Kevin Corcoran recently did a post discussing the distinction between being wrong in theory and wrong in fact. Here I am interested in another situation, the case where theory matches reality quite closely, but people are reluctant to accept the implications of that fact. For instance, basic economic theory suggests that higher tax rates ought to reduce hours worked. Europe has higher tax rates than America and considerably lower hours worked each year. But many people seem reluctant to accept the straightforward implications of those facts.

The Economist has a very good article on this topic:

Edward Prescott, an American economist, came to a provocative conclusion, arguing that the key was taxation. Until the early 1970s tax levels were similar in America and Europe, and so were hours worked. By the early 1990s Europe’s taxes had become more burdensome and, in Prescott’s view, its employees less motivated. A substantial gap persists today: American tax revenue is 28% of GDP, compared with 40% or so in Europe.

Notice that Prescott relies on two types of evidence, both cross sectional and time series. That makes his claim much more persuasive than a simple comparison of two places at a point in time. And yet many people remain reluctant to accept the obvious implications of these facts.

The article does present one empirical study that suggests that work disincentives from high taxes might be rather modest:

A recent study by Jósef Sigurdsson of Stockholm University examined how Icelandic workers responded to a one-year income-tax holiday in 1987, when the country overhauled its tax system. Although people with more flexibility—especially younger ones in part-time jobs—did indeed put in more hours, the overall increase in work was modest relative to that implied by Prescott’s model.

Again, this result is not at all surprising. Because of the “collective-action problem” aspect of work structure, one would expect the short run elasticity of labor supply to be much lower than the long run elasticity. Decisions on work schedule are generally made at the company level, and to some extent even at the societal level (as with things like school schedules, which must be coordinated with work schedules.) Notice that the elasticity was higher for part-time younger workers, who face less of a coordination problem.

How can we explain the reluctance to accept the obvious implications of a theory? A few more examples will help to illuminate the sources of bias:

1. Theory suggests that higher levels of CO2 should raise global temperatures due to the “greenhouse effect”.

2. Theory suggests that injecting lots of money into the economy should cause price inflation (i.e., reduce the purchasing power of a single dollar bill.)

It would be quite surprising if more CO2 did not cause global warming, or if large money injections did not cause inflation. And yet, I often meet people who disagree with these claims. They might argue that global warming is an unproven theory, or that inflation is caused by corporate greed. Why reject evidence that almost perfectly matches standard theory? What’s going on here?

I notice that people who believe in the corporate greed theory of inflation also tend to have left wing policy views, whereas people who are skeptical of global warming tend to have right wing policy views. Perhaps this provides a clue as to why so many people are skeptical of the claim that high taxes discourage work effect.

Suppose you are someone who favored a large welfare state, for a wide variety of reasons. In that case, you might be resistant to accepting empirical data that suggests negative effects from high taxes. From a purely logical perspective, this doesn’t make much sense. It is certainly possible that a welfare state is beneficial despite leading to a reduction in per capita GDP. Perhaps the extra leisure is worth the hit to national income.

Unfortunately, when people have strongly held policy views, they became more like lawyers and less like scientists. They seek out any evidence that seems to strengthen the case for their policy preferences and discount evidence that weakens the case for their policy preferences.

Political bias is not the only factor that leads people to reject the implications of economic theory. It is also the case that many economic theories are counterintuitive. For instance, most elasticities tend to be higher than what one would expect if one relied on introspection, i.e., on “common sense”. Thus even people with so-called “addictions” such as smoking or illegal drug use are often surprisingly responsive to price signals.

Many people probably have trouble visualizing how higher taxes would lead them to work fewer hours. They might think, “With higher taxes, I’d need to work longer hours to pay my bills.” Their mistake is in not recognizing that tax revenues don’t disappear, they are recycled back in the form of benefits to those who consume more leisure. This is what economists mean by an “income-adjusted elasticity of labor supply”.

To summarize:

1. When theory suggests that X is true.

2. And when empirical evidence tends to confirm theory.

Be very careful before rejecting the claim that X is true.

