The standard story of the Great Recession has housing play a key role. There were lots of subprime mortgages, and when the housing bubble burst there was a big increase in defaults. This led to a banking crisis and a general fall in aggregate demand.

I’ve suggested a different interpretation. Instead of the housing crisis getting worse and worse, until it brought down the financial system and pushed us into recession, the recession of 2007-09 dramatically worsened the housing bust, and led to a much more severe banking crisis. It’s not unusual for a big drop in NGDP growth to lead to a financial crisis, and 2008-09 saw the biggest drop since the 1930s. I often use the analogy where someone gets a cold, which gradually turns into pneumonia. They might erroneously assume the initial cold got worse, not that a viral illness turned into a very different bacterial infection. A new NBER study by Fernando Ferreira and Joseph Gyourko (summarized by Les Picker) seems to provide evidence that something fundamental did change after 2008:

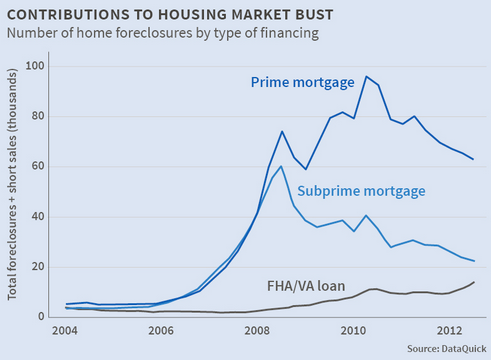

The researchers find that the crisis was not solely, or even primarily, a subprime sector event. It began that way, but quickly expanded into a much broader phenomenon dominated by prime borrowers’ loss of homes. There were only seven quarters, all concentrated at the beginning of the housing market bust, when more homes were lost by subprime than by prime borrowers. In this period 39,094 more subprime than prime borrowers lost their homes. This small difference was reversed by the beginning of 2009. Between 2009 and 2012, 656,003 more prime than subprime borrowers lost their homes. Twice as many prime borrowers as subprime borrowers lost their homes over the full sample period.

The first part of the housing bust (2006-08) is fairly well understood. But the first part wasn’t the problem. Ben Bernanke testified (quite correctly) that the losses were not enough to threaten the US banking system. The unemployment rate barely changed from January 2006 to April 2008, despite housing construction falling in half. Even in the spring of 2008, the consensus of economists did not predict a recession, despite the fact that the subprime debacle was well understood. And they were right to not predict a recession, or at least a severe recession, as the key mistakes had not yet been made.

So then what caused the Great Recession. What had not yet happened in the spring of 2008? The answer is simple, the great NGDP crash of 2008-09 caused a similar decline in RGDP. And this was caused by an excessively tight monetary policy. In this recent post, I point out that elite opinion is beginning to catch up to market monetarists, recognizing that low interest rates and QE don’t mean easy money, and that you need to look at other indicators like TIPS spreads and equity prices. (Or better yet, NGDP futures.)

Once NGDP started plunging, the real estate market took another deep plunge. Now even states that avoided the subprime bubble (like Texas) were swept up in the downturn. As real estate prices fell much further than most expected, even prime loans came under stress. Bernanke was right that the subprime bubble popping wasn’t big enough to bring down the banking system, but this much larger crisis was. Again, from the NBER newsletter:

None of the other ‘usual suspects’ raised by previous research or public commentators–housing quality, race and gender demographics, buyer income, and speculator status–were found to have had a major impact. Certain loan-related attributes such as initial loan-to-value (LTV), whether a refinancing occurred or a second mortgage was taken on, and loan cohort origination quarter did have some independent influence, but much weaker than that of current LTV.

The authors’ findings imply that large numbers of prime borrowers who did not start out with extremely high LTVs still lost their homes to foreclosure. They conclude that the economic cycle was more important than initial buyer, housing and mortgage conditions in explaining the foreclosure crisis. These findings suggest that effective regulation is not just a matter of restricting certain exotic subprime contracts associated with extremely high default rates. [Emphasis added.]

The more we know about the Great Recession, the more it looks like the predictable result of a massive contractionary monetary shock in 2008. Over at TheMoneyIllusion I have a new post discussing one of the Fed’s key decisions, which contributed to that shock.

