One of the mysteries of the universe is that it is logical. Whether in geometry, in physics, or in economics, purely logical theories explain the messy world. It is true that some theories are contradicted by empirical evidence, which suggests that they are not applied to the right problem, or that their assumptions have not been chosen wisely. Yet, some logical theories that seem at first inapplicable to the real world often end up finding applications; I understand that quantum physics provides numerous examples.

It is however as sure as anything can be that an illogical theory is false and useless. One illustration is what I called a logical prank in the protectionists’ trade-deficit fixation. In an article of the Fall issue of Regulation, I wrote:

The logical prank comes from begging the question, what is the problem with a trade deficit? It reveals unfair trade practices, answer protectionists. But how does a protectionist determine that trade is unfair? By observing that it results in a trade deficit. The evidence of a trade deficit and of unfair trade is self-referential.

A smaller mystery in the world is how accounting identities, which are logically true by definition, can be useful. The answer, I think, is that something adjusts in the real world to make the identity always true, and that this thing adjusts by definition of the thing. The identity called the “basic accounting equation” states that assets are equal to liabilities plus shareholder value: A=L+E (the two sides of a balance sheet are equal). This is always true because shareholder value is defined as the difference between assets and liabilities. Profit (or loss) is the residual that provides for the real-world adjustment.

When I was in graduate school, I read something to the effect that accounting is like religion: it always has an answer. I think the author was Kenneth Boulding, but I have never been able to find the quote. (I will send a copy of my latest book to the first one who finds the actual quote. Fine print: I will be the only judge of whether it’s the quote I am looking for!) I am not claiming that religion or accounting are useless.

Matters get complicated in national accounting, perhaps because of what motivated the creation and form of the national accounts (for a glance, see my “What You Always Wanted to Know about GDP But Were Afraid to Ask,” Regulation, Winter 2016-2017, pp. 64-69). In that field, many are tempted to consider an accounting identity as a logical theory that explains the real world without the need for empirical testing or good assumptions. It is true by definition! But national accounting identities, like accounting identities in general, should not be mistaken for theory.

The summit of accounting abuse must be to read an accounting identity incorrectly and then compound the error by deriving a theory from this faulty reading. As I explained before (including in my recent EconLog post “The St. Louis Fed on Imports and GDP,” September 6, 2018), such is precisely the error committed by those who use the national accounts identity GDP = C+I+G+X-M to conclude that imports (M) reduce GDP. In my Regulation article, I repeat this argument and use a brilliant analogy devised by Thomas Firey, the managing editor of Regulation and an occasional blogger on EconLog. My rendition of the analogy:

Think about the guy on the scales who subtracts 1 lb. to factor in the weight of his shoes; his weight doesn’t change if instead he subtracts 2 pounds because on that day he is wearing heavier shoes. Likewise, American output doesn’t change because more imports are both added and subtracted.

READER COMMENTS

Warren Platts

Sep 15 2018 at 1:23pm

Number one: whether a theory is logical or not is not what makes it true or false. Quantum mechanics is about the most illogical theory imaginable. It violates every norm of common sense: like a single particle going through two slits at once. Yet, in terms of its ability to predict the real world, quantum mechanics is the “most true” theory out there (if truth admits of gradations).

Similarly, a theory can be most beautiful and logical: yet if that theory is contradicted by the empirical evidence, it is not a matter of not being applied to the right problem, or that their assumptions have not been chosen wisely–the theory is simply false.

Comparative advantage is one of those beautiful logical theories. It is so beautiful and logical one is tempted to conclude that it impossible for the theory to be false. But this cannot be the case unless comparative advantage is not a scientific theory. A scientific theory, by definition, is a theory that is falsifiable.

Therefore, it must be possible for comparative advantage to be false. Moreover, as Ricardo himself pointed out, the theory is highly domain specific. The theory assumes certain circumstances, and when those circumstances are not present, we should expect the theory to yield false predictions.

Which brings me to the GDP equation: Y = C + I + G + X – M. The standard argument is that M is already included in C, and therefore, we must subtract that portion out in M in order that Y be limited to domestic production (hence the name Gross Domestic Production).

The problem is this line of thinking ignores another identitity C = Cd + Cf; total Consumption = Consumption of domestic production + Consumption of foreign production. Thus if a consumer buys a $40 foreign toaster instead of one domestically produced, Cf goes up by $40, and thus Cd must necessarily go down by $40. There is no free lunch, right?

