When I started blogging in February 2009, I immediately got into lots of arguments about the Efficient Markets Hypothesis, which I think is “true” in the sense of being a good social science theory, a useful approximation of reality. I cited the fact that managed mutual funds tended to underperform index funds, and that those funds that did well one year often failed to repeat the next.

The counterargument was that hedge funds had consistently outperformed the markets, and that hedge fund managers were much smarter that ordinary mutual fund managers. After all, many of them are billionaires. Warren Buffett was just as skeptical as I was of the supposed forecasting ability of the “masters of the universe” that run the big hedge funds, and decided to put his money where his mouth was:

Warren Buffett continues to hold the lead in his bet that most investors are better off in a stock index fund than in a sophisticated hedge fund that charges hefty fees.

After eight years of the 10-year bet, Buffett’s chosen index fund holds a commanding lead over a collection of hedge funds even though the hedge funds performed slightly better in 2015. . . .

The low-cost Vanguard S&P 500 Admiral index fund Buffett chose is up 65.7 percent since the bet began. Protege picked five funds that bundle hedge funds that are collectively up 21.9 percent, on average.

That gap is so large that I doubt it can be closed in the final two years. And it also seems too large to be explained by any differences in the riskiness of the two portfolios. Let’s face it, hedge funds just got lucky for a few years, and their reputation rests on that hot streak.

That’s not to say the EMH is perfect; perhaps Buffett is smarter than the market, but other billionaires just got lucky. But even if that were true, even if the EMH applied to everyone except Warren Buffett, it would be a far more accurate model that the vast majority of social science theories.

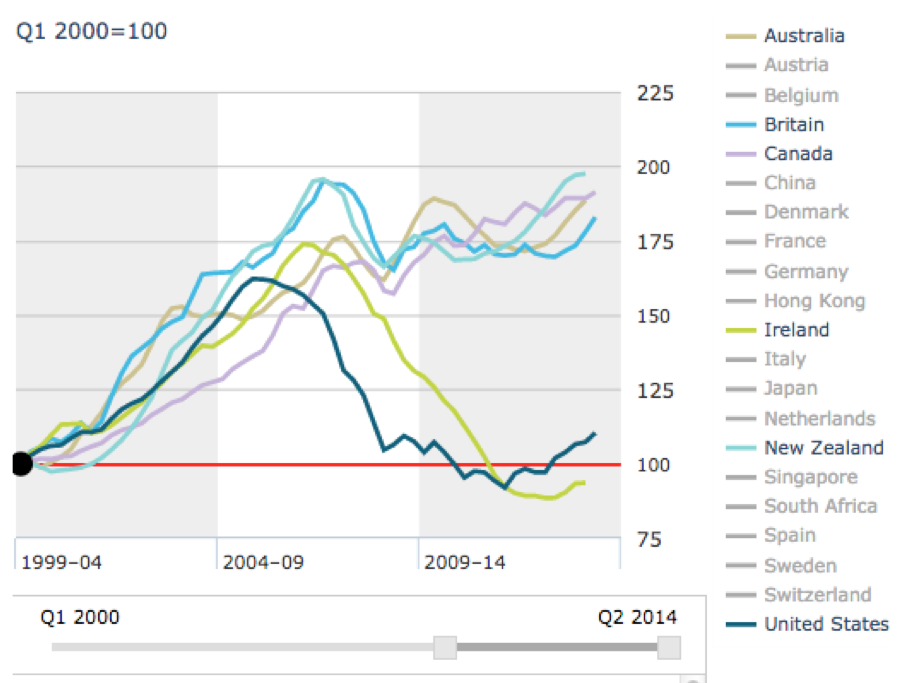

Other criticisms of the EMH have also fallen by the wayside in recent years. The other housing “bubbles” (Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, etc.) never collapsed like the US and Ireland. People who predicted the housing bubble (Roubini, Shiller, Paulson, etc.) have done poorly since. Markets have been more accurate than the Fed. Conservatives who said QE would lead to high inflation were wrong. Markets were right. Liberals who predicted the 2013 austerity might lead to a recession were wrong. Markets were right.

The EMH will always be a punching bag, because people are arrogant enough to think they are smarter than the markets. But it won’t go away—100 years from now finance textbooks will still teach the EMH.

Richard Rorty once said something to the effect that if you claim X is actually true, despite most people believing it to be false, you are implicitly forecasting that most people will eventually recognize X as true. (As there is no such thing as objective truth.) That’s how I feel about the EMH–I predict that it will eventually be regarded as true.

