I enjoyed rereading George Stigler’s 1959 piece “Shaw, Webb, and Fabian Socialism,” which I posted about earlier. Here’s another excerpt:

Shaw and Webb discharged a portion, but only a very small portion. of the duties of a responsible proponent of an egalitarian program. Shaw advanced, in fact, three basic arguments for equality of income. The first was simply that there is no other objective basis for distribution:

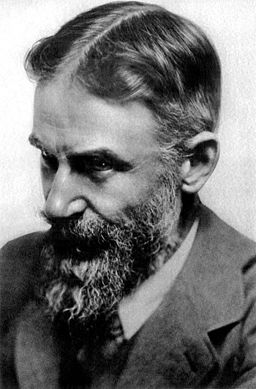

[This is Shaw.] Now . . . suppose you think there should be some other standard applied to men, I ask you not to waste time arguing about it in the abstract, but bring it down to a concrete case at once. Let me take a very obvious case. I am an exceedingly clever man. There can be no question at all in my case that in some ways I am above the average of mankind in talent. You laugh; but I presume you are not laughing at the fact, but only because I do not bore you with the usual modest cough . . . . Now pick out somebody not quite so clever. How much am I to have and how much is he to have? I notice a blank expression on your countenances. You are utterly unable to answer the question . . . .

It is now plain that if you are going to have any inequalities of income, they must be arbitrary inequalities.

[Back to Stigler.] This argument cannot be taken as seriously as it was given. Equality is an unambiguous rule of distribution only when it is applied as unmeaning arithmetic, giving equal sums of income to the day-old baby, the adult worker, and the jailed felon. Conversely, a competitive market does determine, not how much more clever Shaw was than contemporary dramatists, but how much more he produced of what people desired.

This is classic Stigler: insightful and terse.

Sometimes when I discuss equality of income in class, I ask the students if someone in prison for murder should have the same income as the average income of Americans. I have yet to find the student who says yes.

READER COMMENTS

Creon

Jan 6 2017 at 2:30pm

[Comment removed for supplying false email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring your comment privileges. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

Benjamin R Kennedy

Jan 6 2017 at 2:47pm

In the full speech, Shaw makes a market-based argument that unless the poor have some purchasing power, the producers do not have incentives to meet their needs, and instead use productive capacity to meet the needs of the wealthy by making more yachts and jewels and so-forth. This seems like an argument for a subsistence level basic income, not necessarily a call for absolutely equality of income for everyone

john hare

Jan 6 2017 at 2:51pm

And I had to fire an employee recently after he had failed to grasp the basics after two months. Also he couldn’t or wouldn’t follow simple instructions from the experienced people. His value to the company was a negative number.

Should this adult male get the same as one of the guys that has put in a decade or more and can do any job we get with a blueprint and address. There is a reason that some make a multiple of the legal minimum wage and others cannot get jobs at that low rate.

As a southern redneck, I tend to want to explain it with a 2×4 to people that insist we are all the same, and should all receive the same. I have black, brown and women business associates that feel the same way.

MikeP

Jan 6 2017 at 5:24pm

Uh… As much as you can get someone to voluntarily give to you and as much as he can get someone to voluntarily give to him, respectively.

Mr. Shaw, the blank expression is one of dumbfounded astonishment at your stupid question. Maybe you are clever at some things, but you are clearly not clever at all things.

Richard O. Hammer

Jan 6 2017 at 6:11pm

An argument for equality (or toward equalization) of income assumes, unless I am mistaken, that income, when it first appears within human reach, is under control of some social-level decision maker. That decision maker can then decide how to distribute the income without altering the amount of income. Whereas I would suggest that income (the surplus of received value over expended value) usually appears first under the eye and within the reach of the agent who has acted in hope of discovering that income. Such anticipated income created incentive for that agent to act.

Mainstream economic models, which channel thought in fancy abstractions such as the wealth of nations or the supply of a commodity within a market, fail to depict the elements of human action, I would argue. Even Stigler exhibits such crippled channeling of thought above when he says [I paraphrase]:

Stigler’s thought seems to require the “competitive market” as an active agent. But economic calculation starts long prior to anything so fancy as a market. Imagine a primitive society in which the only income is grubs discovered by overturning rocks. In this society there is no nation, commodity, market, or even trade. A grub is seen first by the one who acted to turn over a rock. That one who acted will decide the distribution of that income (grub).

I believe that the model of tabletop critters, which I work to convey, shows some such economic truths more clearly than mainstream economic models.

Floccina

Jan 6 2017 at 9:12pm

Also life is multidimensional if a person has lots of friends or a beautiful wife or a great husband should they have less money? You can not figure it out, so go with MikeP’s solution: As much as you can get someone to voluntarily give to you and as much as he can get someone to voluntarily give to him.

Khodge

Jan 7 2017 at 12:07am

I cannot seem to get past the question: What money? With no incentive to work/produce/trade/profit government is left with nothing to tax and redistribute.

Tom DeMeo

Jan 7 2017 at 8:03pm

“a competitive market does determine, not how much more clever Shaw was than contemporary dramatists, but how much more he produced of what people desired”

“How much someone produces of what people desire” is clearly a major component for why there is inequality. But we always have lots of rules that impede the exchange of value, and the majority of us don’t game those rules in a significant way, while a minority of us clearly do, to great benefit.

“How much someone produces of what people desire” explains inequality. It does not explain the existence of billionaires. That requires some additional explanation.

john hare

Jan 8 2017 at 6:38am

@Tom,

I would say it explains the existence of billionaires quite well. They produce a company(ies) that produces a product. That company is only limited by the market, and the wealth of the billionaire is only limited by the limits of the company(ies). Hiring and nurturing talented individuals is also creating something people want, sometimes.

