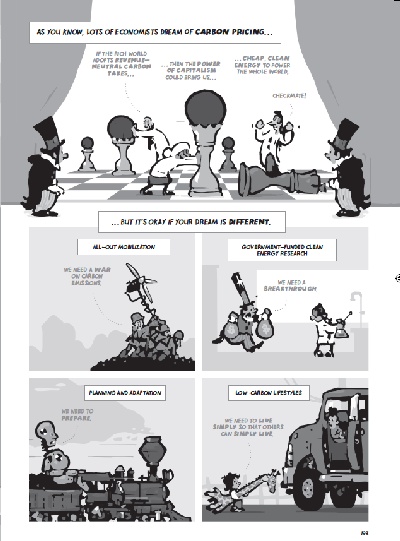

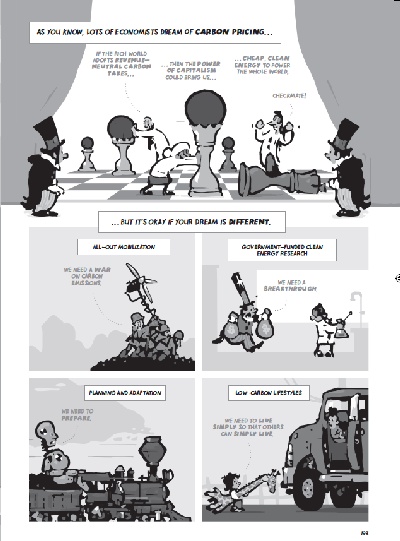

While there’s much to like in Yoram Bauman’s Cartoon Introduction to Climate Change, this page nicely captures my reservations about his approach: He’s tolerant of economically illiterate action, but intolerant of economically literate inaction. (Click to enlarge).

[Excerpted

from The

Cartoon Introduction to Climate Change by Grady Klein and Yoram Bauman,

reprinted with permission from Island Press.]

Read the panels. Instead of pointing out the standard economic (and public choice) arguments against populist approaches like “all-out mobilization,” “government-funded clean energy research,” and “low-carbon lifestyles,” Yoram reassures readers that “It’s okay if your dream is different.”

But the dreams of “wait and see if global warming is really going to be a big deal,” “wait and see if geoengineering can solve global warming for a small fraction of the cost of conventional approaches,” and “wait for developing countries to move along the environmental Kuznets curve” don’t get the same sympathetic hearing. They literally aren’t in the picture. (Some of the the latter arguably overlap with “planning and adaptation,” but I doubt many readers will connect the dots).

What will Yoram’s typical reader take away from his book? Something like: “We definitely have to do something about global warming, and maybe environmental economics can help us get more bang for our buck.” A better takeaway, though, would have been: “Maybe we should do something about global warming, and environmental economics can definitely help us get more bang for our buck if we do.” For now, Yoram’s got a monopoly on the non-fiction climate change/environmental economics graphic novel market. I wish him success, but there’s ample opportunity for an entrant to come along and improve the story.

READER COMMENTS

ThomasH

Jun 6 2014 at 7:34am

The best message would be: We have to do something about climate change, but don’t panic. With good policy, the costs are manageable because they will be more evenly spread throughout the economy instead of falling arbitrarily on certain activities and because they will create incentives for the development of new technologies and the application of old technologies in a way we can’t even imagine.

I think we know what the “wait and see” strategy means: a series of ad hoc policies that have the potential of being very high cost (and over time will become more high cost) and which create vested interests that will be hard to get rid of when we eventually adopt a carbon tax and can even join forces with groups who oppose a carbon tax.

blink

Jun 6 2014 at 3:11pm

You make good points with all of the pages/pictures you excerpt. Still, I think you still own Yoram at least one more example: Something that you learned from the book.

Vangel

Jun 10 2014 at 9:55pm

ThomasH writes:

The best message would be: We have to do something about climate change, but don’t panic. With good policy, the costs are manageable because they will be more evenly spread throughout the economy instead of falling arbitrarily on certain activities and because they will create incentives for the development of new technologies and the application of old technologies in a way we can’t even imagine.

The best message is that we have no idea what is going on and what is cause and what is effect. Yes, the world may be getting warmer if we choose the Little Ice Age as a starting point. But it isn’t warmer if we use the MWP, Holocene Optimum, Roman Warm Period, or possibly even the 1930s as alternate starting points. Not only that but there is no reason to think that warmer means more dangerous. After all, the supposed warming coincided with a huge increase in agricultural yields, overall productivity, and the standard of living for most people on this planet. And doesn’t history tell us that the Medieval Warm Period was a much better time for people than the Little Ice Age that followed?

Another message would be that before we ‘do something’ we may want to identify what the terms mean. What exactly is the average temperature all about? After all, if we look at the actual temperature data for stations with a continuous history of operation we find that for most countries on this planet of ours the highest temperatures recorded took place more than half a century before the present. If higher highs is not what a higher average means why is the number important? It could very well be that the average global temperature is about as meaningful, as one scientist said, as the average global telephone number.

I think that many economists have become so confused by their own methodological issues that they do not see that the alarmists have exactly the same problem. The models do not work because they are based on premises that are faulty and assumptions that are not reflective of the real world. Assuming linearity to make the math work does not yield a good analysis of a complex system like an economy or the climate.

Jeremy

Jun 12 2014 at 5:32pm

I found this to be a cogent dissagregation of the types of geo-engineering we should or should not pursue:

http://carbonremoval.wordpress.com/2014/06/12/is-cdr-geoengineering/

Comments are closed.