Treasuries have been falling for more than 30 years, from over 7% to near zero. The causes are poorly understood. Here are some possibilities:

1. Increasingly easy money.

2. Increasingly tight money.

3. Demographics and technological change.

4. Piketty is wrong about everything (just kidding.)

The first explanation is very doubtful; NGDP growth and inflation have been slowing for more than 30 years. There’s no model that predicts increasingly easy money would produce that result.

The second explanation is slightly more plausible, but only for the period since 2008. Tight money in 2008 caused a deep recession, which lowered real returns on capital. But this doesn’t explain the 30 year downtrend.

The third explanation is the most plausible. Because quantities of saving and investment (as a share of GDP) haven’t changed dramatically, it seems the global supply of saving must have shifted right, while global investment demand shifted left. Thus rates fell sharply with little change in the actual quantity of global saving and investment as a share of GDP. Possible explanations:

1. Higher saving rates due to demographics, particularly in Asia. Slowing population growth.

2. The investments of the 21st century (such as Facebook) require less capital than typical 20th century projects, such as interstate highway system and automobile factories.

3. An increasing gap between the risk-free rate and the average return on capital.

4. ?????

READER COMMENTS

Steve J

May 26 2014 at 10:57pm

Is the paradox of thrift silly when the money supply is not increasing?

dannyb2b

May 27 2014 at 12:57am

“Recall that, by definition, saving equals investment.”

A definition that many don’t agree with it seems.

Enial Cattesi

May 27 2014 at 3:52am

I have a problem with:

1. The title, “The goal of monetary stimulus is to boost saving.” But “they” say it is to increase aggregate demand. This kind of thinking always reminds me of the president of the German Central Bank during the Weimar hyperinflation: it will end when they will have better printers.

2.

Actually they require a lot more capital, but maybe less investment funds. Maybe. It is very hard to compare the today’s business environment with the one from 100 years ago.

bluegreen

May 27 2014 at 5:24am

Which part of the paradox of thrift is silly: the idea that aggregate spending equals aggregate income or the idea that cutting aggregate spending (through increased savings) will lower aggregate income, thereby lowering the amount available to be saved?

Bill woolsey

May 27 2014 at 7:33am

The second part.

Identifying consumption and spending is the error. Investment is also spending. It is spending on capital goods.

The paradox of thrift is an confused and awkward way of describing the fundamental proposition of monetary theory. If an individual demands more money, then reduced spending and sales of assets results in an increase in the amount of money the individual holds. The individual’s supply rises to meet the demand.

But for the economy as a whole, given the money stock, an the efforts to accumulate larger money holdings results in changes in interest rates, real income or the price level such that the demand to hold money reverts to its initial level.

An increase in the quantity of money, or else lower interest rates paid on money, will allow the demand for money to equal the quantity of money without disruptive effects on (other) interest rates, real output, or the price level.

Scott Sumner

May 27 2014 at 8:58am

Steve, No, it’s not silly in that case.

Danny, That’s the textbook definition. Of course people are free to define words as they choose, but we need some sort of consensus on definitions in order to have an intelligent discussion.

Enial, Yes, perhaps the title is misleading. The goal is to boost AD, as you say, and the expectation is that this boost to AD will also cause S and I to increase.

bluegreen, It’s certainly a truism that gross income and production are identical. The second claim is more dubious. It’s not at all clear that more saving will lead to less spending. It might lead to more spending on investment goods.

Also, check out the next comment by Bill.

vikingvista

May 27 2014 at 12:58pm

Is my putting cash in my cookie jar not saving? How is it investment? Since I am not trading away that cash, how is it spending of any sort?

‘Savings equals investment’ may be a reasonable assumption for a macroeconomic model of a modern economy, but strictly speaking, doesn’t saving equal deferred consumption?

Hunter

May 27 2014 at 2:13pm

Question: Can’t savings be considered inventory + investment.

AbsoluteZero

May 27 2014 at 2:24pm

@vikingvista,

Cash is an asset class. Holding cash is an investment.

You can spend cash and buy cash, in another currency. Assume your cash is in USD. You can spend that and buy, say, RMB. You can keep the RMB bills in your cookie jar. You still hold cash, but it is definitely an investment.

Scott Sumner

May 27 2014 at 9:36pm

Vikingvista, Saving doesn’t equal investment at the individual level, only at the aggregate level. If you increase your holding of cash by one dollar, someone else reduces their holding by one dollar.

