Economists are occasionally and wrongly accused of being too focused on money, or even of only being concerned about money. Some of the people who make this accusation simply haven’t bothered to study economics themselves. Still, there is one small way that economists might have inadvertently contributed to this perception.

Often when a regulation is proposed mandating things like more generous employee benefits or stricter health and safety standards, a common objection that comes from economists is “implementing this policy will result in lower wages.” To which someone might reply “So what? Money is good but it’s not the only good thing, and standing in the way of safety and benefits in the name of making more money is missing what really matters.”

This reply is fair as far as it goes, but it only works against a misleadingly simplified version of the economist’s objection. A fuller version of the objection is to point out that employee compensation always presents a tradeoff between wages and benefits, and there is no single correct combination that is right for everyone. Some people will happily accept lower benefits in exchange for a bigger paycheck, while others will cheerfully accept a lower paycheck for more generous benefits. Therefore, the best approach would be to maximize the scope for employees and employers to negotiate what mix of wages and benefits works best for their own circumstances and preferences – some employers will offer more wages and lower benefits, some will do the reverse, and even within a single company there can be a wide range made available for what mix of compensation will be offered. Policies that narrow the range of the wage-benefits mix of compensation are creating a deadweight loss.

I’ve taken some pains to try to make this as clear as possible when I touch on this topic, like when I said:

Still, recent posts by David Henderson and Pierre Lemieux on the gender pay gap have made me wonder if sometimes its not the critics of the market who implicitly assume that money is the end-all-be-all of what matters. Both David and Pierre point out that there are significant differences in the kind of work that men and women do, particularly when it comes to work that is physically dangerous and demanding.

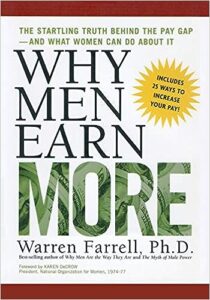

Some time ago, Warren Farrell (who isn’t exactly a rabid right-winger – he was elected to the board of directors of the feminist group the National Organization for Women three times) wrote a book arguing that if you account for a number of different variables like these, and make an apples to apples comparison, the pay gap goes in the opposite direction. That is, women actually make more than men with the same characteristics.

Still, some people push back against this by arguing the reason men and women make such systematically different choices about their careers is because society, implicitly or explicitly, encourages men and women to make those different choices. So, this argument would go, it’s not the case that men are intrinsically more willing to do physically demanding work with a high risk of injury or death than women, or that men are naturally more willing to do work with longer hours that might require frequent relocation than women – it’s because society primes men and women differently. This line of thinking is not new, of course. John Stuart Mill, in his work The Subjection of Women, asserted there were no natural differences between men and women and that “the nature of women is an eminently artificial thing—the result of forced repression in some directions, unnatural stimulation in others.”

I think Mill overstates the case, but let’s ignore that for now. Indeed, let’s go ahead and grant that all of the differences we see in the career choices made by men and women are 100% due differences in social pressure. Should we conclude that this means the gross (that is, unadjusted) pay gap between men and women is a sign that men are systematically advantaged over women?

Well, no – not unless you also harbor the assumption that higher wages are lexically superior to every other consideration. Or, put more bluntly, only if you assume that money is the only thing that matters. For example, women tend to choose careers that offer greater flexibility with their time and require fewer hours. Again, assume this entirely the result of social conditioning. It’s hard to see why this is inherently to the disadvantage of women. One can easily find endless think-pieces on the importance of maintaining a good “work-life balance” and not letting one’s job consume the rest of their life. If men are being socialized into distorting the work-life balance in favor of working longer hours, while women are being socialized into favoring a work-life balance with fewer hours, it’s not at all obvious that the group being pressured into maximizing money while having less time for the everything else in life is getting the better deal. Similarly, if one group is socially conditioned to do dangerous work that pays higher wages, and the other group is socially conditioned to prefer an arrangement with lower wages but much lower risk of being killed or maimed on the job, I think it’s at least arguable that the second group has the better deal.

