It is well known to economists that a rational decision-maker will not include sunk costs in his decisions. Since sunk costs are unrecoverable by definition, they have nothing to do with decisions made now for the future. Only future costs are recoverable: you simply have to incur them. Some people do not seem to understand that.

In a report on Apple’s imminent and risky launch of “mixed reality” goggles, the Wall Street Journal tells us (“Apple Is Breaking Its Own Rules With a New Headset,” May 12, 2023—my underlines):

Executives and tech analysts say Apple isn’t waiting longer because it would take too much time to make its ideal version, competitors are already in the market and the company has already devoted a lot of capital and resources into developing the headset.

What the company has already spent in development costs should not weigh into whether it launches the product now or later or never. Previous development money is sunk and not recoverable whatever decision is made now. Given the direction of the arrow of time, one makes decisions to change the future, not to change the past (except if you work for the Ministry of Truth, but even then you can change the past only as perceived and starting from today).

Suppose that you have invested $500 in some project that is not producing and unlikely to produce any return, but that investing a supplementary $10 in the project will very likely bring a net profit of $5. The $10 would thus bring a return of 50%, notwithstanding that the accounting return on the total investment will be less than 1% ($5 / $510). Of course, you should invest the $10, except if you are an extreme risk-averter or you know another investment that will bring a return of more than 50% with near certainty. When you make the decision now, only the 50% return on $10 will guide your decision, not the return of less than 1%. Indeed, if the return on the $10 were forecasted to be 2% (20¢), a rational decision-maker would probably decline to invest as there are likely better returns available on the market or elsewhere within the company. Cut your loss or, as the saying goes, don’t throw good money after bad money. Losing more money, or not making as much as you could, does not reduce costs already sunk.

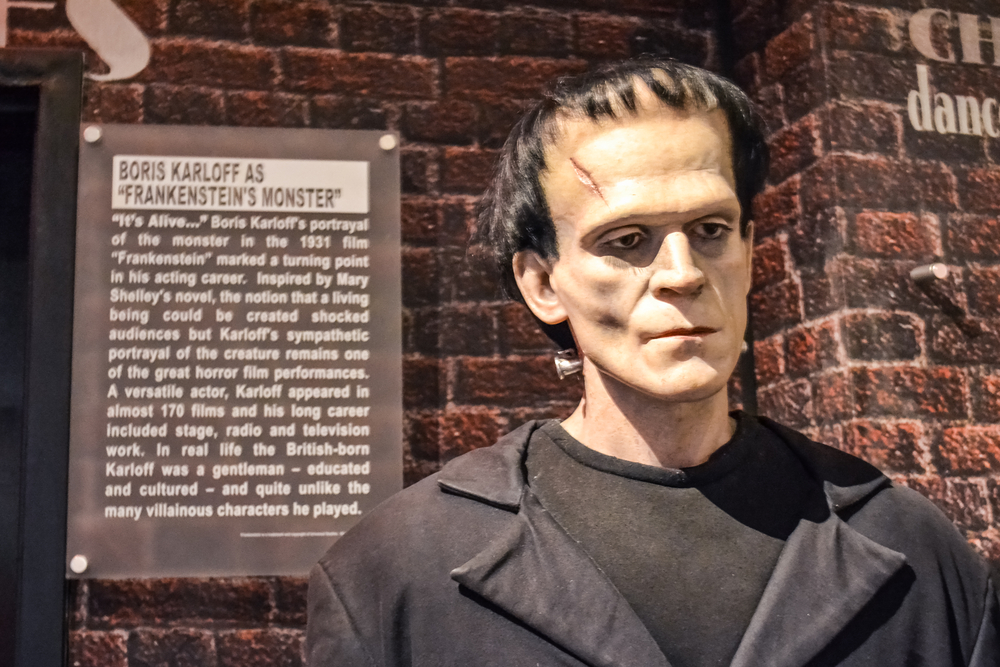

The rule applies to other types of costs and returns too. If you have spent one year creating a Frankenstein monster because (say) you needed a hunting buddy, and you discover that your creature is now likely to kill you instead, it would be bad thinking to factor in the solution the fact of “all the time I spent bringing him to life!” That time is gone forever and you won’t get it back. Regrets don’t change the past. Good decisions aim at the future.

