Several readers have taken issue with my use of the term “ADHD.” To be honest, I’m not comfortable with it either, but my reason is the opposite of my critics. Like the late great Thomas Szasz, my objection is that labels like ADHD medicalize people’s choices – partly to stigmatize, but mostly to excuse. In his words, “The business of psychiatry is to provide society with excuses

disguised as diagnoses, and with coercions justified as treatments.” I realize this is an unwelcome view, but I do have a whole paper defending it, and I stand by it.

My general claim:

[A] large

fraction of what is called mental illness is nothing other than unusual

preferences – fully compatible with basic consumer theory. Alcoholism

is the most transparent example: in economic terms, it amounts

to an unusually strong preference for alcohol over other goods. But

the same holds in numerous other cases. To take a more recent addition

to the list of mental disorders, it is natural to conceptualize

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) as an exceptionally

high disutility of labor, combined with a strong taste for

variety.

Consider how economists would respond if anyone other than a

mental health professional described a person’s preferences as

‘sick’ or ‘irrational’. Intransitivity aside, the stereotypical economist

would quickly point out that these negative adjectives are thinly disguised

normative judgments, not scientific or medical claims. Why should mental health professionals be exempt from economists’

standard critique?

This is essentially the question asked by psychiatry’s most vocal

internal critic, Thomas Szasz. In his voluminous writings, Szasz

has spent over 40 years arguing that mental illness is a ‘myth’ –

not in the sense that abnormal behavior does not exist, but rather

that ‘diagnosing’ it is an ethical judgment, not a medical one. In

a characteristic passage, Szasz (1990: 115) writes that:

Psychiatric diagnoses are stigmatizing labels phrased to resemble medical diagnoses,

applied to persons whose behavior annoys or offends others. Those who

suffer from and complain of their own behavior are usually classified as ‘neurotic’;

those whose behavior makes others suffer, and about whom others complain, are

usually classified as ‘psychotic’.

The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) 1973 vote to take

homosexuality off the list of mental illnesses is a microcosm of the

overall field (Bayer 1981). The medical science of homosexuality

had not changed; there were no new empirical tests that falsified

the standard view. Instead, what changed was psychiatrists’ moral

judgment of it – or at least their willingness to express negative

moral judgments in the face of intensifying gay rights activism.

Robert Spitzer, then head of the Nomenclature Committee of the

American Psychiatric Association, was especially open about the

priority of social acceptance over empirical science. When publicly

asked whether he would consider removing fetishism and voyeurism

from the psychiatric nomenclature, he responded, ‘I haven’t given

much thought to [these problems] and perhaps that is because the

voyeurs and the fetishists have not yet organized themselves and

forced us to do that’ (Bayer 1981: 190). Even if the consensus view

of homosexuality had remained constant, of course, the ‘disease’

label would have remained a covert moral judgment, not a valuefree

medical diagnosis.

Although Szasz does not use economic language to make his

point, this article argues that most of his objections to official

notions of mental illness fit comfortably inside the standard economic

framework. Indeed, at several points he comes close to

reinventing the wheel of consumer choice theory:

We may be dissatisfied with television for two quite different reasons: because the

set does not work, or because we dislike the program we are receiving. Similarly,

we may be dissatisfied with ourselves for two quite different reasons: because our body does not work (bodily illness), or because we dislike our conduct (mental

illness). (Szasz 1990: 127)

My analysis of ADHD specifically:

4.2. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Substance abuse is a particularly straightforward case for economists

to analyze, since it involves the trade-off between (1) one’s

consumption level of a commodity and (2) the effects of this consumption

on other areas of life. But numerous mental disorders

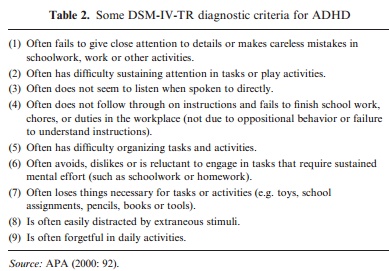

have the same structure. One way to be diagnosed with ADHD, for example, is to have six or more of the symptoms of inattention

shown in Table 2.