Acting as if differences in income between groups is evidence that the group with higher income is unfairly better off makes sense only if you assume that maximizing income is all that matters to living a good life. But if money isn’t all that matters, and if there are things in life worth pursing even if they mean getting less money, then this conclusion doesn’t follow.

READER COMMENTS

David Seltzer

Aug 17 2023 at 5:04pm

Kevin: Good stuff. “Similarly, if one group is socially conditioned to do dangerous work that pays higher wages, and the other group is socially conditioned to prefer an arrangement with lower wages but much lower risk of being killed or maimed on the job, I think it’s at least arguable that the second group has the better deal.” From my perspective as a former hedge fund risk manager, I argue that each group gets the best deal. Both are compensated with risk premia relative to each individuals subjective preference for risk. In terms of modern portfolio theory, starting with the risk-free rate, the expected return of a portfolio increases as the risk increases. Any portfolio that fits on the capital market line is the best possible portfolio in terms of risk/reward trade-offs. The capital market line and efficient frontier are, according to Fama’s joint hypothesis problem, difficult to define. CAPM illustrates the concept of returns as proportional to risk for investors.

Dylan

Aug 18 2023 at 8:55am

Good piece. Thought provoking. And certainly fits in with how I’ve viewed work. I had a post here just a day or two ago where I mentioned taking the same job for much less pay, just because of the feeling of flexibility that came with it, even though a lot of that was probably only in my head.

I would say though, from the conversations I’ve had with proponents on the topic, they tend to push back on the mere idea of tradeoffs. That the default should be higher pay and more flexible working arrangements. To some extent, they might be right. The investment banking word I come from seemed to me to be fairly zero sum. There was a culture of overwork that didn’t really seem to improve productivity, but in order to get the deals, you needed to be perceived as working harder than your competitors, which led to a bunch of performative “work” from all sides that wasn’t all that useful. It seemed to me that the real work only took a handful of hours per week, the other 70 or so was making sure all your fonts were matched in that giant Powerpoint deck that no one was going to read.

Much like signaling in education, it seems that we might have reached a stable equilibrium, but not one that is the “best” for the participants in the market.

Henri Hein

Aug 18 2023 at 2:46pm

Dylan,

I have a similar observation, but more from the corporate than the individual perspective. As a software engineer, I’ve had good experiences with the companies I worked for freeing me up to a certain degree to do what they actually pay me to do, that is, develop software. Yet I’ve seen a lot of guff going on in other departments that doesn’t seem to have a good ROI. Of course, some of it is just that as an outsider, I don’t understand everything that is going on, but I’ve definitely seen examples of slim or even negative value activities. One recurring one for me are bloated meetings, both in terms of time and attendance. Another more particular example is a project manager I remember who spent all his time fine-tuning his Project Plans. He spent months perfecting them and seemed very proud of his work, but nobody else cared that much about them. We released products faster than he finished his plans.

Dylan

Aug 19 2023 at 8:48am

I strongly disagreed with his conclusions, but I think David Graeber was onto something with his BS Jobs observation. My last gig was in a big company and my strategy group was reorganized about once a quarter during the year that I was there. You’d work on something for a few weeks, start making what felt like progress, then get reorganized, but not given a new job yet. You’d be told to keep doing what you were doing until they figured out what your new job was going to be. So, for 2-3 months you’d work on something that you knew was going to be thrown in the trash as soon as you were done with it. Then you’d get the new job and repeat the process over again. After a year, my team was laid off as part of yet another reorganization. My co-worker got a job in a completely different division of the same company doing different work. She was at the job about 3 weeks before that group got reorganized and she’s now spent 4 months working very hard to look busy, but having no idea what she’s trying to accomplish. They keep getting told they’ll know something in a “couple of weeks.”

I thought for sure that this must be some weird outlier, but whenever I talk to other people that come from a similar corporate background, I get knowing nods.

Comments are closed.