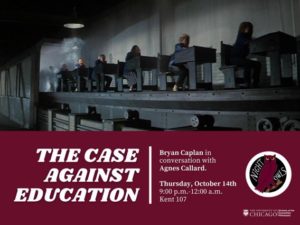

I promised last week to post some further highlights and thoughts on co-blogger Bryan Caplan’s recent 2.5 hour session with Agnes Callard at the University of Chicago.

Here they are:

About 42:00 to 46:00: Bryan wisely suggests that students who have interests talk to the most interesting faculty at the college they attend and makes the point that even at low-level schools there are interesting faculty just dying to share what they know. He tells a great story about Soviet historian Richard Pipes. I’ve already told mine about an early interaction with the great economist Arnold Harberger.

Around 47:30: Bryan asks the students how many of them had a teacher before college who motivated them. We don’t see their hands but Bryan’s reaction suggests that many did. I couldn’t think of a single teacher, from Grade 1 to Grade 12, who motivated me about the material taught. The closest I came was Mr. Brian Parker, who noticed that it was April 1967 and I hadn’t even applied to college even though I was planning to attend in the fall. He hauled me into his office and we sat down and together we filled out the application forms to the University of Winnipeg and the University of Manitoba. I was accepted, with some of the remaining scholarship money, to both.

Somewhere later, I can’t remember where, when Bryan was talking about the strong pressure to get a degree even when one isn’t needed for a person to do the work well, I thought of a true story and I wonder how it fits his signaling model. The daughter of a friend of mine finished high school but didn’t go to college. Instead she joined the Navy for 4 years and came out of it as a pretty self-confident woman. She worked her way up in a firm and they said a number of times that her work was very good. But she hit a glass ceiling. No, not the female one, but the “absence of a degree” one. They told her that if she wanted to be promoted further, she would have to get a bachelor’s degree and that they would give her time off so that she could attend college part-time.

How does that fit Bryan’s signaling model? She sent a strong signal by lasting 4 years in the U.S. Navy. Once the firm had that signal and even admitted that she could do the next higher job, why put her and them at great cost so that she could get the job instead of simply promoting her? Were they simply on automatic pilot? Maybe, but I wonder.

1:09:00: No caste system and no underclass in Germany or Switzerland. And not a big prison population of young males. And the reasons why. I found this one of the most exciting and informative parts of the whole Interview.

1:22:00 to 1:24:00: Agnes Callard mistakenly says that people are “deprived” of the best things and Bryan corrects her: they aren’t deprived; they just don’t choose those things. Notice how Agnes still returns to the “deprived” language.

1:25:00: The impressive things people did in their teens 50 years ago. Why? They had time. They weren’t all going off to college.

I remember thinking something similar when I used to read the local newspaper regularly 15 to 20 years ago. I noticed the amazing story about a 12-year-old girl flying an airplane from coast to coast, and similar stories. One day when I was reading such a story, the reason hit me like a ton of bricks. All these stories happened over the summer, when the kids were free to, pun intended, spread their wings.

1:50:00: Back to Bryan’s point just above. Read bios of people from 50 years ago and see the amazing things they did while young. When I was 16 and about to start college, I read Sammy Davis, Jr.’s autobiography, Yes I Can. I found it very inspiring. Also, he started working at age 2.5. I’m not recommending that, but it did have huge upsides: he learned the world of work and built some serious dancing skills at an early age. In my education chapter in The Joy of Freedom: An Economist’s Odyssey, I talked about a question on Sammy Davis’s child labor that I asked a bunch of education scholars at a Hoover Institution conference in the mid-1990s.

Here’s the question I posed:

One of my heroes when I was a teenager was Sammy Davis, Jr. In his autobiography, Yes I Can, he tells of going on the road with his father and uncle as a performer starting at age two-and-a-half. Sammy Davis, Jr. never went to school. But in every state today, governments require attendance at school. They enforce that requirement by threatening noncomplying parents with prison sentences. My question for each of you is, if you were in charge back then, would you have been willing to send Mr. and Mrs. Davis to prison?

Three of them–Paul Petersen, Herb Wahlberg, and Williamson Evers–said they would not have been willing to send Sammy Davis, Jr.’s parents to prison. The other eight–John Chubb, Chester Finn, Jr., Eric Hanushek, E.D. Hirsch, Paul Hill, Caroline Hoxby, Terry Moe, and Dianne Ravitch–said that they would have sent his parents to prison. One of the eight, Dianne Ravitch, said, “For every Sammy Davis, Jr., there would be one thousand kids whose parents didn’t care.” The purpose of compulsory attendance, she implied, was to keep the parents in line.

1:51:00: Bryan’s tips sound like my tips to undergrads that I often give at the end of talks to undergrads: don’t automatically go to graduate school, law school, or an MBA. Many of your professors will try to lead you there, especially graduate school, but part of the reason is their own love for scholarship and the other part is that most of them don’t know much else about the world of work.

