The recent discussion over a possible 20% border tax/subsidy scheme has me more puzzled than anything else I’ve seen since I began blogging. Advocates like Martin Feldstein say it would not be a protectionist policy, as the dollar would appreciate by 25% to offset any trade distorting effects.

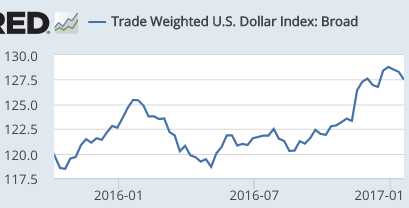

That claim seems roughly correct to me, but why don’t the foreign exchange markets seem particularly interested in the proposal? Or maybe they are interested, and I’ve simply been looking in the wrong place.

One argument is that the tax seems unlikely to be implemented, because while Congress favors the idea, Trump is opposed. But yesterday, Trump seemed to change his mind and come out in favor:

After the speech, in a brief, impromptu news conference as Mr. Trump flew back to Washington, Mr. Spicer told reporters that the president now favored the plan to impose a 20 percent border tax as part of a sweeping overhaul of corporate taxation. Only last week, Mr. Trump had dismissed the tax as too complicated, favoring his own plan to impose a 35 percent tariff on manufactured goods made by American corporations in overseas factories.

Mr. Spicer said that the plan for the tax was “taking shape” and that it was “really going to provide the funding” for the wall.

Doesn’t this make the tax/subsidy scheme much more likely? Or are markets still assuming that special interests will be able to kill the idea:

Many economists also doubt that the change would end up penalizing imports or encouraging exports. They predict that the value of the dollar would rise, offsetting those effects.

Nonetheless, many businesses in industries such as retail and energy, which rely heavily on imports, were in a panic.

In theory the dollar should rise, and the fears of retail and energy should be groundless. But where is the evidence that the dollar will rise by 25%? If that were true, shouldn’t the sudden switch by Trump have dramatically impacted forex markets?

And yet the theory of exchange rate offset seems rock solid. Perhaps the problem is that in the real world the tax will not be as uniform as theory assumes (not applying to services, for instance). Or perhaps some of the post election rally in the dollar was due to expectations of a border tax, not the response to fiscal stimulus and growth enhancing supply-side measures than many assumed at the time. But I’m dubious, and in any case the rally has been small.

For now, the lack of wild swings in the foreign markets seems like the dog that didn’t bark. I feel it’s telling us something important, but am not quite sure what.

There’s much more to be said here. It seems that Trump might be convinced that this action is protectionist, and that the revenue could be used to pay for the wall. For free traders like me that’s actually good news, because economists don’t believe this tax/subsidy scheme is protectionist at all. It might end up satisfying Trump’s desire for “protection” without doing much damage.

However, I still fear the impact of this on emerging markets with large dollar-denominated debts. And it also raises important question about monetary policy. Suppose the dollar did not appreciate—would the Fed have to tighten to prevent inflation from exceeding 2%? But that could cause prices of domestically produced goods to fall. That’s certainly not what the GOP wants to see happen. So the 25% appreciation of the dollar really is a key part of this policy.

[After I wrote this post I learned that there is some confusion as to whether Trump actually endorsed the border tax idea. Any help here would be appreciated.]

PS. If you are confused by the 20% and 25% figures thrown around, it has to do with the fact that a 20% decrease in equal in proportion to a 25% increase. Thus when I say the dollar will need to rise by 25%, I’m saying foreign currencies will need to depreciate by 20%, to offset the tax. Percentages work differently in the down direction as compared to the up direction. (There must be a more elegant way of making this point.)

PPS. John Cochrane indicates that the border tax would only apply to corporate businesses, not imports by non-corporate businesses. That has me even more confused. If true, it’s a massive problem with the proposal. The House GOP really needs to clarify what’s going on here. BTW, I highly recommend Cochrane’s entire post on taxes, I almost entirely agree with his views.

READER COMMENTS

Tom

Jan 28 2017 at 10:43am

Scott,

Wouldn’t a 25% appreciation in the dollar kill US exporters who produce in the US? Won’t they have to move their means of production offshore to compete?

There is no way the market believes a 25% dollar move is possible or probable. If the dollar rallied just 10% gold would get killed, stocks would drop, and the market would price in fed cuts back to zero.

Market Fiscalist

Jan 28 2017 at 11:07am

I can see that a policy that reduces the prices of exports and increases the price of imports will cause dollar appreciation. From a foreign perspective the supply of dollars (from exports) falls just as the demand for dollars (to buy imports) rises. But I’m not clear on why the exchange rate changes will exactly offset the effects of the policy. Won’t this depend upon the relative demand elasticities of imports v exports ?