Overall, the most natural way to formalize

ADHD in economic terms is as a high disutility of work combined

with a strong taste for variety. Undoubtedly, a person who dislikes

working will be more likely to fail to ‘finish school work, chores or

duties in the workplace’ and be ‘reluctant to engage in tasks that

require sustained mental effort’. Similarly, a person with a strong taste for variety will be ‘easily distracted by extraneous stimuli’ and

fail to ‘listen when spoken to directly’, especially since the ignored

voices demand attention out of proportion to their entertainment

value.

A few of the symptoms of inattention – especially (2), (5) and (9),

are worded to sound more like constraints. However, each of these is

still probably best interpreted as descriptions of preferences. As the

DSM uses the term, a person who ‘has difficulty’ ‘sustaining attention

in tasks or play activities’ could just as easily be described as

‘disliking’ sustaining attention. Similarly, while ‘is often forgetful

in daily activities’ could be interpreted literally as impaired

memory, in context it refers primarily to conveniently forgetting

to do things you would rather avoid. No one accuses a boy diagnosed

with ADHD of forgetting to play videogames.

What about all the contrary scientific evidence? It’s not really contrary. The best empirics in the world can’t resolve fundamental questions of philosophy of mind.

Another misconception about Szasz is that he denies the connection

between physical and mental activity. Critics often cite findings

of ‘chemical imbalances’ in the mentally ill. The problem with these

claims, from a Szaszian point of view, is not that they find a connection

between brain chemistry and behavior. The problem is that

‘imbalance’ is a moral judgment masquerading as a medical one.

Supposed we found that nuns had a brain chemistry verifiably different

from non-nuns. Would we infer that being a nun is a mental

illness?

A closely related misconception is that Szasz ignores medical evidence

that many mental illnesses can be effectively treated. Once

again, though, the ability of drugs to change brain chemistry and

thereby behavior does nothing to show that the initial behavior

was ‘sick’. If alcohol makes people less shy, is that evidence that shyness

is a disease? An analogous point holds for evidence from behavioral

genetics. If homosexuality turns out to be largely or entirely

genetic, does that make it a disease?

Bottom line: My use of the term “ADHD” was indeed problematic because the concept itself is problematic. Then why use it? Because you can grasp my original point without sharing my broader perspective – and if I started with my broader perspective, it would drown out my original point.

READER COMMENTS

Alex

Feb 2 2016 at 12:20am

“If homosexuality turns out to be largely or entirely genetic, does that make it a disease?”

No, because the person is not suffering.

A person with a neurotic behaviour suffers terribly, he may even kill himself.

Will Wilkinson

Feb 2 2016 at 12:53am

This is embarrassing to see. Non-experts about economics should think what most economists think, not what the one economist you happen to like most thinks. Non-experts about psychiatry should think what psychiatrists think, not what the one psychiatrist you happen to like most thinks.

Graham Peterson

Feb 2 2016 at 2:05am

But, Will, it goes so much deeper than Szasz. There is an entire literature on medicalization in sociology, and there are too many takedowns of psychoanalysis and other therapies to count.

Check out the old article Being Sane in Insane Places. There exists a completely plausible hypothesis that the majority of the clinical / case study “results” of psychiatric treatment are the results of suggestion, institutionalized stigma, and experimental “demand characteristics” where experimets have actually been done.

The diagnostic regimine for ADHD is basically a checklist of bad behaviors that parents and teachers get passed by the psychiatrist. The alternative hypothesis that the mental illness itself is a moralistic social construction meant to absolve adults of the results of their interactions with children is never entertained. And speed will improve anyone’s mood and focus.

These are at least some of the reasons Jon Haidt et al. started in on the positive psychology movement.

Alejandro

Feb 2 2016 at 2:23am

Have you ever replied to Scott Alexander’s criticism of this view of mental illness?

Omar

Feb 2 2016 at 2:57am

The reason why the behaviour of people who have ADHD is compatible with consumer theory is that all behaviour is compatible with consumer theory. You observe behaviour, you assume consumer theory, and this reveals preferences. But that just assumes the problem away; it supposes that people do what they want. It’s probably close enough to the truth given paternalism as a policy alternative, but it’s not necessarily close enough for psychiatry.

People with ADHD don’t get distracted while reading because whatever train of thought popped into their heads seemed more attractive than the end of the sentence. They do it accidentally. It’s not that the costs and benefits are different to people with ADHD; we just don’t do the weighing.

