Many people, including rationally ignorant voters, ignore the poor state of the US government’s finances. The Table below gives some numbers, extracted from the last budget of the US government. Politicians should be aware of the problem, but their self-interest is to kick the can down the future and compete for the perks of power by promising voters new programs, transfers, and tax cuts (see James Buchanan and Richard Wagner’s 1977 book Democracy in Deficit: The Political Legacy of Lord Keynes).

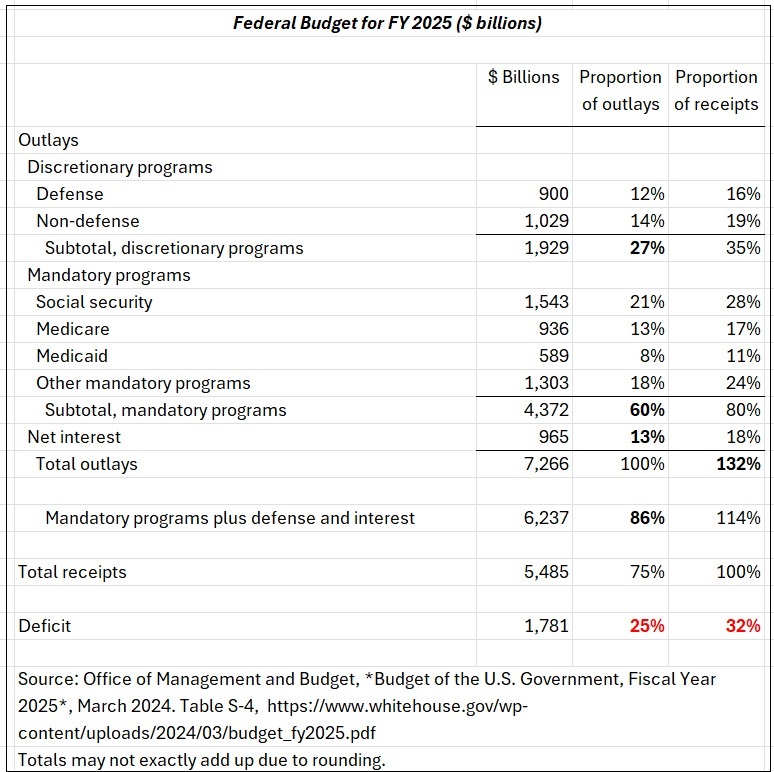

If Congress appropriations follow the budget of March 2024, outlays (spending) for FY 2025 (October 1, 2024 to September 30, 2025) will reach $7.3 trillion compared with forecasted receipts (revenues) of $5.5 trillion. A deficit of $1.8 trillion will result. Next year, then, the federal deficit is set to equal 25% of spending and 32% of receipts (the figures in red on my Table).

This level of annual deficit has become quite typical. Federal spending reached $1 trillion in 2019, peaked at $3.1 trillion in 2020 and, after the epidemic, receded to an average of $1.9 trillion from 2021 to 2024.

The problem is not caused by annual emergencies or enthusiasm, nor by random “government waste.” Sixty percent of federal spending is called mandatory, for it is made of large programs mandated by standing laws and regulations and not subject to annual appropriations by Congress. The mandatory programs are essentially Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. The “other” category mainly comprises income security programs such as unemployment compensation, nutrition assistance programs, or Supplemental Security Income.

The part of federal spending called discretionary (27% of spending) includes $900 billion for defense plus annual appropriations by Congress for all other purposes.

To these two broad categories of spending must be added nearly $1 trillion (13% of spending) for interest payments on the public debt. Interest payments diminish when the rate of interest decreases, but increase with the growing level of debt.

Adding to mandatory programs the outlays for defense and interest on the public debt, which are not easily or readily compressible either, we get 86% of total outlays. Thus, only 14% of federal spending is compressible or “discretionary” in this sense. Eliminating the annual deficit without increasing taxes would require the elimination of all these “discretionary” outlays plus an 11% reduction in “non-compressible” expenditures (mandatory programs, defense, and interest on the public debt).

Since 1961, the OMB’s historical budget tables (see Table 1.1) show a surplus in only five years: 1969, and 1998 to 2001. The problem is obviously not a function of which political party is in power. Chronic deficits explain why the federal debt held by the public is predicted to reach $30 trillion at the end of (calendar year) 2025, more than twice the $14.2 trillion at the end of President Barack Obama’s second term (see Table 7.1).

The public debt is a time bomb that will have to be defused or will explode at some point. If large increases in taxes or default on the public debt are to be avoided, a fundamental reassessment of the federal government’s functions and scope will be needed.

******************************

The government sinking in debt

READER COMMENTS

Jose Pablo

Sep 10 2024 at 9:21pm

I don’t really get all the rage with the “deficit”. The “deficit” is good … well, at least better than the alternative.

There are two alternatives to the deficit:

* Raising more taxes: How can this be better? How can taking money from people by force be better than getting it in a voluntary exchange? I think this is the first time I see you defending such a thing!. Are you moving to the dark side?

* Spending less: I guess this is the alternative you really defend. But if this is the case then say so!. Don’t use the “deficit” as the bad guy. The deficit is better than more taxes. By all means. Morally (you taught me that) and financially (after all taxes have a higher opportunity cost than government debt).

If you don’t like government spending, say it. But let the deficit alone. Be careful, the government could hear you and raise more taxes. By force. I do prefer the government asking for voluntary money in the financial markets instead of knocking on my door and taking by force my car, my trip to Europe, my good wine … all the things I wouldn’t have if the government increases taxes.

Maybe you believe that the increase in taxes will make voters force the government to reduce spending. I very much doubt so. That is naïve. It is much more likely that, in that scenario, voters will engage in a ferocious fight (even more) to make “others” (the rich, our grandchildren, foreign producers of goods … others!) pay even more taxes and keep the spending growing.

The alternative to the deficit is the government thieves coming after your money … even more than now.

Craig

Sep 10 2024 at 9:52pm

“The alternative to the deficit is the government thieves coming after your money … even more than now.”

Just like Nero debasing the denarius, the regime will tax your buying power. They WILL choose inflation because its the culture and then they’ll blame the grocery store when Cheez-Its are $50 a box.

Jim Glass

Sep 11 2024 at 2:29am

Or not. It’s not so easy to inflate away debt when it is financing (1) real goods and services (Medicare, etc.) and (2) inflation indexed obligations, especially to seniors (Social Security, unfinanced federal pensions, etc.) Seniors are the most activist and potent interest group there is. Russia has a very bad pension-cost problem. Putin tried to cut it a bit, his seniors got angry an he backed down fast. He’ll fight a bloody war with Ukraine, NATO and the entire West — but won’t take on his pensioners!

Also, our history suggests otherwise. Social Security has already gone broke once, in 1983. For some reason, people don’t remember. The result was a tax increase on payroll, benefit cuts for the then young, and a means test on benefits (carefully disguised as income tax — except the proceeds go back to the SSA effectively reducing one’s net benefit in accord with income, and as this is not inflation-indexed it is still reducing benefits by an ever greater amount every year.) It worked. Nobody even remembers. A precedent to follow on the larger scale.

Plus … a good number of European countries are in a lot worse shape than we are, and are going to go off the cliff first. We can watch and learn.

Craig

Sep 11 2024 at 10:10am

Post WW2 they inflated the debt:GDP down but of course they slashed the spending because the war was over. Nowadays they politically cannot cut spending, so they won’t, the checks must go out and while I do believe they are gaslighting the American people about the cause of inflation, ultimately I also think they might be gaslighting themselves, ie that they don’t think it will actually cause the inflation…..suggestions for price controls ensue.