PS. Here are real house prices:

READER COMMENTS

Patrick R. Sullivan

Feb 24 2016 at 12:52pm

One of the best books on the EMH is unfortunately titled, ‘The Myth of the Rational Market’, by a journalist, Justin Fox. My old sparring partner Herb Gintis put up a good review of it back in 2009. From which:

Matt Moore

Feb 24 2016 at 12:56pm

Why did you choose only English-speaking countries? Or is that a coincidence?

TravisV

Feb 24 2016 at 1:32pm

In 100 years, will textbooks still be used to teach finance? 🙂

jc

Feb 24 2016 at 1:40pm

Markets are complex adaptive systems. As Dan Dennett notes, “evolution is smarter than you”.

(Always struck me as interesting, btw, how my progressive friends love to belittle conservatives who deny evolution – from single cell organisms to monkeys to humans – when they quite literally hate most modern applications of evolutionary thought, e.g., evolved preferences, human natures, complex adaptive systems that defy centralized mandates, etc.)

Kelly

Feb 24 2016 at 1:42pm

I feel like the truth is far murkier, as usual.

I agree with you insofar as that markets are generally reflective of the value of goods and are by far the best method of price discovery, but I think it is quite a stretch to argue that because people fail to predict where prices will go, those prices are “accurate” in the sense of giving us valuable information about an underlying asset.

People buy stocks and bonds and real estate for all sorts of reasons and the people moving the market in a way that made hedge funds wrong were probably buying and selling for reasons that weren’t a lot more reasonable than the hedge fund’s reasons. The only thing that made them right was that a majority of buyers and sellers agreed with them, but a lot of people agreeing on something doesn’t make it accurate.

Everyone in the world could have bet on the Panthers in the Superbowl, but it wouldn’t have made them more likely to win.

TravisV

Feb 24 2016 at 2:27pm

Patrick R. Sullivan,

Great stuff, I’d love to read Prof. Sumner’s take on Herb Gintis’s review!

Kevin Erdmann

Feb 24 2016 at 3:13pm

Ironically, the bubble-callers were relying on EMH. The bust was supposed to be a return to rationality because high prices would lead to over-building which would lead to falling rents, which would undermine homeowners’ unrealistic expectations of rising prices. You can only expect a bubble to pop if you expect some sort of tendency to efficiency.

Of course, this isn’t at all what happened. Housing starts fell first, which actually led to a period of especially high rent inflation, even as home prices were collapsing.

And, really, nothing could be more irrational than expecting a surge of housing starts in coastal California and the urban North Atlantic coast, which also never happened.

So, bubble-callers predicted something that was downright stupid (price-sensitive housing starts in San Francisco, huh?), and it never actually happened, and they are parading around as if they accomplished something. It’s especially galling since the collapse may largely been the result of policy failures coming from their misdiagnosis of the problem.

It’s as if Tonya Harding promised that she would out-skate Nancy Kerrigan, and we hailed her as a national hero for it.

Maurizio

Feb 24 2016 at 4:07pm

How do you feel about CPI inflation reaching 2.2 in the US? Now it is likely the Fed will keep hiking rates…

BC

Feb 24 2016 at 7:59pm

“And it also seems too large to be explained by any differences in the riskiness of the two portfolios.”

I don’t think that you can make that statement without knowing more about the hedge funds. If they were market-neutral hedge funds (beta=0), then the right benchmark would actually be cash. By the way, over the 8 years ended 2/16/16 (date of article), the S&P 500 outperformed the MSCI World Index 67% to 31%. Presumably, both indexes represent passive “equity beta exposure”, yet they happened to produce quite different returns. I don’t think one can really conclude anything about EMH from looking at 8-yr returns of two portfolios.

Having said all that, even if a hedge fund portfolio did produce “alpha” with respect to equities, that wouldn’t disprove EMH anyways. Maybe, it would disprove CAPM, but CAPM has much stronger assumptions, for example mean-variance preferences and single time period. The apparent “alpha” of a hedge fund could just be compensation for some other type of risk beyond equity market risk.

A

Feb 24 2016 at 9:07pm

Hedge fund managers don’t seem to disbelieve EMH. If they did, you would expect them to transition to a private equity or venture capital funding model, in order to obtain operating control of business cash flows. But most hedge funds rely on secondary market valuations. It seems like the marketing, or self-delusion, is that the market conveniently lags the managers, so that the managers consistently make money.

