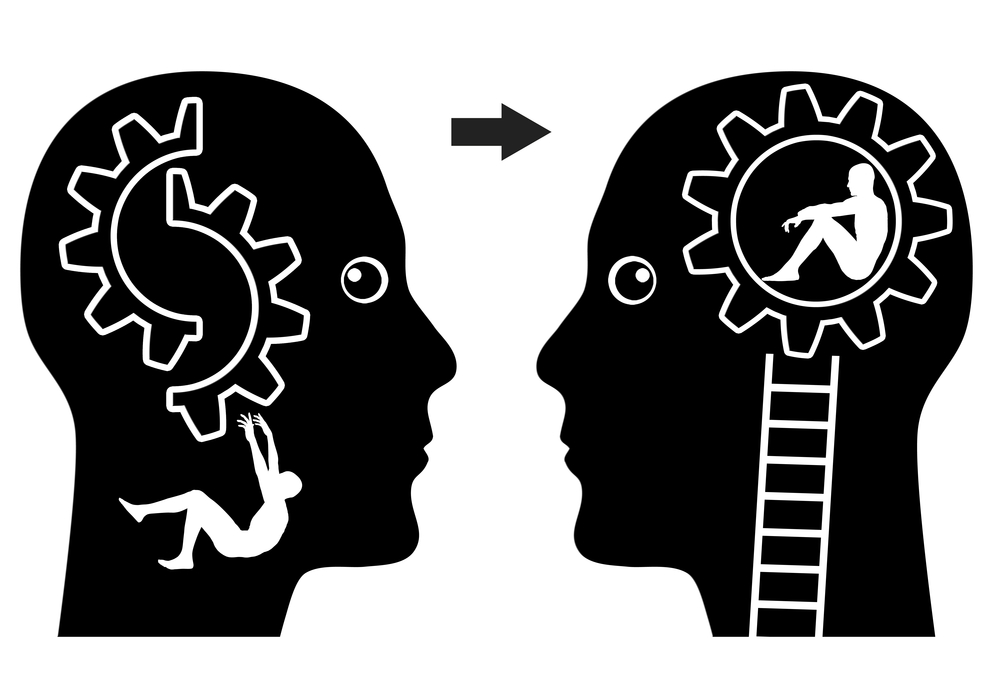

There has been a long running debate going on between Bryan Caplan and Scott Alexander on how to understand mental illness. Caplan argues that mental illness doesn’t really exist. Very briefly, Caplan uses the distinction between budget constraints and preferences in consumer choice theory to analyze the behavior of the “mentally ill.” A key component of his view is what Caplan calls the “gun to the head test.” If you put a gun to the head of a diabetic and told them to normalize their insulin levels (without medical intervention), they wouldn’t be able to do anything differently. But if you put a gun to the head of someone with an overeating disorder and ordered them to put down the doughnut, they would be able to do so. This, Caplan says, shows the overeater is capable of doing otherwise while the diabetic is not. Therefore, the diabetic faces a constraint and has a true illness, whereas the overeater just has a really strong preference for eating lots of food, and therefore compulsive overeating is just fulfilling a preference and doesn’t qualify as an illness or disorder.

Scott Alexander replied that consumer choice theory is inadequate for understanding or classifying mental illness for a variety of reasons. Bryan offered a rebuttal, Alexander came back with a rejoinder, and now Caplan has responded yet again. I recommend reading the entire exchange for full context. While I admire both of these thinkers greatly, I think Alexander has the stronger arguments.

At the highest level, I think Caplan gives far too much credence to the consumer choice model he uses. Economic models are useful tools, but like all models in social science, they are useful because they are simplifications. The map is not the territory, and the model is not reality. And any model of human behavior that does not perfectly and completely describe reality (which is to say, all of them) can end up being more confusing than enlightening when misapplied.

Consider the compulsive overeater. Overeating has many potential causes, of course, but one of these causes is leptin deficiency. Leptin is a hormone that regulates hunger and desire to eat. In his book The Hungry Brain, Stephen Guyenet describes it in the following way:

Yes, such a person might very well put down the doughnut (or trashcan scraps and uncooked fish sticks) if you held a gun to their head at any given moment. But so what? Their behavior still seems to me like it’s much better described as a budget constraint caused by low leptin levels, and not as someone merely fulfilling their unusual and socially disapproved preference to eat themselves into oblivion.

