I just finished writing a review of Bas van der Vossen and Jason Brennan’s recent book, In Defense of Openness: Why Global Freedom is the Humane Solution to Global Poverty. (It should be in the Spring issue of Regulation.) The economics of this book is good, but here is a questionable minor point. The authors write:

Suppose Jason typically buys American pick-up trucks, because he wants to avoid the 25% tariff on imported trucks.

This is not correct. The tariff on light trucks—the so-called Chicken Tax, which I discussed in a previous post—cannot be avoided by buying domestic. In the general case, as I explained in another blog, a tariff equally increases the price the imported good and of its domestically-produced equivalent. Domestic producers want the tariff precisely in order to be able to increase their prices and sales. They will charge what the market will bear, that is, as much as the sellers of the imported good charge tariff included.

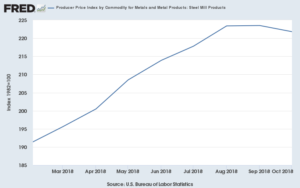

Let me illustrate with steel. The 25% steel tariff imposed by the U.S. government on different countries between March and June confirms the theory. The price of all steel, foreign and domestic, has increased in the United States, as can be seen from a Wall Street Journal report of November 23 (“Steel Tariffs and Hot Economy Take Toll on Infrastructure Projects”):

Through October, the price of diesel fuel was up 27%, asphalt-paving mixtures were up 11.6% and steel-mill products were up 18.2%, all compared with a year ago, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Tariffs of 25% on steel imported from China and other countries imposed in June have given domestic steel makers leverage to raise their own prices, say analysts. …

Bill Boynton, a spokesman for the New Hampshire Department of Transportation, said the state has seen a surge in steel prices since this summer of about 30%. The Ohio Department of Transportation paid 19.1% more for structural steel in September, compared with a year ago.

The price increase calculation depends on the dates chosen. Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show an increase in steel prices of 14% since February, the month before the tariffs were announced in early March (see the chart below, and click on the image to view a larger format). Over the same period, data from the SteelBenchmarker show an increase of 10% in the U.S. price of hot-rolled band (a benchmark steel output), while the world price decreased by 11%. These data are consistent with an increase in American steel prices of 15%-20%.

The difference with the tariff percentage should be accounted for by the fact that the tariff hits steel before marketing and distribution costs, by timing factors, possibly by terms-of-trade effect (tariff-induced lower U.S. demand exerting downward pressure on the world price exclusive of the tariff), and other influences.

Back to pickup trucks. For the same reasons as in steel, we would expect the 25% tariff on pickup trucks (in force for more than five decades) to translate into an equivalent increase (minus marketing and distribution cost) in the price of both imported and domestically produced pickups. It is not true that the American consumer has a choice between what he considers equivalent pickups at two different prices, with imported ones priced higher than domestic ones; he has to pay the same price for both. This is not surprising: no consumer (except a minority willing to pay for their political or esthetic preferences) would pay a premium for a Japanese over an American pickup with equivalent features and options (including brand reputation).

Note however an important difference between the pickup market and the steel market. In the former, the 25% tariff is so high that it discourages all imports and gives the entire domestic market to domestic manufacturers, the Big Three. No foreign-made pickups are exported to the United States on a commercial basis (see a list of foreign-manufactured pickups at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_pickup_trucks). The only way for a foreign manufacturer to get around the prohibitive tariff is to establish manufacturing facilities in the United States or elsewhere in the NAFTA zone, as Toyota, Honda, and Nissan have done. This increases domestic supply compared to a situation with no imports and with no manufacturing facilities by foreign manufacturers in the NAFTA zone, and pushes domestic prices back down, but not all the way to the world price.

How do we know that foreign manufacturers’ facilities in the United States don’t push back the domestic price to the world price–in which case the tariff would have no effect on price? Because if manufacturing in the United States did not cost more than elsewhere, foreign pickup manufacturers would have produced their pickups in the United States without the tariff, and would not need a tariff to continue doing so. Obviously, there are some costs in the United States and other NAFTA countries that make manufacturing certain lines of pickups here more expensive. In America and Canada, powerful trade unions come to mind; in Mexico, it may be lower productivity.