Jim Glass

Sep 11 2024 at 6:10pm

Sure thing. BUT…

Medicare is the #1 driver of the coming fiscal ‘challenges’. and its enabling legislation has in fact included price controls for many years now. However, every time the controls are about to hit, guess what happens. They are suspended, lifted, re-written … never take effect.

The reason is price control econ 101: funds paid go down, quantity supplied goes down. That creates two screeching huge and powerful political interest groups: (A) the entire health care industry — from receptionists through techs and nurses to brain surgeons — which runs on revenue from Medicare, really not wanting to suffer income, wage and job cuts, and (B) seniors, really not willing to suffer reduced, slower, lower-quality medical care. Which puts the kibosh on price controls.

That leaves the remedies that were actually applied to re-organize Social Security in 1983: (1) current tax increase, & (2) current benefit cuts to the extent politically possible, e.g. though means testing (why should millionaires get health care paid for from the payroll taxes of fast-food workers?), & (3) significant benefit cuts for much younger persons who don’t perceive any personal loss coming at them for a long while and who have time to make alternative arrangements.

“All this has happened before, and it will all happen again.”

MarkW

Sep 13 2024 at 9:11am

” It’s not so easy to inflate away debt”

Not least because attempting to do so will raise borrowing costs and make the deficit worse (as has just been clearly demonstrated).

Kevin

Sep 11 2024 at 1:44am

Of course spend less, but are you really advocating for keeping the deficit the SAME? Spend less, and decrease the deficit. We almost certainly have more horrific inflation in our future.

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 11 2024 at 11:43am

Jose: You wrote:

Not yet! My argument was purely positive, not normative. I did not mean to suggest that taxing more was desirable–although I do fear that European levels of taxation will turn out to be the solution that politicians pursue, especially if they relieve themselves of some political competition.

Craig

Sep 10 2024 at 10:06pm

“Many people, including irrationally exuberant bond-buyers, ignore the poor state of the US government’s finances.” <–FTFY

Interest now greater than defense budget.

Jose Pablo

Sep 10 2024 at 11:07pm

Government debt interest is the cheapest way of financing the spending. Taxes sure have a higher opportunity cost.

If you buy your house with debt you will pay “interests”. How much money you pay in interest says nothing about whether or not this what the right decision. For that, you need to know the expected returns of the best alternative use of your money. If these returns are higher than what you pay in interest then it was a great decision. If they are lower it was a bad decision.

Same case with financing the spending with debt vs taxes. The key is the “opportunity cost” of taxes. Unfortunately, interest payments are seen and the opportunity cost of taxes is not seen. That doesn’t make it any less relevant.

Craig

Sep 11 2024 at 1:19pm

Your analysis does suffer from a flaw though inasmuch as it presumes that the spending is going to happen, which honestly under the totality of the circumstances isn’t a bad assumption. However, the problem IS the SPENDING. It is the SPENDING that makes a claim to the goods and services that we create with our scarce time, labor and capital.

Matthias

Sep 11 2024 at 8:40pm

Many foreigners, including the Chinese, are willing to use their scarce labour and resources in return for American spending.

You could tap them more, eg by lowering tariffs.

Jose Pablo

Sep 10 2024 at 10:56pm

An interesting question would be: what should be the “right” amount of deficit?

The “worst that got on top” and traveled to Washington to fool around (aka politicians) have no way of knowing. They lack, for the most part, the financial knowledge and they definitely lack the right set of incentives.

As always, individuals should know better. The government only have to properly frame the question and provide the right incentives.

Here is how it could be done. The ultimate “optimal deficit discovery” strategy:

The Government decides the level of spending (for me this is the main problem, but since people prefer to focus on deficits …). Let’s say $100 for this year.

Taxes are assigned to every taxpayer (legal entities or individuals) for an amount that, on aggregate, equals the level of spending ($100).

[Now, this doesn’t require any change in the tax code. It would take forever to agree on that (fortunately!). We keep the existing tax code. But if the amount of taxes raised with this tax code is $75 (equivalent to the figure in your post), we multiply this notional amount by 1.33]

Every single taxpayer now can decide on two courses of action:

Send that money (their taxes according to the current tax code * 1.33) to the IRS

Incur a debt with the government for this very same amount.

[The government will offer different terms with different interest rates for each term]

The Treasury would then go to the financial markets and would raise an amount that matches the total debt “decided” by the taxpayers, with a term structure similar to that, on aggregate, of the individual taxpayers.

[the interest rates for this emission will be passed through to taxpayers]

The role of the government will only be servicing this debt. Collecting payments from the taxpayers and using them to pay the debtholders (plus a small fee for the cost of this servicing).

The rational individual taxpayers faced with the choice between sending money to the IRS or incurring a debt with the government will look at the opportunity cost of the money they have to send to the IRS (either as foregone consumption or as an actual investment in different endeavors). They will then compare this opportunity cost with the interest rates of government debt) and will decide what is most convenient to him “individually” (for me incurring debt can make sense since I have ways of investing my money with returns higher than the cost of the government debt. For my neighbor the opposite can be true).

The “optimal level of deficit” will be the one “discovered” by this mechanism. Honestly, I have no way of knowing if this is going to be higher, lower, or the same as the actual level. But in the absence of this mechanism stating that the deficit is “too high” is a case of “you say so and I say so”.

I am sure you will appreciate the “beauty” of taking the decision about the level of deficit out of the politicians’ hands and letting the individual decide. The “collective” decision will then be the mere aggregate of individual decisions.

As it should always be!

Jim Glass

Sep 11 2024 at 2:07am

You are theorizing as if the politicians aren’t already giving the individuals exactly what they want — indeed, as if they aren’t forced by all the individuals to do so to get elected. What happens to the politician who says, “I know, let’s just CUT spending on Medicare and Social Security and … ” Stop right there! That’s an EX-politician.

Individuals *always* want: “Gimme now! I’ll pay later, sometime, maybe.” That’s what keeps the credit card industry going, and the credit repair industry, and all the bankruptcy lawyers and courts, and the massive semi-scam college loan industry, and the “forgive our college loans” political movement…

And it is why, in our most divisive political era since 1859, the one thing both political parties completely agree upon is: More Debt Spending! Because it is what ALL the individuals who elect them want.

Jose Pablo

Sep 11 2024 at 11:25am

giving the individuals exactly what they want

This is not what politicians do. It is impossible, to start with, because every single individual wants a different thing. Even Scott wants deficits, just smaller.

Moving from a system that gives everyone something in line with “what a majority of voters seem to want” to a system that gives every different individual exactly what this precise individual wants (in my example in terms of deficit) is a huge development. And should be welcomed!

Scott Sumner

Sep 11 2024 at 12:31pm

“Send that money (their taxes according to the current tax code * 1.33) to the IRS

Incur a debt with the government for this very same amount.”

We already have essentially that system in place. If I have a tax bill for $10,000, I can send a check for $10,000 to the government, or I can borrow $10,000 from a bank and send the money to the government.

I prefer to have people borrow from banks, as I don’t trust the government to correctly identify credit risk.

Jose Pablo

Sep 11 2024 at 12:56pm

I can borrow $10,000 from a bank and send the money to the government.

Yes, precisely. And the conditions of this loan (term, interest rates, and collateral required) are way worse than the conditions on government debt. Which would make borrowing from a bank a worse solution for taxpayers (compared to borrowing from government debtholders). Deficit = access to government debt terms for the individuals.

I don’t trust the government to correctly identify credit risk.

And that’s precisely what the government does (maybe inadvertently) when deciding how much money you have to pay in taxes. People with a higher tax bill have in general better credit risk. I am pretty sure that you will find a great positive correlation between the size of individual tax bills and credit scorings.

