Tyler Cowen often has posts entitled “A very good sentence.” Here Tyler dishes up one of his own:

Yes, it is a big mistake to assume Say’s Law always holds but it is an even bigger mistake to think it never holds.

I’d like to discuss the following sentences:

Supply slowdowns are bad for demand, and they likely are bad for credit creation too, which hurts demand further yet.

There is no contradiction in a model where both aggregate demand and aggregate supply curves shift in unfavorable directions! And in the medium run, each of these shifts pushes the other curve around too.

I think this is right, and in the past I’ve discussed how the AS and AD curves are “entangled” in practice. But it’s also important to understand the mechanism(s), because there is nothing “natural” about this entanglement.

Let’s start with the easiest entanglement to explain, the medium term. Suppose NGDP trends upward at 5%/year, with 3% RGDP growth and 2% inflation. Then we are hit by a supply shock that reduces growth to 0% for one year, assuming we stay at full employment. What happens next? If the Fed is targeting NGDP, then inflation probably rises to 5% and real growth falls to zero percent. Employment is roughly unchanged. No impact on demand. But let’s say they are targeting inflation. Then NGDP growth slows sharply. And because nominal hourly wages are sticky, employment also falls sharply. Now RGDP is falling for two reasons, falling productivity (supply shock) and falling employment (due to a demand shock). RGDP turns negative. This isn’t exactly what happened in 2008-09, but it does pick up some of what occurred.

Now let’s move to the very short run. If the central bank is targeting interest rates in the very short run, a supply shock may lead to lower AD. For instance, a sharp rise in the minimum wage or oil prices might depress business investment. This reduces the demand for credit, depressing the Wicksellian equilibrium interest rate. If the central bank is slow to react (keeps targeting interest rates at the same level) then NGDP starts to fall. Thus AS and AD are entangled in both the short and medium run. But how about the long run?

The natural rate hypothesis says that it wouldn’t matter if AS and AD were entangled in the long run, because AD doesn’t matter in the long run. Thus long run stagnation cannot be a demand-side problem. Is this prediction of the standard model correct? The old Keynesians say no, as do new Keynesians who are increasingly drawn to the old Keynesian model (Summers, Krugman, etc.) It mostly hinges on how you feel about money illusion and wage stickiness near the zero level of wage increases. And at an empirical level, it depends what you make of the Japanese experience over the past two decades.

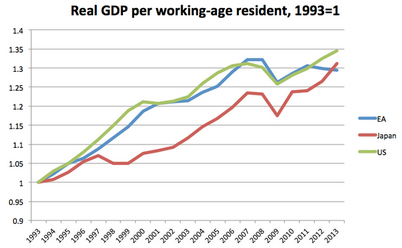

I’m agnostic on this question. Ironically, Krugman just presented some data that seems to slightly undercut his argument. He has a graph that shows the Japanese have not done as bad as people assume over the past few decades, if you adjust for growth in the working age population. First one small quibble with the graph; I’d like to know how many elderly Japanese are working before I assume the working age population is the right figure to use when adjusting GDP. Japan has a lot of old people, and their number is growing really fast. So Japan may have done worse than Krugman indicates.

But let’s put aside that issue, and assume Krugman’s graph is basically correct. When I look at the graph I see a country falling well behind the US for about a decade, then partly catching up. Younger readers should keep in mind that the relative decline in the 1990s was a big shock to most Westerners. As late as 1991 Japan was viewed as a sort of turbo-charged super-economy, with a more efficient economic model than the West. So I think there is at least a pretty strong prima facie case to be made for the claim that it was the sharp slowdown in NGDP growth that triggered the underperformance. But Krugman’s graph indicates that this underperformance lasted for about one decade, not two. This suggests that in the very long run AD shocks might not matter, or (more likely in my view) matter only a very small amount. It’s hard to tell because the baseline (other developed countries) had their own problems more recently.

Returning to Tyler’s great sentence, despite my constant bashing of the ECB, here’s what I would say about Europe:

1. The sharp rise in European unemployment during 2008-09 and 2011-13 was due to tight money that slowed NGDP growth. Note that BOTH slumps immediately followed ECB tightening, by any measure you choose (NGDP, or target short term interest rates.)

2. The enormous difference in the performance of countries like Greece and Italy relative to Germany and Austria is a supply-side story. They face the same monetary policy. And in the long run that divergence may be the biggest story in the eurozone. The rise in unemployment is really important, but the long run failure of certain economic models is really, really important.