The prohibitive pickup tariff thus imposes to American buyers a premium that is positive but below 25%. More data and analysis would be needed to provide a narrower estimate, and I am not aware that this exercise has been done; but I suspect the premium is closer to 25% than to 0%. Look at it another way: the premium is equal to the additional price the Big Three can charge because they face less competition thanks to the prohibitive tariff. But whatever its exact value, the premium charged to consumers is the same for all pickups sold in America.

I don’t think this conclusion is changed by the fact that foreign producers are into smaller pickups than the full-size ones that most Americans buy (see Anton Wahlman, “GM Gains 2% Market Share And Takes U.S. Pickup Truck Sales Crown From Ford,” Seeking Alpha, July 9, 2018). Many foreign producers would adapt their offerings to the American market if they could access it without a prohibitive tariff. The adaptation would take some time for full-size pickups, but compact pickups would rapidly start competing. Supply responds to demand. More competition means lower prices.

READER COMMENTS

Benjamin Cole

Nov 30 2018 at 7:30am

Still, it is interesting the best pick-ups in the world are built in America.

The development and re-development of economies is a nuanced topic, and perhaps not resolved easily by free-trade theories.

Matthias Goergens

Nov 30 2018 at 10:24am

The best pickup trucks by what metric? And if they are so great, why do they need protection to compete?

(Also keep in mind that economically (low) price is a big part of what makes products good.)

Benjamin Cole

Nov 30 2018 at 8:23pm

Matthias—

We must make policy for the real world and in the real world there are sometimes sui generis situations, which are not anticipated by theorists.

Why does US manufacturing need “protection”? Because we live in a world of very large dirigiste economies, where governments provide manufacturing with free land, free capital and other free assistance.

The choice advocated by so-called free traders is to move the entire manufacturing base to China, in which case we would sell even more assets or go deeper into debt to pay for imports.

In today’s world industrial location is not determined by macro economics or true comparative advantage, but by government actions.

Remember, when free-trade theory is sacralized, it becomes free-trade theology.

Multinationals can pour unlimited funds into media, academia, think tanks, lobby groups, trade associations, and even political campaigns to make sure free-trade theology is what frames conversations about international trade.

The cozy relationship between multinationals and the increasingly repressive Communist Party of China is something to behold. Who would ever think the US Chamber of Commerce would become a mouthpiece for Beijing Commies?

artifex

Nov 30 2018 at 9:13pm

If other countries want to give us stuff for free, let them.

Thomas Sewell

Nov 30 2018 at 9:42pm

You must really hate the idea of Santa Claus. He supposedly has all sorts of North Pole workshops which send products to the U.S. so subsidized they are totally free to the recipient, with all the costs borne by the North Pole residents!

Benjamin Cole

Nov 30 2018 at 9:55pm

Thomas/Artifex:

There is no such thiing as a free lunch.

The Chinese do not give us product. They sell us product at subsidized rates. They use income from imports to buy US assets, technology, or bonds.

BTW, these huge inflows of capital cause asset bubbles, especially in housing.

https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr541.pdf

http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/ESR/Issues/2018/07/19/2018-external-sector-report

When the asset bubbles pop—see 2008—there is quite a bit of pain to follow.

Jon Murphy

Nov 30 2018 at 8:34am

Excellent post. Another important thing that your discussion here highlights is that a tariff is always paid for by the consumers of the domestic nation. Some incorrectly interpret the lower world price as the tax being paid (at least partially) by foreigners, but that is not the case.

There are also some interesting implications here viz. using a tariff as a means to get trade “concessions.” A domestic tariff means higher domestic prices. Domestic firms come to rely on those higher prices; any gains they get initially from the higher prices are transitional and they capitalize those gains. In other words, the “extra-normal” profit these firms might enjoy from the higher tariff giving them monopoly power goes away and becomes just normal profit (this is especially true when considering the Second Law of Demand, which indicates that as prices stay relatively high, demand becomes more elastic, as well as Anne Krueger’s work that monopolists typically fail to capture all of their extra rents anyway because of rent-seeking activities). Thus, those firms would suffer very real losses should the tariff be repealed or reduced. This would make removing the tariff, even if the other nation should acquiesce, politically difficult.

