How Should Econ 101 Be Taught?

By Donald J. Boudreaux

Chetty does not say that mainstream economic theory is irrelevant and, hence, dispensable. Yet he clearly believes that this theory is overrated, overemphasized, and overused relative to analyses of empirical data. To help remedy this perceived problem, Chetty developed and teaches a new undergraduate course at Harvard: “Economics 1152: Using Big Data to Solve Economic and Social Problems.”2

Because his course is meant to be an alternative—indeed, a better—introduction to economics than a traditional course in ECON 101, no economics-principles course is prerequisite for Chetty’s offering. Students who are completely innocent of any formal economic theory whatsoever are invited to enroll in Chetty’s course and be led by him not only to analyze lots of data, but to do so in ways that will enable these students to (quoting from the title of the course) “solve economic and social problems.”

Heady stuff for undergraduates! Yet it’s very bad stuff both for economic education and public policy. The notion that data can be sensibly analyzed independently of theory is naïve, as is the related notion that students can learn an adequate amount of sound theory through the analysis of data.

All Facts Are ‘Theory-Laden’

It’s trite to say—but now seems necessary to say—that data never speak for themselves. Never. Human beings make sense of empirical reality in whatever form, including the quantitative, only by sorting and processing it with mental models—that is, with theories. Most of the theories that we use in our daily lives are informal: gravity is constant and mothers are biased in favor of their children. To learn these and other such features of familiar reality requires nothing more than being a human being with some life experience. And so even those of us who have never experimented with stepping off a high cliff and who have never encountered a letter of recommendation written by an applicant’s mom understand that the former is suicidal and the latter is unreliable.

But to make sense of the vast range of reality beyond such basics requires theorizing that’s more formal. And so it is with the inconceivably complex reality that is a modern economy. Anyone hoping to get a useful mental grip on economic reality must begin by theorizing. There is no avoiding this reality.

Yet Chetty’s efforts to educate seem to be motivated by the assumption that one can indeed begin instead by examining the data, and through this examination discover how the economy works. From this discovery one can then, presumably, infer theories about economic reality.

But this approach is worse than wrongheaded; it’s impossible. Every human encounter with empirical reality, including with data, is an encounter necessarily filtered through the human mind. That mind can make no sense of even the simplest array of data without some mental model for sorting those data and drawing meaning from them. The only choice, then, is whether the mental model used will be selected willy-nilly and with no awareness, or carefully chosen according to its likelihood of enabling the person who encounters the data to draw useful insights and conclusions from them.

Every student entering Chetty’s data-analysis course has in his or her head, whether that student knows it or not, some theory about how the economy works. This fact is true no less for students without any previous exposure to formal economics than it is for students who’ve aced ECON 101. The only difference between the two kinds of students is that the former group—those with no exposure to formal economics—are much less likely than are the latter group to draw ‘correct,’ internally consistent, and useful conclusions from the data. Students with at least some exposure to formal economics have a better mental model for sorting the data and drawing deeper meaning from them.

The long and short of the matter is that no one has any business drawing from data any conclusions about economic reality without first mastering basic economic theory. Of course, one’s theory can—and should—be modified in light of observed empirical regularities. But the notion that a person observes first and only then begins to theorize is simply mistaken. Each of us always starts with theory.

Equilibrium versus Market Process Theorizing

The question now is: economic theory of what kind? Some economic theories are better than others. Unfortunately, modern mainstream neoclassical economic theory, although better than the completely untutored economic theories carried around in the heads of most people who’ve never taken ECON 101, leaves much to be desired.

In his essay on Chetty, Dylan Matthews rightly criticizes mainstream economists’ obsession with “mathiness and high theory”—features of mainstream economics that are symptoms of two unfortunate traits of this approach to economics.