1:52:00: Low-skill jobs are NOT disappearing.

2:05:50: Bryan actually considered working at Target during lockdown. I get that.

2:10:00: When you’re reading a book or article, highlighting doesn’t work. I remember seeing a student from my class when I was over in the library just before class started. I went over to talk to him and saw that he was doing the reading for the class. I saw that he was highlighting. I had already graded enough of his work to see that he was not a strong student. So I thought I would try to build his morale by asking him a question in class, just 15 minutes later, the answer to which I had just seen him highlight. He had no clue. That was my ah-hah moment.

READER COMMENTS

Alan Goldhammer

Feb 3 2022 at 5:54pm

This is unfortunate for you. Do you know why this happened? Was it poor quality of teaching or something else. I had a number of teachers who were excellent and provided me with a lot of intellectual stimulation in a number of areas. It was my high school chemistry teacher who prompted me to major in that field and subsequently I also got a PhD. I also had outstanding English and History teachers.

Philo

Feb 3 2022 at 11:10pm

My experience matches David Henderson’s; maybe my personality makes me resistant to inspiration. I liked some of my teachers, and I thought some of them were reasonable effective at teaching. But insofar as I was inspired—usually to a rather modest degree—it was because I found the material we were studying intrinsically interesting. And most of what we studied was at least fairly interesting: I always felt a drive to learn as much as I could about the world in all its aspects.

BC

Feb 4 2022 at 3:19am

Did your other high school chemistry classmates also go on to major and get PhDs in chemistry? I am always surprised at how teachers can have such a major impact on individual students without having similar impact on other students that sit in the same classroom, exposed to the exact same lessons and teaching style.

Alan Goldhammer

Feb 4 2022 at 8:00am

Two others did and I know of a couple more that got MDs and went into clinical research. This was out of a class of 30 IIRC.

I have to say that I am saddened that so many were not inspired by their teachers. Perhaps San Diego was an anomaly when I was growing up but as noted, many of the teachers I had were outstanding with only one or two truly bad.

BC

Feb 6 2022 at 3:18am

What about chemistry classes taught by other teachers in your school (if applicable)? If much different, then I guess that would be a pretty strong argument for merit-based pay. Many teachers unions seem quite skeptical of merit pay though.

“many of the teachers I had were outstanding with only one or two truly bad”

I would guess that about 50% of my teachers were above average and 50% were below average, at least compared to an appropriately defined peer group. I do think, though, that about 10% of them were in the top decile.

Mark Brophy

Feb 4 2022 at 6:44pm

If a history teacher doesn’t inspire you, it’s likely because your personality makes you resistant to inspiration. History teachers tell stories about people for a living, a very interesting subject that will fail to increase your worth in the job market. Math and chemistry teachers should also tell stories but they usually follow a curriculum that’s boring.

Litigators tell stories for a living, too. If a lawyer has the law and the facts on his side but fails to persuade a jury, he has failed to tell his story well. Good litigators take acting classes to tell better stories and make themselves more persuasive.

Mark Z

Feb 3 2022 at 6:53pm

I had a few teachers who were great teachers and taught me interesting things, none of which I ever made use of. Basically they just helped me cultivate intellectual hobbies irrelevant to career or anything practical. I’m not sure if that counts as motivation.

The teacher I had who motivated me in the most important way for my career was a humanities professor I had who was a great teacher, but more importantly: he convinced me not to pursue a graduate degree in his field because the job market for it was terrible, so I chose a more practical field.

Dylan

Feb 4 2022 at 10:12am

I find this interpretation of motivation a little odd. I don’t think any of my high school or earlier teachers particularly motivated me in a specific career direction, which is a good thing, since my current career didn’t exist when I was in school, in fact it didn’t really exist until 15-20 years after I graduated. I did have teachers who told me advice that I took to heart, which is that college is mostly about getting through, not what you learn when you’re there. And, you should focus your attention on two things academically when you’re in school 1) pick subjects that you’re generally interested in, not the ones that you think will lead to the best career and 2) you need to make sure you learn how to learn, because many of the careers you train for now won’t exist in 5 or 10 years, and you need to make sure you know how to be ready for whatever is next.

But, if we read motivating as inspiring, which David seems to, I think my most inspiring teachers were those that inspired me to examine life and try to figure out what it means to be a good person. Of those, I’ve been lucky to have several over the years, although 2 in high school particularly stick out, both English teachers.

KevinDC

Feb 3 2022 at 8:53pm

Nor can I. The teachers in my public school seemed like their goal was to embody every negative stereotype that exists about public school teachers – they just sort of disinterestedly droned out of the teacher’s version of all the textbooks, and that was it. My school experience was the cliched version of the DMV from comedy shows – everyone who worked there ranged from openly disinterested to actively resentful about doing their job.