Hunter, Increases in inventory are treated as part of investment.

vikingvista

May 28 2014 at 4:22am

AbsoluteZero,

Investment is a kind of spending–spending for future consumption. Spending is a kind of trade–trading away money for something. If there is no trade, then there is no spending, and no investment. If I trade away a service or non-money asset for money, and then hold the money, I have spent nothing. Having spent nothing, I have invested nothing.

However, to your point, if I spent my money on some other currency, that would be an investment. However, that was not my original point.

vikingvista

May 28 2014 at 4:46am

Prof. Sumner,

“If you increase your holding of cash by one dollar, someone else reduces their holding by one dollar.”

Assuming conditions for which that is true, it still sounds odd to refer to holding a dollar as “investment spending”.

It seems that I don’t grasp the way economists use the words “spending”, “saving”, and/or “investing”. In my mind there are 3 mutually exclusive categories describing what you can do with your money:

(1) consumption spending,

(2) investment spending,

(3) non-spending.

(1) & (2) alone are spending.

(2) & (3) alone are saving.

Greg G

May 28 2014 at 7:59am

vikingvista

Your formation of the question is admirably lucid and I am interested to hear Professor Sumner’s answer.

But doesn’t your formulation of the question make quite obvious that, if too many people choose your non spending cookie jar option, that will result in a classic Keynesian liquidity trap and shortage of aggregate demand?

Lauren

May 28 2014 at 8:26am

Two tidbits:

1. I think the phrase “by definition” in the sentence, “Recall that, by definition, saving equals investment,” caused some confusion. Savings and investment are not equal by definition, but rather as a conclusion–albeit a very simple conclusion–necessitated by the fact that in an economy as a whole, there is a budget constraint. If you fully account for everything, then as a mere matter of accounting, every dollar (or good) saved throughout the economy has to be a dollar (or good) spent on something that is definitionally investment (as opposed to the only other option–consumption).

2. There are a couple of podcast episodes that discuss the paradox of thrift over on EconTalk. It can be surprisingly confusing, so it might help to hear it from a Keynesian: Fazzari on Keynesian Economics. It’s a bit self-serving of me, but among the over 100 comments, I might also point out my comment discussing how and why the paradox of thrift doesn’t occur in the classical model of the economy. Also helpful on the paradox of thrift is the episode Reis on Keynes, Macroeconomics, and Monetary Policy.

Greg G

May 28 2014 at 9:11am

Lauren

Thanks. Your framing of the issue in your comment on the Fazzari podcast was quite helpful.

I think it is important to point out that even though savings (invested or not) is intended for future consumption, there is no guarantee that intended future consumption will actually be realized.

During depressions the whole economy can shrink and savings can be destroyed without necessarily being spent on anything or invested in anything. Now if that savings was literally in the form of cash in a cookie jar it would appreciate in value during a deflationary depression. In that scenario the cookie jar might be seen as a wise investment choice as the real purchasing value of that money increased.

But in real life most savings is deposited in a various financial institutions. If a lot of them go bankrupt at once a lot of savings can be vaporized and never realized as deferred spending or investment at all.

vikingvista

May 28 2014 at 1:37pm

Greg G,

My (erroneous) semantics don’t in themselves preclude a liquidity trap, but they certainly don’t make one necessary or at all likely, even if large numbers of people hoard cash.

That requires further *economic* assumptions (not semantics) that I find unbelievable for those who think that there are forms of recessions that are permanent without central planning intervention, and dubious for those who think that such recessions are best remedied by central planning measures.

First, but not exclusively, because even in recessions people hoard very little cash–instead, people spend it on debt investments such as bank deposits. Even without the modern central planning diversion of bank reserves into treasuries and interest-bearing central bank deposits, increasing commercial bank liquidity reduces the risk that banks make when investing in a recessionary economy–a necessary and positive market response to such economic conditions.

But also because the liquidity trap theorists ignore (and run roughshod over with fiscal measures) the careful dispersed man-on-the-ground resource reallocation occurring during the recession that sets the seeds for a sustainable recovery. It is a mistake to think that an oversupply of or reduced demand for loanable funds means that there is no significant and expanding (even if presently small) amount of profitable investment occurring.

Scott Sumner

May 28 2014 at 7:51pm

Everyone, The paradox of thrift does not say that money saved somehow fails to lead to investment. Rather it says that intentions to save might not be realized. Actual saving must equal actual investment for the same reason that quantity bought equals quantity sold. They are two sides of the same coin.