[Needless to say, I’m defending myself as well as ADHD, so take this with a grain of salt]

Omar

Feb 2 2016 at 3:32am

Oh, also, IIRC the effects of speed on focus are more important for people who otherwise can’t focus. So again IIRC it’s not like it just affects everyone in the same wah.

Richard O. Hammer

Feb 2 2016 at 5:08am

Looking at the nine points in Table 2, am I correct in noticing no mention of whose ambition is frustrated by these “deficiencies”? Is this a situation in which person (or society) A is deciding what person B should be doing, and then A feels frustrated?

Where does ADHD come from? Take a perfectly good boy. Put him in a setting where a woman, who probably has limited understanding of men and who certainly has no memory of what it is like to be a boy, is assigned the task of teaching him, and probably many others, things in which he feels no interest or sees no importance.

Jim

Feb 2 2016 at 7:22am

It’s true that so-called “attention-deficit syndrome” or “hyperactivity” is more of a personality trait than a “disease”. There are substantial racial differences in allele frequencies associated with these traits. For example this trait has a low frequency in Khoisan and East Asians and a high frequency in some South American Indians.

In Yanamamo society “ADHD” is probably subject to positive selection. So in traditional Yanamamo society far from being a “disease” this trait is a good thing at least for men.

Jim

Feb 2 2016 at 7:28am

The problem with not condidering homosexuality a disease is that it is difficult to conceive of any conditions under which this trait does not entail severe loss of fitness. On the other hand in many cultures, such as for example the Yanamamo, “ADHD” as a personality trait may well increase fitness.

Jim

Feb 2 2016 at 7:35am

Aside from moral judgements about behavior traits such as homosexuality, alcoholism, schizophrenia etc. there is the empirical question of the effects of such traits on reproductive fitness. A trait such as “ADHD” might actually increase reproductive fitness in some cultures such as the Yanamamo.

Jim

Feb 2 2016 at 7:46am

Is the sickle cell trait a “disease”? The heterozygous sickle cell trait confers immunity to certain types of malaria and thus increases fitness in environments where malaria is endemic. In environments where malaria is not endemic the heterozygous sickle cell trait reduces fitness because of decreased ability to transport oxygen in the blood. The homozygous sickle cell trait reduces fitness in any environment.

Ben H.

Feb 2 2016 at 9:12am

It seems clear that some diagnoses of mental health are really just normative, ethical judgements in disguise (e.g., homosexuality). And it seems clear that some are not – if you have ever had personal experience with someone who is schizophrenic, you know what I mean. The interesting exercise seems to be to try to find some way of objectively distinguishing one from the other. Perhaps that is impossible. To me, though, perhaps a good indicator of whether something is a mental illness is an inability to change one’s behavior even in the face of a very strong desire to do so. You write that “Alcoholism is the most transparent example: in economic terms, it amounts to an unusually strong preference for alcohol over other goods.” Lots of alcoholics lose their job, their spouse, their whole lives. Lots of them kill other people through drunk driving – and yet continue to drink and drive. Lots of them end up in prison. Lots of them end up committing suicide. A great many such alcoholics would express a very strong desire to stop drinking, and yet they are unable to do so, and they feel great shame and remorse over that inability. To claim that this is all just a consequence of their personal utility function – that they really, despite their protestations otherwise, actually *want* to follow the life path they are on, and freely choose it over the alternatives – flies in the face of reason. I realize this debate goes back a long way; I have the same fundamental disagreement with Plato. But there it is. As to where ADHD might fall on this question, I would imagine that depends on the person; not everyone diagnosed with ADHD is the same.

Steve Horwitz

Feb 2 2016 at 9:17am

Describing the behavior of ADHD suffers as a “preference” only demonstrates that the speaker has not spent anytime around those who genuinely have ADHD.

Plus, what Will said.

I will be the first to agree that ADHD is often over-diagnosed and that some of its manifestations are just “what kids and adolescents do.” But even a cursory familiarity with how serious psychiatry tries to diagnose ADHD plus observing the effects that the right medication can have on those who genuinely suffer from it indicates that it’s not “preferences.” It’s no differet from an infection that one can treat with the right medication.

Unless of course you want to call infections “preferences.”