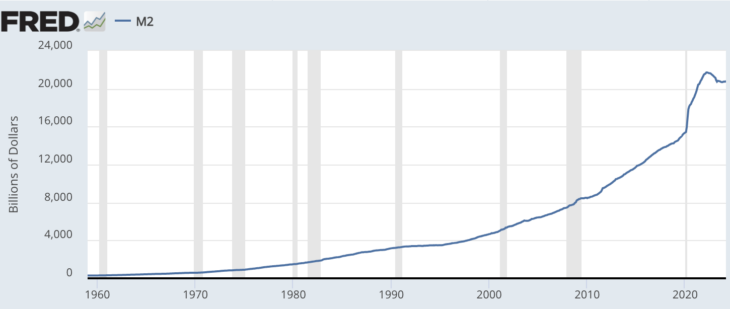

PS. Suppose you went back in time and showed David Hume the following graph for the M2 money supply:

If Hume were asked what he thought happened to inflation during the early 2020s, how would he have responded? Then suppose you told Hume that many people now blame “corporate greed” for the high inflation of the early 2020s. How would that information impact Hume’s view of progress in the field of economics in the 270 years after he developed the Quantity Theory of Money?

READER COMMENTS

David Seltzer

May 28 2024 at 5:52pm

Scott: Nice post on economic reasoning supported with applied statistics

Richard W Fulmer

May 28 2024 at 6:21pm

Inflation is an indirect tax. Given that Social Security is indexed to inflation and many, if not most, welfare programs are not, would you predict that higher inflation would lead older workers to retire early, and welfare recipients to enter, or reenter, the workforce? If so, would that imply that the workforce would, on average, become less experienced and less skilled and, therefore, less productive? Are there empirical data supporting or refuting such predictions?

Mactoul

May 28 2024 at 9:54pm

Science is quantitative. It is insufficient to say just CO2 increases temperatures. One must say how much increase. And the real world consequences of global warming depend on this number which is still in dispute.

Scott Sumner

May 29 2024 at 1:59am

How does this comment relate to my post?

Kevin Erdmann

May 28 2024 at 10:32pm

I’m surprised you used the m2 example since it is a mirror image of NGDP. I assume that Hume would expect that nominal spending jumped above trend at the same time that m2 did, rather than jumping below trend. So it seems like a case where the outcome is a bit more complicated than his intuitions, in spite of getting the right answer.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1ogqK

Scott Sumner

May 29 2024 at 1:56am

Hume argued that money affected the economy with a lag, but in this case the lag might have been longer than expected. Nonetheless, looking at the early 2020s as a whole, it certainly conforms to Hume’s model.

Philippe Bélanger

May 28 2024 at 11:49pm

What does it mean to say that “theory” suggests something? There is no one single theory; there is an infinity of them. And the mere fact that something is suggested by a theory doesn’t give us any reason to believe it.

One also wonders what would have been Hume’s prediction if we have shown him a graph of the monetary base from 2008 to 2012.

Scott Sumner

May 29 2024 at 1:58am

“One also wonders what would have been Hume’s prediction if we have shown him a graph of the monetary base from 2008 to 2012.”

What if you also told him that the Fed had suddenly begun paying interest on bank reserves.

Philippe Bélanger

May 29 2024 at 7:55pm

I am skeptical of the idea that the payment of interest on reserves explains why QE hasn’t been inflationary, partly because it is a theory that can’t account for Japan’s experience. In the last 10 years, Japan’s monetary base has increased more than six fold and for most of that period, interest rates on reserves were negative. Yet inflation has hovered around 1%.

Scott Sumner

May 30 2024 at 4:54pm

I agree that it doesn’t apply to Japan, but it was a factor in US policy during 2008. In any case, I would never argue that there is a close correlation between the base and the price level at zero interest rates.

But it’s sort of bizarre to blame “greed” for recent inflation when there was such an expansionary monetary policy by almost any metric. Was there no greed in the 2010s?

Philippe Bélanger

May 31 2024 at 8:38pm

“Greedflation” is a terrible theory, I agree. (It is basically untestable. How do you measure greed? And why did firms all become greedy at the same time?) I was more taking issue with the idea that our recent exprience vindicates the quantity theory as expounded by Hume.

Peter

May 29 2024 at 2:17am

My question here is IF that holds true, why is it Americans work the same 40 hours in each state even though tax rates vary greatly between them. It would suggest low tax Texan’s would work less hours than high tax Hawaiian but I’ve seen no evidence of that and instead, the exact opposite. Large numbers of Hawaiians, even middle class, have a full time job and one or two part time jobs as well.