This would not be a problem, if, as the theory of comparative advantage predicts, the toastermaker who loses his job gets a new job making exports, and X increases by $40. Indeed, an efficiency gain should be realized, and thus a modest consumer surplus should result.

But what if exports do not go up by $40? Well, or so the argument goes, the toastermaker will get a job as a programmer and maybe make $50 worth of code. But who is going to pay for it? The consumer who just bought the foreign toaster now has $40 less to spend on something else, including domestically produced code. After all, Cd is not just production–it is also income; one person’s expenditure is another person’s income. If expenditures go down, income, and hence production must also go down. The toastermaker gets a new job all right, but it is flipping burgers, and Y goes down by $40.

The free trader will typically counter this point by saying that if an economy is on its Production Possibility Frontier (PPF) the resources freed up when the toaster factory is shuttered must necessarily be put to some other (likely more productive) use. But what is the evidence for that? One can point to the currently low unemployment rate. But if we accept that criterion, then that entails for the last ten years(!) the economy has been below the PPF further entailing, evidently, that a suboptimal economy where resources are not being used optimally is the normal state of affairs for the USA these days.

But wait. As free traders are fond of pointing out, the $40 do not just sail away over the horizon. The dollars come back in the form of the capital account surplus. Thus, there really is something resembling a free lunch. We can increase Cf while keeping Cd the same, we just pay for the difference by putting it on the national credit card!

But there is still a cost. The general accounting equation is E = A – L; Equity = Assets – Liabilities. So either Liabilities gets more negative by $40, or Assets get reduced by $40. Either way, the bottom line E of the national balance sheet goes down by $40. Our net wealth is reduced.

There are thus 3 ways to pay for the $40 foreign toaster: (1) increase X by $40 as predicted by comparative advantage; (2) pay for it by reducing the domestic consumption budget Cd–in which case Y does indeed go down; or (3) reduce E by $40. Thus trade deficits (cases 2 & 3) matter: they reduce employment (2) or they maintain present consumption by reducing future consumption (3).

At this point, the final resort of the free trader is: So what? As long as asset values keep growing fast enough, what’s the problem? Indeed, they will point out that the trade deficit itself fuels increases in asset prices! The buying pressure drives up asset prices directly, and the flow of cash lowers interest rates and provides lots of easy credit, thus further fueling asset prices.

Well, we tried that experiment before, and it ended badly in 2008. Ten years later, we are still crawling out of that hole–now that we are overdue for the next recession.

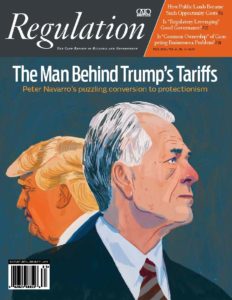

Peter Navarro is about the one economist who actually learned the empirical lessons that the last 30 years have wrought. He was able to change his mind. As have I. The ability to change one’s mind in the face of new evidence is ordinarily considered to be an admirable trait. But given that no professional economist has skin in the game when it comes to the actual economy itself (How many economists got laid off during the Great Recession?), there is no telling how many more busts we must go through before they finally catch on.

Dan Culley

Sep 16 2018 at 4:27am

Except that you are missing a fourth case: that M double doubts spending they is also in I, not C. It’s a critically important case, because investments produce net returns. And when they are equity investments, they do not raise foreign indebtedness, as you suggest–if the investment fails, there is nothing to repay. If there is a persistent abundance of higher return investments in a country relative to the rest of the world, then it can run a trade defecit forever.

And, in fact, this case–foreign direct investment–makes up the bulk of the US capital account surplus.

A current account defecit just means that investment exceeds savings. (GDP – I = C + G + X – M.) If that is because you are borrowing to finance consumption, as you suggest, indeed that can be problematic. But if it is borrowing to finance profitable projects, then there is nothing bad about that. And soliciting equity to finance profitable projects is even better.

Warren Platts

Sep 16 2018 at 6:05pm

This is a common free trade canard. In fact, green field investment in brand new factories is a tiny, tiny, tiny proportion of the total net foreign “investment” necessitated by the trade deficit. The Vast majority of foreign “investment” (that has nothing directly to do with the “I” in the GDP equation) goes into things like T-bills and FANG stocks and California & NYC & midwestern agricultural real estate.