Matthias Goergens

Nov 30 2018 at 10:32am

It’s a good rule of thumb that tariffs are paid for by the customer, but it’s not an iron law.

A tariff is just a special kind of tax on a transaction that spans borders. And normal economic theory about tax incidence applies.

Basically, the parties involved bear the economic cost in relation to how inelastic their demand respectively supply is.

(As an exercise, you can try to think about who would pay for a tariff on exports. It’s generally not the importing customer.)

Jon Murphy

Nov 30 2018 at 10:50am

Indeed the normal tax instance applies. That’s my point. The consumer pays in a higher price regardless. The producer only through reduced production. The cost of the tax is borne by the consumer. It is not a tax paid by foreigners.

Pierre Lemieux

Nov 30 2018 at 11:17am

@Matthias Goergens: Yes, the same theory applies, but with an infinitely elastic world supply curve from the point of view of the importing country, which makes all the difference. Think about the standard graph with domestic demand, domestic supply, and world supply/price as a horizontal curve. (If world supply is not perfectly elastic, then you have a terms-of-trade effect, which I mention as a special case.) This, I think, also solves the apparent contradiction you raise in your final parenthetical remark.

Benjamin Cole

Nov 30 2018 at 10:30pm

Pierre:

An odd little side-note from the grubby real world:

China has been expanding export tax rebates on product sold to the US, to counterbalance higher US tariffs.

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-economy-tax/china-to-increase-export-tax-rebates-on-397-products-idUSKCN1LN12F

So, in this case, we can posit taxes formerly paid on China exports are instead now collected in the US as tariffs, and consumers see no price change.

Of course, China has no free press (or freedom of any kind), and is opaque, so we do not really know how complete, or even excessive, the China export rebates might be, or if other subsidies are magnified.

But it certainly appears China will “eat” US tariffs—meaning a boon for US taxpayers.

This is an amazing chart.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/B235RC1Q027SBEA

Pierre Lemieux

Dec 11 2018 at 9:36pm

Thanks, Bejamin, I had seen this interesting FRED chart. But since prices have increased in the US (there might be exceptions, but I still have to put my finger on one), the implication is that Chinese producers have not received compensating subsidies, and the tariffs/taxes have been paid by US consumers (and, to repeat, also on domestically produced equivalents). Remember: foreign exporters pay the tariff to the Treasury, and are reimbursed in higher prices (although their sales decrease). As for export subsidies, they are generally a bad idea for the foreign taxpayers forced to offer them because they thereby pay the foreign tariffs instead of the consumers of the tariffing country. Moreover, subsidies can have perverse terms of trade effects. All that is in the grubby world of trade theory: it’s worth having a look and getting one’s mind dirty.

Bill

Dec 6 2018 at 11:57am

Jon, good comment. Tullock’s “Transitional Gains Trap” paper comes to mind.

Rob Rawlings

Nov 30 2018 at 10:29am

‘we would expect the 25% tariff on pickup trucks (in force for more than five decades) to translate into an equivalent increase (minus marketing and distribution cost) in the price of both imported and domestically produced pickups.’

I find this a little non-intuitive. If no trucks were produced abroad before its introduction then a 25% tariff would have no effect. If all trucks were produced abroad then it seems likely that much of the 25% would be added to price. I would therefor expect the actual short-term increase in price to be on a scale of between 0% and 25% depending upon (among other things) the % of the goods that is imported. Of course the tariff will reduce this %, but I doubt it will generally do so by more than a relatively low % of total quantity sold.

In addition while the tariffs may allow local producers to increase profits in the short term, these additional profits will attract new entrants to the market (and for existing producers to expand) until these above average profits are eliminated. I would expect the final price (using reasonable assumptions about the inputs used to produce the good) to be not much higher than the initial price, and certainly closer to 0 than 25%.

Pierre Lemieux

Dec 1 2018 at 6:48pm

Rob Rawlings: You are right to introduce abnormal profits and time in the analysis. But, I don’t think it changes my conclusions.