PS. I presume someone will question my claim that economists were right not to predict a recession in the spring of 2008. Here’s an analogy. Two economists observe a die toss. One predicts 1 or 2, the other says it will be 3, 4, 5 or 6. The actual result is 2. My claim is that the economist who got it wrong made the better prediction. On average, he would have been correct. My view is not popular among economists. Like astrologers, economists show respect to those in their community who have made successful guesses about business cycles and asset price movements. One even won a Nobel Prize.

READER COMMENTS

foosion

Sep 12 2015 at 8:43am

Causation is not necessarily linear – not a simple this caused that, whether “this” is housing or financial.

A small movement in this can lead to a small movement in that leading to a larger movement in this, etc. Teasing out the triggering event is not paramount. It could be the flapping of a butterfly’s wings. Once the cycle started, it was self reinforcing.

That’s not to say that monetary policy couldn’t have stopped the cycle or didn’t exacerbate it. You’re spot on regarding the Fed.

Daniel Kuehn

Sep 12 2015 at 9:03am

I think foosion’s point is important and although I agree this is the broader narrative, when people take the time to lay things out in detail they recognize that the recession is important causally for housing and banking. I remember in 2008 at the Urban Instute hearing from the people in the Metro and Housing center that the weak labor market was the big reason why people were having mortgage trouble. I don’t think there’s any good reason to think of causation going in just one direction though.

Scott Sumner

Sep 12 2015 at 10:01am

foosion, In other posts I don’t just claim that monetary policy didn’t stop the recession, I claim it caused the recession, through affirmative policy steps beginning in 2007.

Agree about the butterfly effect, but this example has implications for why the Fed screwed up, not how the Fed screwing up had effects on the economy.

Daniel, I gave one “good reason”. There was almost no change in unemployment between January 2006 (peak of boom) and April 2008, by which time housing construction had more than fallen in half. And even the tiny increase in unemployment that did occur is more plausibly linked to the tight money policy that began in late 2007 than to the housing decline.

David R. Henderson

Sep 12 2015 at 10:02am

Which one won the Nobel Prize?

John Hall

Sep 12 2015 at 10:42am

I still think this is your most controversial idea.

Philip George

Sep 12 2015 at 11:01am

Just out of curiosity. What caused “the great NGDP crash of 2008-09”?

Mind you, I am not questioning the monetary underpinnings. The second graph on http://www.philipji.com/item/2015-09-06/a-fed-rate-hike-wont-have-adverse-results-for-now shows the monetary contraction: YoY growth falling below 0% in 2008-09 after once falling below 0% in 2006-07.

marcus nunes

Sep 12 2015 at 1:50pm

Scott, I´ve held that view for a long time:

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2012/10/27/the-housing-boom-financial-crisis-the-great-recession-3/

E. Harding

Sep 12 2015 at 2:19pm

“And they were right to not predict a recession, or at least a severe recession, as the key mistakes had not yet been made.”

-So the people that did predict a recession (e.g., Dean Baker) were wrong to predict a recession? Why so? Their reasoning wasn’t irrational.

Also, what caused the NGDP plunge while rates weren’t rising? What caused the fall in the equilibrium interest rate, to use your manner of phrasing?

“I presume someone will question my claim that economists were right not to predict a recession in the spring of 2008.”

-I do.

“Here’s an analogy. Two economists observe a die toss. One predicts 1 or 2, the other says it will be 3, 4, 5 or 6. The actual result is 2.”

-As I’ve stated in my other response to this analogy, that really only works when the outcome is genuinely random and unpredictable. The more predictable the outcome, the more questionable the wrong prediction.

“My claim is that the economist who got it wrong made the better prediction. On average, he would have been correct.”

-Even here, I very strongly doubt it. Has any recession actually been predicted by the economic consensus? If economists, on average, never predict recessions, they have a pretty weird view of the economy.

“My view is not popular among economists. Like astrologers, economists show respect to those in their community who have made successful guesses about business cycles and asset price movements. One even won a Nobel Prize.”

-Recessions are more predictable than whatever astrologists try to predict.

sourcreamus

Sep 12 2015 at 4:36pm

Was the slowdown in NGDP intentional or unintentional by the Fed?