When Apple releases its product, the company will obviously think that it will profitable even if, as the WSJ reports makes clear, fixes will have to be found and further development to be financed. But the project’s sunk costs at any point in time don’t influence the company’s decision to continue or not continue pouring money into it. If any new investment in the project is ever estimated to have no prospect of future satisfactory return, investment will stop whether “a lot” or not a lot of sunk costs have gone into it.

Why would the WSJ reporters write the sentence quoted above? I can think of four possibilities. (1) The “executives and tech analysts” consulted by the reporters are a representative sample of all executive and tech analysts, which implies that no executives or tech analysts understand sunk costs. This is very unlikely, for an executive or perhaps even a tech analyst who does not understand that would not long survive, or have survived, in competitive markets; (2) There are some executives or tech analysts who do understand sunk costs, but the reporters missed them or ignored their opinions; (3) The reporters themselves or their editor don’t clearly understand sunk costs; (4) It is just sloppy writing.

I don’t know which one, or which combination, of hypotheses #2, #3, or #4 is true, but whichever it is exposes a failure in providing the information that most of the WSJ readers pay for. It is not because most of the other medias are economically illiterate that the WSJ is justified to follow them. In my opinion, this newspaper is one of the top sources of reliable information in the world—which is why I read it regularly and thus find more occasions to criticize it (while I don’t often read Breitbart, the Chronicle of Higher Education, or the Backwoodsman). But I hope these occasions would be less frequent.

READER COMMENTS

Dylan

May 14 2023 at 2:50pm

I just finished a year inside one of the largest companies in the world in a division focused on new product development. You would be amazed at the number of times sunk costs were used to erroneously justify continuing development on a project. There was even one internal conversation we had where the sunk cost fallacy was explicitly called out by name, but the incentives were such that you couldn’t kill the project.

Even worse, the bulk of my time at the company was spent in between the announcement of a reorg and actually finding out what your new job was going to be. In the meantime, you continued to work on your old projects, knowing full well that all the work would be tossed in the garbage as soon as you were given a new job. This process repeated every 3 months on average for many of my colleagues.

I was hired to manage a project that no one, including the person whose idea it was, had any idea of why we were doing it.

One thing that seems a blind spot for many libertarians, is that the same public choice forces that they rightly call out in government, are also prevalent in corporations. Yes, competition tames some of the worst excesses. But, there’s a lot of ruin in a Fortune 500 company.

Pierre Lemieux

May 15 2023 at 4:40pm

Dylan: You are right that errors are made and nothing is perfect. As you point out in your last paragraph, what’s important to have is a system that minimizes (net) costs as far as it is possible to do it in the world as it is. One way the market does that is by minimizing agency problems: whoever is the residual claimant in an enterprise has an incentive push for maximizing profits (which means minimizing costs if the latter include opportunity costs). It is often done by changing the CEO when big changes and project write-offs need to be made. Acquisition by private equity firms is also a way to cut costs and destroy sunk-cost fetishes. (Private equity firms are not perfect either and they someties go a bit too far. GoDaddy is a current example: from a low-cost supplier with good tech support, they have become a high-cost Frankenstein with generally useless tech support and a talent for being hacked repetitively.)

THOMAS HUTCHESON

May 14 2023 at 10:48pm

Yes, what people _say_ about sunk cost do not really make any sense. I think sometimes however what they mean is that given past investments (which they may even now regret) the marginal investment costs have an acceptable return. Repainting the bedroom blue may be a mistake, but when you are almost finished it’s probably better to continue than to start over. And if you are not an economist may justify your decision with something that sounds like the sunk cost fallacy.

Pierre Lemieux

May 15 2023 at 10:16am

Thomas: That’s a good point (and I like your example). But the Wall Street Journal should still know better.

AMT

May 18 2023 at 11:13pm

This is clearly not the sunk cost fallacy. Unfortunately, you have failed to see the forest for the trees. Although the words you italicize sound like they describe sunk cost fallacy, they simply, and quite obviously only mean that the product is already substantially developed and therefore satisfactory to enter the market already.