I share Will’s disappointment Bryan. You’re better than this and you are letting other priors drive your analysis in a way that you would be (and ARE) the first to call out in others.

It is you, not the ADHD suffers, who is being intellectually lazy here.

Sarah Skwire

Feb 2 2016 at 9:26am

Bryan–

ADHD is the result of a particular brain’s inability to “read” the dopamine (and other neurotransmitters) produced by the body.

The symptoms that result from that problem are not choices any more than the symptoms that result from a Type one diabetic’s body’s inability to produce insulin are.

As Will says, this is embarrassing. You’re smarter than this.

honeyoak

Feb 2 2016 at 9:36am

As someone who has ADD and takes medication for it, I must emphasize that taking the medication has changed my preferences. I use to hate details and now I love them and generally have become less tolerant of failure. For me taking medication is like putting on glasses.

RPLong

Feb 2 2016 at 9:47am

Economics as a social science catches a lot of heat from uninformed laypeople who seek to discredit its theories and conclusions for ideologically motivated reasons. One would think that economists, of all people, would be particularly resistant to claims that seek to discredit entire social sciences.

JayMan

Feb 2 2016 at 9:48am

When you have people ignorant of evolution, they make silly declarations.

Homosexuality is an example; it is, in Darwinian terms, certainly a disorder. And since it’s likely pathogenic in origin, it is literally a disease.

Psychopathy, on the other hand, is a set of personality traits on the end of a spectrum that is normally distributed in the population. It is NOT a disorder.

Alcoholism, and addiction in general, are interesting. They fall into a class of afflictions that stem from an evolutionary mismatch. They are no more disorders than altitude “sickness” is a disorder. The afflicted people are simply outside the environment to which they are adapted (in the case of addiction, one which doesn’t have the abused substance).

Scott Sumner

Feb 2 2016 at 9:51am

Bryan, You said:

“my objection is that labels like ADHD medicalize people’s choices – partly to stigmatize, but mostly to excuse. In his words, “The business of psychiatry is to provide society with excuses disguised as diagnoses, and with coercions justified as treatments.”

My view on this issue is slightly different. It’s not particularly useful to debate whether mental illness is or is not real. The more useful question is whether mental illness is a useful metaphor. You correctly point out that gays were stigmatized with the label. But it’s also true that some people who behave like what most people would regard as “jerks” are destigmatized by the mental illness label.

And the other practical question is how to address what you might call “unusual behavior”. Nothing about that question in any ways rides on the issue of whether we label unusual behavior “mental illness” or not. Thus, as you said, society might view an alcoholic as being mental ill, but it’s also true that the alcoholic may be self medicating another “mental illness” such as depression. The only question that matters is whether a particular medication, or other therapeutic procedure like meditation, makes the person better off. And the answer to that question in no way depends on whether or not we call the unusual behavior “mental illness”.

I would even say the same about coercion. I don’t know enough about mental illness to comment, but I very much doubt whether “mental illness” is in and of itself enough justification for coercive treatment. Instead you’d need (I would assume) a pretty high threshold of clearly destructive behavior. And again, I don’t see where mental illness comes into the picture. Suppose someone was not mentally ill, but liked to frequently beat up people. They found the activity enjoyable, but were not mentally ill, just brutal. And suppose a drug could stop this behavior. Should the drug be offered as an alternative to prison? Anthony Burgess would have said no, but I’m not so sure.

Or suppose I had a habit of biting my nails, but not enough self control to stop. I doubt that’s regarded as a mental illness, but if it could be stopped with a drug that has zero side effects, why not do so? It always comes down to pragmatic utilitarian questions of does this make people better off? That’s all that really matters, not labels.

David Anthony

Feb 2 2016 at 9:57am

There is probably some economic theory that could be applied to the treatment of ADHD. Adderall, a drug often prescribed for ADHD is essentially legal meth and it makes people feel great so I can see why some people would WANT to be diagnosed with it.

Dangerman

Feb 2 2016 at 9:57am

I think the biggest point this analysis misses is the metacognition of the mental health patients:

The patient may have a preference for e.g. alcohol or variety, but they want *to want* to not have that preference.

This isn’t the “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” era – psychiatrists almost never go find problems, the patient *comes to them* because the patient has a problem they want help with.