Also can you explain this one using a concrete example as it applies to the upper middle class

Curious what government benefits a German doctor receives for his reduced hours. Likewise what government benefits does a plumber in Taxachusetts receive over his Missouri peer. Not saying your wrong here, I just ain’t groking it.

Peter

May 29 2024 at 3:59am

Texans would work more hours, not less than Hawaiians given the tax rates. Sorry transposed them in writing.

Dylan

May 29 2024 at 6:59am

Interesting thoughts, but not sure the data backs wither you or Scott up at the state level. It looks like Texans do work longer hours than Hawaiians. But Californians work almost as much as Texans. And Alaskans work far less.

https://www.bls.gov/charts/state-productivity/hours-worked-by-regions-and-states.htm#

Peter

May 29 2024 at 9:29am

Nifty data there, do you know how BLS defines and calculates that? I say that because at least comparing Hawaii (~100) to Texas (~120) it supports Scott’s narrative though California doesn’t but I’m more curious how it’s derived. I’ve lived in both Texas and Hawaii and, and yes it’s just ancedotdal, I didn’t get the impression Texan’s had a significant number of people working multiple jobs nor routinely working 100% overtime or seven days a week whereas in Hawaii it was pretty routine. Curious on how BLS comes up with that.

Anonymous

Jun 3 2024 at 9:36pm

Hawaii is also absolutely chock full of retired rich people, not sure if that is included in the measurement.

Scott Sumner

May 29 2024 at 3:34pm

Weekly hours worked is just one of many factors (and a pretty minor one) in explaining differences in total hours worked. The much lower levels of hours worked in Europe have little to do with the average workweek.

Peter

May 29 2024 at 4:22pm

I’m confused, what hours are we talking about if not work hours when talking about work.

Henri Hein

May 30 2024 at 2:02pm

Lifetime.

Scott Sumner

May 30 2024 at 4:56pm

Hours per year per person. That is also affected by number of weeks of vacation, unemployment rates, people not in the labor force, etc.

Henri Hein

Jun 1 2024 at 1:06pm

My understanding is that high tax rates also change life choices that impact employment. Things like going for a masters instead of a bachelors, retiring early, taking longer family leaves, etc.

Grant Gould

May 30 2024 at 9:49am

AFAICT Massachusetts and Missouri have nearly identical marginal tax rates and similar average tax rates at the same income; Missouri has a lower overall tax rate principally due to its lower per capita income.See https://www.forbes.com/advisor/income-tax-calculator/missouri/ vs https://www.forbes.com/advisor/income-tax-calculator/massachusetts/The “taxachusetts” stereotype from the 1980s not wrong, but MA lowered its taxes at the same time a lot of other states raised theirs so the differences today are more likely to be dominated by municipal property taxes (which apply less obvious income pressure) rather than state income taxes.

JoeF

May 29 2024 at 8:02am

Scott, regarding “standard theory” and the greenhouse effect, you may be interested to read some papers by the great Greek hydrologist, Demetris Koutsoyiannis:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375910182_Revisiting_the_greenhouse_effect-a_hydrological_perspective

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379670369_Relative_Importance_of_Carbon_Dioxide_and_Water_in_the_Greenhouse_Effect_Does_the_Tail_Wag_the_Dog_Preprint

Koutsoyiannis’ papers (and there are many) are always understandable to laymen but they are always also based on mathematical arguments that are open to refutation by professionals. He is something of a model scientist, as he is always open to criticism of his published work and always responds (tirelessly and politely) to questions and criticism (see: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375584665_Causality_Climate_Etc)

Scott Sumner

May 29 2024 at 3:31pm

I find his claims to be highly implausible, as do most scientists. The evidence for the greenhouse effect is pretty overwhelming.

