It was just reported that South Korea’s birth rate fell to a record low:

Korean women were estimated, based on 2021 data, to have an average of just 0.81 children over their lifetimes, down from 0.84 a year earlier, the statistics office said Wednesday.

A graph in the Bloomberg article provides some context:

People need to stop talking about Japan’s birth rate and start talking about Korea.

The world’s highest fertility rate is in Niger, at 6.7 children per woman. Of course, South Korea and Niger differ in all sorts of ways. But it’s worth noting that South Korea’s lifetime fertility rate was roughly 5 per woman back in the 1950s, a time when Korea was as poor as sub-Saharan Africa.

If you talk to people in Korea, they’ll say that the birth rate is low because Koreans cannot afford large families. That’s a bit odd given that (since 1960) South Korea has become richer at a faster rate than any other country on Earth. How could Koreans in the 1950s afford large families? How can residents of Niger afford large families? Yes, you can amend the argument to reflect rising expectations of the Korean middle class, but it still seems somehow inadequate. It’s too easy an answer—for instance it doesn’t explain the huge gap with equally rich Japan.

There’s another area where Korea is a world leader—putting pressure on students to do well in school in order to get accepted at good universities (and ultimately to get good jobs.) Perhaps that competitive drive is pushing down birth rates, as Korean families try to maximize the average success of their children, not the total success.

I sometimes wonder if highly competitive cultures are engaged in a sort of zero sum game arms race, trying to do better on arbitrary academic tests in order to get one step ahead of their neighbor. That seems wasteful.

And yet, I just said South Korea has the world’s fastest growing economy since 1960, so it’s not obvious that a relentless drive to succeed is a bad thing. But perhaps even a good thing can be pushed too far. How important is lots of extra hours of studying, at the margin?

People often like to compare the educational regimes of Sweden and Finland. By conventional measures such as test scores, Finland’s approach is more successful than Sweden’s. The Swedes seem to focus more on making students happy.

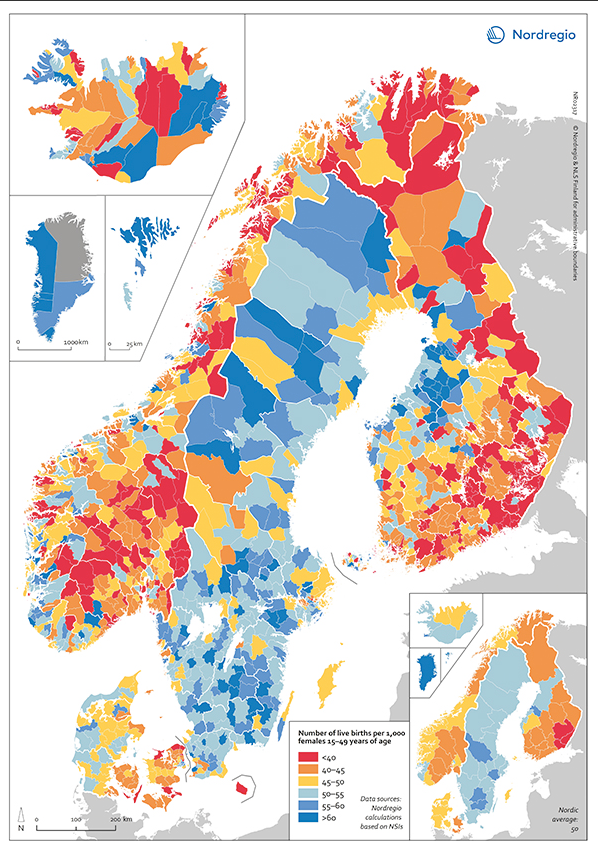

But there’s more to life than test scores. For instance, Sweden is richer than Finland, despite its less competitive education system. It’s also worth noting that Sweden has a higher birthrate. Notice that blue tinted Sweden is an island of fertility between the reddish-orange of Finland and Norway:

(In fairness, the gap between the Swedish and Finnish educational systems has narrowed in recent years.)

I am agnostic on the optimal fertility rate, and I’m also agnostic on the question of what makes people happy. Is having students study hard a good thing? Is more fertility a good thing? Does more GDP per capita make us happier (once we are a developed country)? I don’t see the answers to any of these questions as being obvious. And yet I see other pundits talk about what’s best with a high degree of confidence.

