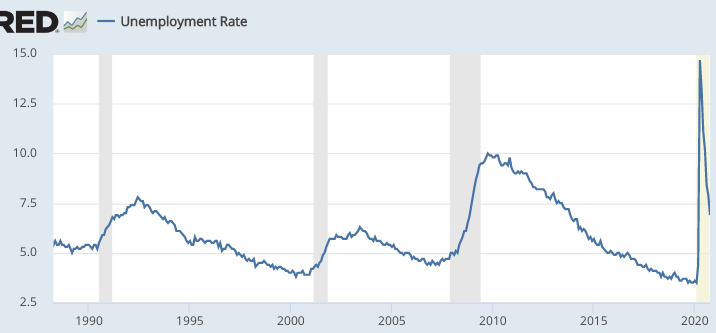

In November 1984, President Reagan said it was “Morning in America”. Good times were back again and the unemployment rate had fallen to 7.2%. He won 49/50 states (including Massachusetts) on the back of a booming economy.

Today, the unemployment rate is 6.9%.

In the Great Recession, it took more than 4 years for unemployment to fall from a peak of 10% to 6.9%. This time it took 6 months (from over 14%).

Lars Christensen might still be correct in his spring prediction that the unemployment rate would fall to 6% by November (these figures were for October.) At the time Lars made the prediction, most experts were highly skeptical.

People will say, “It’s much worse than the unemployment figures show”. Yes, but it’s much worse precisely because it’s a supply shock, not a demand shock.

Supply shocks are really weird. And fiscal stimulus is not going to fix this problem (although it can provided needed relief to jobless workers.) It’s won’t give a job to a parent staying home to take care of kids because schools are closed, and thus isn’t even counted as unemployed.

READER COMMENTS

John Hall

Nov 6 2020 at 1:07pm

One way I’ve been thinking about this is that if the effect is mainly a supply shock would also imply that the aggregate demand is very elastic. This might also be connected in with the flatness of the Philips curve.

However, there might be reasons that supply and demand shocks are not orthogonal and have some correlation, depending on the monetary policy regime [1] . It would be nice to see some empirics on the subject, as applied to the recent period.

[1] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1150581

Scott Sumner

Nov 6 2020 at 11:15pm

I agree that supply and demand shocks are interrelated.

Fred_in_PA

Nov 7 2020 at 12:32pm

As someone who’s a little naive about this, could someone please help my muddled thinking?

What is a demand shock? Or a supply shock?

I’m assuming a demand shock is a situation where the economy goes into the tank because the demand for goods & services suddenly slumps. How narrow can this be and still count? If the demand for movie tickets & bar seating suddenly collapses (people are afraid of the virus), but the other 97% of the economy stays pretty much the same, does this count? I should think any linkage to the supply side would be time-delayed as employers first have to note demand has disappeared and then lay off workers and shut down facilities.

By parallel, I reason that a supply shock is a situation where the economy goes into the tank because the supply of goods & services suddenly slumps. In our current situation, I’m assuming this happens by government lockdown which mandates that producing facilities must close. The obvious link to the demand side will be that, with facilities closed there is no need for workers and hence no paychecks for them to spend.

Do I have it about right, or are there serious lacuna or distortions in this interpretation?

Don Geddis

Nov 7 2020 at 12:59pm

No, that’s not really it.

Classically, “demand” refers to nominal demand. How many dollars are trying to bid for cars, or apartments, or restaurant meals? Aggregate (nominal) demand is generally controlled by the central bank, via monetary policy. A crash in nominal demand (total spending), e.g. in 2008, causes a severe recession and high unemployment. (This is generally believed to be because of sticky wages and debts. In the long run, money is neutral, but in the short run contracts are slow to change and the real economy suffers instead until prices eventually adjust.)

A “supply” shock is a change in the ability of the economy to produce real goods, some raise in the real cost of production. E.g. an asteroid impact, or a war that destroys factories, or a tsunami in Japan, or OPEC artificially restricting oil production.

When you’re talking about people no longer going to movies or bars, that’s actually something very, very unusual. That’s sort of a shock to “real demand”, but there actually isn’t much of a legitimate economic concept of “real demand”. In general, the real demand for goods is essentially infinite. The whole point of economics is to allocate scarce resources, where there isn’t enough supply to meet the actual real-world demand — if the price were zero. There are some very valuable items — such as sunlight, or oxygen — that have sufficient supply at a price of zero that they are not applicable to economic analysis. For everything else (that you analyze in economics), there is always more “real” demand available (at a price of zero) than any conceivable supply.

The current economic recession is not a matter of insufficient money, and increasing nominal demand would not significantly improve it. Hence it is not a “demand-side” recession, but instead a “supply-side” recession.

Dylan

Nov 9 2020 at 12:13pm

Don,

Wanted to thank you for an enlightening post. I had no idea that when people spoke about demand-side recessions they were referring to nominal demand and, for the reasons you mention, the idea always confused me given the unlimited nature of demand.

Garrett

Nov 7 2020 at 7:48pm

Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply are poorly named which leads to a lot of confusion. Think of AD shocks as nominal shocks, or things the central bank do to the future path of the money supply that are unexpected by the public. Think of AS shocks as real shocks, or thinks that happen in the “real world” that affect the economy, such as COVID, Brexit, or the 2011 earthquake that led to the Fukushima accident.

AD shocks can have real effects due to sticky wages and nominal debt contracts. If there’s less money in the economy than expected then there’s less money to pay workers or pay debts, which can lead to unemployment and defaults. AS shocks can have nominal effects when the central bank doesn’t offset them with more or less money.

Scott Sumner

Nov 8 2020 at 12:48pm

Fred, I agree with Garrett. I’d add that when there’s a demand shock, spending tends to fall in almost all sectors. With a supply shock you see more spending in some sectors and much less in others. It’s hard for the economy to quickly reallocate resources from producing cruise ship and restaurant services to building more cars and private boats. That’s a supply problem.

Floccina

Nov 9 2020 at 1:37pm

The USA economy is amazing. Restaurant servers seem to be becoming food deliver people.

Comments are closed.