As for FDI specifically (which is defined by foreigners acquiring controlling interests in US firms), in 2017, total FDI inflow was $277B. Meanwhile, US FDI outflow was $300B, entailing we ran a $23B FDI deficit for 2017.

As for us running a trade deficit “forever,” that ain’t gonna happen. The trade deficit will end sooner or later. The only question is whether the end will be managed, or whether we deliberately choose to let nature take its course. There will be pain either way, but the pain will be less with the former option. imho. ymmv.

Jon Murphy

Sep 16 2018 at 9:01pm

We need to be careful with the term “consumption” here. All borrowing is to finance consumption. Consumption is the end goal of all economic activity. One who borrows money to buy a house is borrowing for consumption. One who borrows money to purchase equipment is borrowing for consumption.

It’s also misleading to talk about a trade deficit as “borrowing” money. Trade deficits =/= debt. They may, but they do not necessarily have to.

To wit: Imagine A buys a car from a seller in Country B. The individual from B then uses those funds to buy land from another person in A’s country. This will result in a trade deficit (since imports exceed exports), but no debt is created whatsoever. No borrowing has occurred.

To the main point of this blog post, this mistake that trade deficits imply budget deficits and thus debt is one of the issues of treating an accounting identity like GDP as an economic theory.

Warren Platts

Sep 17 2018 at 3:36pm

This commonly made retort perpetrates something of a shell game. Financing present consumption through the sale of assets has the same effect as financing present consumption through debt: future consumption is reduced. An asset is something that generates cash flow. Thus when the farm is sold, the future income from that farm is lost, and hence the ability to consume that that income represents is lost. E = A – L. Whether the trade deficit is paid for by increases L or decreasing A, the effect on the balance sheet’s bottom line is the same. Present consumption is paid for by forgoing future consumption. If you are 80 years old, this is a good thing: you likely will not live to see the day of reckoning. If you are 8 years old, not so much.

Jon Murphy

Sep 17 2018 at 4:06pm

Why are we assuming the income from the asset is lost? Why would a foreigner trade a perfectly good item for something he intends to destroy?

Jon Murphy

Sep 17 2018 at 4:08pm

(Ironically you’re making the very mistake Lemeiux warns against).

Anyway, why are we also assuming a fixed stock of capital?

Warren Platts

Sep 17 2018 at 5:25pm

Yes, the field hands working for $7.25 an hour still receive an income, but the profits flow to the absentee landlord.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Absentee_landlord#In_Ireland_before_1903

As for fixed capital stock, what matters is the rate of capital acquisition. Last I checked 35% of U.S. equities are foreign owned. This is up big league from 10 and 20 years ago. Clearly, even though the U.S. capital stock is expanding, the rate of foreign acquisition is expanding even faster. It is not sustainable.

Jon Murphy

Sep 17 2018 at 5:41pm

Yeah. So? If there are profits, then the land is producing something of value. Thus it is adding to GDP (and those profits, since they are in dollars, necessarily will return to the US economy, increasing GDP). So, there 1) is no debt and 2) has an increasing effect on GDP, not decreasing

Uh, except by definition it is.

Hazel Meade

Sep 18 2018 at 4:18pm

<i>Present consumption is paid for by forgoing future consumption. </i>

I don’t think this is accurate in the case of the trade deficit. What the current account deficit means is that foreigns hold US dollars, which means they must eventually spend them on US made products. Future production might be vastly higher than present production so future purchases of American made products don’t necessarily force Americans to forgo consumption. I could imagine a future where foreign demand drives up prices of products to the point that Americans cannot afford them, but it seems unlikely. Much more likely is that we can produce extra stuff and it gets purchased. Alternatively, foreigners might buy US debt – but the more demand there is for US debt, the lower we can set interest rates. In this case, this isn’t necessarily us going hat in hand to them to borrow money – this is them looking for a place to park the US dollars they hold and US setting the terms.

Warren Platts

Sep 18 2018 at 7:02pm

“by definition”

By definition, there are only 100 pps in 100%. So if 35% of equities are foreign owned now, and the foreign ownership triples again in the next 20 years like it did in the last 20 years, then 100% of all US equities will be foreign owned. At that point, there will be no further increase in the percentage foreign ownership. Therefore, rate of growth of foreign ownership that exceeds the growth of the capital itself is not sustainable.