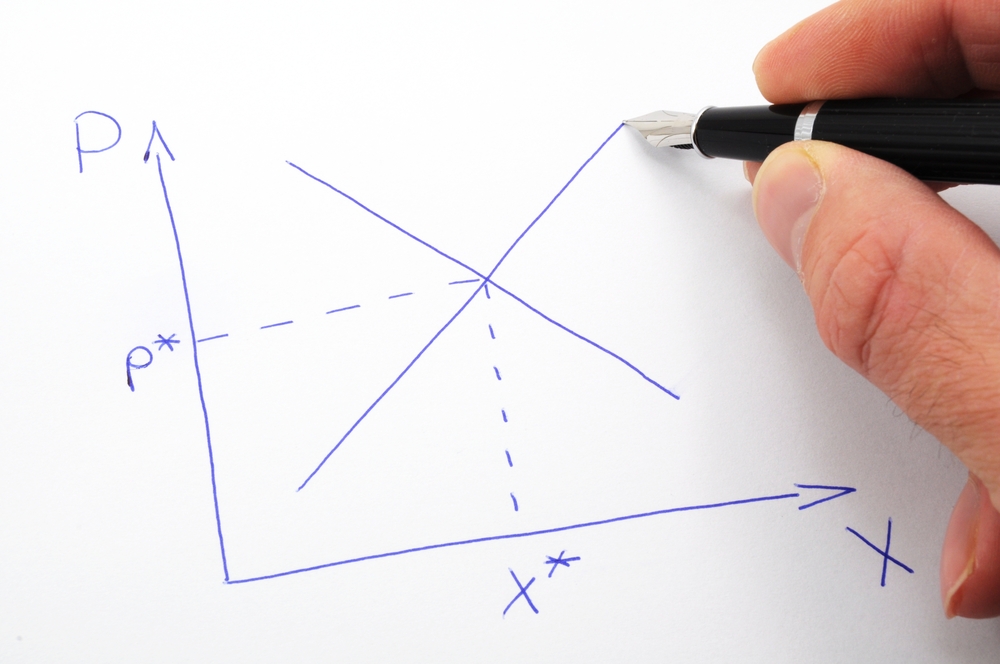

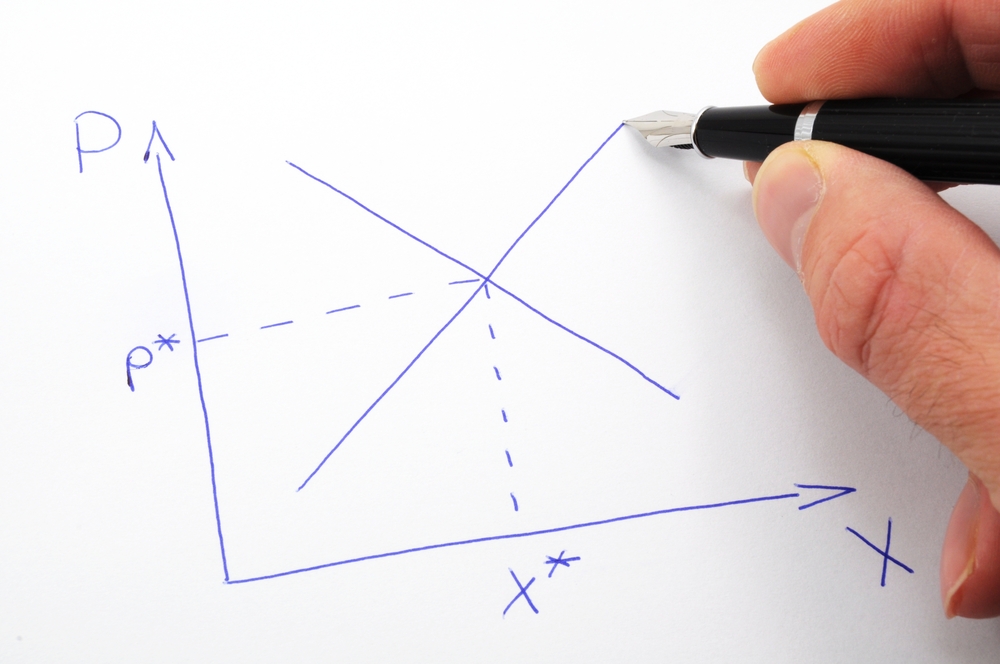

The first trait is an excessive focus on equilibrium arrangements. I was tempted here to write “equilibrium outcomes,” but “outcomes” implies processes that result in outcomes. Although (depending on which particular mainstream economist teaches the intro course) some informal mention might be made in class of the processes that generate economic equilibria, in intro-economics courses the processes of adjusting in real-world markets to the likes of shortages of milk, surpluses of labor, and inconsistencies between the plans of entrepreneurs and those of investors are almost never given center stage. Emphasis instead is put on describing the conditions of equilibrium (for example, “In perfectly competitive equilibrium price equals marginal cost equals minimum average total cost”) and on how to solve simple equations in order to determine equilibrium prices and other values.

