In recent months the rest of the world has finally begun to accept the market monetarist view that interest rates are likely to stay low indefinitely. But there’s still a lot of confusion as to the reasons why. The Financial Times has a long article on the topic; here are a few excerpts:

“The emergency to pension schemes has been caused by QE,” she said. “I don’t see how it is reasonable to ask companies with pension schemes to fill a £1tn hole and put money into their businesses as well. It doesn’t add up.” . . .

“It’s scary and it’s surreal,” says Carsten Stendevad, who heads ATP, the $110bn national Danish pension plan. “First, if you’re in the business of offering annuities, your product just became very expensive to produce. But secondly we can see that the impact of QE is affecting other asset classes as well. That’s the scarier part. There’s nowhere really to hide.”

Who’s to blame for all this confusion? Not Milton Friedman, who said extremely low rates are a sign that money has been tight. I’d blame the Keynesians. Yes, this is a bit unfair, as the more sophisticated practitioners of New Keynesianism, such as Michael Woodford, always emphasize that interest rates don’t measure the stance of monetary policy—you need to compare market rates to the Wicksellian equilibrium rate. But in the end the public fails to absorb these nuances, and instead assumes that their EC101 textbooks were teaching them that low interest rates mean easy money.

Maybe they were.

Of course if that were true, then the Fed tightening of last December would have led to higher interest rates. Instead, bond yields have fallen sharply over the past 8 months.

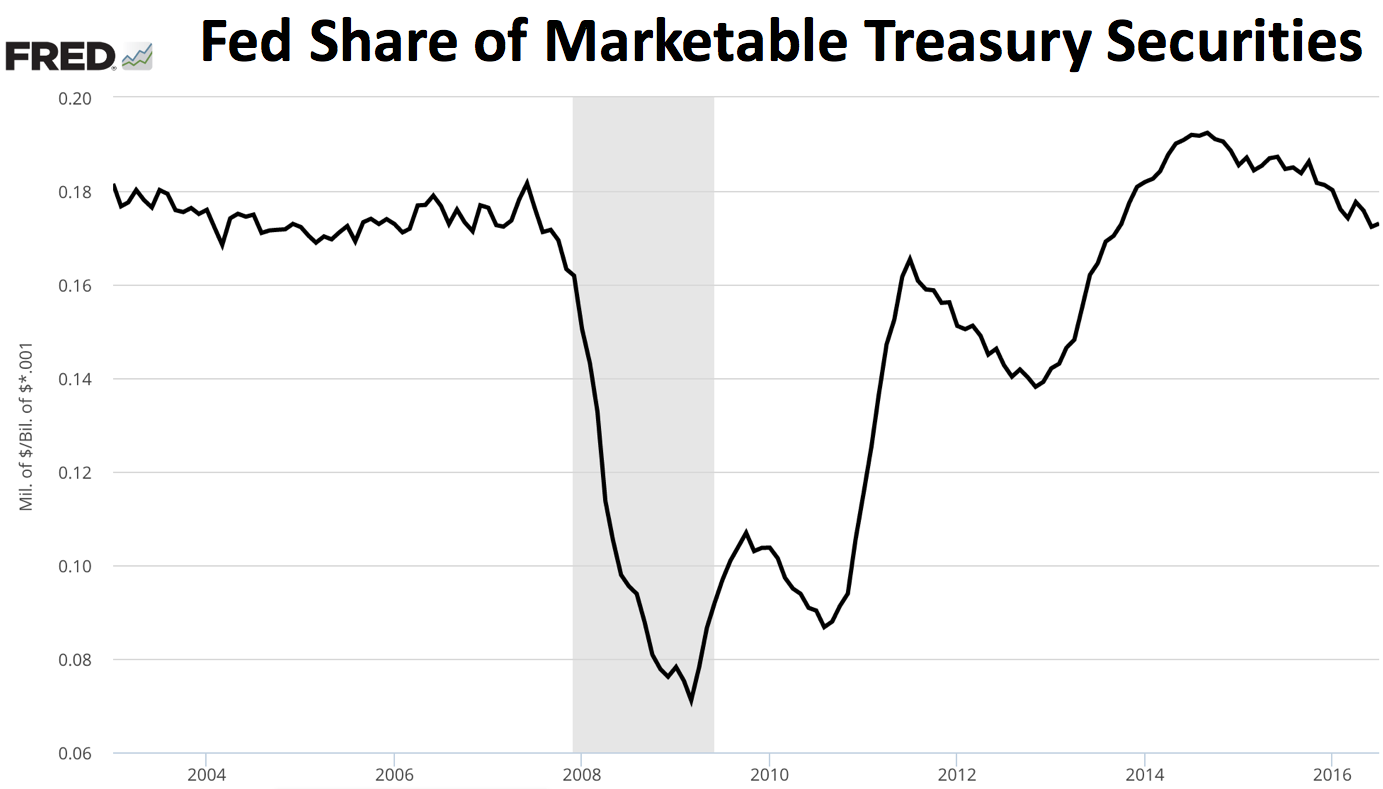

David Beckworth has an excellent post on this topic, and shows that rates have remained low even as QE has been unwinding. He shows that the Fed’s share of total Treasury debt outstanding is now lower than back in 2007, before any QE had occurred. Here’s a graph from David’s post:

Keynesians need to try harder to explain to the public that low interest rates do not imply easy money. Otherwise policymakers looking for “solutions” to the pension crisis might end up enacting policies that make the “problem” even worse, as the ECB did in 2011, when it twice raised its target interest rate.

READER COMMENTS

ThaomasH

Aug 27 2016 at 11:33am

Rather than explain that low interest rates are not easy money would be to talk about whether monetary policy should be more or less expansionary. Interest rate changes are the result of decisions to buy or sell something. The problem with Fed policy is not that “interest rates have been too high” but that it has not been buying enough stuff to keep the price level growing at 2% or NGDP at 5%.

bill

Aug 27 2016 at 3:18pm

That’s a good point. There is a difference between a zero rate with 85 billion in QE and a zero rate with a trillion or a quadrillion in QE per month.

jw

Aug 27 2016 at 3:58pm

[Comment removed. Please consult our comment policies and check your email for explanation.–Econlib Ed.]

Patrick R. Sullivan

Aug 28 2016 at 3:49pm

First the Keynesians need to understand why interest rates are NOT a reliable indicator of monetary policy. I.e., interest rates are not ‘the price of money.’ Something a lot of them simply don’t understand. Witness one of the most respected Keynesians of the 20th Century (and CEA Chair for JFK) Walter Heller’s embarrassing intellectual blunder (p.21) in 1968;

It doesn’t get any purer than that. Later in the debate, Friedman corrects his learned colleague (p.74);

If a former CEA Chairman is this confused, who can blame the general public.

Benjamin Cole

Aug 30 2016 at 9:32am

I agree with this post 100%.

The public? Keynesians?

Sad to say, one can visit the Alt-m or Cato websites and find condemnations of chronically easy Federal Reserve policies, and how the Fed kept interest rates too low for too long leading to the present problems.

s

Comments are closed.