Although quantity bought must equal quantity sold at the aggregate level, that’s not true at the individual level. Similarly, at the individual level one might save without investing, say by putting money in a piggy bank. But in that case someone else is investing without saving. In the aggregate they are equal, because saving is defined as income minus consumption, and investment is defined as income minus consumption.

Vikingvista, The term “spending” ought to be avoided, as it has multiple meanings. To economists it means something like aggregate demand. To average people it means something like income minus consumption and also direct investments (1 and 2 on your list.) But that’s not a useful category. It’s not clear why average people consider purchase of a home to be “spending” but purchase of common stock to be non-spending.

Scott Sumner

May 28 2014 at 7:55pm

Oops, in my previous comment I meant average people consider spending to be consumption plus direct investments. They consider saving to be income minus spending.

AbsoluteZero

May 28 2014 at 9:34pm

Scott, thanks for the comment and clarification. I ask because in finance holding cash, in whatever form, is considered investment. Now I think I know why the term “spending” is rarely if ever used in finance, and why it’s always an investment portfolio, never a savings portfolio.

One way to think about it is that everything is a bet, including doing nothing. This conflicts with many people’s intuitive understanding of some terms (and it appears to conflict with usage in economics as well). Imagine a decision loop. It doesn’t matter whether the period is one millisecond or one year. Given available information, one decides on what to hold until the next decision point. Often the decision is to continue to hold exactly the same things, in which case there is no transaction. Sometimes what one holds is just cash. But it’s still a bet. In this world there is no such thing as “spending”. We’re just continuously converting something to something else.

This has implications that are perhaps not obvious. For example, what most people think of as insider trading is really only half of it. If one had intended to go long or short, but with insider information decided to do nothing, that’s actually insider trading. This is impossible to detect even with perfect monitoring, as there was no transaction, but in a way there was a “trade”, which was to continue to hold.

Mark V Anderson

May 28 2014 at 9:50pm

If lots of folks put money in cookie jars instead of in the bank, which lends money out, then there is less cash to lend out. But the resources available are the same, because money is just something that facilitates trade and indicates debt from one person to another. So what should happen is that all this cash out of circulation should cause deflation, which results in the same amount of spending as before. Of course it is true that this doesn’t account for sticky prices.

On the other hand, if true resources are held back, I think that would hurt the (short-term) economy. If factories are moth-balled or oil is warehoused instead of used, that is a real drop in consumption. Of course there are times when withholding these assets from production does help the economy in the long-term, if they are in surplus, and will be more useful in the future. But I think it will always hurt short-term GDP.

vikingvista

May 28 2014 at 10:12pm

“investing without saving”

I appreciate your responses. I agree that “spending” is ambiguous, unless clearly defined as “trading away money”. I also agree with what you say “average people” think “saving” means, but my belief is that they are simply wrong, just as average people are wrong about so many things in economics.

But it seems I too am wrong, as your phrase above is to me a semantic impossibility.

I think now that I may need more remedial help on economics jargon than an anonymous blog poster should expect.

vikingvista

May 28 2014 at 11:46pm

Prof. Sumner,

“investing without saving”

What would be an example of this?

vikingvista

May 29 2014 at 12:14am

AbsoluteZero,

One could avoid these difficulties by not using “spending” but merely talking about decisions of resource use (e.g. deciding to hold AT&T, or deciding to sell RMB).

However, the topic is *monetary* theory, and so everything is from the perspective of money. In particular, in reference to the keynesian circular flow models, we are talking about money transactions (the movement of money), which I think can be unequivocally referred to as “spending”, with the only transactions that are even counted as significant being those making use of the common medium. And Prof. Sumner in his original post and first response above instinctively used “spending” (in particular “investment spending”) clearly as a monetary, rather than a more general resource allocation, phenomenon.

So in the context of monetary theory, what do “investing” and “spending” mean? Something to do with moving money, no? Money moves into my hands as income, but if the money doesn’t move again, how is that investment spending? At what point do we say the investment spending is occurring–simultaneously with the income? My decision not to immediately spend that income on consumption (or anything else) is counted as a decision to spend that income on investments?

Oh well, at some point, I suppose I just need to accept the terms of art for aggregates, rather than trying to make sense of it from a micro level.

AbsoluteZero

May 29 2014 at 1:35am

vikingvista,

First, thanks for your comment.