Knut P. Heen

May 30 2024 at 10:47am

The global temperature of the Earth is about 300 Kelvin. The IPCC predicts 3K warming if we double CO2 from 280 ppm to 560 ppm. A further doubling from 560 ppm to 1120 ppm lead to another 3K. The relationship is logarithmic. We are at around 420 ppm now. The point is that 3K is 1 percent of 300K. The skeptics are saying that you have to have a very good model of the Earth’s temperature to claim that a 1 percent change is due to one particular variable (Steve Koonin, for example). You have to rule out changes in all the other variables. This Greek guy is obviously in the camp who thinks changes in other variables (water vapor) also should be studied. He is not disputing the fact that CO2 is a greenhouse gas.

Scott Sumner

May 30 2024 at 4:59pm

OK, but the temperature data in recent decades is strongly supportive of the standard global warming model. So why search for heterodox models.

In addition, talking about a 1% increase on the Kelvin scale is misleading, as you need to think in terms of the normal variation. We’ll never be close to zero degrees Kelvin.

robc

Jun 5 2024 at 5:07pm

Tell that to Buzz Aldrin…but not within punching range.

JoeF

Jun 3 2024 at 8:10am

Well, nowhere in those papers does Koutsoyiannis dispute the greenhouse effect. Rather, he describes how the actual “standard theory” of the greenhouse effect actually mainly concerns water vapor but has been popularized (via computer models, not observation) as being mainly about C02. His analysis of the greenhouse effect is the most parsimonious, which I thought you might appreciate.

Emma

May 29 2024 at 8:46am

Scott,

I’m curious about your take on the different preferences and dynamics between the US and Europe.

For example, looking at the stats here, I see that the gap between hours worked by women vs. men is higher in Europe than in the US. I believe because of longer and and more accessible maternity leave.

Minimum annual leave is also higher in Europe. I don’t know the actual average leave in either the US or Europe but I’d bet it’s still significantly higher on the old continent. I’d bet the workers there are happy about that state of affairs, too. High taxation or not.

I would think the differing health care systems could play a role too.

These are just the first variables off the top of my head that could explain at least a part of the gap between the hours worked.Do you think these are relevant? Are there others? If so, how much of the residual would you attribute to taxation disincentives?Thanks for your input!

PS: I know the welfare policies above are paid for by taxation. But it does not follow european workers necessarily go on vacation because of a tax disincentive.

Scott Sumner

May 29 2024 at 3:44pm

These rules may play a minor role, but even they are partly reflective of tax differences. People are more likely to support mandatory vacation regulations when the hit to after tax income is smaller.

“I’d bet the workers there are happy about that state of affairs, too. High taxation or not.”

It’s hard to say what people think, as they don’t always understand the trade-offs. If asked only about vacations, that sounds good. But suppose you tell them that per capita GDP will be 30% lower? A more interesting question is what do immigrants prefer—more hours and higher income in the US, or fewer hours and lower income in Europe? I suspect that most prefer the US.

Emma

May 30 2024 at 9:11am

Thanks for the answer!It seems to be hard to assess, then, from what I understand. How can one know if people understand the concrete implications of a 15% raise in GDP? Maybe we’d better ask some thing like: would you rather have 4 weeks of annual leave or 8% more salary?Anecdotal, but I know lots of people who would rather have the annual leave instead. Probably a vast majority. And from what I can gather asking GPT, it seems annual leave is generally preferred over salary. Interesting but not really solid. Would be nice to know more about these preferences.Do you think there’s a part here where people in the US feel as though they *have to* work more for like, health insurance reasons?

Scott Sumner

May 30 2024 at 5:02pm

Again, I think the “revealed preference” information in immigration patterns gives us our best read on the issue. Where do people want to move? The US. Where in the US? Places with zero state income tax like Texas and Florida.

Emma

May 30 2024 at 9:20pm

From what I see here, there are more migrants claiming residence in California and New York than in Florida and Texas. Or maybe I’m reading these stats wrong..?

Also, it seems to me that people who have nothing or very little and must (as it is with a lot of them I would guess) send money to the family back home may want to work as much as possible, yes. And with the least amount of taxation, probably. But, don’t you think these preferences may change if and when they have enough to live a somewhat comfortable life? Could they prefer maternal and annual leave over salary, for instance?

Thanks again for the interaction, it’s great!

