Some Keynesians define the stance of monetary policy in terms of interest rates. This is of course a really bad idea, as it implies monetary policy is highly contractionary during periods of hyperinflation. Give Paul Krugman credit for avoiding that trap, but I’m not much happier with his criterion:

Ted Cruz somewhat surprised Janet Yellen by accusing the Fed of causing the Great Recession by tightening monetary policy in 2008; David Beckworth sort-of-kind-of supports Cruz by arguing that the Fed did in fact “passively” tighten by failing to do enough to offset falling spending.

Uh-oh: it’s starting to look a bit like the Friedman two-step, only this time done at internet speed.

By the Friedman two-step, I mean the process of argument that began with Friedman and Schwartz on the Great Depression, in which they argued that the Fed could have prevented the Depression by aggressively expanding the monetary base to prevent a sharp fall in broader monetary aggregates. This was a defensible argument, although it looks much weaker in the light of more recent developments; as I warned in 1998, in a liquidity trap the central bank loses control of monetary aggregates as well as the real economy; it’s by no means clear that the Fed really could have prevented the Depression. Still, that remains a live argument.

But what happened over time — and Friedman himself was very culpable — was that the claim “the Fed could have prevented the depression” turned into “the Fed caused the depression.” See? Government is the root of all evil!

I’m really having trouble making sense of this. First of all, Krugman frequently complains that market monetarists have no influence in the conservative policy establishment. So why is he complaining when a prominent conservative takes seriously our claim that money was too tight in 2008? After all, interest rates were not yet at zero. Surely Krugman agrees with this complaint, so why is he not applauding our success?

Second, where did this idea come from that changes in the monetary base represent the Fed “doing something” and non-changes mean monetary policy is doing nothing? Suppose the hoarding of US dollars in Eastern Europe had risen strongly after the collapse of the Soviet Union. And suppose the Fed had not accommodated that increased demand with more base money. And suppose that as a result interest rates in the US spiked upward, and we went into recession. Would Krugman claim the Fed did nothing to cause the recession, because the base didn’t change? Or would he point to the rise in the fed funds target as a big policy mistake. “The Fed did it.” In other words, does Krugman only see inaction by looking at the monetary base in cases where the interest rates also suggest the Fed is not to blame? I suspect the answer is yes, but if you can find counterexamples I’ll amend this claim.

Also, the monetary base in the US fell by 7.2% between October 1929 and October 1930, and then subsequently increased strongly as the Fed partially, but not fully, accommodated the increased demand for base money during the banking panics. So does Krugman believe the Fed triggered the Depression with tight money, but that it got worse due to banking instability? That seems to be the implication of his claim, but I don’t recall him saying that.

In addition, the monetary base rose by 33% between August 2001 and August 2007. That’s a rate of just under 5%/year, which is pretty consistent with trend NGDP growth. But then over the next 9 months it was basically flat, or perhaps 0.1% higher. Why did the Fed suddenly slow the growth rate of the monetary base? In Krugman’s worldview is that sudden slowdown a tight money policy? It would seem so. Does that count as doing something? I don’t know. Does anyone recall Krugman complaining about the sharply slowing growth in the monetary base in late 2007 and early 2008? I don’t recall him complaining. So then why is the monetary base suddenly the criterion for the Fed doing something?

Yes, just as in the 1930s, the initial slowdown in the base led to near zero interest rates, which increased base demand sharply in late 2008. So just as with interest rates, the base is not a reliable indicator of the stance of policy.

If the Fed had adopted a steady growth target for the monetary base, then I suppose I could understand Krugman’s claim. But the Fed claims to be targeting inflation, which began plunging in late 2008. They also target stable employment, and employment also began plunging in late 2008. Shouldn’t we hold them accountable to their actual announced policy goals, and not some monetary base aggregate that no one pays attention to, and even the old school monetarists didn’t want to target?