If the decreased US demand for foreign imports drives a different decrease in the supply of dollars to foreigners than the increased demand for US goods drives an increase in demand for US dollars won’t the net short-term effect be a increased value of the US dollar plus a change (could be up or down) in the balance of trade ?

Perhaps if you assume that the balance of trade must always be zero you could reach the zero net effects conclusion – but given the vagaries of how balance of trade is calculated and the many factors that allows it be non-zero even for long periods of time its hard to see how this (zero net effect) can be a realistic conclusion as a short-term effect..

Am I thinking about this wrong ?

Steve

Jan 28 2017 at 11:20am

The more elegant way of describing 20% vs. 25%:

4/5 * 5/4 = 1

Jim Glass

Jan 28 2017 at 1:08pm

After I wrote this post I learned that there is some confusion as to whether Trump actually endorsed the border tax idea. Any help here would be appreciated.

The confusion is born of the fact that Trump himself plainly doesn’t know what he endorsed. The way he keeps confusing “border tax” with a VAT shows he doesn’t have clue about even the beginnings of tax systems. But then why should he know anything about international tax systems as a local real estate developer and marketer? Except for the deciding to run for president thing…

AlanG

Jan 28 2017 at 4:09pm

Count me as confused as well. There have been two arguments for this tax: 1) to pay for the wall and 2) to punish US firms who move jobs abroad. I still don’t understand the logic of it all. Many industries left the US over the past 40 years for low cost labor markets. Does anyone think that the textile and apparel industries are coming back? Similarly, much of the furniture industry left as well and the great cautionary tail of John Bassett III who ended up winning a trade case against China is a well known “won the battle but not the war.”

I was astounded to see that I agreed almost 100% with Professor Cochrane in the linked blog post. I’ve long felt that corporate tax structure is just all wrong (and I’m a liberal Dem!!). Better to zero it out and replace it with a VAT.

I’m not going to do any portfolio balancing until something hits the floor of Congress. From all these scattered reports it impossible to figure out what will happen or even if there will be 60 votes in the Senate.

Kevin Erdmann

Jan 28 2017 at 4:45pm

AlanG:

“Many industries left the US over the past 40 years for low cost labor markets.”

You will be ahead of 99% of the world if you reverse your intuition on this. Production and trade moves to places with high wages. This probably seems crazy upon first seeing it. But, as a first step to questioning your intuition, I would ask you to think of a country where trade with the US has especially increased over time. Then, compare labor costs in that country today to labor costs there when trade was lower. You can also think of this in a cross-sectional way. Look at countries we trade the most with today vs. countries we trade the least with. Which have high labor costs vs. low labor costs?

A confusion between levels and rates of change, along with the deceptive nature of personal experience leads almost everyone astray here.

Those factories left because other places became more productive, not because other places were cheap.

AlanG

Jan 28 2017 at 5:23pm

@Kevin Erdmann – I’m just a humbler pharmaceutical regulatory affairs guy so maybe I did get it backwards, but maybe not. Developing Asian countries (not counting Japan here) did not have an industrial infrastructure and some such as Bangladesh still are quite primitive. However, apparel industry relocation to those countries is quite striking. Labor costs were low and they still are. Along the way productivity increased but I’m not sure that Bangladeshi sweat shops count as labor productivity in a humane sense. But maybe that is irrelevant to the discussion.

Jim Glass

Jan 28 2017 at 6:10pm

Here’s a paper by Alan Auerbach (for those who may wonder, highly regarded in the tax analysis world) about related (not the same) reform ideas. At the least, it provides educational coverage of the general issue, which in my personal experience appears as exotic and unfamiliar to most economists as admiralty law is to most lawyers…

“A Modern Corporate Tax”

https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2010/12/pdf/auerbachpaper.pdf

“Two Steps to Fundamental Corporate Tax Reform … Step Two: Revamping the tax treatment of cross-border flows…

“Introducing the destination principle…

“The destination principle is already familiar in the context of taxation, because it is the approach used around the world in the implementation of value-added taxes (VATs) … applied through border adjustments … an important feature is that it eliminates the incentive that domestic producers would otherwise have to engage in profit shifting for tax purposes…

“In addition to the many benefits just described, a destination based tax is often credited with one additional advantage that is largely nonexistent, at least for a country like the United States.

“Some VAT proponents argue that providing border adjustments makes exports cheaper abroad and imports more expensive here, thereby making domestic production more competitive internationally. This argument would make sense in a fixed-exchange-rate environment, for example, if applied to a country in the Euro zone regarding its trade with other Euro-zone countries. But the U.S. exchange rate with respect to other currencies is basically flexible, and logic and analysis suggest that exchange rate adjustments will immediately offset the incipient gain in competitiveness. The same argument applies to the destination-based corporate cashflow tax. In conjunction with the expected and immediate exchange rate adjustment, taking cross-border transactions out of the tax base would make imports no more costly and export sales no more competitive…”

Provides ample references and footnotes to help expand understanding.

