I’m in Zurich today to give a talk on economic inequality. While preparing my talk, I came across an article by Branko Milanovic in the Review of Economics and Statistics. It’s titled “Global Inequality of Opportunity: How Much of our Income is Determined by Where We Live?” The answer is “a lot.”

Here’s the abstract:

Suppose that all people in the world are allocated only two characteristics over which they have (almost) no control: country of residence and income distribution within that country. Assume further that there is no migration. We show that more than one-half of variability in income of world population classified according to their household per capita in 1% income groups (by country) is accounted for by these two characteristics. The role of effort or luck cannot play a large role in explaining the global distribution of individual income.

He backs up his assumption of zero migration by pointing out:

Assignment to country is fate, decided at birth, for approximately 97% of the people in the world: less than 3% of the world’s population lives in countries where they were not born.

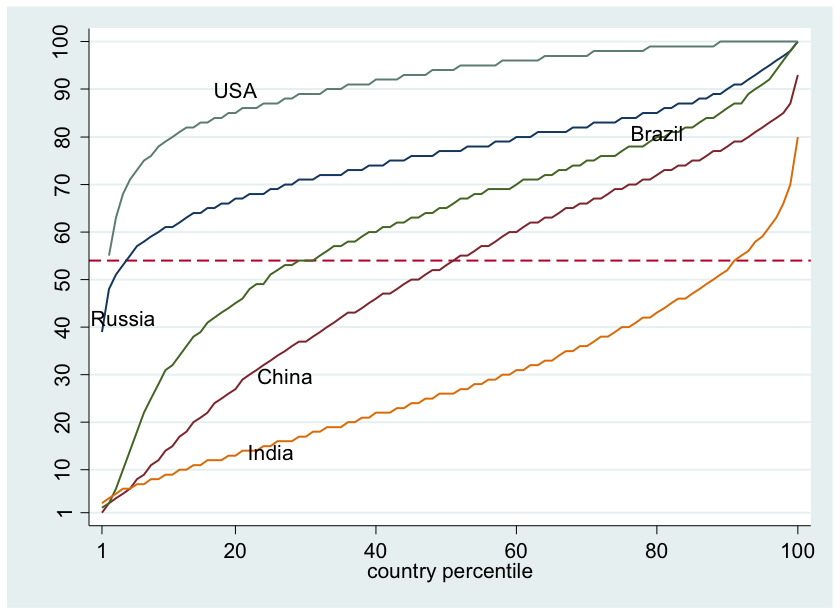

And this graph from his paper is quite striking:

Here are the axes. Tom Davies, in the comments below, has it right:

“The graph (for year 2008) shows on the horizontal axis a person’s position in their own country’s income distribution, and on the vertical axis, a person’s position in global income distribution. Thus, the poorest Americans (points 1 or 2 on the horizontal axis have incomes that put them above the 50th percentile worldwide). Note that 12% of the richest Americans belong to the global top 1%.”

Here’s why I got it wrong: I was looking for an uploadable version and I went to the article I linked to. It turns out that it’s a different graph: it’s actually more informative than the one in the Review of Economics and Statistics. But the graphs tell the same story.

I found an uploadable version of the above graph here.

Do you notice a huge contradiction between the last sentence of the abstract and the whole message of his article?

READER COMMENTS

Tom Davies

Jun 11 2015 at 6:06am

I’m confused by the description of the graph — on the page you link to it is described thus “The graph (for year 2008) shows on the horizontal axis a person’s position in their own country’s income distribution, and on the vertical axis, a person’s position in global income distribution. Thus, the poorest Americans (points 1 or 2 on the horizontal axis have incomes that put them above the 50th percentile worldwide). Note that 12% of the richest Americans belong to the global top 1%.” which seems much more likely than your “The label on the vertical axis is cut off. It’s Income in Purchasing Power Parity dollars (2008). It’s logarithmic. The horizontal axis is the income level of poorest (by which Milanovic means lowest-income) German percentile.”

Have the graphs got switched?