[And you could always have an independent agency, kind of a FED, performing this credit scoring when a taxpayer wants to borrow. It doesn’t change the thought experiment and would only increase credibility in the government debtholders’ eyes]

Scott Sumner

Sep 11 2024 at 9:34pm

I have no idea what you are talking about. Your proposal would essentially provide no strings attached loans to the public at the borrowing rate of the Treasury. What could go wrong?

Jose Pablo

Sep 12 2024 at 11:44am

Your proposal would essentially provide no strings attached loans to the public at the borrowing rate of the Treasury.

Yes! … up to a maximum amount equal to your “true tax liability” (in my example the tax liability coming out of your tax return * 1.33) for that year.

My point is that this is precisely what government debtholders are (very happily) ultimately doing right now: providing American taxpayers with no-strings-attached loans. The amount of these loans equals the deficit. And the government debtholders know that the Treasury doesn’t produce any income. The Treasury can only force taxpayers to send money its way under the threat of harsh punishment. The Treasury will keep this ability to force individual “not-yet-paid-taxes-debtholders” in my proposal.

The national debt is an American individual taxpayer’s liability (and the debtholders know that). Now there isn’t a way of clearly assigning this collective liability individually. It is undefined and messy. But it is an individual taxpayer liability nevertheless. I don’t see how making clear which individual truly owns this liability can make it, in any way, worse.

In any case, the discussion is not about the mechanics of the proposal or its political feasibility. My point is that this is the way of knowing what is the optimal level of sovereign debt. Not the opinion of an expert (no matter how educated) and much less the decision of a rat-pack of representatives sitting in Washington with the wrong incentives.

Building on your (very good) last post, this is how we ask ourselves: “Do taxpayers prefer more or less deficit?“. This system will provide us with their “revealed preference”.

And with the right incentives in place. They can go to jail if they don’t honor their “not-yet-paid-tax-debt” with the government (the same way that they can go to jail now if they don’t comply with their tax obligations … in Texas, you could even legislate that taxpayers can be sentenced to death if they don’t pay back their “tax-loans”)

Now, I am agnostic about what the answer could be. My point is that this is the way of asking. In my opinion, the “rational taxpayer” will ask for these “non-string attached loans at Treasury rates” if his/her opportunity cost is lower than the government debt interest rate.

This could, very easily, result in the rational American taxpayers demanding more deficit, not less

What could go wrong?

I don’t see what could go wrong. But if you can be more specific I am more than happy to discuss your worries

Scott Sumner

Sep 10 2024 at 11:02pm

The debt was at least somewhat sustainable until the late 2010s, when it went completely off the rails. That’s when I started to seriously worry about the issue. The Covid deficits were even bigger, but the late 2010s were already indicating that the path was unsustainable.

Jose Pablo

Sep 10 2024 at 11:24pm

If the tax burden had been higher since 2010 (higher enough to keep the debt “sustainable”, according to your criteria), how do you know we would be in a “better place” now?

It could very well be the case, but reaching this conclusion requires making some assumptions about the opportunity cost of “taxes” to taxpayers (I finance my tax payments at rates way worse than government debt), about the utility they get from their tax money (I finance my spending at rates way worse than government debt) and about what would debt holders do with their money in the case of a smaller government debt market.

In a scenario with more “sustainable” deficits since 2010, private investments could be lower, personal spending could be lower and debtholders could be financing personal spending and private investments somewhere else (in Europe or China). Maybe you are right and this would be “better” but this is far from obvious to me.

Jose Pablo

Sep 10 2024 at 11:30pm

I meant:

* … the opportunity cost of “taxes” to taxpayers (I could invest my tax payments with returns way better than government debt)

JoeF

Sep 13 2024 at 2:53pm

“The debt was at least somewhat sustainable until the late 2010s, when it went completely off the rails.”

I don’t see that (if I am looking at the right thing). Looking here (https://www.statista.com/chart/28393/us-public-debt/) it looks like a pretty standard exponential curve (except for the Covid discontinuity). The late 2010s actually look to have less slope than the early 2010s.

Jim Glass

Sep 11 2024 at 12:56am

You are seriously understating the problem. The Treasury itself says that for 2023 the real number was $3.4 trillion using the accrual accounting standards that the federal government requires everyone except itself to use…

The “deficit” number you are citing is calculated using cash accounting, which is permitted by the federal government only for small business like candy stands, and the federal government itself. In 2023 that was “only” $1.7 trillion, just half the real full incurred unfunded liability.

For the life of me I don’t understand why nobody ever cites the TREASURY on this. It’s not like The Financial Report of the United States Government is some crank source with an agenda. There aren’t many deficit hawks left, but any who are should be *all over* this!

Jim Glass

Sep 11 2024 at 1:40am

And speaking of agendas … let’s *not* go back to 1977 to try to bogeyman Keynes as being the villain in all this. He has *nothing* to do with it….

John Maynard favored *paid for* public works and government investment, not deficits. Upon meeting some of his New Deal economist acolytes he said: ‘If they’re Keynesians I’m not.’ One of the things Krugman was right about was that JMK has suffered from The Law of Diminishing Disciples.

And that’s all irrelevant today anyhow. The real reason unsustainable deficits pile up is because people want things without paying for them. So politicians have every incentive to give that to them. Countless nations, empires and kingdoms back to ancient times have gone broke or debased their coinage without Keynes ever existing. Trump didn’t push his tax cuts because Keynes said to increase the deficit, same with the Dems’ spending. Politicians just answer to their bosses, the voters, who want ever more somethings while paying nothing. They have to survive elections! That’s it. And that’s how things will stay until something fundamental changes in human political orders.

“Democracy is the theory that the average voters know what they want and deserve to get it, good and hard.”

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 11 2024 at 10:56am

Jim: You may be right about Keynes, but the Buchanan and Wagner’s argument (as I remember it) is different: once the principle of budget equilibrium is broken except in case of war or depression, you can expect the state to find other exceptions. It is not, however, because all voters want this, but because they are rationally ignorant and, as you mention, it is in the interest of politicians to offer free goodies.

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 11 2024 at 11:27am

Dear all: I invite you to consider seriously Jose Pablo’s intriguing argument and try to find what’s wrong with it, if there is something wrong. Just reread his comments. Whether it would be politically feasible or not–in the long run–the basic idea is striking and very much in the line of thought of James Buchanan and the school of constitutional political economy. Consider an individual who, in Jose’s system, has received a tax invoice of $1,000. What I think Jose says is, let each individual decide for himself (or herself, of course) whether $1,000 more of government deficit is beneficial or not for himself. It is beneficial for him if, and only if, his opportunity cost of paying $1,000 in taxes is higher than his opportunity cost of lending $1,000 to the government. The proposal would amount to radical replacement of collective choice about the means of government financing by individual choices. What’s wrong with that?

steve

Sep 11 2024 at 11:54am

Meh. Everyone, or close to it, would decide it’s not worth it. The issue as I see it is that our growth rate used to exceed the increase in debt. Then on top of that it became good electoral politics to divorce tax revenues from spending entirely. Everyone loves tax cuts but they really love them if they dont have to give up any services or Medicare, etc while still having lower taxes. So we are just playing a game of chicken with the debt. Whoever blinks first and cuts spending on Medicare or SS faces losing several elections.

Steve

Jose Pablo

Sep 11 2024 at 12:35pm

Everyone, or close to it, would decide it’s not worth it.

I very much doubt it. Remember that 70% of taxes come from 30% of taxpayers. And that these taxpayers have a pretty high opportunity cost (that’s the reason why they pay a lot of taxes in the first place).

They will be more than happy to get a loan on the government debt terms (not collateralized and with very low interest rates).