The second trait is worse: it’s the careless presumption that reality’s complexity is adequately captured by the words, variables, graphs, and concepts used in economic theories. The scientific offense here is not the use of simplifying terms and assumptions. Every scientifically literate person understands that theories, to be useful, must abstract away from a multitude of reality’s details. The offense is that mainstream economists have forgotten that much that is relevant in economic reality results from details and complexities that are impossible to capture in theories in ways that enable economists to make specific predictions of the sort that chemists make when asked to predict the consequences of combining CO2 with H2O.

This forgetfulness, in turn, fuels all manner of empirical studies that are fundamentally flawed.

Here’s an example. To analyze minimum-wage legislation economists typically use a supply-and-demand graph. On this graph’s vertical axis is put “wage” and on its horizontal axis is put “quantity of low-skilled labor.” It’s then easy to show that a minimum wage, by reducing the quantity of low-skilled labor demanded by employers, causes some low-skilled workers who would otherwise be employed to instead be jobless.

Econometrically inclined economists then seize upon this proposition to test it empirically. Some empirical studies confirm this textbook prediction while other studies refute it.

But the vast majority of the researchers who conduct such studies treat the simplicity and unquestionable usefulness of this economic theory as being a reasonably full description of reality. This move is mistaken. In reality, employers can adjust to higher minimum wages in a number of ways in addition to simply employing fewer such workers. Employers can reduce the value of non-wage (“fringe”) benefits, or demand that workers work harder. Employers can also spend less money to ensure that workplaces are amiable and comfortable. To the extent that employers successfully adjust in these other ways, the quality of the jobs held by low-skilled workers are made worse, but the number of such workers who find themselves in the ranks of the unemployed will be less than if employers responded to higher minimum wages exclusively by employing fewer workers.

Getting reliable quantitative data on how employers adjust to minimum wages in these ‘other’ ways, however, is difficult and, often, practically impossible. (How seriously would you take a study the authors of which claim to accurately quantify small changes in the amiability and comfort of workplaces?) Yet because employers surely do adjust along these ‘other’ lines, studies that ignore these adjustments and that focus exclusively on the effect of minimum-wage hikes on the number of workers employed miss important negative consequences of minimum wages. Such studies might be indisputably correct in their findings of the effects of minimum-wage hikes on the number of jobs available for low-skilled workers, yet scientifically worthless—indeed, misleading—because they ignore all potential negative consequences of minimum wages save one.

Economists who churn out such flawed empirical studies can lay some blame for their misleading work on careless economic theorists and inept economics teachers. Because economic reality is inconceivably complex in its details, all economic theory—from high, Nobel Prize-level theorizing down to ECON 101 classroom lectures—necessarily must be conducted using concepts and words that are far simpler than the realities to which these concepts and words refer. Competent theorists and good teachers understand this fact about the concepts and words used in economic theory. And such economists ensure that this fact is also understood by their audiences and students.

What the Good ECON 101 Teacher Teaches

The good ECON 101 teacher, while agreeing that economics is ultimately about empirical reality, at this point parts ways with Chetty who supposes that to be scientific economics must be an empirical discipline in the same manner that medicine is an empirical discipline. The good teacher also parts ways with those mainstream economists who teach economics as a study of equilibrium outcomes.

The good teacher teaches that the market is a highly complex process. This teacher grasps a scientific fact that Chetty and many mainstream theorists do not, namely, that economic phenomena are so much more complex than are biological and physical phenomena that the empirical tools principally used to gain improved scientific understanding of the latter are of only very limited use in the former.

Sticking with the minimum-wage example (though the point applies widely), the good teacher uses supply and demand analyses to make clear an important aspect in which low-skilled labor is the same as any other good or service: if the cost of acquiring or using it rises, people become less eager to acquire and use it. What is true for apricots, aspirin, and alpine vacations is equally true for low-skilled labor. But this good teacher is careful also to make clear the significant, general point, which is that the artificially reduced attractiveness of employing low-skilled labor can play out in reality in many different ways, each one of which has negative consequences for low-skilled workers.

The good teacher of ECON 101 imparts to her students the understanding that the concepts discussed (such as “the equilibrium wage rate” and “the population of low-skilled workers”) and the analytical tools used (most notably, supply-and-demand graphs) are not to be taken literally. They are simplifications of complex real-world phenomena. But by skillfully using these simplified concepts we gain important and generalizable insights into market processes, as well as into what likely occurs when these processes are obstructed by government interventions.