What was the mechanism used to slow down NGDP?

Scott Sumner

Sep 12 2015 at 5:05pm

David, Robert Shiller.

Philip, Tight money. Check out my link to the Gavyn Davies post.

Marcus, You were one of the few.

E. Harding, After the housing industry slumped the Wicksellian equilibrium rate fell.

I don’t agree that recessions are predictable.

Sourcreamus, Some of each. Intentional in early 2008, in order to slow inflation. Later in the year it fell by more than the Fed wanted.

bill

Sep 12 2015 at 5:17pm

One interesting memory of mine from late 2007 and early 2008 is that Rising Interest Rates would kill the subprime borrowers due to so many of the subprime mortgages being ARMs. We may never find out since we’re 7-8 years on and rates haven’t started rising yet.

Regarding Baker, you have to read his housing paper from August of 2002. Per that paper, housing prices were then 11% to 22% out of whack. Clearly that prediction, which was very well thought out, proved inaccurate.

E. Harding

Sep 12 2015 at 11:35pm

@ssumner

-Sure, I agree with that, but I also think the impact of the Lehman failure and the government policy response’s impact on expectations was just as important.

I expect the next recession to arrive by the end of the decade. 2016 is too early, 2020 is probably too late.

Peter Gerdes

Sep 13 2015 at 4:55am

[Comment removed pending confirmation of email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

ThomasH

Sep 13 2015 at 9:36am

Scott,

Do you have a blow-by-blow account of the Fed mistakes that led to the fall in NGDP? Should they have been at the ZLB sooner? Started QE sooner, in larger amounts. Just saying “monetary policy was too tight” sounds to the not already persuaded like a tautology.

Daniel Kuehn

Sep 13 2015 at 1:55pm

I’m not sure I agree it’s a good explanation. Would we expect a big impact on employment outside of construction before the financial crisis? I would have thought housing had its biggest effect insofar as the housing crash affected relevant securities markets (and therefore banks).

To repeat, I’m agreeing with you that NGDP problems caused the housing crisis and the financial crisis in ways that a lot of people don’t appreciate (at least when they’re talking casually), I’m just agreeing with foosion that causation is unlikely to run in one direction.

bill

Sep 13 2015 at 3:46pm

Irrational Exuberance came out in March of 2000. Perfectly timed. The book built on themes that Robert Shiller had been speaking about since 1995. So like most “bubble” calls, it was way too early. Imagine not buying stocks because the Dow was at 3000?

Jose Romeu Robazzi

Sep 14 2015 at 7:28pm

Prof. Sumner

I think that the plunge in NGDP growth rates is somewhat difficult do embrace because it is not, at least to my understanding, a “structural” answer. What caused the fall in NGDP then? Because NGDP is just an indicator. Like you like to say, never reason from an indicator change. If NGDP growth rate was falling, that happened either because money supply was decreasing, or because money demand as rising (velocity going down). We know that money supply was not decreasing, actually it seemed to be increasing, therefore, that leaves us with money velocity going down even faster. And why is that? My hypothesis is that some players were highly leveraged, and most of the players in financial markets knew it, so, there was a flight to quality (more demand for money or money substitutes) and sharp reduction in velocity followed. I have been following your posts since a short time, and did not (unfortunately) follow them back during the events that unfolded in 2008, but I noticed you rarely talk about financial sector and leverage. Maybe there lies the “structural answer” that would help the NGDP story …

James Alexander

Sep 17 2015 at 5:31pm

Jose

NGDP is not just an indicator. It is the thing, the economy, Aggregate Demand.

John Wake

Oct 1 2015 at 8:03pm

I don’t get your argument.

We agree that the most important factor was, “current LTV.”

More precisely it wasn’t loan values that were changing rapidly, it was home values, so “V” was the key.

The high foreclosure rate of subprime loans sunk all home values, both prime and subprime.

The article referred to seems to be saying that the iceberg only opened 5 of the Titanic’s 16 compartments so what caused the other 9 compartments to sink?

Let’s call it the Fallacy of Decomposition.

🙂

Comments are closed.