I will personally get (almost) any amount of debt under these conditions. I am grateful that the government does that for me (kind of) to a certain extent.

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 11 2024 at 5:21pm

Jose: My summary of your argument was indeed muddled. It should be ignored by going to the real source, that is, you!

Jose Pablo

Sep 11 2024 at 12:23pm

It is beneficial for him if, and only if, his opportunity cost of paying $1,000 in taxes is higher than his opportunity cost of lending $1,000 to the government.

It is even better than that

It is beneficial for him if, and only if, his opportunity cost of paying $1,000 in taxes is higher than the opportunity cost of the marginal debt holder.

The opportunity cost of the marginal debt holder is the government interest rate, and public debt holders are known for having the lowest opportunity cost out there (poor conservative souls). Sure lower than the average American taxpayer opportunity cost. In which case the deficit is a blessing for the “higher opportunity cost average American taxpayer“

Warren Platts

Sep 11 2024 at 4:59pm

If I recall correctly, Jose was saying the other day that he believes the trade deficit is basically free goods & services that foreigners are willing to send to us in exchange for specially printed pieces of paper. And of course the trade deficit is simply the sum of a hundreds of millions of individuals making individual buying and selling choices.

Therefore, the optimal deficit should be just whatever the current account deficit is. That way Americans themselves are not financing the deficit, and if foreigners are willing to finance our fiscal deficit, shouldn’t we let them? As they say on Wall Street, “When ducks quack, feed them!”

Jose Pablo

Sep 12 2024 at 11:52am

the optimal deficit should be just whatever the current account deficit is.

Yes, Warren, precisely so.

My point is that, maybe, we have the current account deficits that we have because people with the wrong incentives are making the decisions about, for instance, the right level of deficit.

With my proposal, the right people with the right incentives and skin in the way will make that decision. Their “revealed preference” will be the right answer to the “right amount of deficit” question. Much better than the one we get now in the polls that elections are (to which, economists, should put little weight, according to Scott’s new post)

Jim Glass

Sep 11 2024 at 10:55pm

You can do a lot of this right now. Don’t pay a tax bill you owe. You’ll incur a debt to the IRS, and owe interest on it as you would any other debt. For the typical individual taxpayer, in practice this can run on for years. These unpaid taxes today total substantial billions of dollars and the Treasury borrows in the market to make up for this tax revenue not received. So far, I don’t see a big deal. It’s pretty much status quo.

Now if you want to regularize this so it occurs on a much larger scale, there will be issues. To provide large amounts of debt, every creditor requires security. Planning to owe the IRS deca-thousands? Then you are going to have to give the IRS a lien on your home or other property. (Of course, today as well, if you decide to owe a large enough amount the IRS will arrange this for itself.)

Sure, with the interest rate necessarily varying for each individual by personal credit risk. And let’s face it, even today, people who don’t pay their taxes aren’t the best credit risks! 🙂

Today’s average rate on unsecured borrowing is 24% (credit cards) Google tells us. Today’s IRS interest rate is 8%, given IRS enforcement powers. Convert the tax bill to just unsecured debt, the average interest rate on it is likely going to have to go over 24% (lots of people get rejected for credit cards) but vary for each individual. Simple!

What is the credit limit for each individual going to be? The IRS is going to have to figure that. How is the interest going to be currently remitted to the IRS? Is it going to be currently remitted? What will the deadline be for paying the principal to the IRS? What’s the enforcement mechanism for defaulters?

The whole original concept seems to be that if people have better uses for their money than paying it to the IRS, they all can just run up a tab with it … forever? What will THAT do for the national debt?? (I have better uses for my money than making payments on my house, car and credit cards. “Hey guys, keep a tab for me, I’ll pay you never!”) OTOH, if interest and principal payments are going to be due and enforced on debt limits all calculated on an individual basis, then — “by Leviathan’s growing limbs!” — we’re just adding commercial banking operations to the IRS.

OR, as Professor Sumner said, people can just pay their taxes and borrow the same amount from a bank. Or borrow even more, if they have enough opportunities!

Jose Pablo

Sep 12 2024 at 12:16pm

I don’t see a big deal. It’s pretty much status quo.

No, nothing to do. This practice will be legal. A legal activity and an illegal one, even if both achieve the same goal, are by no means, the same.

I don’t usually engage in illegal activities even if they make sense to me.

To provide large amounts of debt, every creditor requires security

No, government debtholders don’t require any security (no collateral at all). My proposal is all about passing this prerogative to taxpayers when they have to face their yearly tax liabilities.

Then you are going to have to give the IRS a lien on your home or other property

The IRS already has that. Try not to pay your taxes. You can very easily end up propertyless and in jail. No change.

What is the credit limit for each individual going to be?

The amount of your “true tax liability” (the amount on your tax returns * 1.33 in my example) for the current year.

How is the interest going to be currently remitted to the IRS?

The same way that you pay taxes now to the IRS. Your year interest will be included in your next year tax return.

What will the deadline be for paying the principal to the IRS?

The term that the taxpayer chooses (1,2,3,4 .. 10 … years ). The Treasury will match the aggregate terms that individual taxpayers have picked with that of the government debt issued in the debt markets. Pretty much as the treasury does now, the only difference is that now the ones deciding the term of the national debt will be the individual taxpayers (in aggregate) not the Treasury.

These bullet payments wouldn’t be difficult to face. Remember that the maximum amount of the principal just equals your yearly tax obligation. So will result in the same payments that most people regularly face now every year.

What’s the enforcement mechanism for defaulters?

The same ones that the government has now for the people not paying their taxes. Pretty harsh. Taxpayers will honor their debt.

OR, as Professor Sumner said, people can just pay their taxes and borrow the same amount from a bank. Or borrow even more, if they have enough opportunities!

Yes, but the opportunity is there for taxpayers to borrow at the incredibly good conditions of the Treasury. Why retort to private debt with much worse conditions?! …

It is like saying: “Oh, no, no … these debt conditions are too good, We must (?) have less of this wonderful debt because, you know, we already have much worse private debt available to us” (?? …)

Jim Glass

Sep 13 2024 at 12:30am

Until, like, never?

Nope. One year’s unpaid tax is NOT included in the next year’s tax return. It is a separate liability, collected independently of those for all other years.

Moreover, while one can obtain an installment agreement with the IRS spreading payment of one year’s tax bill over multiple years, it requires periodic payments of interest to be currently remitted just like a car loan or bank loan does through the entire term. So if your taxpayer chooses to have a tax debt for “2,3,4 .. 10 … years ” (15? 20? 25?) is cash money interest going to be currently remitted to the IRS during those years? Or is the taxpayer just running up a never-any-cash-cost exponentially compounding tab?

No, it’s NOT AT ALL the same — and as for “taxpayers will honor” their debts, let’s see…

1) I’m one of millions of American middle-class wage slaves, getting by on my salary, living more or less check-to-check in a rental apartment, not building any great wealth. Then I learn, “Hey, I can not pay my income tax wage withholding by instead owing the IRS the money at a really low rate! For 1, 2, … 10+ years!” And SURELY my utility will be maximized if I use the “opportunity” to instead take that money to Atlantic City every weekend and split it on alcohol, gambling and hook^^ whatever else is down there. So after several years of doing this, with interest, my “tab” with the IRS is, say, $200,000+. And I have NO ASSETS. How will I honor that tax bill? How will the IRS enforce it?

There is a term, “judgement proof” describing debtors who have no ability to pay. Lenders really don’t like to hear that term. That’s why banks require house mortgage-size loans to be secured by house-value-level assets — instead of just handing them out to anybody secured by *nothing* … And why when your tax debt gets big enough the IRS will put liens on whatever assets you have, while you still have them … And why unsecured debt carries a 24% interest rate — to pay for all the defaulters.