Sarah Skwire

Feb 2 2016 at 10:04am

ADHD is a problem with the brain’s ability to “read” neurotransmitters (particularly dopamine.) It has behavioral symptoms. The symptoms can exist without the structural problem, in the same way that I can have a headache without having a brain tumor. But the structural problem that causes ADHD is no more the preference or choice of the individual sufferer than the inability to make insulin is the choice of the Type 1 diabetic.

Also, as Dangerman and Honeyoak have implied, ADHD sufferers can TELL YOU what the problem is and ASK FOR HELP. Maybe we should listen?

Ben Kennedy

Feb 2 2016 at 10:19am

You are not a mental health professional and are happy to call voters irrational, in fact you wrote a whole book about it. Is this a just a thinly disguised normative judgement?

Eric Hanneken

Feb 2 2016 at 10:23am

Dangerman wrote,

I completely agree, but that doesn’t make the “mentally ill” different from others. Lots of people want to eat a better diet but well, that Oreo looks good. Lots of people want to write that novel, but there’s good entertainment on TV tonight. We all have second-order preferences that conflict with our first-order preferences.

Eric Hanneken

Feb 2 2016 at 11:05am

Also, although we may have passed the darkest ages of involuntary psychiatric care, it still happens quite a bit. Think of all the drug users who are given a choice between prison and submitting themselves to “treatment” for their “disease.”

Kevin Erdmann

Feb 2 2016 at 11:12am

I second Will and the others. I appreciate your commitment to heterodox positions. But here you sound like a religious fanatic or nativist that has strong opinions about entire groups of people even though you have no curiosity about who they really are. I suspect that mostly what you have accomplished here is to cause all of us who have known people with ADHD and other psychological challenges to have doubts about your opinions on other matters. Are you this obtuse on immigration policy, too, and I only find your arguments compelling because I am able to be obtuse about it too?

Richard O. Hammer

Feb 2 2016 at 11:20am

Will Wilkinson says (and Steve Horwitz concurs):

From my libertarian viewpoint “most economists” are halfway to Marx and far from the mean at Cato. Are you saying non-experts should ignore the Cato economists, the Austrians?

Surely a non-specialist can examine the works of a specialty, with respect and expectation to be wrong at first about many nuances. Indeed, this is the duty of one with a brain, I claim. The majority in a specialty commonly steer into a dead end, as can be seen in the history of science. The majority in a specialty often fall into cozy relationship with the state.

Jeff

Feb 2 2016 at 11:28am

Ditto that. This post comes across as completely ignorant of what ADHD actually looks like in practice and how (some) people who have it respond to treatment. Perhaps the bubble has become a bit too thick, eh, Bryan?

Nathan W

Feb 2 2016 at 11:28am

It didn’t seem in any sort of way medicalizing anything, but rather providing just a sort of way to say it.

Mark Bahner

Feb 2 2016 at 12:20pm

Oh my.

Bryan Caplan:

And how would you “formalize,” for example, atherosclerosis “in economic terms?” Or near-sightedness? Or Meniere’s disease?

Thomas Szasz:

Or we may dislike our conduct (mental illness) because our body does not work (physical illness…causing the mental illness).

Joshua Woods

Feb 2 2016 at 12:28pm

So according to Will Wilkinson non-experts about astrology should think what the experts in astrology think? You can replace astrology with religion, homeopathy or any other of the fields where an emotional desire to believe certain things swamps critical thinking processes.

The question of whether Psychiatry is a rigorous field which deserves the presumption of expert correctness is precisely the issue Bryan is raising. By his reflexive name calling Wilkinson does nothing but beg the question.

I’d also be interested to know who he thinks has sufficent expert status to disagree with the consensus opinion – given that this is the process by which a field can move forwards I think placing undue restrictions on this would be unwise. Is it just the people Will Wilkinson likes? Embarrassing.

Mark Bahner

Feb 2 2016 at 12:51pm

I don’t agree. That happened to me many times in my life. I didn’t “develop ADHD.” Mostly, I daydreamed. Or even actually fell asleep.

Richard

Feb 2 2016 at 12:52pm

Joshua, exactly correct. Sometimes the whole field itself needs to be condemned.

Isn’t the best case against psychiatry the fact that since it’s become influential, we’ve seen a large rise in drug use, crime, and illegitimacy? The job of the psychiatrist is to argue that because something is “in the brain” or a “disease” people are incapable of responding to incentives.