One possible signaling explanation for these things is that the firm isn’t just interested in the signal the employee sends them. They also worry about the signal their employee sends to the world in general. Even if they know this worker was up to par without a degree, the rest of the world still expects people in the upper levels of a firm to be college educated. If they start to allow people without a degree into the upper levels of an organization, that might make them look bad were it to become known, particularly the more common it becomes. For it to be known “half of the leadership at Company X only has a high school diploma” can itself be a bad signal to people outside the firm, so firms might just make it a hard and fast rule to keep that from happening.

David Henderson

Feb 4 2022 at 7:10am

Good point about signaling.

David Henderson

Feb 4 2022 at 7:13am

I want to make clear that I had a number of good teachers, a few bad ones, and a number of information-between. Without thinking too hard about it and working my way through the 11 years I was there (my parents encouraged me to skip Grade 4, which I did), I would say that 40% were good, 15 to 20% were bad, and 35 to 40% were in between.

Not one inspired me.

jjap

Feb 4 2022 at 10:33pm

About my K-12 teachers, I have more negative things to say than positive.

When I talk to people about how schooling doesn’t work, I usually only have to say “but you went to these schools. You have first hand knowledge about how it didn’t work or care about you.” But as Bryan mentioned, most people easy accept this… then immediately doublethink into subjecting their kids into the same system.

I greatly admire Bryan’s ability to absorb rants that involve fantastical assertions that could only come from a university campus (the oppressed would be more into art if they weren’t starving and only offered their oppressor’s art; everyone wants a life of mind, but in different ways) and respond to them with something productive. On top of that, he doesn’t neglect to undercut those false assumptions with data/studies/reality in a straightward, calm way.

Dylan

Feb 5 2022 at 2:31pm

Different circles I suppose, but I’d wager for the vast majority of people I hang out with, school DID work for them. This goes double for the educators, they liked school so much they decided to never leave.

I’m of course aware there’s a large chunk of people that school doesn’t really work for, where it is just a means to an end. There’s a reason that when my intro Soc professor made Friday classes optional, that only 10 or so people showed up out of a class of 150…but man, were those sessions good. Being in a class with people that really, truly want to be there to learn is an amazing thing.

Daniel B

Feb 6 2022 at 2:01am

Let me tell a personal story that I think illustrates a serious problem of the education system.

When I was taking AP Literature and Composition my senior year of high school. The teacher had us do assigned readings of the books (e.g, read chapter 3) and free-response quizzes on those assigned readings. I remember her telling us that she could tell whether we had used SparkNotes and didn’t do the readings from our quiz answers (the quizzes weren’t open book so we couldn’t just look up the answers). In other words, it supposedly was in our best interest to actually do the readings, because otherwise we’d get penalized on the quizzes.

She was wrong; there was a simple strategy to trick her. I would simply read the SparkNotes page for the chapter of the book we were reading, then I would quickly skim the chapter so I could get enough details for the quiz to make it seem as if I had actually read the chapter and thought about it myself. I wasn’t friends with a lot of people in the class but I suspect that the people near me were using the same strategy (I remember getting confirmation from one of them that yes, he got away with depending on SparkNotes for the quizzes). I soon stopped doing the readings and I think I got an A in the class (and a 4 on the AP test). I never got caught and I also remember nothing from the class 🙂

The lesson I learned from this experience? Teachers easily overestimate their ability to make uninterested students (I was only taking the class because I felt I had to be, thanks to parental pressure) learn from or be interested in what they’re teaching. Sure, the teacher could have been bluffing all along, hoping no one would call her bluff. But what happens when someone does? How would the teacher know the extent to which people called her bluff? Judging by my memory of her warning us not to use SparkNotes, I’m pretty sure she wouldn’t have approved my behavior. Yet despite her intent for me and others to not use this strategy, we did – and got rewarded for it. We got the good grades and more free time!

“Why do students focus on grades rather than learning? Because they follow the money” (The Case against Education, 30). I think that quote is very accurate and very relevant to my story. I was way more focused on grades than on learning anything from my AP Lit class. Even in subjects that I was more interested in – such as history (AP Euro, AP US History) – I was more focused on the grades. I barely remember anything from even my history classes, despite the good teachers I had in them and my interest in history. More generally, I absolutely don’t remember being taught “how to think” or anything like that. I didn’t go to a poorly ranked high school either (quite the opposite; it was pretty highly ranked by Newsweek back in 2013).

‘There has developed a tendency to speak piously about education as if it had an aura around it–something not to be defiled with facts or common sense. But great numbers of recipients of educational “opportunity” are in school not because they want to be, but because they have to be. They are part of a vast army of scholastic draftees, going to school with the attitudes of draftees. Much of the vandalism, falling standards, and even violence that erupts at all levels of school are a natural consequence of keeping millions of people in a place where they fundamentally don’t want to be’ (“Educational Draftees” by Thomas Sowell, Sept. 12, 1979; found on page 98 of this book).

I don’t agree with everything in Caplan’s book but I think it definitely “defiles” education in the sense above. It’s a must-read and I haven’t thought about education the same since. One of these days I have to watch the massive Caplan-Agnes interview.

Comments are closed.