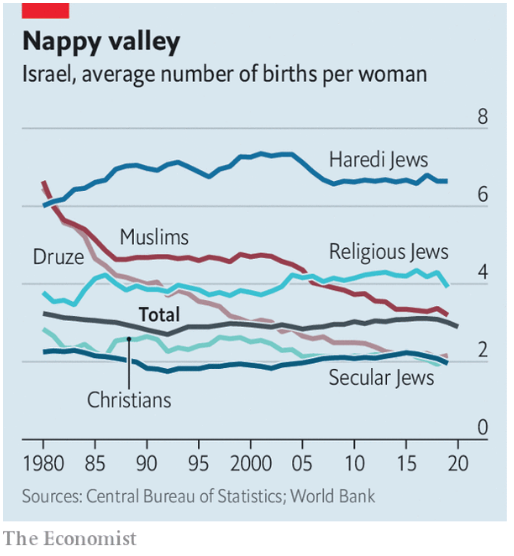

PS. Israel is a case worth thinking about. Secular Jews have about 2 children per woman, whereas the most highly religious groups have about 6.6 children per woman, comparable to residents of Niger. This explains why Israel is an outlier among developed countries.

Sci-fi books often have Earthlings exploring the universe in the year 3000. But I never see sci-fi books where most of the starship crew is Amish people, Haredi Jews, and Africans.

Seriously, it’s foolish to extrapolate current exponential growth rates, as the one constant in fertility is unexpected change.

READER COMMENTS

Fazal Majid

Sep 4 2022 at 4:21pm

Your income do not matter when the cost of housing has become all but unaffordable to the younger generations who can have children, and the cost of education matters as well. Both have risen well above inflation in the Western world, in which I include Japan and Korea.

Israel is indeed an outlier and the demographic shift towards ultra-orthodox Jews is a matter of grave concern to the state, since they were historically marginalized from society, education and high-income professions because in Israel military service is where interpersonal networks are built, much like universities in the US. Thus efforts to voluntarily extend military service to them.

Scott Sumner

Sep 4 2022 at 6:45pm

Are you saying that Korean housing was more affordable in the 1950s? In that case, why do modern Koreans have so much better housing than their grandparents?

I’m afraid you’l need a better explanation.

In any case, it’s easy to put two children into one bedroom—that’s how I grew up.

john hare

Sep 4 2022 at 7:30pm

In my opinion responsible people are the ones that tend towards success. Successful people beget successful nations. Increasingly it is expected that responsible people shoulder a much higher cost of raising children. A concern about being able to do that puts a damper on wanting kids.

A second thing often mentioned is that kids used to be producers from an early age improving the lot of the family. I was doing part time stuff for the family at 8-9 years old. First full time was in the summer of 1968 when I was 11. Today that would be called child abuse with all kinds of legal issues coming down. Dropped out of 6th grade at 12 (working with my parents) and have been working full time ever since.

My experience was common in the generation before me and virtually unheard of in the generation after. When children are a financial asset, it’s a different attitude from when they are a financial liability.

Jose Pablo

Sep 5 2022 at 12:10pm

“the cost of housing has become all but unaffordable”

Then, who is buying / renting the existing houses? I never understand this kind of sentences: if something is expensive it has to be because there is a lot of demand for this good or service. But for something “unaffordable” cannot be a “huge demand” (by definition of unaffordable). Now I am a little bit confused: why so many people can afford the “unaffordable”?

My grandfather grew up in a two bedroom and a kitchen house with no indoor plumbing. He was living there with his parents and his ten siblings. When he married my grandmother, they moved to a much bigger and better house where they had only two children.

That’s, very likely, South Korea housing-fertility evolution in a nutshell. The correlation between house affordability and fertility rates seems to be precisely the opposite of the one that you suggest.

Matt G

Sep 7 2022 at 11:22am

Jose,Unaffordable for most people, certainly. People who already owned homes can afford to move in to new homes. Additionally, just 22 years ago in 200 the median household income was about $42K and the median home price was $165K so let’s call it 4X. As of today, the median household income is about $68K and the median home price is $440K. The same house now takes an additional 50% to buy relative to household income. It’s 1.5X as hard to buy a house than even 20 years ago, let alone 30, 40, or 50 years ago.Additionally, investors are buying homes. Look at the affordability of housing since the inception of AirBnB and VRBO. It has plummeted because so much inventory has been taken of the primary residence market. Over 1M housing units in the country are used as short-term rentals. That’s just short-term rentals and doesn’t consider long-term rentals.