And this is wrong on multiple levels. You admit that debt is bad–it reduces future consumption because it must be paid for with future production, but you are trying to make the case that asset sales are somehow good, or at least not bad.

My claim however, is that the practical effect is the same in that asset sales used to finance present consumption also reduces future consumption. The lost income represented by the profits that flow overseas represent an opportunity cost that is every bit as real as the cost of debt payments.

Moreover, your claim that the farm purchase increases GDP is simply false. It has zero effect on GDP, unless the foreigner makes additional investments that will increase the land’s productivity. (And the stereotype is that absentee landlords tend to neglect improvements, thus reducing productivity and GDP).

What does happen is that the loss of the profits lowers GNP. GNP is GDP plus net foreign income. So the profits from that farm get repatriated to the foreign country, increasing that country’s GNP, while reducing USA’s GNP. And unless that money comes back in the form of export purchases, that reduces the funds available for consumption of future domestic production. Just like debt.

Now you will say those dollars must come back somehow. But that mere fact in no way distinguishes asset sales from debt. The foreigner sells us consumer goods on credit. We pay him back in dollars, those dollars have to come back, and if it is not in the form of export purchases, it is the form of more debts and asset sales.

Indeed, from the perspective of the foreigner, the loan is an asset. That is, creating the debt creates an offsetting asset, and so even going into debt to pay for present consumption is literally the sale of an asset. Thus the distinction melts away entirely.

As for Hazel’s contention foreigners might at some point in the future buy a bunch more U.S. production (exports I guess). But how exactly is that supposed to happen? That would require us to run a trade surplus in the future. And there are only two ways for that to happen: (a) the USA goes back to its mercantilist roots, and uses every trick in the book to ramp up export production; or (b) consumption of imports goes into the toilet because of the impending financial crisis, the root cause of which will be the trade deficit.

We really do not want to do the latter. The economic upheaval will be tremendous. Real wages will dive, unemployment will be sky high. We will be like Greece or Spain is right now. They are now running trade surpluses, but they are not happy campers; their GDP is still down after 10 years.

Jon Murphy

Sep 19 2018 at 8:57am

Actually, I explicitly say the opposite: debt is not necessarily bad.

Yes, we know that is your point, but it is factually incorrect (and you acknowledge this point is incorrect: “It has zero effect on GDP, unless the foreigner makes additional investments that will increase the land’s productivity,” [this point is also incorrect, as we note you rely on a stereotype rather than any actual evidence or theory to make your claim] as we explained and you ignored.

Fine, but now you’re playing a shell-game. Up to this point, you’ve been doing nothing but crying about GDP. Trying to subtly shift not to GNP (oh, and you’re still factually and theoritically wrong on the effects on GNP) is to change the topic.

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 16 2018 at 11:41pm

It seems to me that many of your objections, I answered in advance (or I tried to) in my Regulation article.

When you say “thus Cd must necessarily go down by $40,” you defend a Keynesian theory on the basis of an accounting identity. My point is that the theory of comparative advantage is more defensible and is consistent with this national income identity. Different components adjust.

You might also have a look at, or reread, my previous post on St. Louis Fed’s Scott Wolla take on this, and my reply to our commentator Ahmed Fares.

You raise some interesting questions about the “national balance sheet”—assuming that such a thing exists and is represented by the balance of international indebtedness.

Warren Platts

Sep 17 2018 at 4:58pm

Yes, I saw Ahmed’s and your comments on the St. Louis Fed article, hence my allusion to the $40 toaster. You say if the toastermaker who loses his job becomes a programmer and makes $50 worth of code instead, then GDP goes up by $10. But I think that is only the case if the $50 worth of code is exported. If it is not exported, then it is paid for by Cd.

But aggregate demand, represented by Cd, has gone down by $40. So even if the programmer sells his code to a fellow citizen, the dollars that he receives are dollars that some other producer did not get, and so forth. So yes, it is rather like how Keynes describes the effect of money hoarding: whether stuffing $40 into a mattress or shipping it overseas for a toaster, the effect on the local economy is the same: the velocity of money goes down, employment is less than it otherwise would be.

As for comparative advantage, I think we have to say that to the extent that there is a trade deficit, comparative advantage has broken down to that extent. Consider Ricardo’s example where all production of both wine and cloth shifts to Portugal. England would then pay for all of its consumption through debts and asset sales–a rather odd national specialization. It is the same for the consumption of imported goods in the U.S. that are paid for by debt and asset sales–that is our national specialization, if you want to call it that.

