Last week I attended the Cato Monetary conference in Washington. Jim Dorn always does a good job of finding interesting speakers.

I couldn’t help contrasting the event with the Peterson Institute conference that I attended last month. At the Peterson Institute, most speakers correctly noted that insufficient AD was a key problem over the past decade, but also argued (wrongly, in my view) that monetary stimulus was relatively ineffective at the zero bound. At Cato it was almost the exact opposite. I don’t recall anyone doubting the effectiveness of monetary policy (I attended 3 of the 4 panels), but there was almost no concern about insufficient nominal spending. Indeed a number of speakers seemed worried that policy was too expansionary.

This makes me feel really good about the prospects for market monetarism. Both logic and facts are overwhelming on our side. It seems absurd to claim a fiat money central bank could not debase its currency. Are the Zimbabweans really that much more talented than we are? And when countries like Japan have changed policy the yen has fallen sharply, even at the zero bound. That doesn’t happen in the Keynesian model. As for the level of AD, during most of the past decade both inflation and employment have been well below the Fed’s targets. It’s the (conservative) opponents of monetary stimulus who have a difficult argument to make, not us.

This recent article gives a good sense of the weakness of the arguments of our opponents:

TOKYO (Reuters) – Premier Shinzo Abe’s victory in last month’s election may make it difficult for the Bank of Japan to dial back its radical stimulus next year despite the rising cost of prolonged monetary easing, former BOJ board member Sayuri Shirai said on Friday. . . .

Shirai said the BOJ should start withdrawing stimulus by hiking its yield target and slowing asset purchases next year, given the rising cost and diminishing returns of its policy.

“When the economy is in good shape like now, the BOJ needs to normalise monetary policy so it has the tools available to fight the next recession,” Shirai told Reuters.

“But the election result has made that difficult,” she said.

Raising the BOJ’s 10-year government bond yield target could trigger an unwelcome yen rise by narrowing the interest rate differentials between Japan and the United States, Shirai said.

This quote exhibits a basic lack of understanding of monetary economics. The speaker implies that tightening monetary policy gives the BOJ more “tools” to fight the next recession, whereas the exact opposite is true. When the BOJ tightens monetary policy the natural rate of interest falls. The speaker presumably believes that what matters is the gap between the actual rate of interest and zero, whereas what really matters is the gap between the natural rate of interest and zero. When the BOJ raises the actual interest rate with a tight money policy, the natural interest rate falls.

If Shirai were correct, then the Fed could have raised interest rates to 20% in 2008, giving them lots of “tools” to later cut rates and spur the economy when the recession got severe. But that’s about as effective as trying to pick yourself up by your bootstraps. This is why I insist that people appointed to the Fed should be experts on monetary economics. I don’t care about credential—it makes no difference if they have a PhD—but they need to understand the basic principles of monetary economics.

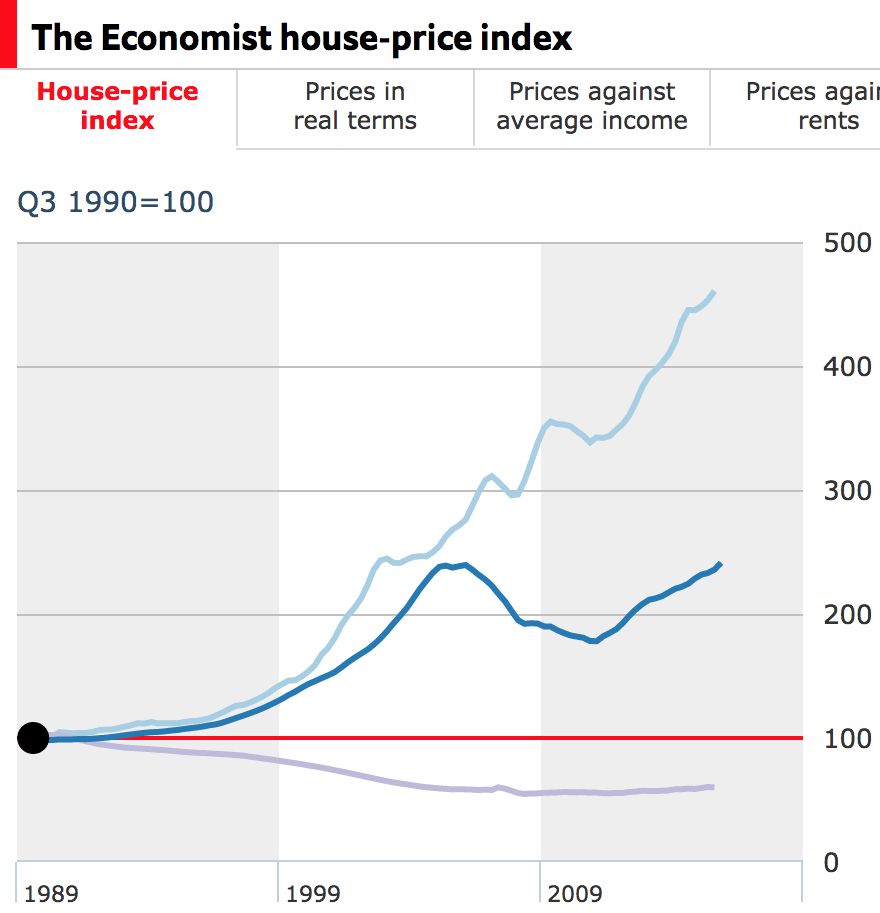

Does Japan need higher interest rates to pop asset prices bubbles? Consider the Japanese stock market, which is about 40% below the peak value in 1991, while the US market has risen almost 10-fold. Or take housing, where prices in Japan are down about 40% since 1990 (lavender line), while they have risen 140% in the US (blue) and 360% in Australia (light blue).

