Jane Shaw Stroup wrote a short and rather effective piece on Hayek’s “atavism thesis”. Hayek came to it, as she writes, after a life of struggling with socialism and economic interventionism.

F.A. Hayek was born in 1899, he fought in WWI (contracting the Spanish flu and malaria on his way back from the trenches), and was exposed, as a young man, to the most unpropitious series of events – which did not make liberalism very popular among men and women of his generation. On the contrary, liberalism was on the wane. 19th century liberalism had many nuances but all shared the urge to move from discretionary rule to something which resembled automatic mechanisms, reducing politics at best to a very limited, technical endeavour. Of course some politicians tended to be larger than life, flamboyant personalities who could mastermind public opinion in the 19th century too. But liberals, of all sorts, were skeptical of their playing public opinion as a piano in order to be legitimised in taking decisions of their own liking. Public opinion ought to be a tribunal, severely scrutinising all collective action and possibly keeping precisely those types in check.

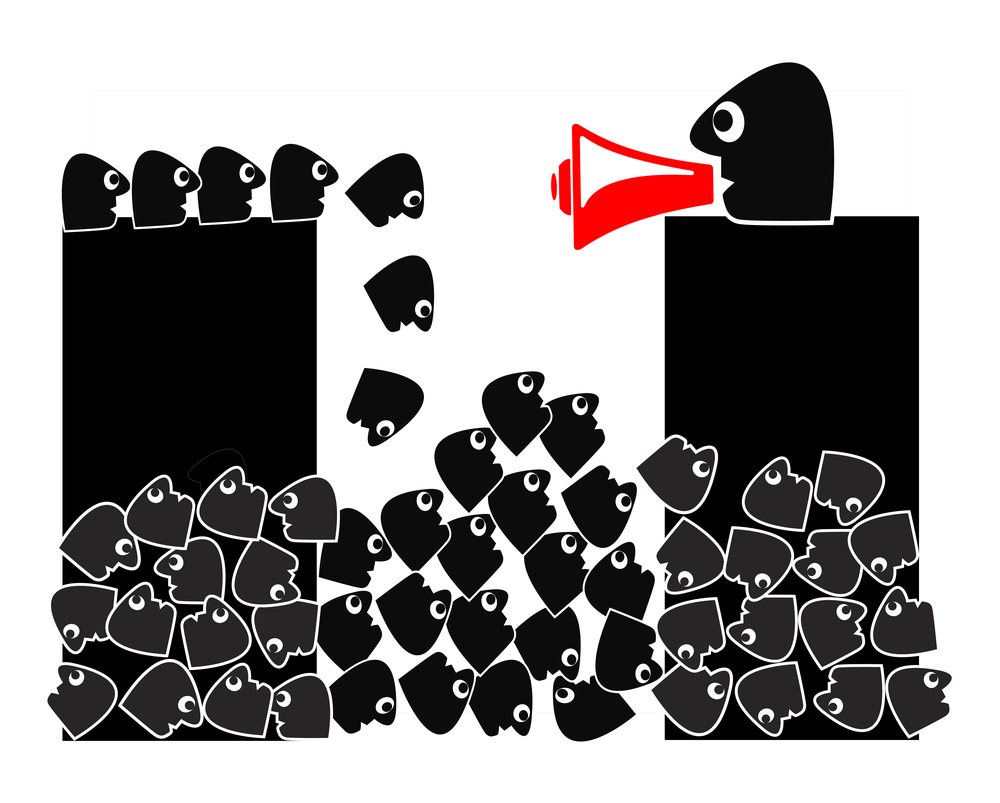

The 20th century was the triumph of boldness: bold leaders, bold decisions, bold ambitions. Politics, quite far from being a limited endeavour, was to reshape the very nature of man.

The few savvy people around asked themselves how it was possible that the most educated societies which ever existed could fall for that. Many thought it was a problem of education. The truths of political economy were, for example, by and large counterintuitive and hence difficult to digest. Hayek followed that path too, hence his insistence in better educating “second hand dealers in ideas” (journalists, high school teachers, etc) who tended to spread bad ideas in good faith. But at a certain point, after many a year of struggling within those ideas while treating in the kindest, more gentlemanly and scholarly manner those holding them, Hayek realised that perhaps the problem lies not in education but before education.

Hayek concluded that humans have instincts that evolved genetically, starting with humans’ predecessors, animals in a pack, and continuing when humans lived together in small bands. This evolution ended only about 12,000 years ago.

Those instincts weren’t inherently bad. In fact, they included essential emotions, such as solidarity and compassion, that kept the band alive. But they were beneficial only when people lived in small groups. The growth of what Hayek called the “extended order”—trade and communication outside the band, the modern economy—required people to act differently.

“Mankind achieved civilization by developing and learning to follow rules (first in territorial tribes and then over broader reaches) that often forbade him to do what his instincts demanded, and no longer depended on a common perception of events.”[5]

Humans have never entirely given up their early instincts, however, and that draws them to socialism and fascism, said Hayek. Socialism and fascism give them the “visible common purpose”[6] so essential in the distant past. But forcing people to share a visible common purpose is not compatible with freedom.

Contemporary research on cognitive biases tends to reinforce Hayek’s point. I’d like to add, to Jane Shaw’s splendid little essay, only one caveat. These innate instincts are not something of concern only when we deal with the masses or with ordinary people – as many educated people tend to believe. They are deeply ingrained with all of us, and make even the most educated and sophisticated experience lust for super-imposed “order” or enjoying the vertigo of feeling part of the team of the good and right.

READER COMMENTS

Paul Sand

Aug 6 2022 at 7:46am

I recently read (well: looked at every page of) the late Gerald Gaus’s book The Open Society and Its Complexities. He provided (I think) a somewhat more optimistic view than Hayek’s, based on subsequent decades of anthropological/sociological research. I’m not qualified to judge one way or the other, but folks interested in the matter should check Gaus out. Here’s a short and non-academic essay from him: “The Open Society and Its Friends“.

Alberto Mingardi

Aug 7 2022 at 8:22am

Thank you. A splendid essay.

nobody.really

Aug 9 2022 at 12:32pm

Friedrich A. Hayek, Law, Legislation and Liberty, Vol. 3 (1979), “Epilogue: The Three Sources of Human Values,” at 528-29 (emphasis in original).

What lessons does this have for democracy/libertarianism?

Comments are closed.