Another reason I find the gun-to-the-head test unimpressive is that it contains a hidden premise that I don’t think can be justified. Here’s how Caplan describes this test in his most recent post:

The hidden premise behind this test is the idea that any behavior someone can engage in (or refrain from) while under extreme, life-threatening duress is therefore something they are capable of engaging in (or refraining from) at all times, for their entire life. But I don’t see any reason to believe this is true. Consider, for example, the case of mothers who have lifted cars off the ground to save their trapped children. Suppose a week before that happened, you asked these women to deadlift 500 pounds in the gym and found none of them could do it. Yet, a week later, they lifted considerably more weight than that in order to save their child. I’d say this is just a case of showing that what a person is capable of doing is different in normal circumstances and in extreme circumstances.

As I understand it, Caplan’s argument would commit him to saying that since there was at least one “incentive in the universe” that made them lift such immense weight, that shows they must have been able to lift such immense weight all along, and their inability to pull off a 500-pound deadlift the prior week wasn’t a real constraint, it was just them expressing their preference for not lifting heavy weights. That’s what a straightforward application of consumer choice theory would imply, but that only shows the limits of consumer choice theory. Yes, incentives did matter in their car-lifting feat, but that does not imply the inability to carry out such a feat in normal circumstances is therefore “voluntary” in any meaningful or interesting way, nor does it imply that the genuine inability to deadlift 500 pounds the week prior was actually just a preference.

(As an aside, Alexander is also unimpressed with this test, offering to “tell [Caplan] about all of the mentally ill people I know about who did, in fact, non-metaphorically, non-hypothetically, choose a gunshot to the head over continuing to do the things their illness made it hard for them to do. Are you sure this is the easily-falsified hill you want to die on?” But notice the asterisk above in Bryan’s description of his test. That asterisk leads to footnote where Caplan implies that even if someone does take a gunshot to the head over altering their behavior, that still wouldn’t falsify his argument, because “incentives don’t matter does not imply involuntariness, though it leaves the possibility open.” When every possible outcome of one’s hand-picked method of testing their view can still be interpreted as compatible with that view, then it’s not a very impressive test, and holding it up as some sort of ace-in-the-hole for the argument doesn’t inspire confidence.)

People are sometimes temporarily capable of things in extreme duress they couldn’t achieve in normal circumstances. This is both common sense and widely known. This aspect of human behavior doesn’t fit into the simple consumer choice model of constraints and preferences – and that’s okay! Consumer choice theory isn’t and shouldn’t be treated as a theory-of-everything, meant to explain and classify all forms of human behavior. It’s just a useful oversimplification for understanding a small subset of human life.

In the closing paragraphs of Caplan’s most recent post, he cites an argument from someone named Emil Kierkegaard making the case that homosexuality is best understood as a mental disorder – a position Caplan disagrees with, arguing that homosexuality is simply a preference. Caplan closes out by saying:

In response to this, I would quote Ralph Waldo Emerson’s observation that “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines.” To go back to my observation in the beginning, economic models – including consumer choice theory – are not perfect descriptors of all reality. And when your model doesn’t fully capture reality, forming all your beliefs to be perfectly consistent with that model is not automatically a virtue. The understanding we gain of the world from any of our models will always be limited and partial. In light of this fact, being a little inconsistent will often be more truth-preserving than perfect consistency. And on this topic, I find Scott Alexander’s less-than-perfect consistency far more truth-preserving than the total consistency of either Caplan or Kierkegaard.

READER COMMENTS

Kevin Corcoran

Jun 29 2023 at 3:32pm

Of note!

By the inevitable nature of things, yesterday, before this post went live, Scott Alexander came back with yet another response of his own to Bryan Caplan’s latest post, so my summary of the exchange above is already one step behind. Alexander’s latest reply can be found here.

Jon Murphy

Jun 29 2023 at 3:57pm

Caplan’s “gun-to-the-head” test is an example of something that drove me and my classmates nuts in his PhD Econ class. Bryan is an extremely binary thinker: if it’s not 100% true all the time, then it is false. He loved to ask true/false questions on exams and many a student would get the question wrong because it was only true 99% of the time (and thus false).

