“Fiscal dominance” refers to the state’s expenditures (fiscal policy) dominating monetary policy. Instead of the legislature (Congress in the US) controlling government expenditures while the central bank (the Fed) tries to control inflation, the latter helps finance expenditures and Congress obtains more leeway to run deficits. Fiscal dominance is the opposite of central bank independence. The idea is making a comeback (see Ian Smith, “Investors Warn of ‘New Era of Fiscal Dominance’ in Global Markets,” Financial Times, August 20, 2025; see also Greg Ip, “Get Ready for the End of Fed Independence,” Wall Street Journal, August 26, 2025).

From a monetarist viewpoint, fiscal dominance would lead the Fed, under political pressure, to increase the money supply to stimulate the economy, if not to finance the government more directly. Other macroeconomic theories emphasize different means of intervention and different causality chains. For example, the central bank may try to push down interest rates in order to reduce the government’s interest costs on its deficits and on the rolling of its debt.

As investors start to fear inflation, however, long-term interest rates, including on mortgages, will increase because a higher risk premium is required to incentivize the lenders. This probably explains the recent increase in the spread between long-term and short-term interest rates. (Co-blogger Jon Murphy made important related points earlier this week.)

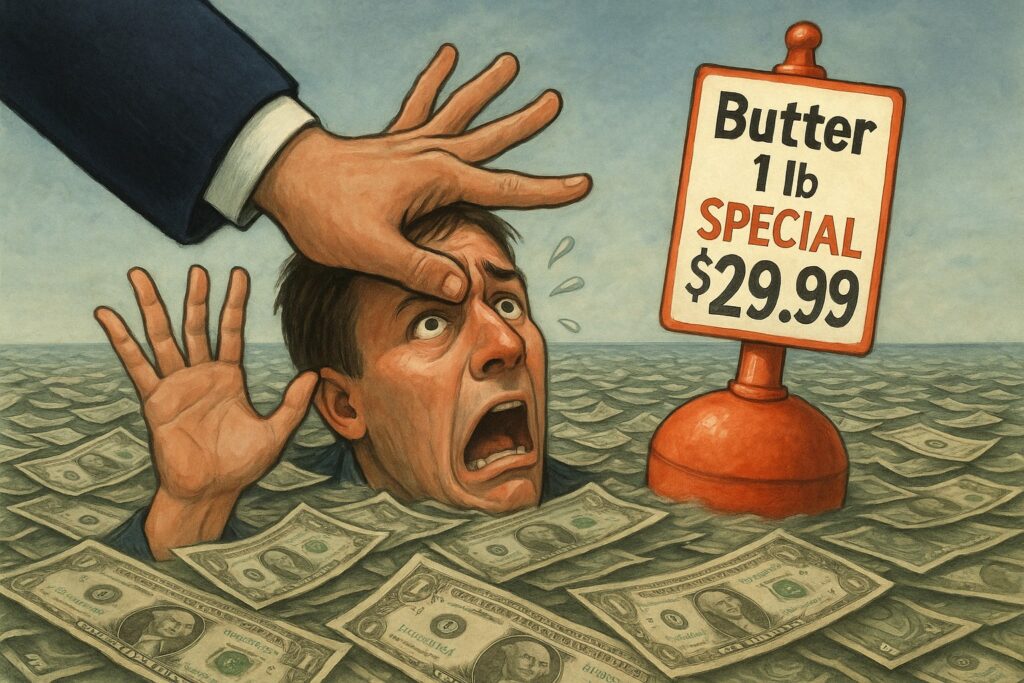

One way or another, sooner or later, fiscal dominance will lead to inflation, which is defined as a sustained increase in the price level. It is sustained in the sense that the central bank sustains it or “accommodates” it. Under fiscal dominance, the central bank cannot resist pressure from the ruling politicians. Many government expenditures, such as Social Security, are indexed to inflation, but some unprotected political clienteles will cry for assistance. Worsening budget deficits and further financing assistance from an obedient central bank can thus generate a self-perpetuating vicious circle.

“Financial repression” is the use of financial and regulatory means by the government to divert resources away from the private economy to itself. Inflation is a major instrument of financial repression. It played a large part in financing WWII as well as the growth of the welfare state in the 1970s. The political pressures for fiscal dominance suggest that financial repression through inflation will return.

In this context, inflation is the result of the government bidding up prices and winning the bidding to get the resources to produce and do what it wants. The government can always win (in the virtual auctions that markets are) if the obedient central bank finances whatever its master needs to be among the highest bidders. Note that the government largely bids against its own citizens.