The result is a reduction in the national balance sheet. This is pretty much measured by NIIP: Net International Investment Position. It is basically the sum total of all our past trade deficits, adjusted for value. It currently stands at about minus $8 trillion, or ~40% of GDP. Note that this is much higher than during the Great Recession (~20%). In 2007, it was only ~10%. If the rate continues, we would be at ~70% of GDP in another ten years.

The thing is, NIIP/GDP is a rough measure of a country’s creditworthiness. When large countries get a negative NIIP of more than ~60% of GDP, bad things tend to happen. Foreign investors will lose confidence in your economy, and begin to pull their funds. Contagion creates panic. Then you have a fully fledged financial crisis on your hands. Asset prices fall into the basement, and people stop buying everything, including imports, and voila: your trade deficit goes away, naturally, through the workings of the free market! But your economy is now in the midst of a major depression…

This is why I humbly suggest we at least try to unwind the massive trade deficit. The ROW will be mad as hell at us for no longer accepting their unemployment exports, but the reality is they will be better off in the long run if we can fix this thing. If you all think that tariffs are not the solution, then by all means propose something else. But pretending there is no problem (a) short-changes our workers in the short run; and (b) can only lead to big trouble in the not-too-distant future.

Jon Murphy

Sep 17 2018 at 5:43pm

Nothing about comparative advantage suggests there would be no trade deficit. Nothing whatsoever (further, Ricardo was incorrect to suggest all production could/would shift. Interestingly, he seems to have missed the key insight of his model).

Hazel Meade

Sep 18 2018 at 3:57pm

I may be rusty on my Ricardo, but I think the point of his example was that it would make no sense to have 100% of production shift to Portugal, and leave all the English workers idle. Instead, the English workers would be employed making whatever they were *least bad* at. They would simply produce extra wine or extra cloth, raising the net total production. Which would mean there would be in total more win and cloth for English workers to enjoy.

Similarly, even if American workers are the worst at producing everything, it would make no sense to have American workers remain idle. Those workers would wind up being employed doing something else which would add to the net amount of goods and services available to American consumers in the US.

Warren Platts

Sep 18 2018 at 6:12pm

Mr. Murphy missed the point entirely–and no, Ricardo did not make a mistake, nor is there a published paper that says as much. In fact, Samuelson, in his “Theoretical notes on trade problems” said the same thing: “If our wage levels stay high enough, we can be undersold in every good. Without transport protections, our employment could be zero. The whole of our imports would then have to be financed by capital movements” (my emphasis). And in that case, what exactly is our national specialization? The very idea does not make any sense; there is no comparative advantage.

Of course Mr. Murphy will give one of his “by definition” arguments that it is theoretically impossible for there to not be comparative advantage. However, his point is true if and only if the immobile factor, labor, allows its wages to sink way below the current minimum wage until is at parity with developing nations. But then trade in manufactured goods ceases altogether, to be replaced by trade in some raw materials, agricultural products, and energy.

Yes, the example where a country offshores all manufactured goods production is extreme, and perhaps unlikely–although by no means a theoretically impossibility, as Samuelson proved in his paper. Moreover, the USA is well down the road on that path: US consumption of manufactured goods is close to twice US production of manufactured goods–including exports. So a large majority of the total manufactured goods consumed by Americans is foreign made. And exports do not begin to make up the difference.

Hence my claim that to the extent that there is a trade deficit, then comparative advantage has broken down as a theory. If 100% of all goods are imported, and paid for by capital movements, then comparative advantage has broken down completely, because there is no national specialization, unless one is prepared to say that selling T-bills, other bonds, stocks, and real estate is a “national specialization”.

At the other extreme of the spectrum, trade is balanced, country A specializes in making good Y, and country B specializes in making good Z. Efficiency gains are realized, and comparative advantage has worked as predicted. In the middle of the spectrum, you the have USA as it is today: it exports a lot of planes and soybeans, and to that extent, comparative advantage is working; and to the extent that we have an $800 billion goods trade deficit it is not.

It is not a Manichean question of all or nothing. It is quite possible for comparative advantage to sort of work, and to sort of not work. It is sort of working for the United States, but there is a lot left to be desired. And no, lowering wages lower than they have already been lowered in order that comparative advantage will “really” work is not an option. Moreover, if comparative advantage is not working as optimally as it should, then the case for necessary net gains goes out the window. In fact, it is not clear at all if the USA has received net gains over and above what it would have been if we had maintained the American System of economics over the last 50 years.