Bob Murphy

Feb 24 2016 at 11:36pm

Scott, you often quote Rorty on what “truth” means for scientists. Is that because you agree with him, or are you merely quoting him the way Krugman said he quoted McCulley on how Greenspan needed to create a housing bubble?

Michael Savage

Feb 25 2016 at 5:22am

Question of where to put your money is different from question of whether HF can consistently outperform. It’s a question of fees; the EMH is still undermined if the gross return to hedge funds is ahead. The net return just shows that the HF managers are taking an outsize proportion of the return for themselves.

I agree with you on EMH, but there can still be cases where HFs can exploit consistent inefficiencies. Momentum is well known. More subtly, there are lots of perversities arising from structure and regulation of finance industry that mean outsized returns from taking certain kinds of risk. Buffett himself has enjoyed superior returns from taking volatility risk (selling catastrophe insurance), which is mispriced because other firms want smooth returns and overpay to hedge some tail risks.

Darren Gillen

Feb 25 2016 at 7:40am

Would it be fair to say that the evidence on mutual fund performance as proof of market efficiency is a logical fallacy of the “if A, then B… B, therefore A” variety? (à la Barberis & Thaler, 2002)

The proposition made here is that, if prices are right, there is no free lunch for money managers and hence they can’t outperform. (If prices are right, no free lunch/outperformance)

But what the studies on mutual fund performance prove is that there is no outperformance, from which we conclude that prices must be right (No outperformance, therefore prices are right)

But this may not necessarily be right – there are many factors which can prevent outperformance, including behavioural biases, costs, institutional limitations, etc.

Dan Carroll

Feb 25 2016 at 9:54am

The average stock investor, if long-only with a portfolio that takes on similar risk as the index, cannot outperform that index by definition (and will underperform once fees are subtracted). The index is essentially an average of all investors. You would expect some distribution of returns around that average, so individual investors will outperform and underperform. Mutual funds and institutional investors drive the market, so are useful approximations of the average stock investor. Any study that comes up with a different result likely suffers from measurement error. Hedge funds customize the risk exposure, either through long-short or some other mechanism, and are not usually comparable to an underlying published index by design, which is probably why they can charge higher fees (no index means less low cost competition).

Therefore, individuals (including public policy makers) who invest differently than the average investor are taking active risk, and should evaluate whether they are qualified and have a mandate to take that kind of risk.

I always find it interesting that professors in support of EMH don’t see the logical conclusion about index investing – it is a form of free riding. Managers agree to publish transaction prices in exchange for liquidity, and index investors are arbitraging the fees required to pay for those published prices. Index investing is inherently indiscriminate – and ironically undermines the EMH in the long run. Index investing increases systematic risk and narrows individual stock dispersion around that mean. This increased covariance is especially visible within sectors and industries in recent years, due to the rise and multiplication of various ETFs.

Index investing and ETFs are steamrolling the industry, driving increased concentration in the traditional investment industry (and thus less diversity in the numbers of effective decision makers), and driving more managers into hedge funds, private equity, and other vehicles that lack the same level of transparency, thus removing transaction pricing out of the public domain. Just as one would predict.

Brian Donohue

Feb 25 2016 at 10:15am

Historically, Buffett has shied away from macroeconomic pronouncements.

But, in 1999, he was pessimistic about the US stock market and said so. The consensus then was that the old man just didn’t get it.

In 2007, I recall Buffett saying that the housing crisis would be contained- it just wasn’t big enough to bring down the economy.

By 2009, I figured he got that one wrong. But now I wonder if he was right again, except he didn’t build in the 2008 Fed errors.

FWIW, Buffett is pretty bullish on the USA today.

TallDave

Feb 25 2016 at 11:19am

It would be interesting to study how many Warren Buffett success stories one would be expect to arise purely by chance. It’s important to remember that, like global temperatures, prices are a simple scalar variable but have gargantuan underlying complexity, so it’s actually much easier to produce a model that seems correct by accident (they can only go up or down, after all) than one that is truly predictive, even if your model can hindcast perfectly.

Of course, indexing is efficient precisely because it’s free riding on active investors, just as when you passive accept the price of a pencil or laptop at Wal-Mart you are free-riding on all the pricing decisions that went into its components, as well as all the other consumers who compared retail pricing at Target or other stores. The only question is what proportion of investors can index before the markets become inefficient. I’ve seem some claims that EMH should hold true even if >99% of investors never attempt to price stocks, but fortunately we’ll probably never have enough passive investors to really test the limits.