Populist governments have been habitual practitioners of financial repression through inflation. In their study on the economics of populist regimes over more than a century, many of them South American and European, Cas Mudde (University of Georgia and University of Oslo) and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser (Diego Portales University in Santiago de Chile) provide some econometric evidence to that effect (“Populist Leaders and the Economy,” American Economic Review, vol. 113, no. 12 [2023]). Inflation produces a stealth increase in real taxation (gaining control over real resources), which allows the government to bribe the clienteles whose support is most needed. Think of Nicolás Maduro or Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The latter also believed that pushing down interest rates would reduce inflation, with the consequence that the annual increase in the country’s consumer price index reached 80% and is still half that rate (“Turkey’s Economic Woes Catch Up With Erdoğan,” Financial Times, June 27, 2025).

After the speech of the Fed’s chairman in Jackson Hole, an editorial in the Wall Street Journal notes (“Powell Flips the Fed’s ‘Framework,’” August 22, 2025):

The Fed Chair on Friday seemed to move toward the view that tariffs won’t lead to permanently higher inflation. “A reasonable base case is that the effects will be relatively short lived—a one-time shift in the price level,” Mr. Powell said.

The editorialists could have been a bit more explicit on this point. A supply shock caused by a large increase in tariffs shifts the production possibility frontier downward and thus generates a one-time increase in the general price level. It may not cause inflation in the sense of a sustained increase in the price level, but only if the Fed doesn’t sustain it by increasing the money supply or helping finance the government deficit in some way (see my “Assessing Trump’s New Tariff Ideas,” Regulation, vol. 47, no. 3 [Fall 2024]).

These rather basic observations do not imply that a more radical criticism of central banking is not warranted (see my post “A Bad Solution to Very Real Problems,” January 31, 2018). On the contrary, the Fed participates in the logic of self-sustaining government intervention. Government intervention begets government intervention. At a time when nationalization appears (again!) as the solution to all problems, radical critiques need to be emphasized.

******************************

Financial repression, by ChatGPT

READER COMMENTS

Craig

Aug 28 2025 at 12:51pm

“fiscal dominance will lead to inflation” <–many ways out of the current fiscal debacle, but ultimately I feel the regime will, like many regimes before it, resort to inflation. The checks MUST go out. Soon we will see if the theory is correct that reverse repo dropping close to 0 might result in a yield spike and a ‘failed’ auction where the Fed intervenes to buy the bonds.

Matthias

Aug 29 2025 at 11:01am

You are mixing up a lot of things.

(1) Central bank doesn’t have to mean central planning: eg Scott Sumner suggests we should use (prediction) market prices to guide policy.

(2) Central banking, even with central planning, doesn’t mean interest rates need to be an instrument (nor target) of monetary policy. The Monetary Authority of Singapore shows that you can do effective monetary policy and still leave interest rates completely to the markets.

Messing with interest rates might be bad, and central banking might be bad. But they are far from the same thing.

Matthias

Aug 29 2025 at 11:01am

Sorry, the above should have gone to Pablo’s comment.

Pierre Lemieux

Aug 28 2025 at 3:43pm

Craig: We’ll certainly learn a lot in the next few months or years, at a high cost I fear.

Jose Pablo

Aug 28 2025 at 8:38pm

One of the few blessings of Trump’s regime is that it has laid bare just how naive the notion of an “independent” monetary policy always was.

So long as governments exist, and the ego or personal interests of presidents are at stake, monetary policy cannot, and will not, be “independent” (independent of what, exactly?). The whole idea is nothing more than a pipe dream.

And, as you point out in your post, the belief that a group of supposedly all-knowing experts can fine-tune the “right” amount of money in the system to maximize “economic well-being” (whatever that means) is no less naive.

I see no real difference between the damage caused by the so-called “technical” mistakes of experts, whose historical record of error is appalling, and the damage caused by politically driven interventions. At times, their mistakes may even cancel each other out.

The fatal conceit, in any case, is the collective illusion that interest rates are best set by some imagined “central intelligence,” whether political or technical. The problem with the Gosplan was not that its members weren’t highly regarded experts, or that they lacked independence from political power.

Craig

Aug 28 2025 at 9:37pm

“The fatal conceit, in any case, is the collective illusion that interest rates are best set by some imagined “central intelligence,” whether political or technical. ” — QFT JP

Matthias

Aug 29 2025 at 11:03am

You are mixing up a lot of things.

(1) Central bank doesn’t have to mean central planning: eg Scott Sumner suggests we should use (prediction) market prices to guide policy.

(2) Central banking, even with central planning, doesn’t mean interest rates need to be an instrument (nor target) of monetary policy. The Monetary Authority of Singapore shows that you can do effective monetary policy and still leave interest rates completely to the markets.

Messing with interest rates might be bad, and central banking might be bad. But they are far from the same thing.