In fact, GDP growth has been slow, especially since 2000. The headline unemployment rate is down, to be sure (finally after ten years), but overall employment of prime age workers is still down, and wages are not going up in real terms. And under such circumstances: “With employment less than full and Net National Product suboptimal, all the debunked mercantilistic arguments turn out to be valid. Tariffs can then reduce unemployment, can add to the NNP, and increase the total of real wages earned.”

Jon Murphy

Sep 19 2018 at 9:01am

You needn’t believe me. Just think about the logic of the model.

Using the Stolper-Samuelson model, (or Hecksher-Ohlin, or any other model you so wish), explain to me why your statement is incorrect. This mistake is covered in Chapters 2-6 of the Krugman, Obstfeld, and Meltz textbook).

Hazel Meade

Sep 18 2018 at 4:10pm

What you are missing is that (first) the toaster is an object of tangible value which people are getting in exchange for the money, and (second) that the toaster must be cheaper than the US made toaster to remain competitive.

Hypothetically the US made toaster would have cost $50, but you would say that $50 would stay in the country and employ some US person right? But if it leaves the country – we still get a toaster in exchange for it! So $40 gets spent, but we get a toaster, AND an extra $10. We’re basically up $10. Now the labor that is freed up by not making toasters might not all be employed writing code – there may be some marginal negative impact on employment and wages, but the extra $10 that gets added to the economy makes up for that – and the consumer who gets the toaster and whatever he gets for the extra $10 benefits directly. Not everything is about GDP.

I’m beginning to think that measuring prosperity in terms of domestic production is generally wrongheaded. Under that measure leisure time and quality of life count for nothing. Quality of life is not measured by the number of pies you produce, but by what you are able to afford with the money you get from selling them.

Warren Platts

Sep 18 2018 at 6:32pm

Hazel, I see what you are saying, and you raise a good point: that the ultimate goal of economic activity is the quality of life satisfaction, or happiness that it enables. Yes the consumer of the foreign toaster gets a toaster and a $10 consumer surplus. Nevertheless, unless the former toastermaker gets a job in exports, aggregate demand for goods is still down by $40.

My claim is that this has the same effect on the economy if another person simply keeps the $40 in a coffee can (or T-bill) and does not spend it. I think you will say that the economy is better off in the first scenario, because at least they get a new toaster. But that is not the case. The person hoarding the $40 gets more satisfaction/happiness knowing they have a $40 insurance policy against a future rainy day.

Thus the effect on the domestic economy is the same: it is deflationary. Y = C+I+G+X-M, but it is also the case that Y = MV, where M is the money supply, and V is the velocity of money. Hoarding cash lowers V, and hence Cd, and hence Y. I claim that imports that are not paid for with exports have the exact same effect: V, Cd, and Y all go down. (Unless, of course, you artificially stimulate V by going into debt or selling off pre-existing assets, but that cannot be a permanent strategy.)

Thus it is fine if you want to say that M has no “direct” effect on GDP, but that does not make the above indirect effects go away. imho ymmv

Jon Murphy

Sep 19 2018 at 9:02am

Again, no it’s not. You really lack even the most basic comprehension of the models you are discussing.

Warren Platts

Sep 19 2018 at 10:28am

Yes, it is, for the good reasons I stated above. You just made 4 comments, not one of which contains something resembling an actual argument. Only mere assertions, deflections, ad hominems, and bland word salad.

Hazel Meade

Sep 19 2018 at 1:51pm

The former toastermaker needn’t get a job in exports – he could be doing something that the consumer of the toaster purchases with the other $10.

Warren Platts

Sep 19 2018 at 3:27pm

EXACTLY! That is indeed the main protectionist argument. It is not that jobs are lost entirely–although there is a little bit of that, The main thing is that people in the manufacturing sector are forced to take jobs in the service sector. Thus, your example is about right: the output per person in the manufacturing sector is about 4 times the output per person in the service sector. So toastermaker gets a job as a burgerflipper making a $10 burger in the time it used to take to make a $40 toaster precisely because the toastermaker cannot get a job in export manufactures because the foreigners are not buying. This is the microeconomic reality that we claim has the macroeconomic effect of slowing GDP growth.