Scott Sumner

Feb 25 2016 at 1:49pm

Patrick, Good quote.

Matt, I thought those might be the most similar, but the same pattern shows up if you add European and Asian markets. Many show prices remaining high, or going higher, some fall back.

Travis, Touche.

JC, Very good observation.

Kelly, You said:

“Everyone in the world could have bet on the Panthers in the Superbowl, but it wouldn’t have made them more likely to win.”

Sorry, I don’t follow that argument. What’s the point?

Kevin, Well if they were relying on the EMH then they obviously don’t understand it very well.

Maurizio, Actually, CPI inflation is currently 1.4%. And I don’t think anyone should pay any attention to CPI inflation, it’s useless number.

BC, I’ll accept your argument if you accept mine:

“The past 8 years may not show anything, but if they don’t then the previous arguments that hedge fund performance tended to discredit the EMH was completely, 100% bogus.”

Does that seem right? And of course your argument also suggests that hedge fund managers don’t even understand the EMH well enough to know how to make a proper bet testing the theory.

Bob, I agree with Rorty, the distinction between subjective belief and objective truth is meaningless.

Michael, I don’t agree that the EMH is undermined if they outperform not taking fees into account. Anti-EMH theories need to be useful.

Darren, The EMH theory is very useful. So the burden on EMH opponents is to find useful anti-EMH theories. And they keep falling short.

Dan, You said:

“I always find it interesting that professors in support of EMH don’t see the logical conclusion about index investing – it is a form of free riding.”

I see that issue, and have discussed it elsewhere.

Brian, Thanks, but I’m not reassured by Buffett’s bullishness. As you noted, he’s not a market timing expert.

Talldave, Probability theory says that one out of every million investors should outperform the market 20 years in a row. I’d guess that’s about 50 to 100 investors in the US.

charlies

Feb 25 2016 at 4:53pm

Vernon Smith’s lab experiments consistently show fairly wild results when the subjects trade financial-type assets, while his lab-markets quickly converge on a common stable price when trading involves consumable goods.

Have you seen that research? He sets out much of it in a recent book called “Rethinking Housing Bubbles.”

Scott Sumner

Feb 25 2016 at 5:34pm

Charlies, I have only seen summaries of those experiments. But I would not expect markets to be efficient in lab experiments, even if they were efficient in real life.

Dustin

Feb 26 2016 at 10:19am

Dan,

There is an inherently stabilizing equilibrium between index investing and active investing. As index investing increases concentrations, arbitrage opportunities will occur for under tracked securities. Active investors will look to exploit these and thereby ensure market efficiency.

charlies

Feb 26 2016 at 11:40am

Scott,

Thanks for the response, I’d recommend giving it a read. There’s two aspects of his approach that aren’t the usual behavioralist experiments:

1. V. Smith finds that some markets in lab experiments are shockingly efficient, while others are surprisingly volatile. So it’s about the nature of what’s being traded, not the fact that humans get confused in lab markets but not real markets.

2. He allows for repeated play and builds in various features that are intended to account for the John List-type response that markets become efficient in more realistic environments through feedback and learning over time.

Patrick R. Sullivan

Feb 26 2016 at 5:27pm

There’s an hour long video of Vernon Smith and Steven Gjerstad presenting the findings of their book, in 2014 here;

http://cdn.cato.org/archive-2014/cbf-10-01-14.mp4

Gjerstad’s presentation of Finland v Japan at about 25 minutes in is interesting, since he mentions Finland got out of their problems by depreciating their currency.

James

Feb 27 2016 at 4:15pm

Arguments from “markets are hard to beat” (HTB) to “markets are efficient” (EMH) do not follow. If prices were determined by rolling dice, markets would be inefficient and still they would be hard to beat.

These arguments do not even follow as inductive reasoning. Consider:

P(EMH|HTB)=P(HTB|EMH)P(EMH)/P(HTB)

and P(HTB|EMH)~1 so

P(EMH|HTB)=P(EMH)/P(HTB)

Therefore the posterior P(EMH|HTB) > the prior P(EMH) iff the prior P(EMH) exceeds the prior P(HTB). Since EMH is a more specific claim than HTB, the prior P(EMH) should be less than P(HTB).

Comments are closed.