If you keep the money you were paid, it just increases the cash portion of your portfolio. And yes, it is the moment you decide to keep the money. From that point on until the next decision point, you have that much extra cash in your portfolio. Everything is a bet. One is always going long and/or short something. The moment you decide to keep the money is the moment you decide to go long that much cash.

vikingvista

May 29 2014 at 4:05am

AbsoluteZero,

So then “income” = “investment spending”. That certainly sounds peculiar. One has to accept that in the context in which you speak, both investment and spending can be inactions. That is fine, as the concepts are sound and one can give sound concepts any linguistic label one likes. But this choice of labels guarantees persistent confusion.

The difference between you and I is semantics and focus (I see a useful distinction in monetary economics between an individual trading away his money and not doing so, for the purpose of future consumption, while you find lumping them together suits your purposes.) Prof. Sumner OTOH says the individual distinctions I speak of perfectly cancel in the aggregate. I just don’t yet see the perfectly part of it.

The risk argument, I don’t follow. There is a risk of any future outcome regardless of one’s current action or inaction.

bluegreen

May 29 2014 at 6:30am

[Comment removed for supplying false email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring your comment. We’d be happy to publish your comment. A valid email address is nevertheless required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

Greg G

May 29 2014 at 7:37am

vikingvista

I’m not 100% sure I understand what Professor Sumner is saying but I think that “investing without saving” describes the “paradox of thrift.

So then let’s say I start this next year on Jan.1 with 100K in my retirement account which is all invested in common stock. I call this my “savings.” Next let’s assume I save half my paycheck each week and use it to buy additional stock for my retirement account.

If enough other people sell stock and put the proceeds in their cookie jars then stock market values may fall so much during the year that I find at the end of the year I have less “savings” in this retirement account than I started with even though I have done nothing myself but add to it.

Of course today the “cookie jar” is a bank account that pays a zero or negative real interest rate on money the bank holds but does not lend.

The money I paid for my additional stock purchases during the year equals what the sellers of that stock got for selling it. But when they take those proceeds and put them in that cookie jar/bank account they are “saving without investing” so to speak.

Greg G

May 29 2014 at 8:06am

vikingvista

You say, “It is a mistake to think that an oversupply of or reduced demand for loanable funds means that there is no significant and expanding (even if presently small) amount of profitable investment occurring.”

OK fair enough but I’m not sure that anyone actually thinks that. The debate is over what policies lead to an optimally fast economic recovery. Liquidity trap theorists may or may not be wrong but I don’t see where what you have written above is part of their theory.

AbsoluteZero

May 29 2014 at 6:31pm

vikingvista,

I think the LHS should be “income minus consumption”. And I think we should avoid the problematic word “spending”. Then it becomes “income minus consumption = investment”. I think that sounds far less peculiar. I believe we are all comfortable with “income minus consumption = savings”. I was just pointing out that, in a portfolio management or asset allocation context, savings is also investment.

I’m not sure what you mean by the risk argument.

vikingvista

May 30 2014 at 12:27am

“I think the LHS should be “income minus consumption”.”

In the example being discussed, one describing the holding of money, there is no consumption, that is why “income” = “investment spending”. We are all agreed on what the longstanding textbook definitions are, whether or not we agree on what they should be.

“I think we should avoid the problematic word “spending”.”

I’m not disregarding this rectifying point. I just don’t think it can be avoided. Sumner didn’t avoid it when making this post or in following up, and economists like him will continue to use it. “Spending” is here to stay. Is that a mistake, or is there some economic significance in discriminating between trading away money, and not doing so? I think it depends on the context. In your context about the *state* of resources, no there isn’t. But if *dynamics* (movement of money, positive human action) are the focus, then language that distinguishes static from dynamic is needed. It is the difference between what is (an investment) and what is being done (investing).

“I’m not sure what you mean by the risk argument.”

…”everything is a bet, including doing nothing”

vikingvista

May 30 2014 at 12:39am

Greg G,

“I think that “investing without saving” describes the “paradox of thrift.”

What you describe above may be what he meant–that the value of someone’s savings is being depleted. But saving is an action, and savings is a thing. In my mind, saving is not the continuous and possibly unchanging state of having savings (although grammatically one could read it that way), but instead saving is an action taken by a person with his property. Saving isn’t a state of existence, but rather a transformation from one state to another.

I suppose either ambiguous interpretation of the language is reasonable, but my interpretation seems straightforward and also in keeping with the atom of economics–the trade (or perhaps, the human action).

vikingvista

May 30 2014 at 12:45am

Greg G,

“The debate is over what policies lead to an optimally fast economic recovery.”

