George Selgin sent me a 2000 JMCB paper by David Reifschneider and John C. Williams, who were both at the Fed:

To reduce the effects of this phenomenon, in our simulations we incorporate a notional upward adjustment to the inflation target of the policy rule to offset the aver- age effect of the positive deviations to the rule that occur when interest rates fall to zero. In this way, policy attains its inflation goal on average. As shown in the next section, this bias adjustment is a nonlinear function of the target rate of inflation, among other factors. We use this form of adjustment because of its simplicity and transparency, not because it is optimal. Intuitively, a better strategy would be to employ a conditional adjustment to the policy rule that adjusts the funds rate down immediately before or after episodes of zero interest rates; in this way offsetting movements in the funds rate would be more likely to occur when economic activity is still weak and inflation low. We consider just such a strategy in section 5 of the paper. (Emphasis added)

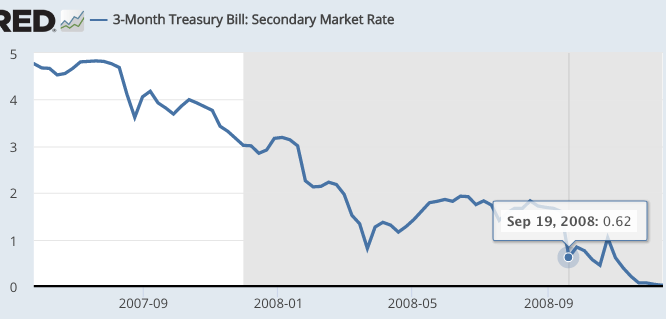

The zero bound need not be a big problem for central banks if they utilize level targeting. Unfortunately, most central banks use growth rate targeting, where policy becomes less effective at the zero bound. In that case, the optimal policy is to make policy more expansionary than otherwise when you are close to hitting the zero bound. This reduces the risk of a zero bound problem. Unfortunately, the Fed did exactly the opposite during late 2008:

Notice that the 3-month T-bill yield had fallen to 0.62% by September 19, 2008. At that time, the Fed funds target was still way up at 2.0%. Markets were signaling (correctly) that much lower rates were on the way. The Fed should have reacted to this warning by cutting their fed funds target in September, but they did not do so.

In the past I’ve criticized Fed policy for being inappropriately tight in September 2008. Given that both employment and inflation (market) forecasts were well below the Fed’s target, they should have eased policy. That argument did not even take account of the optimal strategy discussed by Reifschneider and Williams. In other words, money was already far too tight even ignoring the zero lower bound issue. But now we see that things were actually even worse–monetary policy should have been more expansionary than would normally have been appropriate given the level of inflation and employment forecasts. That makes the mistakes of late 2008 even more unforgivable.

The Fed was acting as if there was no threat at all of hitting the zero bound, when in fact the markets were signaling that policy was about to smash into the zero bound. What was the Fed thinking? Where was the back up plan for the zero bound? We now know the Fed had no back up plan, but in that case why didn’t they do everything possible to avoid the zero bound?

If there is no guardrail on the highway, and your steering is not working very well, then don’t drive right on the edge of the cliff!

PS: Speaking of George Selgin, I strongly recommend his recent piece on interest on reserves (as well as his earlier posts). George made me realize that there are actually two problems with IOR, one demand side and one supply side. I knew that the imposition of IOR in October 2008 reduced aggregate demand, and at the worst possible time. Selgin points out that the policy has also reduced aggregate supply. It causes bank reserves to make up a much bigger share of bank balance sheets than otherwise, and this crowds out lending to the private sector. Selgin notes that this is an example of financial repression. (This explanation oversimplifies his post; read the whole thing.)

This David Beckworth post on IOR and bank reserves is also quite informative. I agree with his suggestion that IOR be brought down to the level of market interest rates. (Indeed I’d prefer IOR be set well under market rates.)

READER COMMENTS

Benoit Essiambre

Oct 29 2017 at 5:44pm

>Selgin points out that the policy has also reduced aggregate supply. It causes bank reserves to make up a much bigger share of bank balance sheets than otherwise, and this crowds out lending to the private sector.

I didn’t realize this was considered supply side. I thought this was just the investment component of the demand side. I thought supply side was more about real world constraints and extractions through taxes.

As I mentioned recently, it seems to me that this tweaking of financing for new capital investment is the most important monetary transmission channel not just regarding IOR but with all central bank interest rate changes. What distinction am I missing?

Would you then say that my beliefs could be labeled as central banks most directly effecting the supply side and only indirectly the demand side? I’m confused about the language (It’s already confusing enough that my profession calls “cost of financing”, “cost of capital”).

Kevin Erdmann

Oct 29 2017 at 7:42pm

Excess reserves starting piling up immediately after the September Fed meeting, weeks before IOR was implemented, suggesting that the neutral rate was already below zero immediately after the Fed policy announcement, even before they implemented IOR.

Robert Simmons

Oct 30 2017 at 8:57am

Shouldn’t we differentiate between interest on required and excess reserves? Required reserves should be paid interest at market rates; excess reserves should be paid no more than that, probably less, maybe zero.

George Selgin

Oct 30 2017 at 11:32am

Kevin Erdman writes: “Excess reserves starting piling up immediately after the September Fed meeting, weeks before IOR was implemented, suggesting that the neutral rate was already below zero immediately after the Fed policy announcement, even before they implemented IOR.”