2) I’m Tim Cook, CEO of Apple (or boss of any other business). Surely I have many ambitious dream projects I just can’t pursue because of credit risk. No bank will give me the money, and the market borrowing rate is far too high, as lenders require it to cover the high risk. But, hey, if I can borrow big from the IRS at the low, low, risk-free rate for 2,3,4 …10+ years … Why wouldn’t I do that? What could go wrong???

Please correct me if I’m missing something, but … It sure looks like you are proposing to give 165 million individuals and every business in the land the incentive to stop paying taxes for 1,2,3,4 … 10+ years … potentially wiping out up to 100% of the income tax revenue of the Treasury … through “borrowing” from it at the risk-free rate … all borrowing unsecured … with zero way of guaranteeing any repayment. What could go wrong?

Gee, why doesn’t the Treasury pass on its ability to “borrow at incredibly good conditions” to the public NOW, by offering this risk-free rate “wonderful debt” to the public NOW, though direct lending? Why all the needless rigmarole of doing it through unpaid taxes? Put all the commercial banks out of business! If the Treasury issued credit cards charging the risk free-rate instead of 24% to everybody, with no individual credit checks ever required, just think of all the great new opportunities for credit card users everywhere!!!

What could go wrong??

BS

Sep 14 2024 at 12:49pm

People become insolvent. What happens to them?

Lots of people become insolvent. What happens to the tax base?

Warren Platts

Sep 11 2024 at 5:09pm

Pierre, in your spreadsheet above, I see you broke out a special, combined line time, “Mandatory programs plus defense and interest” at $2,443 billion. I’m pretty sure that figure should be $6237 billion. But I’m curious why you think those three numbers together are significant. Because defense spending is going nowhere but up for the foreseeable future because we now have to deter what Nixon called the “Frankenstein monster” that he admitted to creating — viz. China. That is, thanks to all this free trade made possible by Nixon’s “opening” of China, we’re now in a major arms race. And no matter how expensive that is, that’s going to be a helluva lot cheaper than a potential World War III would be, so we gotta do it…

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 11 2024 at 5:50pm

Warren: Two points.

First, you are totally right that my subtotal for “Mandatory programs plus defense plus interest” is indeed the number you calculated. That was my (stupid) mistake. Fortunately, I used the correct 6,237 (your number) to calculate the percentages. Thanks for catching that. I will replace the Table by a corrected one in a few minutes.

Second, I added defense because I think it is perceived as a non-compressible expenditure–and I think this belief is largely correct. But for reasons that have nothing to do with trade of Americans with Chinese consumers or producers. On the contrary, if the US government had let American citizens and residents free to continue trading with voluntary partners from China, the risk of WWIII would now be much lower. This is because the opportunity cost of a war for the Chinese tyrant would have been much higher, that is, Chinese consumers and exporters will now lose much less in case of war and thus will be less angry with their ruler if he brings one. (It is worth reading the articles on China in the current issue of The Economist.) Laissez faire, morbleu! Laissez faire!

Warren Platts

Sep 11 2024 at 7:38pm

Hey I used to work as a bookkeeper and accountant’s assistant (the full extent of my professional economics experience…) I know how it is! But touché regarding Chinese opportunity costs. Nonetheless, if we’re going to run geoeconomic experiments on free trade with Communist societies, it would’ve been less risky, and certainly more fun if we had free trade with Cuba instead of the People’s Republic.

As for ideas on how to eliminate the fiscal deficit, as you noted, we actually ran surpluses from 1998 to 2001. (1969 must have been the result of tapering down the NASA Apollo program that at its peak was eating up 6% of the GDP.) Most probably, the modest surpluses then were due to the late 90s boom that was followed by the 2001 “China Shock” bust. That should give us a clue as to what to do: Grow Baby Grow! And maybe taper it down on the free trade with mercantilist countries.

My own BOTE calculations suggest VERY roughly that a 20% ad valorum tariff on all imports (we can make exceptions for stuff like coffee and pineapples), plus tariffs on capital imports (viz. applying the capital gains tax on foreign investors who own 40% of the U.S. stock market) would raise close to a trillion in tax revenue. And eliminating the trade deficit would eliminate a headwind to economic growth because, after all, Y = C + G + I + NX. Granted, if we could magically get to NX=0 tomorrow, we’re not going to get a 3% boost in GDP growth because retaliation will reduce exports. Nonetheless, if we could juice the economy by even 1 pp as a result, that would be huge!

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 12 2024 at 1:01pm

Warren: You seem to have made progress in economics, but not in national accounting (re: your last paragraph). A reduction of imports cannot increase measured GDP because imports are not part of GDP. Repeat: Because imports are not part of GDP by definition of GDP. Everything is explained in my post “Imports as a ‘Drag on the Economy,’” and the links you find therein.

If you want to argue that a reduction of imports causes a substitution of cheaper domestic production, you need an economic argument, not an accounting argument (even if you found a valid accounting argument). Good luck with that demonstration! You will have to show that all consumers who import and all producers who export are making a bad choice, that they would get their goods cheaper by buying national and selling national! And explain why this does not imply that it’s cheaper if you buy local and sell local only, say, on your street.

Warren Platts

Sep 12 2024 at 3:40pm

We’ve been through this before, and yes, of course, you are right: imports, by definition, are not part of GDP. Further, I agree that if there’s an argument for too many imports, that can’t be based on the GDP equation. I stand corrected.

However, I do have an economic argument and it is this:

The problem is we’ve got ourselves into a collective pickle. As you eloquently put it, “The public debt is a time bomb that will have to be defused or will explode at some point.” (I’ll have to remember that one!) However, the key to defusing the time bomb is cutting the trade deficit wire for two reasons:

One: as I alluded to above, increasing the GDP growth rate would be a big help. And while imports, by definition, are not a part of the GDP, it is nonetheless the case that a big, negative NX represents a big exporting of U.S. demand. And economically, demand is the most precious commodity. If we could reshore a bunch of that demand, U.S. production (aka GDP) would have to increase.

Two: the public debt is largely a direct result of the trade deficit because foreign mercantilists, to a large extent, prefer buying American debt rather than buying American exports. Note that I am not invoking the twin deficits hypothesis. We had a balanced budget in the late 90s, yet still ran fairly big trade deficits.

Hence the dilemma. Do you see? Even if the government could somehow balance its budget, that, in itself, would not defuse the debt time bomb: reduced public debt will simply lead to increased private debt. Why? There’s an old Wall Street saying: “When a duck quacks, feed it.” There will always be Americans willing to take on unwise debt and there will always be American financiers and foreign mercantilists willing to feed the ducks.

Thus we’re in “Be careful what you wish for” territory. Because if there’s any exploding to be done, it’s probably for the best if the government does the exploding since the government has more tools to deal with it. Indeed, shifting the public debt to the private sector practically guarantees an explosion likely worse than 2008. And that in turn would require an astronomical government bailout anyways. Then it’s back to square one…

Jim Glass

Sep 13 2024 at 1:48am

OK, following that, here’s a proposal to increase US GDP: Make every state in the Union engage in only balanced trade with all the other states. Eliminating the negative NX of all states that currently have it will necessarily increase each such state’s demand and thus GDP, and thus the GDP of the USA entirely, by simple arithmetic.

I confess my own state is perhaps the chief offender here. In June of 2024 alone New York State had a trade deficit of $4 billion (exports $7.5 billion, imports $11.5 billion). That is an annual “demand deficiency” of $2,400 for every man, woman and child.