To have sunk cost fallacy, you have to make an irrational, suboptimal decision based on your prior investments. This case is obviously the opposite. They determined that investing even more into the product before releasing it would fail to maximize profits because of the market conditions and timing. That’s certainly not “throwing good money after bad.” Sunk cost fallacy would be far more appropriate if they had a typical policy of waiting to release the product until it was ideal, and stayed with that course even though it would reduce profits; exactly the opposite situation.

Changing your strategy in order to maximize profits can never be sunk cost fallacy.

For example, consider a video game developer who pushes out their product in November to capitalize on huge Christmas demand, even though their product is significantly flawed, but good enough in their estimation. You’d be a complete moron if you didn’t consider the current quality of your product before release. See, e.g. the Cyberpunk 2077 dumpster fire.

All the WSJ have done is phrase it in a way that you mistook for sunk cost fallacy because you couldn’t understand the meaning of the full sentence in context.

Rob Rawlings

May 14 2023 at 11:19pm

You say: “or you know another investment that will bring a return of more than 50% with near certainty“

Shouldn’t you invest in both even if it means borrowing as long as the rate of interest on the loan is less than 50%? In fact shouldn’t you borrow to invest in any project you know with near certainty will provide a return greater than the interest rate (plus a small a premium to cover the loss if the “near certainty” doesn’t pan out)?

Pierre Lemieux

May 15 2023 at 10:07am

Rob: You are right. My example would avoid the real problem you point out by deleting at least the clause “or you know another investment that will bring a return of more than 50% with near certainty.” (I am toying with the idea of striking through the whole “except” clause.)

nobody.really

May 15 2023 at 1:17am

Good points. May I suggest edits for clarity?

“Suppose that you have invested $500 dollars in some project that is not producing and unlikely to produce any return, but that investing a supplementary $10 in the project will very likely bring a

net profit of $5return of $15. The $10 will thus bring a return of 50%, notwithstanding that the accounting return on the total investment will be less than1%3% ($15 / $510).”

Pierre Lemieux

May 15 2023 at 9:51am

Nobody: If I am not mistaken, a return on investment is defined as its net income (I should probably have used this standard financial term instead of “net profit”) over the investment cost. The “return” is the benefit, not the gross income. So I think my terminology is broadly correct.

nobody.really

May 15 2023 at 10:44am

Then how do you get an “accounting return” of less than 1%? You’d have to measure the net return/profit on the SUPPLEMENTAL $10 (that is, $5) compared to the TOTAL investment ($510). Why would anyone do that?

I would expect accountants to look at the TOTAL returns (or revenues, or gross profit) of $15 divided by TOTAL investment of $510, which is slightly less than 3%. Alternatively, I would expect accountants to look at SUPPLEMENTAL returns (revenues, gross profits, whatever) of $15 divided by SUPPLEMENTAL investment of $10, which is 50%.

Again, I don’t mean mean this quibble to detract from the larger point about sunk costs. But the accounting profession must endure much justified criticism; let us not add needless burden to their shoulders.

nobody.really

May 15 2023 at 11:14am

Oy, this phrasing is harder than I thought. To simplify:

If we look at SUPPLEMENTAL (or marginal) figures, I see a 50% gain: ($15 received/$10 expended) – 1. On this we agree; moreover, we agree on the relevance of this calculation for guiding a decision about whether to make the $10 supplemental investment.

If we look at TOTAL figures, I see a 97% loss–not a 99% loss: ($15 received/$510 expended) – 1.

I don’t think this disagreement hinge on terminology.

Craig

May 15 2023 at 10:44am

Sticktoitiveness, a certain dogged persistence, is also very much admired.

In my experience beware of the marginal business!

Knut P. Heen

May 15 2023 at 12:55pm

The sunk cost fallacy would not have a name if no one committed it.

In game theory, however, there is sometimes a benefit to being seen as irrational. Apple may be trying to tell their competitors that they believe in this product and that they will continue investing in it despite the lack of success so far. That may scare some potential competitors away. Would you enter a market which Apple seems irrationally committed to winning? Would you finance someone entering this market?

nobody.really

May 15 2023 at 1:30pm

To be sure, some things that appear solely as “sunk costs” may merely have underappreciated value.