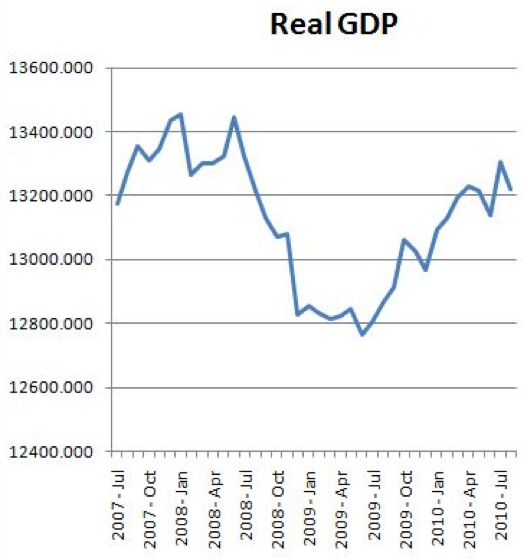

If a bus driver careens off the road at a sharp turn, is the driver exonerated if he was steering straight ahead, and the road suddenly curved? Krugman seems to think that libertarians believe bus drivers should never turn the steering wheel. That’s a caricature of our views. And he suddenly seems awfully forgiving of the Fed when anti-government conservatives make attacks on it. Suddenly Ben Bernanke is his ally again. The Fed’s not to blame. And this despite the fact that at no time between June and mid-December was the economy even at the zero bound, and yet almost all the damage was done in that 6-month period:

[Monthly estimates from Macroeconomics Advisors]

Ben Bernanke has said that neither the money supply nor interest rates show the stance of monetary policy, you need to look at NGDP growth and inflation. By those criteria money became really tight after mid-2008.

Ben Bernanke now says the Fed erred in not cutting rates in September 2008, after Lehman failed.

Frederic Mishkin says that you need to look past short-term interest rates, at other asset prices. Those other asset prices all plunged sharply in late 2008.

Vasco Curdia says you need to look past interest rates, and focus on the gap between the policy rate and the Wicksellian rate. By that criterion money was tight throughout 2008.

Unlike Cruz, these are all mainstream economists. But even with the killer standing over the body, with the gun in his hand and smoke pouring out of the barrel, some people still can’t seem to find evidence that the Fed killed the economy.

But using the monetary base as an excuse? When does Krugman even look at the monetary base, except when he’s trying to bash conservatives? I wish he had ignored who made the claim, and looked at the merits of the claim that the Fed caused the recession to get much worse with an inappropriately tight monetary policy.

PS. David Beckworth has a very good post on the “passive tightening” of 2008.

PPS. This post is not about Cruz’s views on the gold standard and/or Bretton Woods, which are never coming back and hence totally irrelevant to any critique of Fed policy. Nor is it about Cruz’s suitability to be President. It’s about how Krugman defines the Fed “doing something”.

HT: Marcus Nunes, TravisV, Christian List

READER COMMENTS

John Hall

Dec 8 2015 at 3:55pm

You might also find George Selgin’s take on the 2008 period interesting:

http://www.alt-m.org/2015/12/04/sterilization-fed-style/

Britonomist

Dec 8 2015 at 4:01pm

The problem is many conservatives don’t just act like the Fed ‘failed to turn on a sudden sharp turning’ but literally diverted the road themselves, which is inaccurate at best. It’s entirely reasonable for economists to ask “why was there such a sudden, unexpectedly sharp turning in the road?” and it’s entirely unreasonable to answer “because the bus driver failed to turn quickly enough”.

Capt. J Parker

Dec 8 2015 at 4:01pm

Dr. Krugman is just generally dismissive of monetary policy. When anyone on the right says something that might be interpreted as monetary policy can work as well or better than fiscal stabilization, Dr. Krugman’s tactic is to discredit the person and avoid debating the substance. Same thing with the post Dr. Sumner cites. So, Dr. Sumners post was about monetary policy but, Dr. Krugman’s post was about politics.

Steve J

Dec 8 2015 at 5:01pm

Your bus driver analogy has some relevance as long as you point out that in this case the bus has no brakes and due to limited forward visibility the driver is primarily using the rear view mirror to stay on the road. It seems to me there will be times it is not possible to keep the bus on the road. In those cases do we still blame the driver for crashing?