But the true villain in all this is New York CITY. In just June of 2024 it had a negative trade balance of $11.2 billion!!! That’s 2.8 times the entire state’s negative balance — the entire rest of the state actually is strongly positive! At an annual rate this indicates “demand deficiency” in NYC of $16,800 (!!) for every man woman and child! Think of the resulting impoverishment.

The evidence of this is everywhere of course. Compare the great poverty of New York City to the wealth of the NX positive rest of the state, such Buffalo, Schenectady, the farm counties …. If only New York City could slash its demand destroying imports, and as a result get Manhattanites back to productively making their own cheese and blue jeans and such, raising their own pigs to supply their own bacon, imagine how much this demand increase would boost the city’s GDP and how much better off its people would be! Buffalo, here we’d come!

Warren Platts

Sep 13 2024 at 1:54pm

Jim, thanks for making my point for me. Since trade deficits are financed ultimately by debt, it’s not surprising that NYC is drowning in debt. In fact, NYC’s fiscal health is the worst in the nation: outstanding municipal debt is around $171 billion (debt burden per taxpayer = $57K).

I see New York State is also running big fiscal deficits. Meantime, Wyoming’s net exports were $1.11 billion last year. Unsurprisingly, their state government’s problem is figuring out what to do with all their extra money.

It doesn’t have to be this way. New York is sitting on the northern sweet spot of the Marcellus formation. If only they would allow fracking, they could probably produce 10 billion cf of natural gas per day instead of their current 10 billion cf per year. (Pennsylvania produces 20 billion cf per day.) New York’s consumption is about a third of that number, leaving over 2 trillion cf per year available for export. If converted to LNG and exported to Europe, New York’s exports would increase by $13 billion, leaving New York with a $9 billion trade surplus. So yes, New Yorkers would be better off economically if they didn’t pay attention to the “Trade deficits don’t matter!” shibboleth.

Jim Glass

Sep 13 2024 at 11:09pm

Warren Platts wrote:

Warren, first, I want to reassure you with good news that should make you feel better about that! Seriously. Not kidding.

Perhaps you remember that after the Civil War the USA ran big trade deficits through near the entire period until World War I — and grew from a backwater agricultural country to the world’s #1 industrial power. Via endless trade deficits! How could that happen? Well …

You’ve never mentioned the *rate of return* on debt/investment. Back then the US borrowed at 6% from London — actually, London brought eager European investors to us — and we invested that at 10+% in railroads and steel plants, etc., across the country. Borrowing big made the US rich and powerful. Or consider it: accepting foreign investments brought to us — it’s the same thing.

Yes, trade imbalances are balanced with a trade deficit/capital surplus. That is trade finance. You *never mention* the capital surplus that is the other side of the coin! Trump himself financed one of his most valuable buildings with a loan from China! That’s the trade surplus in action. Was Trump constructing a building with a cheap loan bad for America?

So is a trade deficit/capital surplus bad or good? Are we putting ourselves in hock? Or are other nations bringing their money to invest here — **forcing a trade deficit in the process**, as the other side of the accounting coin — which is good!? How to tell??? Let’s look at the **returns** from trade finance on US investment abroad and foreign investment in the USA…

Hey, the USA is making a PROFIT on all this debt you are talking about. And we can do something that makes a profit forever! Feel better? And yes, the lion’s share of this profit is going to New York City. “The finance capital of the world”. Trade’s not leaving it broke now, eh? Huge GDP, $1.2 trillion, $2.2 trillion including the metropolitan area. Now….

Not Even Close. NYC’s S&P Global credit rating is AA-. Chicago is BBB+ (I don’t know who “Truth in Accounting” may be with its trademarked rating system, but I prefer the international financial market.) Also, the US state with the largest trade surplus per capita is Louisiana. It’s credit rating is AA-. New York State’s credit rating, with its big trade deficit, is AA+, two notches higher. Wyoming’s is AA, also lower than New York’s. (And Wyoming’s entire state GDP is $39 billion compared to Manhattan’s $900 billion — you really compare them?)

Back to the former subject of GDP. You were correct, it is the most important consideration. The “P” in it is production, which = “income”, and increasing productivity to create “more from less” is *the thing* that makes societies rich. That’s why you don’t want to force equalized trade between US states to “save” NYC from its trade deficit. If NYCers have to start making their own cheese and clothes and raising pigs for their own bacon, their GDP will plunge and they will become poor. Wisconsin will be poorer too as it will no longer be able to sell cheese to New York to get funds it needs to to buy cars from Michigan, etc…. Each state’s trade deficit eliminated, GDP plunges, country impoverished. (See: Smoot-Hawley Tariffs, Great Depression)

Trade is about increasing productivity, and productivity is the root of everything. There’s no need to kneecap it for fear of making a $200 billion annual profit from international trade finance.

(BTW, if you want to say NYC has pretty poor management, as a NYCer I’ll surely agree. But that has *nothing* to do with trade, and plenty of cities have a lot worse: Chicago, Newark, Oakland…)

Warren Platts

Sep 14 2024 at 9:44am

Jim, I mentioned capital surplus at least three times in the posts above you are responding to.

Anyways, your analysis is completely off base for the following reasons. First, I never said trade deficits are inherently bad. Sorry if I gave that impression. As you rightly point out, the USA ran trade deficits practically through the entire 19th century. But the USA was a developing country back then. Thus there were vast, productive investment opportunities that exceeded the USA’s ability to fund them. Foreign debt in that case was easily repaid since debt servicing capacity increased faster than the debt.

But if the trade deficit in the 19th century was a good thing, does it follow that the 21st century trade deficit is also a good thing? Of course not! The USA is now a fully developed country. Sure, there are desired, productive investments like the vast natural gas reserve underlying New York that extends all the way up into Vermont that are going unfunded. But that’s because of political gridlock — not because the USA is suffering from a shortage of capital.

In fact, foreign funded greenfield factories and casinos constitute maybe 1% of total foreign capital inflows. So if the vast majority of foreign inflows are not going into productive investments, then where are they going? There’s only one place they can go: unproducitive investments. And even this wouldn’t be a problem if the debt didn’t grow faster than the GDP growth. But in recent years, debt growth has vastly exceeded GDP growth to the poing where even an ardent Libertarian like Pierre Lemieux is getting worried about it!

The CATO article you cite says, “America’s net international investment position is easily sustainable.” If that’s not just plain crazy, then they are using a very non-standard meaning of ‘easily sustainable’. In 2006, NIIP was -13% of US GDP. As of 2023, it stands at -71% of GDP with no sign the downward trend will reverse itself. Historically, when a country’s NIIP gets below -60% of GDP, bad things start to happen. Shall we see how far we can push our luck?

As for NYC’s vaunted productivity, I don’t buy it because by that measure Washington DC is the most productive place in the nation by far with a GDP/capita about 2.5X that of New York that’s in 2nd place. I guess we can call that productive, but that’s not the kind of productivity we should desire. Moreover, if New York is running a trade deficit, that’s not because of the workings of the free market or other powers of efficiency. As I’ve already proven, that’s because of ill-advised managers emplaced by irrational voters..

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 14 2024 at 9:52pm

Warren: My apologies in advance, but when you let your nationalist/collectivist heart get excited, it’s like if you wanted to make me regret to have said that you made progress in economics! Keep it cool and methodological-individualist. Let me illustrate with just one of your paragraphs:

First sentence: Don’t confuse the productivity of private producers (including financiers, of course) with the productivity of government employees (whose productivity is defined as their gross income). Second sentence: Who’s “we” who decides what “productivity” “we” want? Analyzing the economy is studying the social consequences of individual choices, not imagining big collectivist organisms dealing with each other. In a free society, each individual decides for himself. Your third and fourth sentences: I don’t know exactly what you mean by “ill-advised managers emplaced by irrational voters.” Certainly rationally-ignorant voters, politicians, and government bureaucrats are not competent to decide what “we” want and how “we” should get it. It’s not Russia or China here, or at least it should not be. Laissez faire, morbleu! Laissez faire! (Sorry if my own little individualist heart got excited.)