(1) Even if a prohibitive tariff is levied in the absence of imports, it will increase prices as future opportunities for foreign producers develop. Domestic producers will rapidly supply any increase in domestic demand. In the case of the Chicken Tax on “light trucks,” it did respond to actual and potential competition from Europe (I understand that the Volkswagen minibus was one of the actual competitors).

(2) Your argument on the elimination of abnormal profits is correct. This is indeed what happened: foreign competitors established manufacturing facilities in the U.S. in order to exploit abnormal profits. But since they hadn’t produced here before, it suggests that only an increase in price (rendered possible by the tariff) could now justify them to do it. (Note also that domestic producers also need a price increase to produce more, for they presumably have increasing marginal cost and a positively-sloped supply curve.)

Rob Rawlings

Dec 2 2018 at 10:59am

Thanks for the reply!

I agree that tariffs will lead to an increase in domestic price but think that this increase will be driven more by the productivity differential between foreign and domestic production (with the tariff acting as an upper bound on any price increase).

If one assumes that the producers of a good are price takers for all its inputs and that foreign producers are (say) 15% more efficient at producing the good then a 25% tariffs may well eliminate imports Other things equal I would predict that the price change in this scenario would be around 15%.

If the producers are not price takers for inputs then the increased production will also increase input costs leading to addition price increases. In this case the 25% tariff will tend to put an upper ,limit to the price increase. If the production costs (and price) would increase by greater than 25% then it will make sense to continue to import the good.

MarkW

Dec 2 2018 at 1:20pm

I suspect the premium is closer to 25% than to 0%

I’m pretty sure it’s much closer to 0 than 25%. That’s because foreign automakers have chose to manufacture many kinds of vehicles in North America that are not subject to the chicken tax and have even, on occasion, exported some of their U.S. production:

https://www.usatoday.com/story/driveon/2014/01/28/honda-exports/4956205/

They would not do either of those things if North American production was prohibitively expensive.

Pierre Lemieux

Dec 5 2018 at 10:24pm

Note: I did not say that production in North America is prohibitively expensive. I said that the 25% light truck tariff is.

MarkW

Dec 6 2018 at 5:44pm

Well, you suggested (I thought) that Americans were paying closer to a 25% than 0% premium on pickup trucks because of the chicken tax (specifically because the threat of the tax protects U.S. manufacturers from competition). But Toyota, Nissan, and Honda have moved pickup production into North America to avoid it. So if Americans are paying any premium at all for pickup trucks it must be because NA production is expensive (since nobody’s actually paying the chicken tax). How much of a premium are American customers paying because these trucks are built here instead of abroad? Is there any reason to think it’s more than the premium they’re paying (or not paying) for autos and SUVs assembled in NA? And remember that full-sized pickups like the Toyota Tundra and Nissan Titan are North-America-only models (other markets really aren’t interested in pickups that are so large).

I’m not writing in support of the chicken tax in any way, but I do think that manufacturers have, over time, worked around it so effectively that any actual premium that American consumers are paying for pickups is negligible (and nowhere near 25%)

Pierre Lemieux

Dec 11 2018 at 10:06pm

What seems to have happened (taking due notice of Rob Rawlings’s addendum) is the following:

1) American auto manufacturers were threatened by imports of foreign light trucks and asked for a tariff.

2) The (prohibitive) Chicken Tariff was imposed.

3) Imports of foreign light trucks virtually stopped.

4) These imports were replaced by domestic production, at higher cost because the supply curve has a positive slope (increasing marginal cost, at least in the short run) and the tariff allows domestic producers to sell their higher-priced trucks profitably.

5) Domestic producers made abnormal profits (and trade-unionized workers shared the loot).

6) Foreign truck manufacturers entered the American market to share these abnormal profits caused by higher domestic prices. (Without the tariff, they would have continued to produce at lower cost from home and simply exported to America.)

7) Supply (not quantity supplied–this had happened before) increased and profits returned to their normal level.

8) The new supply from foreign manufacturers’ US plants, however, did not push prices down to their former level (what they would be without the Chicken Tariff), because manufacturing a truck in the US costs more (supply curve higher).

9) Consequence: consumers end up paying between a premium equal to this additional cost within the 25% tariff (or, more exactly, within the part of the 25% that hit the imported trucks excluding distribution and marketing).

Comments are closed.