Knut P. Heen

May 29 2024 at 9:03am

I am convinced that the relationship between taxes and formal hours worked is correct. Higher taxes also mean that it is more expensive to hire a helping hand. Working overtime and hiring someone to install a new kitchen will be taxed twice. You first pay taxes on your extra income, then the kitchen guy have to pay taxes on his income from you. Having more “leisure time” to install the kitchen yourself becomes more valuable when tax rates are high. You are simply not taxed on work you do for yourself and those work hours are not registered as work hours either.

Jose Pablo

May 29 2024 at 12:33pm

It is certainly possible that a welfare state is beneficial despite leading to a reduction in per capita GDP

This sounds like Okun’s leaky bucket.

The problem in this statement (a very serious one) is with the definition of “beneficial”. Beneficial for whom? Measured how?

You need to develop a very complex theory of value (full of normative principles and even more full of assumptions about very different individual preferences) before attempting to falsify such a statement and failing (so that you can still hold it as “true” a little longer).

Grand Rapids Mike

May 29 2024 at 12:38pm

In the US the impact of taxes is shown in not just the hrs worked but also where people just want to live. So consider the migration from NY t0 Florida. Also what is interesting over the impact of differences in taxes and probably the in politics are the Quad Cities area bordering Illinois and Iowa. On Illinois side is Moline and Rock Island and on the Iowa side is Bettendorf and Davenport. Don’t have any metrics to illustrate the specific economic differences, but the Iowa side seems much more prosperous than the Illinois side.

Scott Sumner

May 29 2024 at 3:45pm

Yes, I’ve done many posts here on interstate migration for lower taxes, including the examples you cite.

Jessenia Rodriguez

May 29 2024 at 3:34pm

This is an interesting intake, considering that not everyone pays the same amount in taxes, yet people either work the same 40 hours or more in the states with more taxes. In agreement with Jose Pablo, this benefits who and how is it measured? Depicting the visualization of how higher taxes and the percentage leads to fewer hours worked could persuade those in doubt.

Rajat

May 29 2024 at 5:53pm

On the work disincentives of high taxes, there is clearly some motivated reasoning going on. But most of the policy advocacy material I’ve read – which purports to be based on empirical research – claims that high marginal tax rates don’t much affect the work incentives of higher income people, particularly married men. The idea being that, at the margin, these types of people are driven to work by non-financial motivations such as status. Of course, as you suggest, these studies typically don’t consider very long run effects such as incentives to enter high-value professions or engage in entrepreneurial activities, or the attractiveness of a country to potentially very high-achieving or hard-working migrants.

[That said, I think there is wide acceptance that high effective marginal tax rates (incorporating the withdrawal of means-tested benefits, which are common in Australia) do strongly influence work incentives for groups like low-income earners, students, and second-earners (often, young mothers).]

I agree with Emma that a nation’s culture tends to evolve around its economic incentives. While Europeans may not have made an explicit choice to have 6-week annual holidays and 30% less income than Americans, neither have Americans made their choice. I think many would baulk at the other’s trade-offs. As an Australian, who sits somewhere in between, I would baulk at both choices! European food and wine and ‘villagey’ lifestyle is great, but their homes feel tiny and decrepit. Americans have to work too hard, are too exposed to the vicissitudes of life (and guns!) and I don’t need a bigger house with massive SUVs and jetskis in the garage. The main benefit I would see in being 30% richer would be the types of things you wrote about in your 2011 post responding to Tyler Cowen’s ‘The Great Stagnation’ – a bigger & nicer house, more restaurant meals and more fun vacations. And Americans have these things (although one may question their specific choices), which becomes really obvious when seeing them travelling around places like Europe. Yet even then, American domestic (and international) plane travel is tedious. Given their higher incomes, I would expect American planes to be 30% business class rather than 10%, but that does not seem to be the case. As for what migrants prefer, while high-potential migrants do prefer the US, I wonder how many of the rest would – especially if Europe was willing to loosen its labour laws and run better monetary policy.

Anyway, that is a long-winded way of saying that when culture evolves to economics, it becomes harder to see the independent role that economic incentives play in decision-making.

On ‘money-printing’ and global warming, I think unfortunately these issues got caught up in the culture wars. The most prominent voices warning against actions like QE as inflationary were hair-shirted right-wingers who wanted to ‘liquidate everything’, which was rightly seen as an anti-poor. And most of the international global warning establishment has long-opposed practical options like nuclear power and fracking in favour of renewable subsidies, which was rightly seen as anti-growth.