I don’t think that’s correct. The initial accumulation of reserves reflected high perceived counterparty risk in the immediate wake of Lehman’s failure, as reflected in the LIBOR spread. That risk soon abated. From then on the driving force behind excess reserve accumulation was IOER, which created an above-zero lower bound. Comparable short-term rates remained above zero though below the IOER rate. If you look at volume of interbank loans, there is only a modest decline until IOER kicks in.

Kevin Erdmann

Oct 30 2017 at 2:09pm

Thanks for the input, George.

It is strange that the effective fed funds rate was still above zero while that happened, and I suppose your explanation explains that gap.

Do you have any links to descriptions of the details of that period that would provide additional information regarding your comment?

Scott Sumner

Oct 30 2017 at 5:10pm

Benoit, This makes the financial system less efficient, and in that sense is a supply-side effect.

The demand side effect of IOR is to boost the demand for base money, which is contractionary.

Thus IOR has both supply and demand side effects.

The financial system (credit) is not an important part of the transmission mechanism, as AD is all about the supply and demand for base money.

Kevin, I agree, and indeed some estimates (by Curdia) show it turning negative in early 2008.

Robert, I agree.

George, Yes, but given the speed at which NGDP declined in the second half of 2008, I suspect the natural rate was already negative.

Benoit Essiambre

Oct 30 2017 at 8:10pm

Ok thanks for taking time to educate me. I was thinking more in terms of the flip side, demand for everything but money, where it seems to me, that demand for new capital would be a crucial component in monetary transmission, mainly because new money starts in the banking system and lending.

Though I kind of get that if knowledge of increased base money spreads quickly enough that velocity is going to go up everywhere making the original channel less relevant. Information transmission is still somewhat of a sticking point for me however. Does it really jump economy wide that fast?

Joosef

Oct 31 2017 at 3:54am

Scott, you might find it interesting that Bullard critically takes on Reifschneider–Williams directly in the December 2008 FOMC meeting, pages 48-49 (though he admits that by then the point is already moot): https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/FOMC20081216meeting.pdf

“I do not find the Reifschneider–Williams paper, which I know carries some weight around here, very compelling, so let me give the brief reasons behind that. For one thing, you are taking a model and you are extrapolating far outside the experience on which the model is based. That might be a first pass, but that is probably not a good way to make policy, and I wouldn’t base policy on something like that. There are also important nonlinearities. This whole debate is about nonlinearities as you get to the zero bound, and in my view, they are not taken into account appropriately in this analysis. You have households and businesses that are going to understand very well that there is a zero bound. It has been widely discussed for the past year. They are going to take this into account when they are making their decisions, so you have to incorporate that into the analysis. That is a tall order—there are papers around that try to do that, and many other assumptions have to go into that.

The third thing I think is important is that, in other contexts, gradualism or policy inertia is actually celebrated as an important part of a successful, optimal monetary policy. Mike Woodford, in particular, has papers on optimal monetary policy inertia, and many others have worked on it. In those papers, it is all about making your actions gradual and making sure that they convey some benefit to the equilibrium that you will get. All of a sudden, in this particular analysis, when you are facing a zero bound, that goes out the window, and I don’t think that it is taken into account appropriately in the analysis. Also, it is thrown out the window exactly at a time when you might think that the inertia and the gradualism are most important, which would be in time of crisis when you want to steer the ship in a steady way. So I think that we have a long way to go to understand exactly how to behave near a zero bound, and I would not make policy based on that particular analysis or the subsequent work. But as I stated at the beginning, I think it is a moot point anyway because the effective fed funds rate is trading near zero. We are there. We have arrived.”

Brian Donohue

Oct 31 2017 at 8:20pm

Another very good post Scott.

I remember asking several months ago about when and if the Fed should end above-market IOER and you blew me off.

I get it. I’m just an Internet nobody. Glad to see you’re getting there eventually.

Brian Donohue

Oct 31 2017 at 8:22pm

Another very good post Scott.

I remember asking several months ago about when and if the Fed should end above-market IOER and you blew me off.

I get it. I’m just an Internet nobody. Glad to see you’re getting there eventually.

Matthew Waters

Oct 31 2017 at 8:41pm

I read Seglin’s post and I’m a bit confused.

For example, it says that excess reserves put taxpayers on the hook for risky government spending. That doesn’t make sense to me. Taxpayers become at risk when the spending happens, not when the bond to pay for that spending is bought by the Fed.

Neither does IOER necessarily offset private bank loans which would otherwise happen. The private investment was crowded out when the Treasury issued the bonds, not when the Fed bought them. The Fed will offset the public investment one way or another under a successful monetary policy regime.

So I think the post overstates the effects of IOR on the supply-side. On the demand-side, it forces the Fed to make more OMO’s than without IOR. That’s not *inherently* a bad thing. In practice, it was bad for the demand-side because the Fed did NOT offset IOR in 2008 with enough OMO’s.

On the supply-side, IOR probably hurts because it creates more financial transactions than otherwise would happen. The system of primary dealers, their commissions, etc. is still kind of a mystery to me. At best, putting these huge orders through primary dealers fueled conspiracy theories. At worst, the primary dealers earn some rent from arbitrary government action.

Comments are closed.