Australia’s had the highest interest rates over that period (among developed countries), and Japan has had the lowest. So no, rapid asset price increases are not caused by low interest rates, indeed asset prices tend to rise more rapidly in countries with very high nominal interest rates. Japan doesn’t have to worry about asset price bubbles.

Japan would benefit from higher nominal interest rates, but only if brought about by a more expansionary monetary policy.

PS. I should emphasize that there was plenty that I agreed with at the Cato conference. A number of speakers were critical of the war on cash (as am I), and Charles Calomiris was skeptical of the view that China was a currency manipulator.

PPS. David Beckworth presented me with a coffee mug.

Market monetarism is right on target to becoming the dominant view in macroeconomics; just give us another 10 or 20 years.

READER COMMENTS

Kevin Erdmann

Nov 18 2017 at 9:44pm

“If Shirai were correct, then the Fed could have raised interest rates to 20% in 2008, giving them lots of “tools” to later cut rates and spur the economy when the recession got severe.”

Remove a “0” and this was the exact Fed policy and reasoning.

Right Wing House Music

Nov 19 2017 at 12:02am

I’m sure Professor Sumner has explained this dozens of times within the thousands of his blog posts, but how, exactly, do market monetarists believe that monetary policy can beat the zero lower bound?

If businesses won’t borrow money from the bank, what is the point of giving the banks more money to lend?

If low consumer spending ensures that the loans never get paid back, what is the point of making loans more available?

Scott Sumner

Nov 19 2017 at 1:10am

Kevin, I don’t think that was the Fed’s reasoning. At least not Bernanke’s.

Right Wing. The point of monetary stimulus is not to encourage more lending, it’s to encourage more NGDP. You do this by increasing the supply of base money more rapidly than the demand is increasing.

There is no need to involve the banking system at all—just buy assets.

Kevin Erdmann

Nov 19 2017 at 2:57am

Scott,

You’re right.

I was thinking of Bernanke’s reason for implementing IOR to keep the rate at 2%. But, that wasn’t really to leave more room for future rate cuts. It was because the emergency lending they were engaged in – at the time – was pushing rates down below their 2% target and he wanted to stop the decline.

Looking back at the Sept. 2008 transcript to see what the others were saying, I was reminded that the rest of the committee wasn’t worried about leaving room for cuts, because several of them were ready to raise rates. They thought the next rate move was higher. So, that definitely wasn’t the thinking of the rest of the committee.

Kevin Erdmann

Nov 19 2017 at 3:12am

BTW, I took a quick look at the October and December meetings, and there was discussion about this at those meetings. Some members wanted to “keep dry powder”, but luckily the doves won the day on both occasions.

Thaomas

Nov 19 2017 at 9:31am

I think Scott is correct in his view on NGDP targeting (although I think that PL targeting + unemployment minimization is more congruent with the Def’s actual mandate).

But then he spends his entire column arguing against the “monetary policy is ineffective” argument when that is not what prevented the Fed from being more stimulative in 2008-17.

It was not the befuddled economic profession that brought pressure on the Fed to adopt an inflation rate ceiling, to abandon successive rounds of QE, to raise ST interest rates in 2016-17; it was the people in the CATO Institute orbit, not the Peterson Institute orbit.

Scott Sumner

Nov 19 2017 at 11:44am

Thaomas, You said:

“But then he spends his entire column arguing against the “monetary policy is ineffective” argument when that is not what prevented the Fed from being more stimulative in 2008-17.”

Actually I think that was part of the problem. If Obama had understood that monetary policy was effective at zero rates, he probably would not have appointed so many hawks to the Fed.

Alec Fahrin

Nov 19 2017 at 12:48pm

Scott,

Why do you say thay Obama appointed many hawks to the Fed? I wouldn’t call them doves, but compared to those people I consider monetary “hawks” in the economic community I think most of Obama’s picks were moderates.

Remember that Obama had to work with a Republican Senate from January 2011 on, and during this time the Republicans did everything they could to obstruct him. Screaming about impending inflationary doom was the main tactic.

Mark

Nov 19 2017 at 3:34pm

I suspect that in the US during the financial crisis, the belief among many (both in government and academic economics) that only fiscal policy could be effective – and the desire to prove it – also had a bad effect on monetary policy.

Mark

Nov 19 2017 at 3:41pm

Thaomas,

I don’t know who carried the torch during the crisis, but currently Cato’s chief monetary expert is George Selgin, who favors NGDP targeting.

Comments are closed.