FWIW.

Jim Glass

Jan 28 2017 at 6:20pm

AlanG wrote:

Count me as confused as well. There have been two arguments for this tax: 1) to pay for the wall and 2) to punish US firms who move jobs abroad. I still don’t understand the logic of it all.

There isn’t any. Those are both Trumpims. The ‘logic’ behind them is so bad it qualifies for the criticism “not even bad”.

I was astounded to see that I agreed almost 100% with Professor Cochrane in the linked blog post. I’ve long felt that corporate tax structure is just all wrong (and I’m a liberal Dem!!). Better to zero it out and replace it with a VAT.

Ah, you’ll like the Aurbach paper linked to in my prior comment. Enjoy.

Jim Glass

Jan 28 2017 at 7:39pm

AlanG wrote:

Many industries left the US over the past 40 years for low cost labor markets

No, they relocated to the ‘highest productivity for the cost of labor’ markets. If all they wanted was low-cost labor they would have flooded into Haiti. Highest productivity requires the new location to provide a lot — work ethic culture, law & order, government that is supportive, financial system, physical infrastructure such as roads, power, communications, import & export transport etc….

But this accounts for *where* these businesses relocated, not *why* they did.

Developing Asian countries (not counting Japan here) did not have an industrial infrastructure and some such as Bangladesh still are quite primitive. However, apparel industry relocation to those countries is quite striking.

Look again: Haiti and *real* low-wage countries around the world (say, in Africa) versus China, South Korea, even Bangladesh. Reconsider. But again, this relates to where these textile businesses relocated abroad, *not* why they did.

To see why they did, consider Route 128 Massachusetts, often called Silicon Valley East. It’s one high-tech company after another located in one former olden-time textile-making plant after another, water wheels and all. A nation has finite, limited productive resources. New and growing high-tech companies need plants. The highly productive fast-growing high tech industry bid away those plants from the low-tech, low productivity textile industry. Limited resources moved to more productive (higher-wage paying) uses. Textile production had to move abroad to wherever it got the best deal.

Now, the people who used to work on the textile production lines who saw their businesses move to Asia concluded, “we lost our jobs to cheap foreign labor”, not “we lost our jobs to USA high tech” as they actually had. Understandably, but very mistakenly.

The same mistake is more obvious when you look at it being made during somebody else’s time.

E.g.: The portion of the US population working on farms in the USA has dropped from like 80% to less than 2%. The drop occurred fastest and most traumatically during the late 19th-early 20th centuries. The mechanism was countless small farmers not being able to pay their mortgages and going broke. Which fueled 100 years of novels, stories, movies, about greedy bankers forcing virtuous family farmers off their land, and the anti-banker populist politics of Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech.

But it wasn’t the bankers who forced all those farmers off the land — it was the tractor, reaper, new motorized vehicles of all kind, ever-rising mechanized productivity that did it.

(And that huge increase in food-production productivity which forced almost all the farmers off the land was a very good thing, our society is immensely better off for it, I think you will agree.)

the great cautionary tail of John Bassett III who ended up winning a trade case against China is a well known “won the battle but not the war.”

Would a textile company winning a trade case against China increase its productivity enough for it to bid back its former plant on Route 128 from the high tech firms that bought it?

Jim Glass

Jan 28 2017 at 7:50pm

I’m not sure that Bangladeshi sweat shops count as labor productivity in a humane sense. But maybe that is irrelevant to the discussion.

Entirely relevant, certainly to the political argument, and to the “maximize social welfare” arguments too.

In light of which I recommend one of the most frequently reprinted and downloaded stories in the history of the NY Times Magazine…

“Two Cheers for Sweatshops“, on-the-spot from Asia reporting, by the notably not-conservative NY Times writer Nick Kristof.

Scott Sumner

Jan 28 2017 at 9:32pm

Tom, The 20% export subsidy offsets the dollar appreciation.

Market, I think the offset should be perfect if the tax change is revenue neutral, which is what they are talking about. In that case (S – I) should not change, and if the current account balance doesn’t change then the exchange rate should adjust enough for 100% offset. It doesn’t depend on elasticities, in theory.

This is like a equal tax and subsidy in a product market, such as gasoline, leaving the net price to consumers unchanged.

Thanks Steve.

Larry

Jan 28 2017 at 9:42pm

How this relate to the “exports are deductible but imports are not” stuff?

