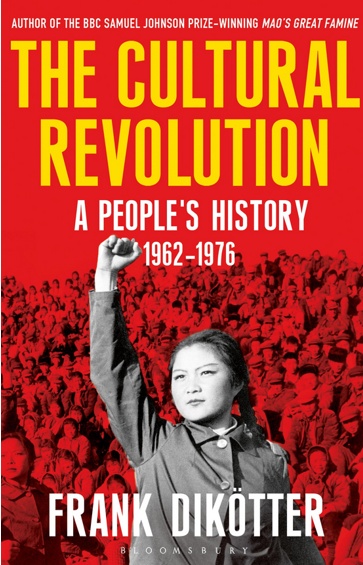

The welfare state is an appealing rationale for migration restrictions. Normally, of course, it’s a rationale for international migration restrictions. In Maoist China, however, the urban welfare state swiftly became a rationale for restricting domestic migration from the countryside, enforced by mass deportation. As Frank Dikötter explains in his excellent new The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History 1962-1976:

As soon as the bamboo curtain came down in 1949, the new regime had started emptying the cities of entire categories of people described as a threat to social order and a drain on public resources. Prostitutes, paupers and pickpockets, as well as millions of refugees and disbanded soldiers, were sent to the countryside, which became the great dumping ground for undesirable elements. In the intervening years, as the household registration system imposed strict controls on the movement of people, a sometimes deadly game of cat and mouse developed… Migrant workers had no secure status, and risked expulsion back to the countryside at any time. Once in a while, a purge would cleanse the cities of people without proper documentation. Those who were caught were sent back to their villages, while hardened recidivists were dispatched to the gulag.

In 1958, at the height of the Great Leap Forward, as targets for industrial output were ceaselessly revised upwards, more than 15 million villagers moved to the city. But three years later, with the country bankrupt, 20 million people were deported back to the countryside.

The welfare state connection:

Class background mattered a great deal in the socialist state, but ultimately the inability to earn a living was a far greater stigma. Destitute members of society, in other words, were treated like pariahs. The economy was in the doldrums, and the state wanted to reduce the number of people who represented a drain on its resources. In many parts of the country the most vulnerable categories of people were sent into exile…

In Shanghai the authorities even envisaged reducing the population by one-third. As early as April 1968, all retired workers and those on sick leave were ordered back to the countryside without pension or medical support if they lacked the proper class credentials. A year and a half later, after more than 600,000 people had been deported, including students and other undesirable elements, a new plan proposed to increase the number of people earmarked for removal to a total of 3.5 million. Half of all medical workers were to be sent off, as well as all unemployed and retired people. Those suffering from chronic illness were added to the list. Even prisons were to be relocated outside the city limits. The plan was never fully implemented, but for years the population of Shangai stagnated around the 10 million mark.

When people claim that deporting millions of illegal immigrants from the United States is “impossible,” I always furrow my brow. With totalitarian brutality, it’s totally possible.

READER COMMENTS

Kevin Erdmann

May 26 2016 at 1:49am

This is happening passively in the US today. From 2000 to 2007, about 3.8 million Americans, net, generally with low education/skills, migrated out of the cities with the highest income (NYC, Boston, coastal CA). Here we use planning commissions and price signals to do it.

Daniel Klein

May 26 2016 at 2:29am

In Britain the poor law brought on the same dynamic, with Acts of Settlement, limiting internal movement and settlement.

Adam Smith in WN had this to say about it:

“The property which every man has in his own labour, as it is the original foundation of all other property, so it is the most sacred and inviolable. The patrimony of a poor man lies in the strength and dexterity of his hands; and to hinder him from employing this strength and dexterity in what manner he thinks proper without injury to his neighbour, is a plain violation of this most sacred property. It is a manifest encroachment upon the just liberty both of the workman, and of those who might be disposed to employ him. As it hinders the one from working at what he thinks proper, so it hinders the others from employing whom they think proper. To judge whether he is fit to be employed, may surely be trusted to the discretion of the employers whose interest it so much concerns. The affected anxiety of the law-giver lest they should employ an improper person, is evidently as impertinent as it is oppressive.”

Smith, by the way, never weighs in on the poor law itself, never endorsing it nor condemning it. That is a curious omission from a book that is otherwise a quite comprehensive review of the public policy (“police”) of Britain.

Meanwhile, in the “Introduction and Plan of the Work,” the very opening of WN, he says that in Book V he shows “what are the necessary expences of the sovereign, or commonwealth.” In the spirit of enumerated powers one might say that Smith never enumerates wealth redistribution.

[Link switched to Econlib, same edition of Wealth of Nations, but direct to the paragraph.–Econlib Ed.]

Daniel Klein

May 26 2016 at 2:47am

Oops, I was hasty in my previous. The Smith quotation is about apprenticeships and corporations (guilds), not the settlement acts.

Here is what I had meant to reproduce:

“To remove a man who has committed no misdemeanour from the parish where he chuses to reside, is an evident violation of natural liberty and justice. The common people of England, however, so jealous of their liberty, but like the common people of most other countries never rightly understanding wherein it consists, have now for more than a century together suffered themselves to be exposed to this oppression without a remedy. Though men of reflection too have sometimes complained of the law of settlements as a public grievance; yet it has never been the object of any general popular clamour, such as that against general warrants, an abusive practice undoubtedly, but such a one as was not likely to occasion any general oppression. There is scarce a poor man in England of forty years of age, I will venture to say, who has not in some part of his life felt himself most cruelly oppressed by this ill-contrived law of settlements.”

[Direct link at http://www.econlib.org/library/Smith/smWN4.html#I.10.118 –Econlib Ed.]

Psmith

May 26 2016 at 7:10am

Finally, something we agree on!

Kurt Schuler

May 26 2016 at 11:01pm

The implied comparison between Maoist China and the present-day United States is, to say the least, dubious. Switzerland controls its flow of foreign workers, including requiring large numbers to return home at times. Is it too like Maoist China? Please, improve your arguments.

Comments are closed.