So why do I focus so much on monetary policy? Partly because it’s by far the easiest problem to fix, structural reforms are much harder. Note how Abe quickly changed monetary policy in Japan, ending deflation, but wasn’t able to enact structural reforms. And second, it’s my area of expertise; prior to 2008 I had devoted my life to studying issues like the Great Depression, NGDP targeting, and the Japanese liquidity trap. There are lots of $100 bills lying on the sidewalk waiting for the ECB to pick them up. (OK, 500-euro bills.) I’m most useful to society if I point that out.

PS. NGDP growth (or growth expectations) is the proper way to measure the stance of monetary policy. In other words, M*V. But some commenters demand “concrete steps.” So in response I sometimes point out that a certain slowdown in NGDP growth was triggered by a target rate increase at the central bank. Then commenters complain “but you told us interest rates weren’t the right indicator.” I can’t win.

READER COMMENTS

Chris Wegener

Oct 30 2014 at 12:27pm

I see Japan doing badly until the US and Europe fall back to join them. Suggesting that because the Europeans, through austerity, are now equal with the Japanese in no way suggests that Japan has improved but rather that Europe is doing really badly and we are not doing much better.

MichaelByrnes

Oct 30 2014 at 2:37pm

I’m confused by this:

“The enormous difference in the performance of countries like Greece and Italy relative to Germany and Austria is a supply-side story. They face the same monetary policy.”

The first sentence seems straightforward and correct. I’m Not sure what you mean by the second. Obviously, “facing the same monetary policy” as Germany hurts Greece. Greece needs more monetary stimulus than Germany, so one could argue that they don’t face the same monetary policy.

Still your first sentence is correct. Monetary policy isn’t the only thing or the biggest thing stopping Greece from being Germany.

Scott Sumner

Oct 30 2014 at 4:39pm

Chris, I should have been clearer. Obviously Japan also had the same bad monetary policy in the post-2008 period as the US and Europe. But as I read the graph the gap maximized around 2000, then got steadily smaller, regardless of whether both regions were expanding (2002-07) or both regions were contracting (2008-now.) That was my point. Japan seems to be adjusting back to its natural rate.

But I understand that other interpretations are possible, it’s just that the one I gave seems the most straightforward. Many people claim America in 2000-2007 was an overheated housing bubble, but even then Japan was catching up.

Michael, Here’s an analogy. Texas has done better than Louisiana for many decades, for structural reasons. Both faced the same monetary policy. Given that divergence, Louisiana might have done slightly better relative to Texas with its own monetary policy, but I doubt the long run effect would have been very large. On the other hand, the negative effect of the bad monetary policy on the eurozone as a whole was quite large.

RPLong

Oct 30 2014 at 5:10pm

Wait a minute. That’s not fair. In the NGDPLT scenario, you assumed that the level target worked perfectly. In the inflation-targeting scenario, you assume that the inflation target failed to lift GDP.

I agree that any policy that is assumed to work will out-perform any policy that is assumed not to work. But that doesn’t seem like sound reasoning to me.

David R. Henderson

Oct 30 2014 at 6:08pm

Scott,

On the graph, what’s EA? I suspect it’s Europe but, if so, what’s the A?

Emerson

Oct 30 2014 at 6:09pm

In the medium term example,

Is the point that NGDP targeting will help prevent a reduction in employment (therefore maintain AD) when there is a RGDP reduction ( supply shock) ?

If that is the point, how does it work.? How can inflation help stabilize employment?

Michael Byrnes

Oct 30 2014 at 6:36pm

I don’t think Scott assumes perfect working of monetary policy.

He is talking about the monetary policy response to a supply shock that reduces real output.

Under such conditions, targeting prices would call for a more procyclical monetary policy than targeting spending.

Relative to an inflation target, an NGDP target would call for looser money during a negative supply shock and tighter money during a postive one.

Recall that the week after Lehman failed, the Fed did not cut its policy rate, [i]citing equal risks of recession and inflation.[/i] Had they been focused on spending rather than on prices, they might not have made that error.

Michael Byrnes

Oct 30 2014 at 8:08pm

Emerson wrote:

“How can inflation help stabilize employment?”

Employment responds to changes in nomial spending on output. Think of national income (NGDP) as the money available to pay workers and service debts. If NGDP falls, (some) workers will lose their jobs, (some) debtors will default. Salaries and debts are typically in nominal terms (i.e. not indexed for inflation).

Inflation, in and of itself, is not necessarily good for employment. But because salaries are nominal, and it is not presently feasible for employers to cut wages across the board in response to a fall in income/spending, employers are forced to respond to falling income by cutting staff. So a little inflation can be good if it keeps nominal soending on track.