BC

Jan 28 2017 at 11:52pm

I believe there is considerable doubt as to whether the proposed border adjustments will comply with WTO rules, for reasons that I don’t really understand.

Apparently, one concern is that the import tax will be applied to the full value of the good, but domestic producers are allowed to deduct their labor costs. I think the issue is that this appears to treat imported goods differently from domestically produced goods. I say “appears” because US labor income, of course, is taxed separately. I don’t know whether the issue is that the separate labor income tax doesn’t count under WTO rules or that it does count but the issue is that labor income rates may be different from corporate tax rates.

The second concern is that WTO rules distinguish between indirect and direct taxes. The WTO allows border adjustments for indirect taxes like a VAT but may not allow a border adjustment for a direct tax, which a corporate tax is classified as. I have no idea whether there is a good economic rationale for this distinction, but apparently there is a legal one.

Maybe, one reason exchange rates haven’t moved much yet is that markets don’t expect the WTO to allow the taxes.

As an aside, one under-reported objection to the proposal is that a destination-based tax may undermine tax competition and make it easier for tax rates to be raised in the future. Here is a Cato note that discusses this aspect: [https://www.cato.org/blog/concerns-about-theborder-adjustable-tax-plan-house-gop-part-ii].

Scott Sumner

Jan 29 2017 at 9:33am

Larry, The deductibility of exports is to make the tax neutral in terms of international trade.

Thanks BC. I’m told it’s equivalent to a VAT style border adjustment, plus a cut in payroll taxes. Each of those two components is individually WTO compliant. But apparently the combination is this form is not.

Market Fiscalist

Jan 29 2017 at 10:42am

‘This is like a equal tax and subsidy in a product market, such as gasoline, leaving the net price to consumers unchanged.’

OK that makes sense.

Look at each good isolation:

A 20% tax on imports increases prices , but an appreciation of the dollar by 20% backs that out.

A 20% subsidy on exports decreases prices for foreigners, but the 20% deprecation (of their currency) backs it out.

Assuming I am now looking at this correctly – this leads to the apparent paradox that a tax on imports alone is protectionist – but when combined with an offsetting subsidy on imports it is not. Can that be right ?

Market Fiscalist

Jan 29 2017 at 10:45am

typo

‘but when combined with an offsetting subsidy on imports it is not’ should be ‘but when combined with an offsetting subsidy on EXPORTS it is not’

Majromax

Jan 29 2017 at 4:37pm

> Thanks BC. I’m told it’s equivalent to a VAT style border adjustment, plus a cut in payroll taxes.

The form bandied about currently (implementation via the corporate tax) isn’t equivalent to a VAT plus payroll tax cut, because the corporate tax is a profits tax.

With a VAT system, a firm that imports machinery from abroad is essentially untaxed on the import: the VAT might be assessed at the border but then it is returned via input credit. The Ryan/Trump BAT does not have this correction.

This is far easiest to see by looking at the expense accounting of GDP. A VAT is a straightforward tax on the domestic consumption term, with all inputs to the investment term being untaxed. In contrast, the BAT has no direct, partial equilibrium effect on the domestic consumption term, and instead it is a tax on the net import term.

The BAT is not trade-neutral because other nations do not refund their assessed corporate taxes on exported goods, only consumption taxes. The BAT imposes tax harmony as if all foreign profits were tax-free.

Andrew_FL

Jan 29 2017 at 6:09pm

Belief that the markets can predict where Trump’s day to day policy whims will finally end up some indefinite period ahead of time is peak Efficient Markets Hypothesis.

You’ve taken the concept too far, is what is actually happening here.

John Thacker

Jan 30 2017 at 12:36pm

Greg Mankiw has a very nice discussion on his blog of the tax. I would look there for some clarity.

jw

Jan 30 2017 at 3:28pm

A bit of math (assuming 20% on all Mexican imports):

Mexican imports: $270B

20%: $54B

Cost of wall: $20B/3-4 years

So what it looks like to me is a classic Trump “Art of the Deal” outrageous opening position. He really only needs $5B/yr to “pay” for the wall, so he is asking for 10x to start. Granted, this may not work in politics like it might in the private sector, but we shall see.

Whether it is a straight negotiation or redefined down by “VAT”, “tariff”, “border tax”, etc is immaterial.

As already demonstrated, it didn’t take much to change Carrier or GM’s mind to bring jobs back. Although I, and probably most here, are anti-tariff, the promised reductions in regulations will probably FAR outweigh the Trump trade policy mistakes (and I do not count dropping TPP as a mistake, it was a free trade agreement in title only).

China, Mexico, Japan, Europe and more are all devaluing their currencies. We are already in a trade war whether we like it or not. The question is how to manage our way through it and keep US job losses to a minimum.

Comments are closed.