Scott Sumner

May 30 2024 at 5:07pm

Personally, I prefer the European lifestyle of less money and more leisure time. There might also have been some sorting going on, with America drawing more materialistic people. But the fact that Europeans worked just as long back in 1960 does seem to tell us something about the effect of economic policy—it’s not all culture.

James Quigley

Jun 1 2024 at 12:12pm

Is that preference due to your current financial situation? Meaning you already “made it” and no longer need to work as much/at all?

As someone who is at the cusp of retirement, I agree that more leisure is preferable. My 2 son’s, not so much.

Alex S.

May 29 2024 at 6:02pm

I think the human mind likes to think in terms of intentions and outcomes. Intentions and outcomes are either both good or both bad.

The problem is that most things in the world are probably defined by “bad” intentions (pursuit of self interest) and good outcomes (consumption). Alternatively “good” intentions (socialism), and bad outcomes (unbridled economic collapse and human suffering).

steve

May 29 2024 at 7:38pm

Seems kind of odd that Scott of all people would ignore Asia. Taiwan and China both work longer hours than we do in the US. I have trouble figuring out all of their taxes but it looks like they pay more. Also a number of South American countries appear to both work longer and pay more in taxes. This theory also doesnt seem to hold true very much for individual professions. Certainly medicine, finance and a lot of tech people both pay a lot of taxes and work long hours. I did. Also, if memory serves, Goolsbee wrote a paper on this long ago noting that when taxes were raised executive responded by working longer hours to maintain take home income.

My guess is that it is one of these things that is true but its a minor effect easily outweighed by many other factors in life and culture.

Steve

Scott Sumner

May 30 2024 at 5:12pm

“Taiwan and China both work longer hours than we do in the US. I have trouble figuring out all of their taxes but it looks like they pay more.”

Generally speaking, both taxes and welfare spending are lower in East Asia than in the US. Most Chinese people don’t pay income tax and welfare benefits are meager. But the systems are complex so it’s hard to generalize.

In the US, effective (implicit) marginal tax rates for the poor are often far higher than for doctors and tech people. I’ve done previous posts on these issues.

Thomas L Hutcheson

May 29 2024 at 9:09pm

I guess there coud be some effect, although the fact that both health insurance Social Security are linked to employment rather than being situational transfers finance by a VAT or a personal consumption tax) may be more important that the level of taxation.

Andrew_FL

May 30 2024 at 7:02am

A common thread between the three examples is that the theoretical predictions are qualitative, leaving room for a great deal of quibbling about the actual quantitative effect size.

How much of the difference between European and American hours worked is taxes, how much other factors? That’s hard to prove definitively. How warming does an increment of CO2 cause? Again, hard to prove exactly. In the 2010s it was easy for people to convince themselves the effect of money on prices must be tiny.

You’re probably right that many people engage in motivated reasoning to decide which effect sizes they think are plausibly negligible, although that in and of itself doesn’t mean they are wrong. And I could argue that some are more plausibly right than others…but I won’t get into that here.

Jon Murphy

May 30 2024 at 1:07pm

You will find that is true of all sciences. Everyone who learns statistics learns about error bars, confidence levels, probability, etc. You will never, ever, be able to prove anything definitively.

Theory helps us make predictions. It helps us sort the wheat from the chaffe.

Vivian Darkbloom

May 30 2024 at 2:52pm

“How much of the difference between European and American hours worked is taxes, how much other factors? ”

Good question. Prescott admits as much in his paper, but then goes on to ignore other factors and attribute the difference in hours worked to “marginal tax rates”:

“I emphasize that my labor supply measure is hours worked per person 15-64 in the taxed market sector. The two principal margins of work effort are hours actually worked by employees and the fraction of the working age population that work. Paid vacations, sick leave, and holidays are hours of non working time. The time of someone working in the underground economy or in the home sector is not counted. Other things equal, a country with more weeks of vacations and more holidays will have a lower labor supply in the sense that I am using the term. I focus only on that part of working time that the resulting labor income is taxed.”