Jose Pablo

Sep 7 2022 at 8:00pm

“Unaffordable for most people”

No, most people live in existing houses and apartments. I bet they don’t live in places they cannot afford. That “most” make no sense at all.

There are 3.5 million apartment units in NYC. I am pretty sure that there are no more than 7 million people (assuming, on the safe side, an average occupancy of 2 persons per apartment) living in the streets (which is what would be required for the “most” part of your sentence to be true).

“Look at the affordability of housing since the inception of AirBnB and VRBO. It has plummeted because so much inventory has been taken of the primary residence market”

There are 10,000 apartments listed in AirBnB in NYC. That’s around 0.3% of the whole stock of apartments. And, in some of them, people keep living, just rent them out when they are not there (wonderful economic idea, by the way!).

And in the absence of Airbnb and Vrbo, more primary residences would have been taken down to build hotels. And, in any cases, assets should be devoted to their most valuable use. That’s intrisically good.

Regarding affordability, you get your numbers wrong, the key figure is not what part of your salary you need to pay for your rent or your house. The key figure is what part of your salary that you don’t need to use to things that you value more than your house you need to pay your rent or your house.

Houses and rents are more expensive precisely because people choose to devote more of their money to rent or buy houses. If most people couldn’t, houses (buying or renting) will not fetch the prices they do. How come?

Andrew_FL

Sep 4 2022 at 5:39pm

I don’t know for sure but I would guess more of the five children a South Korean woman would have ca 1950 would’ve survived to adulthood than the the 7 a woman from Niger has today will. Those families aren’t as large as the fertility rate would suggest…

Scott Sumner

Sep 5 2022 at 12:13pm

I don’t agree. Even in very poor countries the rate of child mortality has fallen rapidly. I’d guess about 4.5 survivors in 1950s Korea and about 6 in modern Niger—but someone correct me if I’m wrong.

robc

Sep 5 2022 at 1:00am

While it doesn’t fit your requirement, Vernor Vinge’s A Deepness in the Sky has primarily asian names. It is also an excellent novel. And won The Prometheus Award for best libertarian novel.

Scott Sumner

Sep 5 2022 at 1:56am

Yes, it’s a good sci-fi novel. I would not call it a good libertarian novel, as novels and politics mix like oil and water.

robc

Sep 5 2022 at 8:00pm

I think it is an excellent libertarian novel precisely because it doesnt preach any particular politics.

I have described the main theme as “**** off, slavers”. Can it be more libertarian than that?

Scott Sumner

Sep 7 2022 at 5:23pm

OK, but lots of people view slavery as evil.

BTW, I view almost all literature (and film) as vaguely liberal in the sense of allowing us to empathize with the suffering of others. (Not liberal in the “left wing” sense.) Before novels were invented (around 1600?), aristocrats cared almost nothing for the suffering of the lower classes. Film and TV have pushed this empathy even further.

robc

Sep 7 2022 at 8:52pm

Not enough to get rid of the income tax.

Chattel slavery is clearly worse than the income tax, but its a matter of degree. FOCUS was much, much closer to the former, but still somewhere on the continuum.

The phrase I used to describe the novel (but without the stars), is what I use for anyone wanting to control any aspect of my life.

BC

Sep 5 2022 at 2:01am

Given the very consistent pattern that fertility rates decline as countries become richer, it seems more accurate to say that wealthy (by global standards) Koreans can afford to *not* have lots of kids rather than to claim that they can’t afford to have kids. As John Hare alludes to, in poorer societies a significant portion of kids’ human capital value accrues to the parents. Kids both work in the family business, e.g., family farm, and also provide retirement benefits to the parents as adults. As countries become wealthier, they can afford the morality of limiting child labor. Wealthy countries also tend to socialize old-age entitlements. Instead of adult children financially supporting their retired parents, adult children end up supporting everyone else’s retired parents. Both child labor limits and socialized old-age entitlements reduce the share of kids’ human capital that accrues to parents.