Tom

Richard O. Hammer

Jun 11 2015 at 6:11am

An off-topic question. You write, David:

You certainly have become a saught-after speaker. I would like to know why and how this happened, if you can write about this sometime. Have you long wanted to be more on the podium?

mucgoo

Jun 11 2015 at 6:31am

The vertical axis is global income percentiles, not log income.

http://www.iariw.org/papers/2013/milanovicpresentation.pdf

Winton

Jun 11 2015 at 7:10am

i guess luck doesn’t play a large role in where we happen to be born.

David R. Henderson

Jun 11 2015 at 9:05am

@Tom Davies,

Thanks. Correction made.

@mucgoo,

Right you are. Correction made.

@Richard O. Hammer,

You certainly have become a sought-after speaker. I would like to know why and how this happened, if you can write about this sometime. Have you long wanted to be more on the podium?

It’s happened on the margin, bit by bit. I do enjoy speaking. I enjoy the interaction with audiences, saying things clearly so that people understand, making them laugh, learning what people’s concerns are, and occasionally (but not often :-)) learning that I was wrong. I also like making money and I don’t like to be away from my wife very much. I’ve always wanted to do this, but bit by bit, people have been willing to pay my high prices. I think it’s because my writing in Regulation and on the blog have led to more visibility for me.

I give zero-price talks in the Monterey area a couple of times a year at Rotary Clubs and similar venues because the cost is low and I like feeling like part of the community and making myself more visible in the community. The travel cost is virtually zero. But I’ve always said no when the Rotary Clubs that are more than 45 minutes away have invited me because there’s no fee, not even reimbursement for miles.

Richard O. Hammer

Jun 11 2015 at 10:48am

Thank you David for your answer to my question.

Now to answer your question: The last sentence of the abstract seems loosely connected at best (I suppose, but I have not gained access to Milanovic’s paper).

Luck, in my thinking, would explain the country and family of a person’s birth. So the luck part of the last sentence does not follow. It seems so wrong that I wonder if it is a typo, a missing negation.

Effort may be more consistent with his whole message. But (judging from the abstract) I doubt that his data contain a measure of effort; so the effort part might be only Milanovic’s logical conjecture. And effort might explain much of the variability within a country. From the chart I might guess that effort in India could get you from 2 to 80.

Conscience of a Citizen

Jun 11 2015 at 9:03pm

Milanovic’s use of the word “country” conflates two different things: (1) geographic location and (2) local society. His paper should be retitled “Global Inequality of Opportunity: How Much of our Income is Determined by Who We Live Among?”

Though geography can make a difference (as when North Sea oil revenues boost Norwegian incomes) overall it is much less important than local society. No one thinks that economic disparities between Austria and Hungary, for example, have more to do with geographic endowment than society.

Suppose Milanovic had written more exactly that two characteristics which explain more than half of income variability are (a) which of about 200 fairly distinct and politically-organized groups of people one is born into, and (b) the distribution of incomes inside that group.

Then readers could recognize more easily why mass migration might not produce the income gains promised by some boosters. After all, if you greatly alter the membership of a group of people you must expect it to perform differently.

In the interview you linked, Milanovic does not promote migration as a panacea for income inequality. (The paper is inaccessible to me.) He probably understands all of the following:

Moving people to new geographic locations can redistribute income but not increase it much (some low-value geographic endowments might be exploited by sufficiently-cheap labor, but today’s world offers few such opportunities). If you doubled the population of Norway each resident would “get” only half as much oil bounty (arithmetically– the actual distribution would depend on politics, which goes right back to the question of “society”).

Adding people to social groups can increase incomes only slowly if at all. Doubling the number of so-called “Norwegians” by adding people from somewhere else would cut the per-capita industrial capital used by Norwegians (old and new together) in half (and disrupt Norwegian society a lot).

Labor productivity depends on industrial capital per-worker as well as human capital and other factors usually summarized as “institutions.” The groups of people which Milanovic calls “countries” have different distributions of human capital (see Garrett Jones) and different institutions.

Poor-society people who join (“migrate into”) a richer society (a) reduce the richer society’s per-worker industrial capital; (b) reduce its mean per-worker human capital; and (c) disrupt the richer group’s institutions by bringing different goals and habits into the socio-political calculus and by fueling new rent-seeking behavior in the combined society (“country”).