Jim Glass

Sep 15 2024 at 2:16am

Warren Platts wrote…

Okay.

It’s odd to read a claim that today’s #1 world economy offers fewer investment opportunities than a $19th century 2nd-tier agricultural country. But as I said before, it’s an empirical question, which is why I referred to the USA’s *return* on its net trade financial position: +$200 billion annually. Looks good to me!

Sort those countries by *profitable* and unprofitable investment positions. I suspect we’ll fund it’s not the size of the investment positions, but the size of the profit or loss on them that matters. Just a guess. But do show me some countries with steadily profitable NIIPs that suffered bad things as a result. I have a hard time imagining punitive profits.

Earlier you wrote “the public debt is largely a direct result of the trade deficit because foreign mercantilists, to a large extent, prefer buying American debt rather than buying American exports” as if investing in the US instead of buying its products is a *bad* thing. Which is much like saying about Apple, “Look how many people prefer to buy its stock and bonds rather than buy an iPhone or Mac!” The horror! High demand for buying Apple’s stock and bonds — increasing Apple’s liabilities — lowers the cost of its operating capital. Foreigners buying $4 trillion of T-bonds lowers US cost of capital for everyone. Chinese bankers investing directly in the US got Trump an apartment building. Bad things? AND those foreigner don’t buy that $4 Trillion because we’re desperate but because they have high demand for the world’s safest investment. That’s why they collect (and we pay) the *world low risk-free rate*.

First, your are saying that in NYC the nation’s leading financiers, health researchers, entertainment firms, universities and so on don’t contribute to GDP by their market value because Washington is a city of politicians and bureaucrats. Logic?

Second, to give the DC politicians and bureaucrats their due, the do have the task of managing $5 trillion of annual revenue, $5.5 trillion of assets, *and* international relations world-round which if bungled could lead to nuclear war. If you could bid THAT task out at market rates, the people in DC doing it would probably make a heck of a lot more than they do now. (The politicians and bureaucrats would probably a lot higher quality than today’s too — but another subject.)

Of course, national and international finance has nothing to do with free markets and efficiency.

OK, then, tell you what: First better advise Manhattanites to get rid of their trade deficit by rationally becoming self-sustaining in farming, weaving and pig-raising, eliminating their “bogus” non-market $900 billion of GDP in the process … then tell LeBron James, Shohei Ohtani, and Joe Burrow to stop running up their staggering personal trade deficits —

with other cities, states and of course nations — by cutting their time spent playing games to earn the income they spend running up their deficits, to instead spend it on deficit-cutting self-sufficiency tasks in farming and the like…. then look at your own personal trade deficit — I am sure you buy things from all kinds of locations without selling anything there, including from foreign countries — and wag a finger at yourself in the mirror.

All these trade deficits at the state, city, and personal levels must be stopped! Because they all compound to create a national net international investment position that earns $200 billion in profits annually! …. Oh, wait….

Warren Platts

Sep 15 2024 at 4:38pm

Pierre, I mostly agree you are right regarding methodological individualism: the economy is mostly the social consequences of individual choices. But when trying to understand New York’s fatuous environmental policies that prohibit fracking, new pipelines, or LNG export facilities, we leave the realm of economics and enter political science. Then we have to talk about individual policy entrepreneurs, officials, elected and unelected, lobbyists, community activists, and individual voters and so forth. Here the social consequences are still based on what individuals choose to do (just as the choices individuals make are based on what their atoms and molecules “choose” to do — this is another way of saying that individual free will is a psychological illusion, but no need to enter those metaphysical weeds), and hence subject to a methodological individualist analysis, but it’s the furthest thing from a free market!

Warren Platts

Sep 15 2024 at 4:45pm

Jim, you badly misunderstand the significance of trade deficits and what NIIP even is. Regarding the difference between developing versus developed economies, it’s virtually definitional that developing economies cannot themselves fund all the productive investment that’s desired. The reason Europeans invested in USA was precisely because in Europe there was a surfeit of capital combined with a dearth of productive investments. The excess capital found a home in the U.S. as well as various imperial possessions.

Yes, there are still many investment opportunities in the U.S. Some of the needed investment is even going unfunded. But is that because of a shortage of capital and hence why we need more foreign investment? No, for the third time, if needed U.S. investment is unfunded, that’s not because of a shortage of capital. It’s because of politics or some other reason.

Also, there is no such thing as “profitable” or “unprofitable” NIIPs. The very idea does not exist. Just because the U.S. ran an average $200B primary income surplus from 2017 to 2021, does that mean U.S. NIIP is “profitable”? (See table 1 from which that $200B number comes from.) No. The $200B “profit” was not nearly enough to balance the -$900B goods trade deficit, resulting in a $543B average current account deficit over the same period.

But it’s worse than that. In 2017, NIIP was -$7.8 trillion; in 2021, NIIP was -$18.8 trillion, for an average annual increase in the negative balance of -$2.2 trillion. Roughly speaking, the NIIP can be thought of as the sum of all current account deficits and surpluses an economy has had, adjusted for value. So why the -$1.7 trillion annual difference? The preceding 5 years only had a -$100B difference on average.

I don’t know what the whole story is, but no doubt a large part of that is because of currency fluctuations. US liabilities held by foreign investors are denominated in dollars, whereas US owned foreign assets are denominated mainly in foreign currencies. So when the dollar strengthens, the value of U.S. owned foreign holdings goes down. There are other factors too, like relative performance of equity markets etc. But the bottom line is that NIIP = -75% of GDP and it looks like it’s going to get worse.

And yes, it would be better if foreign economies bought U.S. goods and services instead of Apple stock. Apple doesn’t need more investors: in fact I just calculated that over the last 10 years, APPL stock buybacks totaled $653 billion! In other words, they have more cash than they know what to do with. They don’t need foreign investors.

As for foreigners buying trillions of T-bonds “lowering the cost of capital for everyone,” if you were right, then the cost of capital would be more expensive in the chronic surplus countries compared to the mother of all deficit countries. And yet the empirical pattern is just the opposite: mortgage rates in the U.S. are around 7%. Compare Japan (1.5% to 2.5%) and Germany (3% to 4%).

As for New York investing in “becoming self-sustaining in farming, weaving and pig-raising,” that’s a typically Boudreauxvian straw man based on a conflation of balanced trade and autarchy. Countries and states should export what they have a comparative advantage in. New York has a huge comparative advantage in natural gas. If only they would let the free market be free, New York would be running an internation trade surplus. No need to expand pig-raising.

As for me “buying things from all kinds of locations without selling anything there,” that’s another straw man based on a conflation: this time between bilateral trade deficits and overall trade deficits. For an individual to follow the example of the USA and consume more than they produce while financing the difference with debt over the course of 50 years, that’s a good recipe for going broke…

Russ M

Sep 11 2024 at 7:40pm

A case study on how things went/are going in Portugal might be useful as a reference.

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 12 2024 at 3:55pm

Russ: What do you mean?

Warren Platts

Sep 12 2024 at 4:07pm

I think he means the Euro “PIGS” (Portugal, Italy, Greece, Spain), who all had big debt time bombs combined with big trade deficits. Then the bombs exploded with the Euro crisis, causing wages to be slashed, skyrocketing unemployment, and trade surpluses — except, so far, for Greece. Problem is the root cause wasn’t addressed: German mercantilism. Hence larger U.S. trade deficits will be incoming…

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 14 2024 at 9:56pm

Warren: The problem was state dirigisme and interventionism. Remember that Soviet Russia did not collapse because of its trade deficit and import of foreign capital. Laissez faire, morbleu! Laissez faire!