Many conservative religions frown upon birth control. So, even as countries become wealthier, members of such groups may still find it difficult to have fewer kids because doing so would require limiting sex. That may be a price that proves “unaffordable” regardless of how wealthy a country becomes.

Mactoul

Sep 5 2022 at 2:54am

Does this inverse correlation of wealth and birth rate hold within a country as well?

Or maybe it is the middle class that is more squeezed out in matter of births relative to both rich and poor classes.

Scott Sumner

Sep 5 2022 at 12:08pm

“Given the very consistent pattern that fertility rates decline as countries become richer, it seems more accurate to say that wealthy (by global standards) Koreans can afford to *not* have lots of kids rather than to claim that they can’t afford to have kids.”

Great comment.

Rajat

Sep 5 2022 at 8:40am

I don’t understand the mechanism here. Why should more children reduce average success? Surely parents don’t believe that their own personal exhortings make much difference. And if the issue is money to spend on textbooks, tuition and tutors, that just comes down to money, which South Koreans now have much more of.

Scott Sumner

Sep 5 2022 at 12:10pm

That’s also my view, but lots of people suggest that this is a factor. (Costs of hiring expensive tutors, etc.)

Nick D

Sep 6 2022 at 6:23am

This is very much against a lot of anecdotal evidence from my life. People want to pay for private schools for their kids to get ahead, they want to buy or help their children buy a property too. That is genuinely hard to afford for 2+ children unless you are much wealthier than average.

There is a correlation between lower births per woman and increased female labour force participation within a country over time, if its causal the causality could run either way of course. That doesn’t seem to hold up across countries though, Korea’s female labour force participation and fertility are both low.

Jose Pablo

Sep 5 2022 at 12:20pm

“I am agnostic on the optimal fertility rate”

That’s extremely sensible. And, yet brilliant people don’t hold this position as often as you could expect.

The optimal fertility rate should tend to be very close to the actual fertility rate that people “decide” in a given economic environment. I don’t see any obvious reason why couples can not make the “right” decision when balancing the utility they get from having children and the utility they give up by doing so.

Granted it is an ex-ante decision based on very difficult forecasts on future utility. But so they are most of the decisions we make in live. And we don’t need “experts” second guessing every under uncertainty ex-ante decision that we, humans, make.

Scott Sumner

Sep 6 2022 at 1:00pm

That’s also my view.

andy weintraub

Sep 5 2022 at 7:24pm

I think we need to focus on the cost of having children. One important component of that cost is work opportunities for women. In South Korea and the U.S. as well, those opportunities raise the cost of having children. Among Hasidim women, after marriage, the tradition is not to work, thus lowering the cost of children to them because they can’t take advantage of a growing economy’s work opportunities.

Michael Rulle

Sep 6 2022 at 7:51am

I do not have a real answer for the cause of this phenomenon——but the correlations suggest avenues for analysis. The poorer a nation or a group of people are, the higher the birth rate.

The wealthier a nation or a group of people are, the lower the birth rate. I am pretty sure this is a solid fact. Also, the more religious a people are ——usually what one might call very traditional religious beliefs, the higher the birth rate. I think this is a much smaller subset than the wealth numbers.

I have no theory—-at best speculations. But I do not believe it is not random—-and I believe the answer is very complex——as it is likely a combination of policy by government and beliefs or objectives by people.

Also, within these macro numbers, analysis of who are more likely to have more than replacement births is likely related to something very specific.

I have seen many (or any) studies on this——-and yet it is an extremely important topic.

Michael Rulle

Sep 6 2022 at 7:55am

PS—-boy, do I wish you would permit edits——I need to make myself be more careful —-above I meant to say “it is not random”—I.e., I believe there are reasons for the phenomenon.

Michael Rulle

Sep 6 2022 at 7:57am

PS2–I have NOT seen studies. Jeez.

Joe

Sep 6 2022 at 11:38am

Have you never seen “History of the World”? “Jews in Space? Maybe Mel Brooks got it right.

paulmc

Sep 7 2022 at 11:04am

If I wanted to take an extreme devil’s advocate position, I would say that educating girls well has been a disaster, in the sense that no nation has educated its women and not immediately got on a path to extinction. There is simply no point in having all Korean girls be well-educated if there is not going to be a Korea in 50 years because those well-educated women are close to the last generation.

