How much richer is the First World than the Third? If you simply compare nominal GDP per capita, the ratio is staggering. By this measure, Americans are over twenty times richer than Haitians. The standard view in macro, however, holds that these ratios are overstated. Largely due to non-traded goods, the cost of living is higher in rich countries. To properly compare the First World to the Third, this argument goes, one must do a Purchasing Power Parity adjustment. When you do so, the ratios shrink. The US/Haiti income ratio turns out to be more like 15:1.

The insight that poor countries aren’t as poor as they seem has a technical name: the Penn Effect. As Wikipedia puts it:

The Penn effect is the economic finding that real income ratios between high and low income countries are systematically exaggerated by gross domestic product (GDP) conversion at market exchange rates. It is associated with what became the Penn World Table, and it has been a consistent econometric result since at least the 1950s.

This all makes sense, but there’s a major offsetting factor: CPI bias. In rich countries, standard price indices fail to fully account for rising product quality, variety, and more. As a result, they overstate inflation year in, year out. (Except during Covid, where the opposite is true with a vengeance). A typical estimate of CPI bias is one percentage point per year. Might not seem like much, but over the course of fifty years, that translates to 64% higher living standards.

What does this have to do with the income gap between the First World and the Third? Simple: There are strong reasons to believe that CPI bias becomes more severe as countries grow richer.

In primitive economies, CPI bias is roughly zero. Product quantity stays the same; product quality stays the same; product variety stays the same. And when primitive economies finally get growing, consumers initially focus on acquiring a larger quantity of familiar goods. They consume more calories. They get a car. They get a TV. After a while, they get another car and another TV.

Traditional GDP measures capture such development quite well.

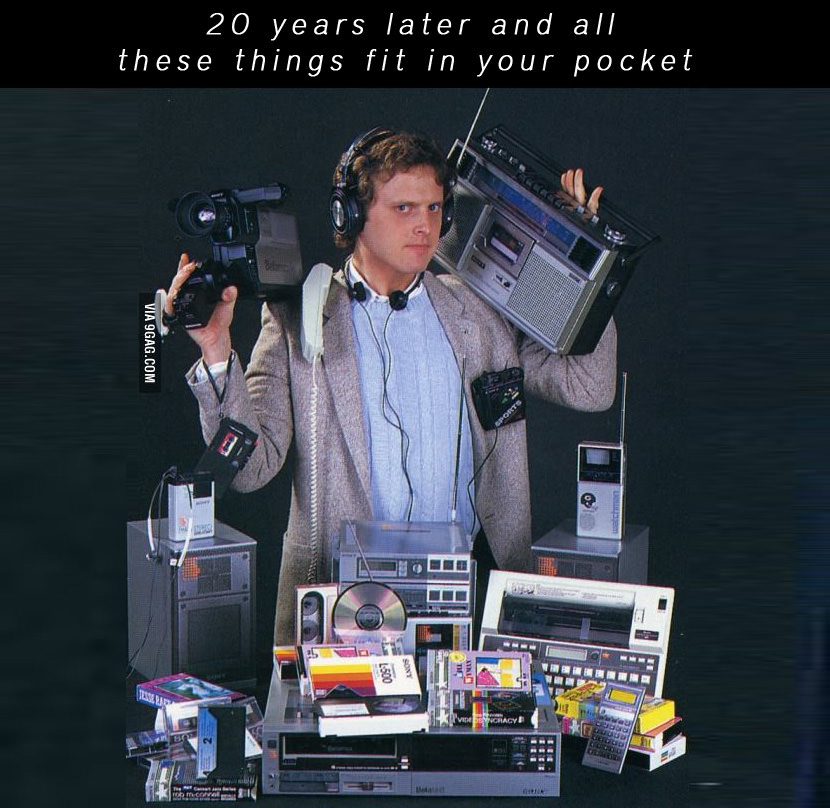

Once consumers possess an ample quantity of goods, though, they start to focus more and more on quality and variety. They don’t want more calories; they want a dozen different cuisines. They don’t want three cars; they want two cool cars. They don’t want five TVs. They want one or two mind-blowing TVs.

As far as I know, the CPI bias literature continues to neglect the evolution of CPI bias. The further you go back in the past, the harder it is to find data – and the harder it is to make other scholars care about your results. But there is every reason to think that CPI bias has been getting worse over time in rich countries. And so has the disparity between real and measured living standards. (Again, Covid aside!) Verily, our problem is not in our stuff but in ourselves.

The key qualification, however, is “in rich countries.” In the world’s poorest countries, CPI bias has probably remained very low. They’ve got smartphones now, and that’s a genuine great leap forward. Otherwise, however, living standards in the poorest countries remain ultra-low. In middle-income countries, CPI bias matters more – but still a lot less than in the richest countries. They’re materializing as we’re dematerializing.

None of this means that the Penn Effect doesn’t exist. What it means, rather, is that there’s a big, neglected offsetting factor. Once you properly account for CPI bias around the world over the last century, you could easily discover that naive estimates of the income gap between the First and Third Worlds are actually accurate. Or even understated.

P.S. If we’re so rich, why aren’t we happy? Asked and answered!

READER COMMENTS

Rafael R. Guthmann

Oct 14 2021 at 10:48am

I have lived in the US and recently and moved back to Brazil. Based on my experience the purchasing power parities are accurate in measuring the cost of living across these two countries (even the prices of my Netflix subscription, phone, and internet are closer to the PPP than to the exchange rates). So I think they are good for measuring what they want to measure: differences in living standards.

However, the advantage of the US is that since the US is richer and larger, the population there consumes a higher variety of goods and so I, as a consumer, have a greater variety of goods to choose from when I lived in the US. That difference is basically the same as the advantage of living in New York compared to living in a small town and is not captured in the PPP.

E. Harding

Oct 14 2021 at 11:32am

Could easily go the other way. Russians don’t just have cheaper internet than Americans, they have faster Internet, too.

Andrew_FL

Oct 14 2021 at 3:04pm

CPI bias is a bias in the measured *growth rate* not in the *level of prices*

Frank

Oct 14 2021 at 6:10pm

The assertion is that a CPE bias exists across countries, on account quality of products and amenities differ systematically, with better in rich countries. Thus, the Penn effect might be overestimated.

But take the Samuelson-Balassa effect that productivity differences among countries are most pronounced in the tradable goods sector. Productivity differences across countries — to encompass quality advance and amenity addition — occurs mostly in the tradables sector. I think that, similarly, quality improvement and amenities are greater in rich countries in the tradable sector. Thus, PPP estimates for the non-traded sector won’t be too bad. If so, the Penn effect does not disappear.

MarkW

Oct 18 2021 at 7:37am

They don’t want five TVs. They want one or two mind-blowing TVs.

There are no mind-blowing TVs (or rather, all modern TVs are mind-blowing). The same goes for all modern electronics. It’s not like people in developing countries have tube TVs and dumb phones — they have marginally less spectacular models and maybe unknown brands that provide nearly the same experience as those that westerners use. They watch Netflix and and make TikTok videos. Even those folks living in villages in the Amazon are also dematerializing (even before they’ve fully materialized).

Comments are closed.