Jon Murphy

Sep 15 2018 at 3:18pm

Excellent post (as always).

I think it’s also important to consider what is driving said accounting identities. For example, if GDP increases, say, 4% because people are producing more and expanding their consumption possibilities, that is a desirable outcome. If, on the other hand, GDP increases 4% because government is spending money to dig ditches and fill them back in, then that is an undesirable outcome as it will result in wasted resources and stunted growth. But GDP would record both as identical (even ignoring the issues of treating imports as a subtraction to GDP, even if we assume they are all substitutes for domestic production, this is similar to the mistake people make regarding imports and GDP).

Aggregate measurements like GDP are only valuable insofar as they are allowed to report underlying actions. the moment they become an object of choice, they lose all value.

PS: I’m trying to find that quote for you so I can get a “free” book, but MC is quickly approaching MR here 🙂

Weir

Sep 16 2018 at 6:20am

Circumstantial evidence against it being Boulding: Does it sound like something he might say?

His faith was no joke to him. He was a serious and sincere Quaker. Non-believers see Christians as smug and complacent, but Christians themselves think the same of their shallow, unthinking, secularist peers.

When grim Lutherans talk about God’s silence, or Methodists about wrestling with God, they see themselves as making a leap of faith, and of trusting in something they can’t demonstrate. That’s the opposite of thinking they have all the answers.

If that’s how it looks from the outside, to a believer like Boulding it’s more like a trial or ordeal or endurance test: “The power of religion in human history has arisen more than anything from its capacity to give identity to its practitioners and to inspire them with behavior which arises out of this perceived identity. In extreme form, this gives rise to the saints and martyrs of all faiths, religious or secular, but it also gives rise to a great deal of quiet heroism, for instance, in jobs, in marriage, in child rearing and in the humdrum tasks of daily life, without which a good deal of the economy might well fall apart.”

Andrew B Brown

Sep 16 2018 at 5:22pm

“Identity” has many connotations and has to do with the ‘self’, so it’s an emotionally charged word.

For some readers, that makes your article difficult to read.

Julien Couvreur

Sep 16 2018 at 11:06pm

This is simply another case of “correlation is not causation”.

We have a number of variables that are correlated, either empirically or more precisely by definition. It does not follow from such relation that the variables are causally related.

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 16 2018 at 11:42pm

Julien Couvreur: Can you please elaborate on what you mean?

Julien Couvreur

Sep 17 2018 at 1:45pm

Let me try to clarify, and also make a correction (the variables are indeed causally related, just not as simply as the equation would suggest).

An accounting identity is a correlation between multiple variables. From such correlation, it does not follow that there is a specific causal relationship between the variables.

For instance:

profits = revenue - costsdoes not imply that any action to increase revenue or to decrease costs will increase profits. The causal relationship is not justrevenue -> profits <- costs(collider diagram whereprofits“listens” to bothrevenueandcosts) as the accounting identity might suggest. Most interventions on upstream variables (which affectrevenueandcosts) will likely affect both.The same goes for national accounting identity and others.

I hope that makes more sense 🙂

Julien Couvreur

Sep 17 2018 at 2:13pm

One small addition to my above reply: the accounting identity

profits = revenue - costsalso does not implyprofits -> revenueorcosts -> revenue.It’s so intuitively obvious in that example that it goes without saying, but for more complex equations it’s possible to make such mistakes.

Craig Walenta

Sep 18 2018 at 6:38pm

“The logical prank comes from begging the question, what is the problem with a trade deficit? It reveals unfair trade practices, answer protectionists. But how does a protectionist determine that trade is unfair? By observing that it results in a trade deficit. The evidence of a trade deficit and of unfair trade is self-referential.”

But as an individual, I really could care less if the macroeconomy is showing a trade deficit. I THINK unfair trade practices would tend to result in imbalance here, but frankly I could care less. But I’m pretty sure I can’t ship to China and that’s not fair and I’m pretty sure Walmart got a property tax abatement while I was stuck paying property tax and I’m pretty sure other economic actors, foreign and domestic, were favored by government entities and I’m pretty sure that’s not fair either. Now if that results in a ‘trade deficit’ — well ok, and if it doesn’t I could care less. But what I do care about is all of those unfair trade practices, which exist irrespective of the trade figures, adds up to a life changing amount of money and I want that money.