T Boyle

Sep 9 2022 at 4:00pm

Andy Weintraub nails it. The opportunity cost of having children rises with increasing wealth. It’s not a question of whether you “can afford” to have children by lowering your standard of living to what your grandparents had: it’s a question of the difference between the lifestyle you can have without children, and the one you can have with them. In developed countries, women have substantial opportunities to generate income outside of childraising, AND children have become insanely expensive, intensively-parented “pets”. For both reasons, women are having far fewer children – even stay-home moms. It’s not just because of birth control: birth rates fell even where it wasn’t available – but it surely helps.In an effort to encourage women to stay home and have children, western governments changed their family laws between 50 and 70 years ago to make traditional motherhood much more attractive, which did work to an extent. But, after three generations of watching how modern family laws devastated so many men in their fathers’ and grandfathers’ generations, younger men have shied away from marriage and family: the opportunity costs are enormous. The press and policymaking circles tend to focus on women’s decisions, but men matter too – and today, it is men who are far less likely to want to have a family (dating websites have the stats and they’re very clear). Men used to see marriage and children as a mark of manhood; now, many see them as an economic black hole with little long-term upside.Women don’t want to have children because they face huge opportunity costs. Shifting those costs over to their husbands and/or the fathers of the children is starting to fail, because men care about incentives too.If society values children, it’s going to have to make it much more attractive to have them. I imagine it’s not willing to force children to support their parents’ retirement (thus giving children value but turning them into human income-generating assets, which is problematic). The alternative will mean – somehow – subsidizing motherhood in some other way (and, if society wants men to participate, it will need to stop – in effect – brutally punishing them for doing so). And not in a tinker-at-the-edges way, but in a substantial one. Whether that should be a tax rate differential (promotes child-raising among educated women with very high opportunity costs) or straight subsidy (promotes child-raising among women with lower opportunity costs) is a policy question.

T Boyle

Sep 9 2022 at 4:59pm

Andy Weintraub nails it. It’s about opportunity cost. It’s not a question of whether you “can afford” to have children at the standard of living your grandparents had: it’s a question of the lifestyle you can have without children, and the one you can have with them.In developed countries, women have substantial opportunities to generate income outside of childraising – but, culturally we demand MUCH more intensive parenting than we did up to the ’70s (likely, driven by at-home moms feeling pressured); and cultural and legal requirements for spending on children have risen dramatically. It makes sense that women – even the at-home moms – are having far fewer children. In an effort to encourage women to stay home and have children, in the middle of the last century western governments changed their family laws to make traditional motherhood and financial dependency on a husband much more attractive, and this did work to an extent: “women’s lib” lost momentum in the ’80s and people are still telling little girls they can be anything they want when they grow up.But, after three generations of watching how those family laws devastated men in their fathers’ and grandfathers’ generations, younger men have shied away from marriage and family: incentives matter to them, too. Men once saw marriage and fatherhood as the mark of manhood; now, many have things they’d rather do than indenture their lives to a woman and 1.8 children. The press and policymaking circles tend to focus on women’s decisions, but today it is men – more than women – who are reluctant about family (dating websites have the stats and they’re very clear). Women hesitate to have children because they face huge opportunity costs if they devote their lives to child-raising, as our culture now demands (despite there being far fewer children). Family law was supposed to fix that, but it just meant that men increasingly don’t want to have children – or wives, either. If society values children, it’s going to have to make it much more attractive to have them. I imagine it’s not willing to force children to support their parents’ retirement (thus giving children value but turning them into human income-generating assets, which is problematic). The alternative will mean – somehow – subsidizing motherhood (and, if society wants men to participate, it will need to stop – in effect – subsidizing women by brutally penalizing men). And not in a tinker-at-the-edges way, but in a substantial one. How – for example, whether the goal is to promote childbearing by women with very high opportunity costs, or by women with lower opportunity costs – is a policy question.

Alexander Turok

Sep 20 2022 at 9:06am

South Korea had a lot of sex-selective abortion back in the 1980s and 1990s. This means there is an abundance of men and makes it easier for South Korean women to delay marriage.

Comments are closed.