Since I know of few policy makers who advocate laissez faire during recessions, I have to disagree. Actually, it would be surprising if any economic debate ever ended. Even hard sciences are often not that solid.

“Liquidity trap theorists may or may not be wrong but I don’t see where what you have written above is part of their theory.”

I believe Paul Krugman’s articles are available in the NYT archive.

Greg G

May 30 2014 at 7:31am

vikingvista

I liked your reference to “the atom of economics” but probably not for the reason you intended. My understanding (correct me if I am wrong) is that you are an Austrian who thinks that microeconomics is all there is and that the study of macro will confuse more than it clarifies.

So then, the metaphor of the “atom” of economics would imply that there is a need to study “molecules” of economics. Molecules have many emergent properties that will not be revealed by studying atoms. And cells and organisms have further emergent properties that will not be revealed by a study of their building blocks.

When I said “The debate is over what policies lead to an optionally fast economic recovery.” I think you misinterpreted me as using the word “over” in the sense of “has ended.” I meant it in the sense of “is about.”

It is certainly possible that you have read more Krugman than I have. Even so, I have read enough to be surprised that you claim he fails to realize there is a real (but sub-optimal) recovery happening with significant profitable investment occurring. In fact, my understanding is that he sees investors making lots of profit and that is a big part of the inequality debate.

If you can refer me to a specific column (you seem to think there are many) I would be interested to see how you back up what seems to me at this point to be a straw man claim. In the absence of that I don’t plan to search the NYT archive for something I don’t even think is there.

AbsoluteZero

May 30 2014 at 6:39pm

vikingvista,

Actually I have not been trying to argue for any position. I was just trying to point out that, from a certain perspective, and in a certain context, seeing savings as investment not only can make sense, it is in fact the normal for some people in some fields.

When I said “I think we should …”, I was really just referring to the two of us in this conversation. And really I meant more like “I wish we could …”. Of course the term “spending” is here to stay.

As for my comment about everything being a bet, again, it wasn’t an argument, for anything. It’s just a point of view. Choosing to not bet is a bet as that is what one believes is the advantageous thing to do, for the time.

As for the rest of your comment, I actually agree. The thing is, concepts like movement, static and dynamic, and so on, are actually quite interesting. An actual reply would be seriously off-topic, so even if the editors or mods allow it, I don’t think it’s appropriate. But I can give an example and a pointer.

Say a group is responsible for setting a certain number for the company every quarter. It goes from 1 to 10. This number is important for the operation of the company. The group do their work, and come up with a number every three months. One time it was 2. Three months later, it was 2 again. People might say, They decided to not change the number. In a sense that is what the group decided. But in a sense they didn’t decide to not change the number. Their work is not to decide whether the number should change, and by how much. Their work is in come up with the number given all the inputs. And it just so happen that this quarter, the output number is the same as that of the last quarter.

Now more generally, things can be seen as moving or not moving. But this is not the only way to look at a system. I don’t know how familiar you are with computational theory, and in particular a class of models known as cellular automata. A famous one is Game of Life. In these systems people can see what they would call movement, even though there really is no movement. It’s hard to explain and I apologize, but I encourage you to look into it.

Roger McKinney

May 30 2014 at 9:03pm

I don’t see how monetary stimuli can do both. The whole point of the stimulus is to cause price inflation and thereby reduce real, sticky wages. How can people save more when they earn less? Of course, the answer is that there is more going on than just stimulus, wages and saving. People do actually reduce consumption in recessions and save. Sometimes that can appear as if the monetary stimuli caused the savings, but it’s actually hindering saving by reducing wages.

Otherwise, I don’t think an Austrian economist would disagree with your description of how monetary stimuli work. But we would add that the short term benefits don’t outweigh the long term costs in the form of an unsustainable boom followed by a wealth destroying bust.

As for the causes of low interest rates in the US, it’s clearly false that savings outside of the US could cause it. How can Chinese, for example, invest in the US and cause lower rates without having the US dollars to do so? They can’t invest yuan or remnimbi. So how to they get the US dollars without the Fed printing them?

Obviously, the Fed prints more money than Americans want to hold and they spend it on Chinese imports. That gives the Chinese US dollars to invest in the US. So the source of all low interest rates always begin with the Fed. Foreign savings is just one stop the new dollars make before coming home to roost.

Comments are closed.