An easy example appears in the tax code: Governments tax revenues, yet let taxpayers deduct “expenses”–which an economist might also count as sunk costs. Admittedly, people considering whether to launch/invest in a business count on the fact that the firm will be able to deduct expenses; if something rationally influences prospective decisions, then arguably that thing would not qualify as a sunk cost. But we see this dynamic in full flower when we observe people competing to buy up failed firms that have no remaining assets other than the fact that the firm lost a lot of money–a loss that the buyer can use to offset gains achieved elsewhere, thereby reducing net revenues and thus net tax liability.

An interesting game theoretical strategy. But as Apple signals its irrational commitment to a given market, does it invites more competition in other markets? After all, rivals will correctly perceive Apple depleting resources that might otherwise be available to compete in other markets.

Consider: NATO forces have demonstrated their resolve by shipping their arsenals to Ukraine. Does this demonstration of resolve deter China from seizing Taiwan–or does this depletion of resources invite China to invade Taiwan?

Pierre Lemieux

May 15 2023 at 4:05pm

Nobody: You write:

A sunk cost in only sunk when it is sunk. Before it is sunk, it is not sunk.

Jon Murphy

May 15 2023 at 5:59pm

I definately would. Because that means Apple will compete themselves out of existance for me. Never interfere when a competitor is making a mistake.

Just an aside, I have friends who have made themselves very wealthy by finding who is acting irrational and competing with them.

nobody.really

May 15 2023 at 1:43pm

p.s.

I’ve read a lot of essays trying to explain–and have tried to explain to others–the concept of sunk costs, yet I’ve never encountered this example before. I love it!

Craig

May 15 2023 at 1:45pm

Indeed and not only do I readily admit to having committed the error I also readily admit that I absolutely might commit the error in the future. Why? Well, its because once the fallacy is shown, its hard not to unsee it, but in real life there’s just something about it where you just won’t identify it as a sunk cost.

Right now I actually fear I might be in this fallacy with respect to a minivan with 175k miles on it and a 2004 Chrysler. Knowledge in real life isn’t quite so perfect!

Craig

May 15 2023 at 1:46pm

“The sunk cost fallacy would not have a name if no one committed it.”

Meant this as a reply to Knut’s post above….

Pierre Lemieux

May 15 2023 at 4:18pm

Craig: You mean, “it hard to unsee it,” right? (Or it’s not not-hard to not-not unsee it?)

Regarding your clunkers (I assume they are yours), the sunk costs are what you paid to buy themn and feed them. Whatever you do, nobody will reimburse these (gross) costs to you. The clunkers may still have a market value, if only for scrap, which is not sunk. It can also have a sentimental value. (You can also use them as shooting target, which is a lot of fun, especially the windows.)

Craig

May 15 2023 at 5:06pm

“Craig: You mean, “it hard to unsee it,” right? ” — Yes

If you were to poll undergrad economics students 30 years post graduation, I’d venture to say the vast majority will remember the sunk cost fallacy to some extent. Its a very notable lesson. Of course, once known, nobody will want to admit to being dumb enough to having violated it. But, I’d suggest there is something uniquely human (moth to a flame?) about it that lures humans into this trap. I have said both of the following:

1. I have too much into this to just walk away now.

AND

2. Don’t throw good money after bad money.

Are you being conscientiousness in seeing something through or displaying obstinance? Sometimes it can be difficult to tell!

David Seltzer

May 15 2023 at 4:41pm

Pierre: Often not mentioned is the opportunity cost that accompanies dwelling on sunk costs.

When I was a hedge fund managing partner, I would watch a trader fixate on a losing position rather than close it out and move on. The time spent dwelling meant he was not focused on the NEXT (marginal) market opportunity.

Craig

May 15 2023 at 5:09pm

Been there done that, know what will help people mentally? Tax loss harvesting.

David Seltzer

May 15 2023 at 5:16pm

Good point Craig!

Max R. P. Grossmann

May 17 2023 at 2:19pm

I don’t see the Wall Street Journal’s statement as at all normative.

It is a positive statement, about what might happen, not whether that is good or bad.

Supposing that the WSJ should know better, one could even view this statement as a critique by “executives and tech analysts” of Apple’s behavior: We know it, they (should!) know it, and yet we all know that management can suffer from the sunk cost fallacy.

The WSJ smartly avoids directly critiquing the use of the fallacy, and relies on readers’ understanding of irrational behavior to fill in the puzzle.

We cannot conclude the WSJ made any mistake here.

Comments are closed.