Thus, instead of disciplining an unruly child, raising the cost of disobedience, you take him to the psychiatrist and give him drugs. Instead of locking up the criminal, you “treat” him.

There was a time when crime was a fraction of what it was, and illegitimacy was extremely rare. Then along came the psychiatrists.

Jesse C

Feb 2 2016 at 1:06pm

Will Wilkinson: I am a professional epistemologist and I say you’re wrong.

Joshua D

Feb 2 2016 at 2:33pm

Some of what passes for psychiatry/clinical psychology is no doubt quackery. How much? That’s the question.

I prefer to think of ADHD as a way of being. No judgment. Unfortunately the ADHD way seems to be a somewhat poor match for the way of being that responds best to our one-size-fits-all schools and manufacturing/ corporate environments.

I think that’s starting to change though – I would imagine that most entrepreneurs are a decent match for the ADHD way of being, as well as many workers in the information industry.

Richard O. Hammer

Feb 2 2016 at 2:39pm

Mark Bahner

Perhaps I should have put scare quotes around ADHD: “ADHD”, since I am skeptical about the existence of ADHD outside the perception of the people doing the complaining. Those complaining people, I suppose, are expected by their job or circumstance to oversee a youngster and also, during the same timeframe, achieve some socially-determined outcome with the youngster. They have a tough job; boys tend to be boys, although this can be eased with drugs. Oh, but “ADHD” also exists, obviously, in the perception of people licensed by government, and paid by third parties regulated by government, to diagnose and drug “ADHD”.

So, Mark, I did not mean to suggest that you would have developed “ADHD” in your circumstance, because in my view ADHD is not something in the mind of the youngster. It is in the mind of the overseer who sees a way named “ADHD” to ease her task of management. Perhaps your generation in school preceded the epidemic of diagnoses of ADHD. Were others around you at the time getting tagged with “ADHD”?

Steve Horwitz says, and one or two others above seem to agree:

You may well have a good point here. I admit that I have only seen ADHD from a considerable distance. My view might be changed by more direct experience — or my view might be reinforced. I might see firsthand evidence that the people on the scene doing the complaining are the teachers or other overseers expected to get something socially-approved done with this child, and the interests of the child have little or no influence on the agenda.

It sounds Steve like you have first hand experience with ADHD. I would like to learn more about that. I hope to learn what is or was your relationship with the diagnosee?

SanguineEmpiricist

Feb 2 2016 at 3:43pm

[Comments removed pending confirmation of email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment. Please check your spam folder. We have resent the email. No one thinks what you have to say is not real. Nevertheless, your comments will not be posted until you respond to our validation email confirming your email address.–Econlib Ed.]

Kevin Thomsen

Feb 2 2016 at 4:58pm

[Comment removed. Please consult our comment policies and check your email for explanation.–Econlib Ed.]

Rochelle

Feb 2 2016 at 5:11pm

I completely disagree with the idea of ADHD as being a ‘preference’ any more than something like dyslexia is a preference not to read. Recent MRI studies have found physiological differences have found noticeable differences in the basal ganglia of people with ADHD vs those without.

Rather than viewing ADHD as an inability to focus or “a preference for variety,” it’s better seen as a disorder of executive function. Don’t think of it strictly as an inability to pay attention.

I was also skeptical of ADHD, having worked as a transcriptionist at a psychologists office and typing up a lot of ADHD evaluations. However, since my husband and my son both have ADHD and dyslexia, I’ve done more reading about it and that along with life experience has made me change my views completely.

Instrumental in that were the books of Dr. Russell Barkley, who is an expert in ADHD.He describes ADHD as consisting of three primary problems: “difficulties with sustained attention and increased distractibility, impulse control or inhibition, and self-regulating activity level…Thos with ADHD have additional problems with self-awareness and self-monitoring; working memory (remembering what is to be done); contemplating future consequences of their proposed actions, including planning, time management, remembering and following rules and instructions; self-regulating emotion and motivation; problem solving to overcome obstacles in their goals; and excessive variability in their responses to situations. All of these symptoms are subsumed under the term executive functioning, which refers to those mental abilities people use for self-regulation.”(Taking Charge of ADHD, p. 36).