So naive extrapolation of the income gains available to poor people from joining richer groups (“migration”) that assume constant marginal wages may not be valid.

Roger McKinney

Jun 11 2015 at 11:34pm

Socialists make a big deal of the obvious fact that people don’t choose where they are born. They conclude that the distribution of wealth is therefore unfair.

But it’s not true that luck determines where a person is born. That decision is up to the parents. Parents choose where their children are born.

And it’s not an accident that the rich places in the world are rich. That wealth happened through hard work and savings and the many wars needed to create freedom, especially free markets. Luck had nothing to do with any of it.

Shane L

Jun 12 2015 at 6:09am

“But it’s not true that luck determines where a person is born. That decision is up to the parents. Parents choose where their children are born.”

Well immigration restrictions and the general cost of travel for very poor people make it extremely difficult for many parents to move to a new place.

I would say it is entirely luck where one is born. No individual gets to choose their parents and the actions of those parents before one’s birth. Since location is a big determinant of income, luck is too.

(I’d also add, see how the “99%” in the US are all above 50% of the world. Those protesting in the Occupy movement in the US were relatively privileged.)

ThomasH

Jun 12 2015 at 7:50am

@ Conscience

Points a) and b) are arithmetic. Probably Conscience is thinking about a production function in which the human capital and labor of the immigrants are substitutes for that of non-immigrants so that the incomes of non-immigrant owners of non-human capital rise and incomes of non-immigrant owners of labor and human capital fall. Even in this model (migrants could bring complimentary labor and human capital) migration could be desirable if total income rises and one values the incomes of migrants and non-migrants equally.

Point c) is equally ambiguous. Even if new forms of rent seeking are introduced, perhaps that displaces other worse forms of rent seeking.

Sorry to get all liberal on you, but there is just no way to discuss this without estimates of the magnitudes of the various trade-offs.

Conscience of a Citizen

Jun 12 2015 at 2:33pm

@ThomasH

Nah. Although that production-function story is likely true, I only wish to point out something simpler: mass migration just won’t increase total income (certainly not quickly). Look at the graph. If you move a lot of people from poor “countries” (societies) to rich ones rapidly, capital-per-worker (at the destination) falls (arithmetically, as you noted) and per-capita income (on average– let’s ignore distribution for a moment) follows it down. The association between the two is very robust.

So there is no “trillion dollar bill on the sidewalk.” The more migrants, the less the marginal gain for each one.

The evidence suggests that total income will not rise, though income distribution may change (many poor migrants could gain but many formerly-rich non-migrants would lose). Even the seesaw effect (poor non-migrants gain access to a larger share of local industrial capital) can’t save the aggregate results.

If you want global income gains you have to accumulate more capital, not just move people around.

(It’s no good asking for migrants to increase productivity in destination societies by increasing the division of labor there. The global evidence is that societies (countries) can be a little above or below trend but capital-per-worker still drives income.)

And what does it mean to “value the incomes of migrants and non-migrants equally?” Does that mean that everyone deserves the same absolute income? Or that everyone deserves the same rate of change in income (first derivative, sign as well as magnitude)? Or something else?

Some people focus on the potential marginal gain to the first migrant and see that as compensating for his bad luck to be born into a poor society. But declining marginal returns to migration mean that only a small amount of global bad luck can be alleviated that way. Estimates of the “trade-offs” around migration need to account for that.

(A trickle of high-human-capital migrants can probably increase global productivity through technical innovation. Extremely-high-IQ people are rare everywhere (though less rare in rich societies which were, of course, founded by high-IQ people). The ones who had the bad luck to be born in poor societies could migrate to rich ones to find complementary highly-capitalized industries to advance. However, most people are non-innovative.)

Anon

Jun 12 2015 at 2:53pm

The huge thing that everyone here is missing is that absolute wealth/income is pretty much completely irrelevant. Almost all metrics of happiness and well-being are tied to *relative* wealth. Hence, income mobility/meritocracy within societies is much, much, much more important than between societies.