Ahmed Fares

Sep 18 2018 at 8:54pm

Pierre,

“When I was in graduate school, I read something to the effect that accounting is like religion”

A Google search on the phrase “accounting is like religion” only gives two hits, both of which link back to you. I don’t think anyone in the history of accounting has ever said that. Unlike religion, there are very few arguments about accounting.

No, I think the phrase you are remembering is “economics is like religion”. This is a phrase I use all the time. (Google gives two million hits on that phrase). Economics is like religion in the sense that like religion, which has branched into so many different denominations, economics has done the same thing.

That and the fact that you can never get two economists to agree about anything.

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 20 2018 at 1:30am

Thanks, Ahmed. I had tried Google, with no more success. It is not impossible that my memories of decades ago are wrong, but I still have hope of finding that quote.

On economists disagreeing, let me quote my latest book (p. 2), where I cite a survey of academic economists by Dan Klein et al.:

T Boyle

Sep 19 2018 at 8:33am

In wartime, countries attempt to weaken each other by undermining each other’s international trade. During WWI and WWII, Germany successfully weakened Britain’s economy with a U-boat campaign that undermined Britain’s ability to trade with North America. In the modern era, the United States routinely interferes with the international trade of other countries (Iran, North Korea, Cuba) as a weapon of “cold war”.

When members of a government interfere with their own country’s international trade, not as a neutral and somewhat unavoidable side effect of having to generate revenues, but for the specific purpose of weakening their own country’s international trade, they are committing an act of economic warfare on their own country – just as if an enemy were to establish a (partial) blockade.

We have a word for people who commit acts of warfare against their own country.

Warren Platts

Sep 19 2018 at 10:42am

Right. And we used B-17s to bomb the crap out of German factories in order to ruin their economy. But nowadays we have politicians and economists who recommend policies that have destroyed 65,000 U.S. factories more effectively than if they were bombed by intercontinental, hypersonic missiles. Traitors indeed.

T Boyle

Sep 19 2018 at 2:08pm

Yes, if one of our politicians destroyed high-value infrastructure – by cyberattack, say – that’s exactly what we’d call them. They’d likely go to jail.

The bomber attacks didn’t target low-value installations; they targeted high-value ones, because they were trying to damage the economy.

But what trade shuts down is low-value activities, that are consuming valuable resources (like labor). The unemployment data show that the labor doesn’t stay unemployed, and it’s not unemployed today. The wage+benefits data show that American labor is highly paid, more so than in the past, because it’s not doing low-value work.

Freeing up our labor force to do higher-value work is not destruction, not harmful to our economy.

To go back to our WWII parallel, Britain wanted North American goods so it didn’t have to divert its workforce to make them. We’re basically doing the same thing today. If you were right, during WWII Germany would have been trying to undermine the UK by paying for North American goods and dumping them in Britain to undermine the British economy, and Britain would have been operating U-boats to close the North Atlantic. Exactly the opposite happened.

Warren Platts

Sep 19 2018 at 3:35pm

That is the theory. The empirical reality is that the workers “released” by the closing of 65,000 manufacturing facilities are NOT doing higher-value work. They–that is the ones that are not part of the 2 million that dropped out of the labor force altogether–mainly moved into the service sector. In round figures, a manufacturing worker puts out about $200K/worker/year. In the service sector, it is more like $50K/worker/year. Thus, despite anecdotal stories about displaced textile workers becoming brain surgeons, most displaced factory workers are now doing LOWER-value work. Therefore, by your definition, that IS destruction, and there is nothing creative about it.

Pierre Lemieux

Sep 20 2018 at 1:20am

For the empirical reality, look at what has been called the “China shock” from 1999 to 2011, when imports from China grew rapidly. Economists have estimated that this disruption destroyed perhaps as many as 2.4 million jobs. But over that same period, 5.6 million net jobs were created in the American economy, that is, over and above the jobs destroyed. More important, the whole economy—real US GDP—grew by 11%, despite the worst recession since the Great Depression. Between the start of NAFTA in 1994 and 2016, real GDP per capita increased by 37% in the US. Real GDP per capita cannot increase if people are producing goods of lower value.

Note also that wages have increased faster in services than in goods-producing industries at least since the Great Recession. See FRED at https://fredblog.stlouisfed.org/2018/09/which-wages-are-really-increasing/#.W6G8xn0Rf_s.facebook. (Remember that two-thirds of what American or residents or other developed countries consume is services.)

Comments are closed.