The good teacher of ECON 101 is under no delusion that she is training students to become observers of a relatively simple objective reality of the sort that a teacher of Astronomy 101 trains his students to observe. The economy is far too complex to be ‘merely’ observed, or to be understood with minimal amounts of theoretical structure. The good ECON 101 teacher instead is aware of the intellectual prejudices and biases possessed by most non-economists—intellectual blinders that prevent people from understanding market processes—and seeks to free her students from these blinders.

Foremost among the lessons that students learn from such a teacher are these:

- – Goods and resources are scarce relative to human wants, and therefore nothing is free; while it might be worthwhile to produce more guns, there’s a price to pay in the form of less butter.

- – Reality isn’t optional, and life is a series of inescapable trade-offs. Just because some option has an upside does not mean that it should be pursued, and just because some option has a downside does not mean that it should be avoided. The most foundational question that the competent economist asks is: As compared to what?

- – Prices and wages set on markets are not arbitrary; they reflect underlying economic realities.

- – Prices and wages set on markets weave the self-interested choices and efforts of billions of individuals into a globe-spanning and largely invisible web of remarkably productive social cooperation—a web neither designed nor operated by anyone.

- – Individuals respond predictably to incentives: raise the cost to Jones of sunbathing and Jones will do less sunbathing; increase the benefits to Jones of saving money and Jones will save more money.

- – Preferences are subjective: the details of Jackson’s responses to incentives differ from Jones’s responses.

- – Almost all choices are incremental: do I want to drive a safer car or not? If so, I can improve my car’s safety incrementally by putting on new tires or changing my brake pads; I don’t have to buy a tank or even a new, top-of-the-line Volvo.

- – Choices are made only by individuals. Although individuals often choose to join with others in organizations such as clubs or political groupings in order to make collective choices, choices are never made by collectives as such; choices are never made by abstractions such as “the market” or “the People.”

- – The consequences of almost every human action extend not only beyond those that are intended by the actor, but also beyond those that can be foreseen. Therefore, intentions are not results, and results can neither be predicted nor fully understood by examining intentions.

- – And perhaps most importantly of all: The complexity of a modern economy is so vast that no human can begin to grasp it in any detail, and much less to ‘plan’ it or any large part of it. The best we can do is to understand the economy’s basic logic and record, humbly, some of its empirical manifestations.

Hayek’s “Curious Task”

For more on teaching economics, see “Economics Works,” by David R. Henderson. Library of Economics and Liberty, May 6, 2019.

See also the EconTalk podcast episodes with Paul Romer, such as Paul Romer on Growth, Cities, and the State of Economics, April 22, 2019.

The tragedy of economics as taught by Chetty is that it teaches almost none of the above. The danger of economics as taught by Chetty is that it falsely affirms the economically untutored student’s mistaken impression that the economy is a relatively simple set of things and relationships—a set of things and relationships that can be observed and learned chiefly through empirical study and then engineered to operate according to the student’s conception of how an economy ‘should’ operate. Armed with impressive-looking empirical studies of existing income differences, current rates of resource-extraction, and other only-apparently meaningful and objective economic ‘facts,’ Chetty’s students never learn about the mostly unseen, typically unquantifiable, and often awe-inspiring economic forces at work that spontaneously generate not only these quantified ‘facts,’ but also facts and responses and outcomes that even the most advanced econometric observations and processing cannot detect.

But ECON 101 should impart an understanding and appreciation of the economic forces at work in society. Indeed, imparting this understanding and appreciation is the greatest service that the economics profession can do for society. To learn this lesson is to learn that economic reality is a dynamic emergent order the complexity of which warrants humility. To learn this lesson, in short, is to internalize the truth of Friedrich Hayek’s 1988 description of the economist’s “curious task”: “The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.”

Economics as taught by Raj Chetty teaches the opposite: learn about a few artificially conceived aggregate empirical relationships and then fancy yourself fit to offer advice as a social engineer. It’s frightening.

Footnotes

[1] “The radical plan to change how Harvard teaches economics”, by Dylan Matthews. Vox.com, May 22, 2019.

[2] Available online at: Using Big Data to Solve Economic and Social Problems. Opportunity Insights.

*Donald J. Boudreaux is Professor of Economics at George Mason University and Senior Fellow with the F. A. Hayek Program for Advanced Study in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at George Mason’s Mercatus Center. He blogs at Café Hayek (www.cafehayek.com).

For more articles by Donald J. Boudreaux, see the Archive.