Warren Platts

Sep 15 2024 at 6:20pm

Yep. But try to tell that to the Germans!

Jose Pablo

Sep 13 2024 at 3:02am

Nope. One year’s unpaid tax is NOT included in the next year’s tax return. It is a separate liability, collected independently of those for all other years.

Under the new system, interest and principal payments on your “not-yet-paid-taxes-from-previous-years” (aka “my individual contribution to the national debt”) will be included in your next year’s tax returns. I invented the system so I should know.

instead take that money to Atlantic City every weekend and split it on alcohol, gambling and hook^^

If your point here is that if American taxpayers realize that paying back the national debt or having less deficit basically means expending less and not going to Atlantic City and not having that new car and going less on vacation they won’t want to reduce the national debt, I can agree more with you.

But if your point is, as it seems, that what the American taxpayers “truly” want is having deficits and going more to Atlantic City, then the government should give them what they truly want.

Your argument that they are but small kids unaware of the perils of the debt and that should listen to you and behave according to your concerns sounds a little paternalistic to me

Jose Pablo

Sep 13 2024 at 5:46am

instead take that money to Atlantic City every weekend and split it on alcohol, gambling and hook^^

Tim Cook, CEO of Apple (or boss of any other business). Surely I have many ambitious dream projects I just can’t pursue because of credit risk

If your point here is that my thought experiment could reveal the preference of American taxpayers for more unsecured debt of the “Treasury type” (debt that they are, very likely, never going to have to pay back before they die and that their debtholders have no mean to force them to pay), I agree with you. It may be the result of this exercise. Makes sense. I don’t think it is the only possible outcome but certainly, it is one of them.

What I do think is that for rational well-behaved, god-fearing taxpayers with high opportunity costs or with outstanding private debt, the rational thing to do is to engage in more government debt (which has very favorable conditions). For them makes more sense to invest their tax money in high-return endeavors or in paying back their private debts than in paying taxes.

Jim Glass

Sep 13 2024 at 8:05pm

I’m glad we agree. I’m sure we’ll also agree that upon the adoption of such a program — the result of which “may be” to bankrupt the Treasury by eviscerating its ability to collect any tax revenue at all — the Treasury sure won’t be borrowing at the “risk free” rate any more!

:

“Treasury type debt” will be extinct. No favorable conditions to share with anyone then.

Government without any taxes. Who could object? If you want to take a shot at it, try the MMT way. Just stop all taxes and fund the government entirely with ever more debt. Done. Some MMTers say it will work. Maybe they are right. Who knows? Let’s try and see. What could go wrong?

Jose Pablo

Sep 14 2024 at 6:30am

the Treasury sure won’t be borrowing at the “risk free” rate any more!

Yes, we indeed agree!

The government interest rates are the right signal to know when we have too much deficit.

Assuming (granted, probably not a good assumption, but can be relaxed later) that private market interest rates are independent of government interest rates, we should “deficit ourselves”, at least, to the point at which private and government rates converge.

Actually, I think that increasing the deficit is the last Pareto efficient policy left out there:

For taxpayers with high-return investment opportunities paying less taxes (so increasing deficit) and investing their tax money makes sense

For taxpayers with outstanding private debt, paying less taxes (so increasing deficit) and using their tax money to pay back part of his/her private debt makes sense

For other taxpayers, paying fewer taxes (so increasing deficit) and investing their tax money in buying government debt should leave them (assuming no transaction cost) indifferent.

Of course, you are right, in this process of increasing the deficit government interest rates are the key indicator to understand when we have enough of a good thing. But, I hope we also agree, that, very likely, a good thing it is.

Jose Pablo

Sep 14 2024 at 9:02am

Just for clarity. What I am saying has nothing to do with the MMT way. That’s a straw man fallacy improper of you Jim. You sure see the difference.

Thomas L Hutcheson

Sep 13 2024 at 11:42pm

We need to make deficits < Σ(expenditures with NPV>0). Personally I think the main way to do with should be with a combination of progressive consumption taxes and a VAT. About the only expenditures I can think about needing to be eliminated is ag and ethanol subsidies and hazard insurance.

Jose Pablo

Sep 14 2024 at 9:15am

That’s a very interesting perspective, Thomas.

But, why not include the “=” sign in your equation:

Deficits ≤ ∑ (expenditures with NPV>0).

But, from your utilitarian perspective, the Government should only pursue expenditures with NPV>0, in this case:

∑ (expenditures with NPV > 0) = Total expenditures

This would leave us with:

Deficits ≤ Total expenditures

I will go for the “=” , why not?

Just be aware of the, very valid, Jim point: the bigger the deficit (the sovereign debt) the smaller the number of expenditures with NPV > 0, since the cost of financing the expenditures will increase.

Warren Platts

Sep 14 2024 at 9:54am

Good point. And the trade deficit only adds to that debt and thus cannot lower interest rates. If trade deficits lowered interest rates, then surplus countries would have higher interest rates. Yet surplus economies like the EU and Japan have lower interest rates.

Jose Pablo

Sep 14 2024 at 12:30pm

In fact, this is another benefit of national debt I hadn’t thought of. The level of interest rates (and interest payments in absolute terms) should limit the expenditures of a utilitarian government.

Not a minor advantage since government officials (as many American taxpayers, by the way) are too easily fooled into believing that collected taxes are “free” (have no cost).

Imagine private company A wants to pursue a new project. Company A’s CEO would be immediately fired if he/she says to the Board something like:

“We should finance this new project with shareholders’ funds since banks charge interest on their loans and shareholders’ funds are free”

Shareholders equity is not free. Even though there is no “shareholder’s equity opportunity cost” entry in the P&L

Thomas L Hutcheson

Sep 14 2024 at 4:56pm

Yes maybe it should be =.

BTW _this_ criterion does not imply that expenditures with NPV<0 should not occur, just that one kind of consumption should be financed by taxes on another kind of consumption. If some taxes are on income and not consumption, the criterions needs further modification.

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 15 2024 at 9:14pm

Thomas: I am curious about how you argue for expenditures with NPV<0.

AMW

Sep 15 2024 at 11:01am

The real question is this: If the US is drowning in debt, why is the guy in the banner image drowning in cash?

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 15 2024 at 2:02pm

AMW: Good question. Because he already has $5.5 trillion in annual income. (And because one has to keep it simple with DALL-E!)

Grand Rapids Mike

Sep 15 2024 at 3:31pm

It is puzzling that the debt so far has not spiked long term interest rates. The 10 yr bond has recently declined to under 4%. In Japan their debt is approaching 250 % or more of their GDP, where I understand the Bank of Japan owns a huge portion of the debt. So at what debt level as a percent of GDP will cause interest rates to spike.

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 16 2024 at 2:07pm

Mike: That’s an interesting question. A big part of the answer is given by the Government Accountability Office on Pages 21 and 54 of its Financial Report of the United States Government:

In clear, the “sovereign power to tax” of a sovereign government (including those not as open about it as the US government) allows it to loot the country. Especially in a rich country with a “wide economic base” and a powerful tax agency, the government has a wide potential income against which it can borrow.

Warren Platts

Sep 16 2024 at 3:33pm

Exactly why I was saying that if there’s a debt time bomb in need of exploding, it’s probably for the best if it’s the government that manages the explosion, as opposed to the private sector. Cf. Lehman Bros.

Comments are closed.