More detail in this article by Vox’s Tim Lee (and the attched interview with Scott):

http://www.vox.com/2014/7/8/5866695/why-printing-more-money-could-have-stopped-the-great-recession

Or this one (by David Beckworth, also a market monetarist):

http://www.newrepublic.com/article/economy/97013/obama-federal-reserve-inflation-loose-money

Commander

Oct 30 2014 at 8:25pm

Michael Byrnes:

In other words, real wages can be reduced through inflation, thus facilitating employment. It’s an old ploy. Why can’t you just come out and say it?

Todd Kreider

Oct 30 2014 at 8:50pm

By time Abe “ended deflation” there really hadn’t been any for two years before he was elected as inflation hovered around zero percent. It dropped to -1 percent shortly after he was elected in late 2012.

When Japan’s GDP/capita grew the fastest in the 5 years from 2003 to 2007, the inflation rate was 0%.

Why would it be important to end 0% “deflation”?

Emerson

Oct 30 2014 at 10:38pm

And so in the median term example, during a reduction in RDGP, inflation supports employment (or at least AD).

It seems to me that a reduction in RDGP coupled with inflation used to be called Stagflation, and it did not work out so well.

Here’s a table of RGDP, Inflation and Unemployment from the Stagflation days of the 1970’s.

Year RGDP Inflation Unemp.

1972 5.30% 3.20% 5.80%

1973 5.60% 6.20% 4.90%

1974 -0.50% 11% 5.10%

1975 -0.20% 9% 8.10%

1976 5.40% 5.80% 7.90%

1977 4.60% 6.50% 7.50%

So according to the median term example, the high inflation of 1974 and 1975 is the source of improved RDGP seen in 1976 and 1977? But unemployment actually went up in 1976, 1977.

It seems that using inflation (NGDP targeting) as a means to drive RGDP and employment has been disproven – certainly in the long term.

A.W. Phillips. R.I.P.

Michael Byrnes

Oct 31 2014 at 7:22am

Ermerson,

According to your figures, NGDP growth was:

1972: 8.4%

1973: 11.8%

1974: 10.5%

1975: 8.8%

1976: 11.2%

1977: 11.1%

1. They weren’t targeting NGDP.

2. Throughout the most of the period, inflation was much higher than is advocated by any proponent of NGDP targeting. (Over a five year period, it never got lower than 8.8%, whereas Scott advocates ~2% inflation over the long term.)

3. Nevertheless, the recession of 1974-75 was less bad than that of 2008-2009. It would be stupid to led fear of another 1974-75 cause another 2008-09.

4. I assume that if Scott were running the Fed in 1973, he would have pursued a tighter monetary policy over the objections of Tricky Dick and probably gotten fired.

RPLong

Oct 31 2014 at 9:24am

Michael Byrnes –

Let me see if I understand your/Prof. Sumner’s point.

In this scenario, RGDP falls due to a supply shock (lower output). Are you suggesting that the Fed would raise rates in response to deflationary pressure?

Emerson

Oct 31 2014 at 10:56am

So in the medium term example, RDGP falls to 0 and through NGDP targeting of 5% we are left with 5% inflation.

The 5% inflation supports AD in the medium term.

So if 5% inflation supports AD, why wouldn’t 8% inflation be better? Or is 5% the optimum?

It seems like NGDP targeting may be beneficial in the short and medium term but fails in the long term.

And it seems like 1970 s stagflation disproved the concept of a trade off between inflation (NGDP Targeting) and unemployment.

Michael Byrnes

Oct 31 2014 at 12:16pm

RPLong,

If the supply shock causes prices to rise, that might be mistaken for inflation, leading the central bank to pursue a tighter policy. This happened to some extent in 2008.

collin

Oct 31 2014 at 12:21pm

[Comment removed for supplying false email address. We have tried to reach you several times. This is your final notice. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring your comment privileges. We’d be happy to publish your comments. A valid email address is nevertheless required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

Ray Lopez

Oct 31 2014 at 1:56pm

I hope people realize that Krugman’s three country graph is normalized from a baseline, but it does not compare each country to the other but rather each country to itself, from the baseline (100 in 1991). So Japan did not ‘catch up’ with the EU or USA (Japan’s GDP per person is only a little ahead of Italy’s, and behind both the UK and Germany last I checked, and way behind the USA).

Just a clarification. What Japan did was resume somewhat the *rate* of its increase after about 10 years of stagnation after 1991, but, given that it was growing like crazy in the 1980s and before, this rate arguably should be even higher than it is now.

RPLong

Oct 31 2014 at 2:04pm

Michael Byrnes –

Yes, that is true, but such a circumstance would also plausibly fool an NGDP level-targeter, if that level-targeting decision is based in any way on current or future estimated inflation rates.

But more to the point, it is not in any way clear that this is what Prof. Sumner had in mind when he gave his example.