Tom West

Jun 12 2015 at 3:21pm

Conscience of a Citizen

The evidence suggests that total income will not rise

Because, of course, workers can’t increase their human capital. That would be why, for example, China is exactly as wealthy as it was 50 years ago…

The major point of immigration is that it allows people to unlock their personal capital right now which increases over-all wealth, rather than waiting for internal reforms that may or may not occur.

Let’s hope that Canada never decides to commit itself to economic irrelevance by listening to your advice. I work in the high tech sector, and without immigrants, I’d have few coworkers and no job…

Conscience of a Citizen

Jun 12 2015 at 4:39pm

@Tom West

Your high-tech-sector colleagues are small numbers of high-human-capital migrants. Their experience (and yours) will not scale out to large numbers of low-human-capital migrants.

The returns to “unlocking personal capital” diminish rapidly as you scale up. No one can “unlock” his personal capital except by finding some complementary industrial capital embedded in productive institutions.

The more people you move, the less additional value each one unlocks. That is the point I’ve been trying to put across. You must not say “if a hundred thousand high-human-capital workers each year (Canada gov’t link) increase their wages (say, from India) 5x by moving to Canada, then millions of subsistence farmers per year can also increase their incomes 5x by moving to Canada.” (On a short timescale.)

Not only must additional migrants utilize smaller and smaller shares of industrial capital (that effect alone produces diminishing marginal returns) but low-human-capital migrants degrade the institutions, reducing productivity (and therefore returns to migration) even more.

Look at this paper by Robert Hall and Charles Jones which explains how institutions (they prefer the clearer term “social infrastructure”) relate to productivity. Then read Garrett Jones “IQ in the Production Function” which documents implicitly why migrants bring a big part of their “social infrastructure” with them.

Roger McKinney

Jun 12 2015 at 10:54pm

When people say luck determines where they were born, they have to be speaking figuratively because luck is a random event and where is the randomness in marriage and birthing children? There is none. The process is totally the result of the choices of two people.

Anyone born into a poor country can blame their ancestors for failing to embrace capitalism so that their country could be as wealthy as those in the West.

Roger McKinney

Jun 12 2015 at 11:01pm

When people say luck determines where they were born, they have to be speaking figuratively because luck is a random event and where is the randomness in marriage and birthing children? There is none. The process is totally the result of the choices of two people.

Anyone born into a poor country can blame their ancestors for failing to embrace capitalism so that their country could be as wealthy as those in the West.

To suggest that where people are born is a random event suggests a strange metaphysics in which there must be a pool of souls and the members get assigned randomly to parents. But it’s a false metaphysics. There is no possibility of a person being born anywhere but where their parents live. The only way a person born in a poor country could have been born in the West is if his parents immigrated.

Poverty has absolutely nothing to do with luck.

Thomas Sewell

Jun 13 2015 at 12:53am

“Throughout history, poverty is the normal condition of man. Advances which permit this norm to be exceeded — here and there, now and then — are the work of an extremely small minority, frequently despised, often condemned, and almost always opposed by all right-thinking people. Whenever this tiny minority is kept from creating, or (as sometimes happens) is driven out of a society, the people then slip back into abject poverty.

This is known as “bad luck.” ― Robert A. Heinlein

Roger, that seems to be the kind of “luck” some of these people mean.

Conscience of a Citizen, if someone immigrates from Mexico to the SW United States and in the process increases their income 5x (as now), even as that reaches the margin, there is still a lot of room for wealth increases. At the marginal point it stopped resulting in wealth increase, people would stop immigrating. It’s a market, not magic.

Freeing people to trade with each other (i.e. labor to increase wealth in exchange for payment) will increase both local and global wealth over the long term as individuals are thus able to find the most efficient deals in the market for labor. What current immigration laws in most countries accomplish is similar to other types of massive trade protectionism.

If you saw that a car made in Mexico could be sold for 5x as much in the United States as it could be sold for in Mexico, but auto makers in Mexico were forbidden to import cars into the U.S., it doesn’t take much economics knowledge to demonstrate that removing that trade barrier is going to increase wealth in both the US and in Mexico.

When it comes to principles of economics, labor isn’t as much a special case as people seem to emotionally want to make it.

Comments are closed.