Additionally, recent MRI studies have found differences in the basal ganglia of people with ADHD vs those without. In other words, it has a firmly established neurological basis. (http://www.decodedscience.org/basal-ganglia-studies-and-attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd/6074)

Does this mean everyone diagnosed with ADHD ‘really has it’? Not necessarily; it does not rule out the possibility of false diagnosis. What it does do is establish it as a real diagnosis and, fortunately, one that can be managed either with lifestyle accommodations or medication.

Thomas Szasz’s ideas, I think, are more applicable to people who suffer from substance and/or drug abuse, which actually can be described as a lifestyle preference, quite likely the result of cummulative life problems.

Mark Bahner

Feb 2 2016 at 5:21pm

Richard O. Hammer

I think experts in the matter would disagree. See, for example “Inside the adult ADHD brain.”

Mark V Anderson

Feb 2 2016 at 8:17pm

Thank you Richard Hammer. Keep fighting the good fight against those playing the expert card. Experts are wrong all the time, and it is up to them to prove to us non-experts that they are correct. If they are truly experts, they will succeed at doing this to an open minded, intelligent audience (which I contend is mostly true of commenters here).

Commenters have made convincing points that Bryan has over-stated his case. But they are far from convincing that Bryan doesn’t also have a case. I am also skeptical about ADHD. It sounds like it just describes a characteristic that is on a continuum like everything else. It seems to me that psychiatry has simply medicalized being in the 95% bracket of distractibility. As someone pointed out above, it is worthwhile to label such a characteristic because it affects ones success in society. But why call it a disease?

Miguel Madeira

Feb 2 2016 at 8:19pm

“ADHD is a problem with the brain’s ability to “read” neurotransmitters (particularly dopamine.) It has behavioral symptoms. ”

Well, in the end all of our “preferences” have behind some kind of chemical/neurological process occurring in our brains.

Jhanley

Feb 2 2016 at 8:40pm

You forgot the word “explain.” I sincerely doubt every person with the characteristics we lump under the term ADHD sees their actions as “choices” over which they have some control. They may in fact be intensely frustrated by their inability to focus.

I suffer from bipolar disorder. My grandfather, aunt, uncle and dad all did, too, as does my sister. Finding the world too painful to face, or losing my temper so badly I can’t remember what was said during the encounter, or terrifying my wife and daughters are not my preferences. I do have to wonder how you think you can tell others what their preferences are, over-riding their own experience. There’s a level of arrogance there, of contempt for others’ own understanding of their lives, that is unbecoming a methodological individualist.

Mark Bahner

Feb 2 2016 at 11:17pm

Why? Why should they be obligated to inform you? Why isn’t it up to you to become informed? (Or simply remain silent on the issue.)

Jesse C

Feb 2 2016 at 11:30pm

I’ve always thought Alzheimer’s just amounted to a strong dispreference for forming memories.

Really though, as one who envies people whose minds don’t constantly wander away from the object of desired focus, I assure you there’s more than “preferences” involved in ADHD.

Colombo

Feb 3 2016 at 6:35am

I’ve got an off-topic question.

Many people claim that “free-will is an illusion”. Is the claim that “mental illness is a myth” compatible with determinism?

P.S.: I love szaszian posts. Some feathers need some ruffling now and then.

Oscar

Feb 3 2016 at 1:16pm

One interesting thing to consider is how people diagnosed with ADHD vs.those who don’t, react to amphetamines.

The person without ADHD who takes amphetamines finds it hard to sit still and is infused with a great amount of energy. They feel a great need to talk to everyone. It’s almost like it causes them to display tell-tale symptoms of ADHD.

The person who has ADHD and takes amphetamines does not become ultra-hyper but mellows out. It slows your thought process down immensely. The drug, given the street name speed, does not act at all like a drug that deserves that moniker in the typical ADHD sufferer.

My father took one of my adderalls one day because he thought, “My son has ADD, maybe I do too.” He told me he was bouncing off the walls with energy. It does the exact opposite to me. I have heard similar things from people who took adderall but were not prescribed it. They basically get ADHD for a few hours.

JHanley

Feb 3 2016 at 2:26pm

I once met a left-wing mayor who said he hated all economists, except one. He’d found one economist out there who validated his views.