Tom DeMeo

Jan 8 2017 at 11:02am

@ john hare

Please try a bit harder than that.

Of course, billionaires “produce a company(ies) that produces a product. That company is only limited by the market, and the wealth of the billionaire is only limited by the limits of the company(ies).”

The question is why doesn’t the market work as expected and limit the wealth of those companies? Wouldn’t we expect that natural competition would make becoming a billionaire nearly impossible?

Why do they capture so much more value than any reasonable assessment of the sum of their efforts? The only viable answer is that they are doing more than just meeting the market by producing value. They are also gaming the rules better than the rest of us.

john hare

Jan 8 2017 at 11:29am

@ Tom DeMeo,

I see that I was addressing a different issue than yours. Sorry about that. Gaming the rules as you point out is certainly part of it. Another art is to get in ahead of the pack and stay there using accumulated capital.

I do concrete work including foundations. If I get a backhoe before my competition, I get an edge on the first level competition. Then when some of them take the plunge on a backhoe, I can afford an excavator with an even larger edge on the first level while maintaining an edge on the second level. Lack of capital because I getting the better contracts may prevent them from buying an excavator at all by the time I can get one that is laser and GPS controlled for another level of improvement. At the same time, an edge in one aspect of my business creates the resources to get better equipment for other sections as in formwork, demolition, and finishing.

While all that is going on, I can afford to pay better wages and working conditions to retain better employees with the possibility of attracting others. In my business, quality of employees is key to everything else. Granted that I have seen this mostly from the losing side.

I call it accelerating leverage. It is almost like the joke about the bear chasing the two men. One put on running shoes and said. “I don’t have to outrun the bear, just you.” Once you get ahead, it is very possible to increase the gap. In the decade before the recession, I saw six people go from start up struggle to millionaire, unfortunately I wasn’t one of them.

The ability to leverage advantage in major corporations is correspondingly greater. Reading bios of people like Sam Walton is quite instructive. The leverage is even greater in IT type industries where a single product can be reproduced for very little cost millions of times after the initial development. There is less room for competition in some of these products such that a video game may rake in billions before viable alternatives become available. Even then, many customers may prefer version three of their favorite rather than a perceived inferior product.

I find it very easy to understand the existence of billionaires.

Richard O. Hammer

Jan 8 2017 at 1:44pm

Tom DeMeo asks:

Yes — for people who think in the channels of mainstream microeconomic models — I believe you are right. And I propose that your gotcha shows why so many of the left love those mainstream microeconomic models. Those models offer up “market failures” and thus a role for overseers. Lots of government jobs!

In the better economic model which I advance wealth grows because people discover modes of cooperation which enable those (who participate in those modes) to exploit previously unexploited resources, to create previously nonexistent wealth. In my earlier comment I linked to a description of the tabletop critters. These agents offer one example of use of the broader economic model: The Resource Patterns Model of Life.

Tom DeMeo

Jan 8 2017 at 2:17pm

@john hare

Accelerating leverage produces accelerating profits. That should attract more powerful competition and more investment in that competition.

Your example works at lower incremental levels, but when someone is accumulating capital fast enough to become a billionaire, it breaks down.

You are bootstrapping, and so is your competition. But at some point, if your success reaches a certain threshold, someone with access to more agile capital should recognize your rate of returns and would come in and outperform you, even though they are just copying you.

The bottom line is that you either believe in the way markets work or you don’t. At some point, holding onto windfall profits becomes more of a political problem. Otherwise, market competition would continue to ratchet up as you continued to succeed, until you reached the limits of your personal abilities, well short of a billion dollars.

Johnhare

Jan 8 2017 at 2:32pm

So why should investment no longer perform as wealth approaches a billion dollars?

MikeP

Jan 8 2017 at 5:00pm

Otherwise, market competition would continue to ratchet up as you continued to succeed, until you reached the limits of your personal abilities, well short of a billion dollars.

You are seriously underappreciating the contribution of luck.

Take 16 people with 200 million dollars. Have each of them use 150 million to ride roulette colors 4 times. One of them will be a billionaire at the end. What is the political problem?

To be sure, most capital accumulation is not as obviously ruled by luck. Nonetheless, the founders and investors in Friendster and MySpace are not billionaires, while the founders and investors in Facebook are. If Facebook were first and MySpace were third, then MySpace would have generated the billionaires.

Very few billionaires accumulate their way to it from diverse gains over dozens of investments. Most of them have one or a very few big wins. For those big wins, by the time the opportunity is recognized by others, the gains have already been distributed. No amount of economic competition will redistribute those gains.

You might think it’s not particularly fair that certain technologies admit extreme leverage or certain industries exhibit high network effects, but they do. And it is true that there are plenty of examples of billionaires generated by government protected or directed companies or industries. But billionaires qua billionaires are not an indication that market competition does not exist.

Johnhare

Jan 9 2017 at 1:12am

So why should investment no longer perform as wealth approaches a billion dollars?

d clark

Jan 10 2017 at 12:45am

[Comment removed for supplying false email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment and your comment privileges. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

d clark

Jan 10 2017 at 9:45pm

Ed., Pls delete the post with my email addresses.

[d clark: You are going to have to respond to our email to you in order to validate your email address. If you can’t remember which email address you use, you won’t be able to post comments here. Please check all your email addresses and use the email address from which you’ve responded in your future comments.–Econlib Ed.]

Comments are closed.