Chicago Booth’s “Initiative on Global Markets” (IGM) occasionally publishes the responses of fairly well-known economists at prestigious schools on various public policy issues.

On June 7, IGM published responses on the topic of price gouging. It asked 2 questions. I’ll discuss the first and the answers to the first.

Question A: It would serve the US economy well to make it unlawful for companies with revenues over $1 billion to offer goods or services for sale at an “unconscionably excessive price” during an exceptional market shock.

What would my A and A- students have answered at the end of a course while the material was fresh? I think they would have said “No” or “Hell, no.”

The options given were “Strongly Agree” (Hell, yes), “Agree” (Yes), “Uncertain,” “Disagree” (No), “Strong Disagree (Hell, no), “No Opinion,” or “Did Not Answer.”

First the good news.

44% of respondents disagreed and 21% strongly disagreed. No one strongly agreed and only 5% agreed.

Wait; there’s more good news. Weighted by each respondent’s confident, the results are even more lopsided. Only 3% agreed, 52% disagreed, and 32% strongly disagreed.

Now the bad news prefaced with a little good news from Eric Maskin and Austan Goolsbee.

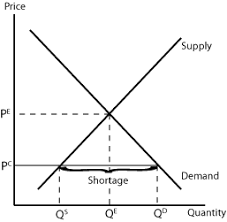

Respondents were also allowed to give reasons. What would be a good reason? How about this: price controls cause shortages and it’s precisely when there are “exceptional market shocks” that it’s even more crucial to avoid price controls. Think of price controls on ice during an electricity blackout or on plywood during a hurricane.

Many of them did not bother giving reasons. That’s understandable. These people are busy and they might well think that the reasons I think are obvious are indeed obvious.

Eric Maskin of Harvard said it well:

At a time of shortage, high prices can serve to stimulate an increase in supply.

Actually, it’s quantity supplied (think of a movement along a supply curve), but again, I’m sure he was in a hurry.

Austan Goolsbee of the University of Chicago has a good answer that expresses his frustration at the question being raised:

How are we back on this again?

This is in line with his earlier comment on a similar question.

Caroline Hoxby of Stanford starts strong but then ends with a surprising concession:

Prices re-equilibrate markets by generating supply & demand responses. Suppressing prices is counterproductive except in short-term events like hurricanes.

No! Hurricanes are not an exception. It’s even more important to get supply and demand responses during a hurricane. If the hurricane is in Florida, it’s good to have trucks lining up in Georgia and South Caroline to ship plywood in for high prices. And it’s good to cause the wealthy mansion owner to question whether he can make do with plywood to fill in his picture windows but without plywood to fix his tool shed. If he foregoes the latter, that frees up plywood for the guy with the double-wide trailer.

Some economists responded like lawyers instead of economists. Oliver Hart of Harvard, for example, wrote:

The terms “unconsciously excessive price” and “exceptional market shock” are not well-defined and so enforcement would be a nightmare.

All true, but even if enforcement were not a nightmare, the shortages caused would be.

Similarly, Ken Judd of Stanford responded:

What is the definition of “unconscionable”? Laws must be far clearer and more precise than vague phrases that express moral sentiments.

Good point, but what if the laws were totally clear: for example, you may not raise prices by more than 50% of what they averaged in the previous 3 months? Would Ken be happy with that kind of law?

Carl Shapiro of UC Berkeley writes:

The first step is to define an “unconscionably excessive price.” Once that is done, economists can evaluate the effects of this bill.

Sure. But why would his evaluation depend on the definition? If the price control is binding, there will be a shortage.

So good on them for their brief answers but not so good on many of the explanations.

READER COMMENTS

Max

Jun 10 2022 at 9:44pm

Austan’s reply seemed best. It is strange to see topics covered in Economics 101 and long since settled being brought up for relitigation time and time again. This feels like the equivalent of asking physicists if they expect a rock and a feather to hit the ground at the same time when dropped in a vacuum sealed chamber.

Jose Pablo

Jun 12 2022 at 2:32pm

“It is strange to see topics covered in Economics 101 and long since settled being brought up for relitigation time and time again.”

It is the opposite of “strange” since it is happening on a daily basis. See, trade deficits, international commerce, competitive advantage, minimum wages, “narrow base” tax systems, corporate tax, excess regulation .. you name it!

John hare

Jun 11 2022 at 12:56pm

Hmmm gas at $5.00 a gallon or can’t get to work and have no income. Decisions decisions.

Jon Murphy

Jun 11 2022 at 4:43pm

With gas controls, the choice becomes “No gas and can’t get to work or get real lucky with gas and can’t get to work.”

Jose Pablo

Jun 12 2022 at 2:40pm

If your “gross” income per trip is less than the cost of gas per trip, you have no net income regardless of what “decission” you make.

If the value of your work is less than the cost of gas, allocating gas to you by decree is wasteful. Somebody doing more valuable things will be let with no gas by the allocating decisions of the “Commitee for Fair&Inclusive Gas Allocation to Disfavoured Workers”

Anders Jönsson

Jun 11 2022 at 7:53pm

What i do not get it… how does this narrative pass even the sniff test. I never studied economics, but hasnt the us increased money supply by a factor of… something like 8? While ourput increased by, what, 1.5. So to an amateur the only way that could not lead to inflation must be exceptionally low velocity of money. Apparently, covid stimulus unbuttoned that cork.

please bear with my naivite here, I know I am missing something big. But my question in quora only incurred ridicule and references to Nobel prize winner opeds, which also never explained how inflation could have been contained and what kind of market power is able to gouge on such a scale? He was a brilliant economist, so I know it cannot have anything to do with silly conspiracy theories.

Your arguments here are convincing by dint of sounding like common sense. But if is common sense, you do not need to make it. I like economics from the little I have read, but here I feel hoodwinked by both sides. Would someone please have the courage to break our of the echo chamber and tell me what im missing?

Jon Murphy

Jun 12 2022 at 7:55am

I am not a monetary economist, so take this with a grain of salt, but I believe the rationale is they flooded the market with money to prevent a financial crisis and expected the Fed to roll things back faster than they have.

Jon Murphy

Jun 12 2022 at 7:23am

I wonder if she is thinking of the welfare effects of price controls with perfectly inelastic supply. In that case, there is no “official” deadweight loss from the price controls. But you are right, there are still shortages from the price controls even if it doesn’t show up in the surplus analysis.

Jon Murphy

Jun 12 2022 at 7:52am

It’s interesting that the only one who gave an answer for their “agree” vote (Darrel Duffie, Stanford) gave a non-economic answer:

Comments are closed.