Hyperinflation in Germany, 1921-1923

The Weimar Republic, born at the end of World War One in November 1918, inherited debt and political instability.

Germany borrowed heavily to finance the war planning, like the other combatants, to make the losers pay. In 1915, Treasury Secretary Karl Helfferich told the Reichstag: “It is the [Allies] who deserve to bear this lead weight of billions. Let them drag it through the decades to come, not us.” Defeat meant that, not only was that impossible, but the Allies were likely to make Germany pay.

In addition, revolution simmered below the surface, occasionally boiling over as in the leftist Spartacist uprising in January 1919, the rightist Kapp Putsch of March 1920, and numerous assassinations of high profile political figures.

The government spent money to buy social peace. When railway workers struck for higher wages in May 1919, Prussia’s Finance Minister said, “Every price and every kind of concession is justified to prevent the shutdown of railroad traffic in Prussia.” Initially, Germans were willing to lend to their government to finance this: Until late 1921, the proportion of treasury bills held outside the Reichsbank never fell below 50%.

But in May 1921 the Allies finally presented Germany with the bill: 132 billion in gold – inflation proof – marks. The terms were not as onerous as they appeared, but one billion in approved foreign currency or Treasury bills was due by September. The government complied, but only via such expedients as shipping out 560 cases of Reichsbank gold, borrowing a quarter of a billion, and dumping paper marks on foreign exchange markets.

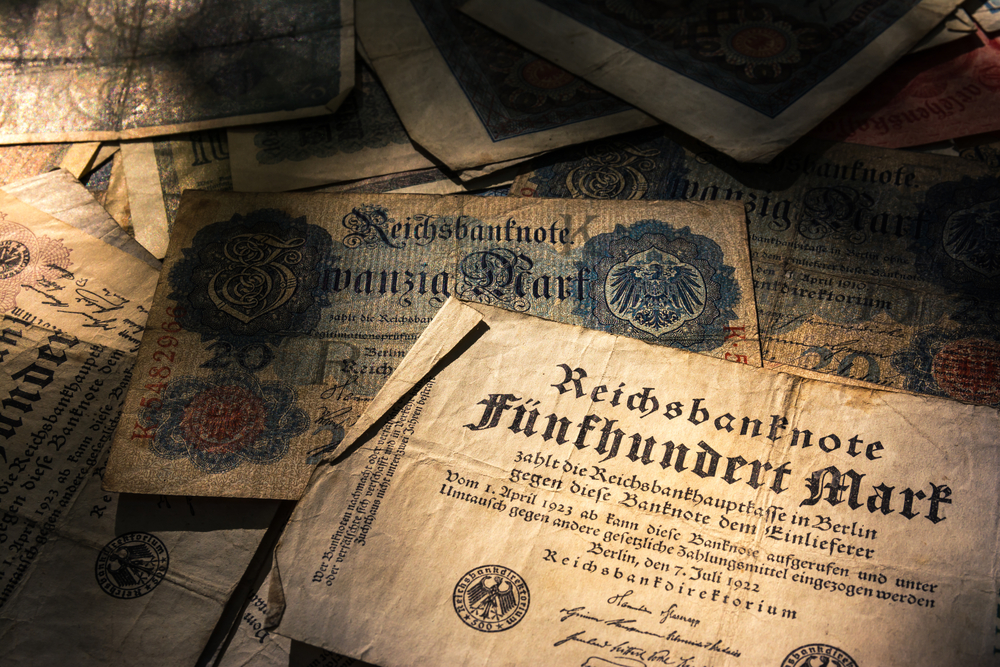

Unwilling to finance the payment of reparations almost universally regarded as unjust, Germans stopped lending to their government. The Reichsbank stepped in as lender of last resort, buying government debt with newly printed money. Between December 1921 and July 1922, the amount of domestic bills and cheques held by the Reichsbank rose by 616%, from 922 million marks to 6.6 billion. In May, just 21% of the government’s income came from taxes, the rest from selling Treasury bills to the Reichsbank in return for newly printed marks.

July 1922 saw prices rise 50%, the generally accepted definition of hyperinflation, and the cost of living rose a further 71% between August and September. “The unprecedented fall of the mark in the last few days differs from the previous falls,” the Guardian reported, “This time it is a general psychological panic wave…”

As the mark’s rate of depreciation accelerated, people looked to swap them for other things – anything – as quickly as possible before they lost their purchasing power. This could take comical forms: In early 1923, the Guardian reported:

In January 1923, in response to non-payment of reparations, France and Belgium occupied Germany’s industrial heartland, the Ruhr. This was a grave economic blow, compounded by the Berlin government covering the wages of workers idled in a campaign of non-cooperation with the occupation. An attempt to borrow $200 million to finance this failed and the Treasury increasingly turned to the central bank. Apart from the State Printing Office, 130 other printers were producing marks. Sometimes only one side was printed to save time and cost.

This new money no longer bought social peace. By late 1923, Germany’s real income was barely half that of 1913. Unemployment among the unionised workforce rose from 4% in July 1923 to 23% in October. Bread riots broke out. Leftist uprisings in Saxony and Thuringia were crushed but there were rumbles from a new rightist group, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, in Bavaria.

A new government under Gustav Stresemann – the eighth Chancellor in five years – took office in August armed with dictatorial powers. It announced plans to improve tax collections and cut spending by dismissing a quarter of its employees over four years. It also introduced a new currency. “With the introduction of the Rentenmark the process of borrowing by way of discounted Treasury bills and thereby increasing the note circulation is to cease,” the Times reported, “It is obvious that unless the budget is balanced by combining economy with taxation the Rentenmark is foredoomed to the same fate as the paper mark.”

The Rentenmark went into circulation on November 15 and the hyperinflation ended surprisingly rapidly. The government was helped by a resolution of the reparations issue with the Dawes Plan in 1924, which reduced annual payments though not the overall amount. Foreign capital poured into Germany and the economy recovered. All would be well if this flow of capital continued. It would not…

John Phelan is an Economist at Center of the American Experiment.