Prescott makes no attempt to quantify the effect of those other factors. Had he done so, I think he would have found that those other factors account for quite a bit of the difference. That’s disappointing for a Nobel laureate. For example:

Paid vacations are, as mandated by law, significantly more generous in, say, France and Germany than the US (five weeks paid during the latter part of the 1990’s). This isn’t taxes coming back in the form of transfers. It’s a burden placed on employers.

Public holidays are also significantly higher (see for yourself: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_number_of_public_holidays);

In my experience, the underground economy in France, where I live, is huge. Try getting a repair person to work on the books—it’s the exception, not the rule. Also, a very large percentage of houses built here are built by the owner (France is a country of “bricoleurs”). Indirectly, this is the result of higher taxes; however, they do ignore the amount of “hours worked” by excluding them in the official statistics;

Unemployment benefits are typically longer with a greater percent of the working population collecting them (the trick here is to work for a few months, collect unemployment for a year, then rinse and repeat). To some extent this entails taxes coming back as benefits; however, the relevant factor is not *marginal* but *average* taxes that enables those benefits to be paid;

I could list quite a number of other factors that possibly explain the difference in hours worked (culture, to mention just one). While I can somewhat buy the theory about marginal tax rates reducing the supply of labor, many people seem reluctant to accept that other factors probably play a greater role in explaining the dfference in the number of hours worked between Europeans and Americans. And, it’s funny that I recall reading here recently someone bemoaning the tendency of folks to attribute causes to just one factor, rather than many….

Scott Sumner

May 30 2024 at 5:18pm

I don’t find any of those arguments to be persuasive. Rules on paid leave reflect the preferences of the public, which reflect taxes. A large underground economy is a prediction of supply side models. Unemployment benefits are part of what Prescott means by an implicit tax rate.

Vivian Darkbloom

May 31 2024 at 3:26pm

Those are not arguments, they are facts— “reality!”.

And, you are confusing cause and effect. If higher European taxes reflect preferences of the European public (as *you* assert),higher taxes are the effect, not the cause of shorter work hours. The cause is basically “culture”. Essentially, Europeans do prefer more leisure and are more willing to indirectly pay for that leisure. In this regard, the relative dis-incentive to work is the result of the preference for leisure, not higher marginal tax rates. If the disincentive were higher marginal tax rates on labor, the cause would be “I don’t want to work more hours because I won’t be able to pocket much of my gross pay”. No, the cause is I don’t want to work more hours because I prefer more leisure.

And, again, higher mandatory paid vacations and public holidays are not financed through taxes—employers bear the brunt of that through higher labor costs. To the extent that higher taxes indirectly pay for that leisure, they are paid for by average, not marginal taxes (including, notably, European value added consumption taxes).

Roger McKinney

Jun 1 2024 at 12:33pm

They seem to ignore state taxes in the US, too. Added to federal, total taxation in the US us closer to 40%, not greatly different from Europe.

Roger McKinney

May 31 2024 at 12:23pm

Time series analysis of the data shows CO2 levels lagging warming, indicating CO2 levels are an effect of warming not a cause. The climate models have a margin of error of about 25 degrees.

Good climate science is in the minority opinion, just like good economics. And like economics, climate science among the majority is contaminated with the desire to use it to advance socialism.

David Henderson

Jun 1 2024 at 5:28pm

Good point.

Also, even aside from that, we don’t typically say that because our theory says changes in x should cause changes in y, let’s look only at x and not at other potential causal factors.

So, for example, I say that an increase in the minimum wage should cause a reduction in jobs for low-skilled people. But I wouldn’t want to attribute all of the reduction in jobs to the increase in the minimum wage without looking at other plausible factors.

Yet that seems to be what many global warming believers do: attribute virtually all the increase in temperature to increases in CO2.

James Quigley

Jun 1 2024 at 12:13pm

Did I really write “son’s?”

Thomas L Hutcheson

Jun 2 2024 at 5:47pm

What is the significance of “accepting” this fact and theory? That it is better to tax consumption than income? Sign me up!

Thomas L Hutcheson

Jun 2 2024 at 5:52pm

What would Jenner think about anti-vaxxers? Ricardo of Republicans and Left wing democrats?Economists’ work is never done.

Pemakin

Jun 5 2024 at 3:43pm

I would hope that Hume would note that showing that data on a log scale would be more appropriate.

Comments are closed.