You also seem to be drawing universal lessons from an American phenomenon. Much of the rest of the world has independent central banking, no matter what shenanigans are happening in American politics.

Jose Pablo

Sep 1 2025 at 12:57pm

The Fed’s independence is, at bottom, a political choice. The government decided on it because, at the time, it believed that was the best policy for America’s prosperity. It doesn’t even have the rank of a constitutional provision—it rests on nothing more than “ordinary legislation,” a statutory law.

Which means the government can just as easily decide it no longer thinks that policy is best, and change it.

It’s far from clear that having an independent Fed is the optimal political arrangement (just as it’s far from clear that giving the Fed a dual mandate makes sense, most likely, it doesn’t). In fact, the “best” political decision is, by definition, whatever the relevant branch of government at any given moment decides it is.

And in this case, as in many others, we really don’t know what the best monetary policy is. We don’t even have a universally validated economic theory that reliably explains the link between interest rates and inflation, only competing models and rules of thumb. (On this, see Cochrane’s very interesting discussion in the Wall Street Journal here).

The broader question, whether government can ever effectively bind itself, always comes up, and the answer is always a resounding no. It can’t, and it won’t. It’s always and everywhere just a matter of time before those “restraints” break down.

The only answer, then, is to make the realm of collective decisions as small as possible, ideally nonexistent. Because the strategy of expanding that realm and trying to handcuff the government within it is doomed from the start. No exceptions.

In monetary matters, that means I want (like Cochrane) a currency that holds its value (a 0% inflation target), that doesn’t concern itself with employment, and over which government has virtually no say. I want a system where a private actor can issue such a currency simply because some of us want it. And if the government prefers, it can issue its own currency, run by a central bank staffed with Martians, for all I care.

Let the best currency win. Experts are fine, but I trust them only a little more than politicians, and that’s a very low bar.

Jose Pablo

Sep 1 2025 at 1:18pm

This issue has corollaries that are more thought-provoking than the question of central bank independence itself.

Government deficits could, in principle, be determined at the individual level. The mechanics of such an arrangement would be straightforward, which makes it puzzling that it has not been explored more seriously.

Taxation could likewise be structured as voluntary contributions at the individual level. While this would admittedly create a free-rider problem, it would not necessarily be larger, merely different, from the free-rider problem that an arbitrary tax code creates relative to its possible alternatives.

Tariffs, too, could be approached in this way. Individuals who wish to support domestic industries or penalize foreign producers could voluntarily remit to the government a payment of their choosing, corresponding to purchases they classify as subject to tariffs.

Mactoul

Aug 29 2025 at 12:20am

The analysis, fine as it is, is marked by conspicuous absence of methodological individualism. Abstractions and collectives such as government and Fed do things, prefer things and so on.

Pierre Lemieux

Aug 29 2025 at 9:49am

Mactoul: With due respect, I don’t think you understand methodological analysis. Your objection is well-known, and the best way to go through it to understand Hayek’s distinction between society (a spontaneous order) and an organization (see vol. 1 of his Law, Legislation, and Liberty). An organization is formed by two or more individuals who want to pursue a common goal (maximize profits or encourage bird watching) while society is the locus where each individual (or organization) pursues his own goals (even if some dictator tries to forbid them to do so).

Mactoul

Aug 29 2025 at 11:14pm

I am confused. Only in the last post, it was maintained that a legislature couldn’t have an intent because of methodological individualism.

Now you say that government is an organization that does possess goals (and presumably intents).

My other question remains– what is the purpose or role of government in classical liberalism. And does American Constitution satisfy the classical liberalism requirements?

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 1 2025 at 5:45pm

Matoul: On your first paragraph, I never maintained that a group of people in a committee within an organization could not vote and produce a result (which will not necessarily be logically coherent–see the paradox of Condorcet.

About your last paragraph, this is what I and many people on this blog are trying to discover. You are most welcome to join our inquiry.

Monte

Aug 30 2025 at 2:05am

The Fed today has the independence of an artificial limb and operates with a superfluity of purpose. It was created to do for the government what markets won’t, which is intervene on behalf of politicians for political expediency.

We need more Fed chairmen like Volker, who’s willingness to make unpopular decisions in the face of both political and public pressure definitely set him apart in terms of independence.

#abolishthefed

Jose Pablo

Sep 1 2025 at 8:43pm

#abolishthefed

or at the very least, let it compete with private currencies, governed by whatever rules private innovators devise.

That competition, not the applause or criticism of other so-called experts, or our opinion on the level of its independence, is the true test of the Federal Reserve system’s value.

Monte

Sep 1 2025 at 10:28pm

The idea has merit and has been suggested in the past:

On top of that, at least repeal the Federal Reserve Act.

Comments are closed.