Scott Sumner

Dec 8 2015 at 6:01pm

John, Yes, a very good post.

Britonomist, Sorry, I don’t follow your analogies. Maybe you should just make the point in a simple way.

Captain, Krugman thinks monetary policy is ineffective at the zero bound, but we weren’t at the zero bound in 2008.

Steve, In the September 2008 meeting, the Fed said it was worried about high inflation. But on the day of the meeting the TIPS spreads over 5 years were at 1.23%, far below the Fed target. What should the Fed have done, look in the rear view mirror, or look ahead, into the future? They chose to look in the rear view mirror and ignore the market forecasts of inflation.

But you do raise a good point, one reason we need to create a highly liquid NGDP market is to assure that we have good market forecasts of inflation. Better visibility, to use your metaphor.

Britonomist

Dec 8 2015 at 6:08pm

Scott I was just extending your original analogy.

Scott Sumner

Dec 8 2015 at 6:11pm

Is the road the demand for base money?

Philo

Dec 8 2015 at 6:32pm

@Britonomist:

Like all analogies, that between the Fed and a bus driver is imperfect. The bus driver’s actions do not affect the shape of the road ahead, but the Fed’s actions at a given time do affect the economic conditions which its subsequent actions are supposed to accommodate.

In short, the “many conservatives” to whom you refer are correct: the Fed’s behavior in early 2008 helped to create the dire conditions of late 2008, to which the Fed then responded inadequately.

bill

Dec 8 2015 at 6:40pm

Actually, I think employment started taking a steep drop in April 2008 (though my memory is that the numbers didn’t say that at the time. I recall the big drops starting in August or Sept.). I need to see what TIPS spreads were predicting for inflation in April or May, because the historical BLS data now says we had lost a million jobs before Lehman fell.

bill

Dec 8 2015 at 6:51pm

I just checked this.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/T5YIE

I’m inclined to cut the Fed a little more slack in that the projected inflation didn’t dip below 2% until August 12, 2008. That said, from that point forward, they sure did dither. The slack being that if the current job numbers were around zero (later revised to show the large losses) and 5 year inflation projections still above 2%, I probably would have stood pat into August too. Standing pat after Lehman is just psychotic or sociopathic.

zeke5123

Dec 8 2015 at 7:28pm

Look at the slight of hand by Krugman. He turns Friedman’s position into a logical fallacy. When actually, Friedman’s point regarding the Fed was whether decisions made by the Fed were more or less likely to solve monetary problems compared to if there was no Fed. Friedman argued the Fed was less likely and therefore blamed the Fed.

This is a logical argument. Basically, it proceeds as follow: (a) the Fed could (and failed) to stop certain crashes related to monetary issues, (b) private banking system could also do the same thing, (c) based on history, MF believed the (a) was likely to do a worse job then (b), therefore (d) blame the Fed.

You might disagree with the logic, but it is a valid argument. Unlike the strawman Krugman presents.

JJ

Dec 8 2015 at 8:05pm

Scott,

If someone asked you: “What caused the Crisis in 2008?” how would you respond? Which entities would get the most blame and why?

Jhow

Dec 8 2015 at 8:09pm

[Comment removed pending confirmation of email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

Jim Glass

Dec 8 2015 at 8:17pm

I’m inclined to cut the Fed a little more slack in that the projected inflation didn’t dip below 2% until August 12, 2008.

Although at that point it was already amid the first CPI deflation since the 1950s.

CPI:

2008-07-01 219.964

2008-12-01 210.228

Another example of the difficulty of predicting the present.

And as Bernanke wrote of the time…

“…our quarterly survey of bank loan officers had revealed that banks were tightening the terms of their loans, especially loans to households, very sharply. The staff maintained its view, first laid out in April, that the economy was either in or would soon enter recession…”

… with the info they had at hand telling them credit was tightening very sharply, they might already be in a recession, and the “inflationary” worry they had was coming from a supply shock (oil prices) that was contractionary, they decided to hold tight against rising monetary-caused inflation.