Scott Sumner

Oct 31 2014 at 3:36pm

RPLong, No, I assumed both worked perfectly.

David, Euro area.

Emerson, Hourly nominal wages are sticky, so employment tends to follow NGDP in the short run. Thus if you stabilize the growth rate of NGDP, employment is also more stable (obviously not perfectly stable.) It’s better to ignore inflation, which is a meaningless data point concocted by government bureaucrats. It’s not even clear what it’s supposed to measure.

Commander, Whenever there is a negative supply shock living standards will fall. They may fall a little bit with NGDP targeting, or they may fall much more sharply with inflation targeting.

Todd, If they could have continued the 2002-07 policy things would have been fine. But NGDP in Japan fell sharply after 2007. BTW, it depends how you measure inflation, the GDP deflator showed much more deflation than the CPI (the figures you use.)

Emerson. The policy I am proposing is completely unlike the monetary policy of the 1970s. In 1971-81 monetary policy was highly expansionary, leading to 11% NGDP growth and also highly unstable NGDP growth. That’s why it was bad. I am proposing something lower, say 4% or 5% NGDP growth, and at a stable rate. I strongly oppose the monetary policy of the 1970s.

RGDP growth averged 3% during the 1970s. Under my proposal inflation would have averaged 2%. Is that stagflation?

RPLong, It’s impossible to say what interest rate change would produce the desired NGDP grwoth. The central bank should not control interest rates, they should be set in a free market.

Ray, Good point, I knew that but forgot to mention it. I meant that the relative loss of position vis a vis the US was regained, but in absolute terms Japan still lagged. And yes, your comment about the 1980s is extremely relevant here.

RPLong

Oct 31 2014 at 3:49pm

Then would you mind clarifying why employment must go down in the inflation-targeting scenario? Is it because you are assuming the CB would raise interest rates, as I said above, or is it due to some Phillips-Curve-type reasoning as Emerson pointed out? Or some third reason?

genauer

Nov 1 2014 at 4:53pm

@ all

look at the Krugman graph again,

shift the Japan curve 10% up,

and you get the perfect “Austrian” picture

Countries at the frontier share the same TFP progess, even with the minor details of recession years,

and the overshoot of Japan begin of the 90ties was just the run/up/down of their credit, real estate bubble

@ David R. Henderson

EA = Euro Area

originally 11 countries in 2000, now 18, next year 19 and expected to grow by about 1 per year

alternatives were

a) EZ = Eurozone, very negative tone, like bi-,tri-, ostzone for the anglo-american, soviet occuptation sectors, kinda like

“The USA never lost a war, alone the South”

b) EL = Euroland

That would imply that we share one fatherland, with common debt and/or army. Iieeeek !

Todd Kreider

Nov 2 2014 at 5:41pm

Scott,

OK, but if using Japan’s GDP deflator then you can’t say Abe ended deflation.

J.V. Dubois

Nov 3 2014 at 4:57am

“The natural rate hypothesis says that it wouldn’t matter if AS and AD were entangled in the long run, because AD doesn’t matter in the long run. Thus long run stagnation cannot be a demand-side problem.”

One quibble I have with this is that in my eyes in the long run the monetary policy is a supply side factor. So if you we assume that there are repeated nominal shocks to economy every 5-10 years we should see worse performance in countries that have bad AD management, for instance if they rely on interest rate instrument when stuck near to ZLB for almost two decades as is the case in Japan.

So in short – a single AD shock should not matter in the long run. However continually bad AD management will mean bad thing to supply in the same way that bad property rights management or bad management of other important institutions may impede growth.

Michael Byrnes

Nov 3 2014 at 8:03pm

RPLong wrote:

“Then would you mind clarifying why employment must go down in the inflation-targeting scenario? Is it because you are assuming the CB would raise interest rates, as I said above, or is it due to some Phillips-Curve-type reasoning as Emerson pointed out? Or some third reason?”

I think the new article from Jeffrey Rogers Hummel addressed this question…

http://www.econlib.org/library/Columns/y2014/HummelTaylor.html

“Inflation targeting can do a better job of dampening shocks to aggregate demand than of dampening shocks to aggregate supply. That is because a negative supply shock pushes output and prices in opposite directions, decreasing output growth while simultaneously increasing inflation. If the central bank tries to suppress the resulting inflation with a tighter policy, it will aggravate the hit to output. An ideal policy should allow the price level to rise in response to a supply-side shock, and inflation targeting does not do this. Note that with a Taylor Rule, a negative supply shock will result in a negative output gap and a positive inflation gap. The first calls for lowering the target interest rate and the second for raising it, with the two tending to offset each other.”

Comments are closed.