It seems evident to me that Caplan would recognize the problem there, but he seems not to recognize that he’s playing the same game here. Szasz’s views, in their stronger version at least, are not mainstream in psychology. Caplan doesn’t like psychologists, I think, but he’s found one economist out there who validates his views.

I wish he’d think about that.

Mark Bahner

Feb 3 2016 at 5:59pm

I don’t see Szasz’s views as the problem. What I see as the problem is that, from my point of view, Bryan is saying that ADHD is a “preference” (or “choice”). As others have pointed out, ADHD is a “preference” the way bipolar disorder or Alzheimer’s is a “preference.” Which is to say, ADHD isn’t a preference at all.

I think Bryan should acknowledge the abundant medical and social evidence that clearly shows that ADHD isn’t a “preference,” but is instead a medical problem deserving of sympathy and compassion.

Richard O. Hammer

Feb 3 2016 at 6:47pm

@ Mark V Anderson

Thank you for your thanks. By golly, you might be one of the fabled Remnant, as mentioned by Albert Jay Nock in his essay Isaiah’s Job.

@ Mark Bahner

Thank you for your pointer to “Inside the adult ADHD brain”. I read the first several paragraphs of that and gained new insight into how we are failing to understand each other.

I suppose that people who see ADHD are certainly correct in so far as they observe repeated, again and again, symptoms visible as behavior in a selected set of people. These observers do the humanly-natural thing when they need to talk about a repeated phenomenon: they find a name for the phenomenon.

Words commonly carry two meanings, empirical and normative, that is observable (supposedly free of value judgment) and judgmental. (Reference Philosophical Analysis by John Hospers.) I probably would agree with the empirical observations which lead many to say “ADHD” — assuming those observations could be expressed with all judgments washed off — but I would never say “ADHD” because that label is so negatively judgmental of the boy. The word I would first find to describe the empirical observations would be “bored”.

The bored boy is responding perfectly naturally (here comes my judgment) to a stupid environment, stupid expectations. Stupid, that is, given the material, the boy. But these expectations are not stupid, I allow, given the institutional setting, which I continue to judge stupid.

Our difference may boil down to our respective backdrops, to what we consider constant, what changeable. Given that the boy does not fit in the setting, is it best to change the boy or the setting? People who see “ADHD” probably have interest in the setting and naturally hope to change the boy. I have no interest in the setting but feel kinship with the boy.

A handful of people above have commented that they take and appreciate drugs which help them feel more connected with present reality. I recognize the legitimacy of their testimony. Our subject of debate divides into at least two heaps.

Rochelle

Feb 3 2016 at 8:20pm

It is specifically not called a disease. It is a disorder.

And this is the case with how ADHD is diagnosed. When we tested my son, his results for working memory and processing speed were 6 standard deviations below the norm. SIX. And this is compared to his peers in age and gender. His inattention and distractibility likewise affected his IQ score and his matrix reasoning, which is uncommon in people with ADHD. To ignore that there is a significant deficit in this area would be to ignore reality.

Mark Bahner

Feb 3 2016 at 10:18pm

@Richard O. Hammer

Wow.

Let’s start with “boy”…boys and girls, men and women have ADHD. So it would be better to say “person” than “boy.”

Second, there is absolutely nothing “negatively judgmental” about saying a person has ADHD…any more than there’s something “negatively judgmental” about saying a person has “schizophrenia”…or “Parkinson’s” or “epilepsy.”

Finally (and I’m just basing my opinion on the article to which I linked) I don’t think it’s even necessary to observe behavior to come up with at least a tentative diagnosis of ADHD. I think someone with expertise on the subject could simply look at medical test results such as functional MRI results and say, “This person probably has ADHD.”

It appears to me that you think ADHD only manifests in a certain setting…specifically school. It also appears to me you think the school “setting” could be changed, and the ADHD would somehow go away. I don’t think that’s correct.

lemmy caution

Feb 4 2016 at 11:36am

“Have you ever replied to Scott Alexander’s criticism of this view of mental illness?”

That article is persuasive.

Brian Holtz

Feb 9 2016 at 2:40pm

I’m a huge Bryan Caplan fan (and my daughter is good friends with the daughter of Bryan’s good friend Tim Kane), and I dearly want to see Caplan reply to Alexander’s criticism, which is indeed very persuasive.

Comments are closed.