One suspects they might have done better.

It’s also a practical demonstration of the arguments to revise our thinking of “price increases = inflation” by at least removing supply-shock-driven price increases from the definition, and for NGDP targeting over any kind of inflation targeting that includes price shock increases in “inflation”.

Andy

Dec 9 2015 at 2:16am

[Comment removed pending confirmation of email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

bill

Dec 9 2015 at 7:29am

I like Jim Glass’s point.

Where I really blame the Fed is that by late September, IOR should have been negative and other things like that.

I’m trying to remember 2008 as it occurred. That said, I had a job, so monetary policy was a hobby. The Fed is focused on this every single day. They watched that 5 year inflation number go from 2% in August to 1.00% the week after Lehman dropped and did nothing. And 4 weeks later, the 5 year inflation forecast was 0.00% and later negative. And instead of doing what they could do by right, Bernanke was out with Paulson pitching TARP to Congress. TARP should have been step 97. After announcing 5% NGDPLT, after negative 2% IOR, after monthly QE purchases of $300 billion,after…

Benjamin Cole

Dec 9 2015 at 9:00am

Actually…how about right now? Is the Fed too tight?

Nick

Dec 9 2015 at 9:18am

Professor Sumner,

Having completed a good portion of your new book, I am curious why you haven’t stressed aggregate supply shocks more in the Great Recession. It would seem Obamacare (see Casey Mulligan) would have played a role. Some 20+ states have raised their minimum wage over the last several years and you can add unemployment benefits to the list. Is it just that monetary policy is better able to offset those effects when removed from the international gold standard (that also assumes the Fed is willing to offset)? Or do those supply restrictions not rise to the same level of intrusiveness as the steps taken in the Great Depression.

Capt. J Parker

Dec 9 2015 at 10:22am

@ Dr. Sumner,

Yes, agree. But, this is from the Dr. Krugman July 2014 blog post I linked in my comment above:

This sounds to me to be a much more expansive argument than “monetary policy can’t compensate for a demand shortfall at the zero bound.” So, Dr. Krugman either has a more developed theory of the limits of monetary stabilization policy that he hasn’t blogged about or he is just as susceptible to letting his politics color his economic thinking as those he criticizes.

Floccina

Dec 9 2015 at 1:40pm

To me the question of Government culpability for the great depression hinges whether free banking would have performed better. Looking at the Scotland free banking era and the performance of Canada leads me to believe that it probably would have.

Floccina

Dec 9 2015 at 1:42pm

BTW isn’t Paul Krugman’s area expertise international trade and not monetary policy?

DCPI

Dec 11 2015 at 12:06pm

Benjamin Cole asks a good question. A historical debate over what was done is one thing, being able to repeat the analysis in the moment is another …

… the signs on the Street are starting to point to money being too tight. Check out MS and LUK and their travails in syndicating debt and JPM and GS with regard to loan resale efforts and collapsing prices on the secondary market and the disappearance of the second lien market since July. It is starting to feel like the summer of 2007 all over again. One possible difference, is their any dry timber like consumer debt was in ’07-’08?

Is the Fed paying attention in real-time and what would be the accurate forward-looking gauges as the rear view ones all get revised.

AS

Dec 12 2015 at 12:13pm

Every time you cite Krugman or say the name Krugman you give Krugman more undue legitimacy. Perhaps it would be more effective to ignore him completely?

Gary Anderson

Dec 13 2015 at 3:45am

So, the Fed did react to the crisis. If some say they did go too slow and money became tight so what? Clearly the housing bubble crashed because investors stopped accepting MBSs that were deeply flawed from the banks. So the banks could not continue the securitization game. So, the system of securitization broke because of massive defaults on loans that people could not afford to pay. How does the money supply fix that?

And you cannot rule out the possibility that failure to fix securitization could have been a conspiracy on the part of the Fed to deliberately cause a crash.

Comments are closed.