Of course, none of this is to say Caplan was a bad teacher or economist. I’ve learned a lot from him. But he tends to project computer logic onto everything and everyone. Consequently, he sometimes misunderstands unusual situations (like mental illness).

Kevin Corcoran

Jun 29 2023 at 4:32pm

I would agree that Caplan is an excellent teacher – I took his labor economics course and public choice course. And I’ve learned a lot from him as well, in the classroom but also outside it, from his blogging and his books. I do have areas of strong disagreements with him as well, of course, but I also have strong disagreements with myself from a few months ago too, and I know past me wasn’t all that bad.

Dylan

Jun 30 2023 at 6:36am

From a few months ago? I feel like half of my waking life is listening to my internal narrator argue with itself.

steve

Jun 29 2023 at 9:42pm

If you have worked a lot with the mentally ill you know that his claims about people being able to stop if you put a gun to their head is so nonsensical its hard to believe anyone would make the claim. True of some but not true for a lot. Then claiming that even if they do shoot themselves it doesnt prove anything is too much. Heads I win tails you lose.

Caplan is bright, he is interesting and will make you think. That said part of his schtick is saying controversial, attention getting things then engaging in odd arguments with weird analogies, often with black and white extremes, to try to prove his claims. This is one of those times and you should let him argue with himself.

Steve

Scott Sumner

Jun 30 2023 at 1:35am

The entire debate seems uninteresting. A debate over how to treat the “mentally ill” would be interesting, but the answer to that question does not hinge on what label we attach to this group of people.

robc

Jun 30 2023 at 8:53am

I think it was more important when involuntary hospitalization was a bigger deal.

Scott Sumner

Jun 30 2023 at 2:32pm

Really? It’s not obvious to me that involuntary hospitalization would be justified by the fact that a certain condition is defined as an illness. We don’t force the physically ill into hospitals. It seems like the argument (valid or not) is based on the perception that these people pose a risk to themselves and those around them. But that perceived risk doesn’t hinge on the label we attach to their condition.

BS

Jun 30 2023 at 1:53pm

It’s not as if the idea of incentives hasn’t occurred to anyone, ie. “the patient has to want to change”. The problem exists regardless how the definition of “illness” is arbitrarily changed.

Physecon

Jul 3 2023 at 2:51pm

Indeed. In some ways this is similar to the debate about what defines a “recession” as you wrote about recently. It’s not really important what label is applied where. It’s important to think about how people are treated.

nobody.really

Jun 30 2023 at 10:55am

I sense the point of the Bryan Caplan/Scott Alexander debate is to illustrate that the boundary between volitional/not volitional is weaker than a lot of Enlightenment thinking (and our legal system) would imply.

Daniel Kahneman, winner of the Nobel Prize in Econ, developed the idea of Type 1 and Type 2 thinking: One refers to the classic, deliberative model of thinking we tend to focus on, while the other refers to the quick, automatic processes that run in our mental background, making 90% of our decisions. Yes, it’s possible to consciously overrule our automatic processes on this or that occasion–but it’s mentally taxing, and humans face a budget constraint on how they allocate their energy. In experiments, if you offer calm, resting people snacks they may choose a healthy apple–but if you offer them a snack while they’re stressed or working on a math problem, they reflexively grab the doughnut. Perhaps Caplan would explain this change in behavior by saying the people under stress systematically adopted different tastes and preferences.

Here I also think of microaggressions: Some people assume that people have a stable character that manifests under all circumstances. But others conclude that people have finite energy, and if you deplete your energy coping with regular negative feedback you will find yourself less able to cope with other stressors than people who do not live in a constant state of depletion. Observers who ignore these differences may be unable to explain differences in behavior/outcomes for members of dominant and subordinate groups, and be left to conclude that the differences must reflect differences in tastes and preferences.

Mactoul

Jun 30 2023 at 10:00pm

I think Emil Kierkegaard classed homosexuality as a sexual targeting disorder. Not a mental disorder.

rsm

Jul 11 2023 at 12:24pm

Is the person holding a gun to someone’s head over donuts and insulin the real mentally ill one?

Comments are closed.