There’s currently a debate about whether or not the Fed should adopt a policy of “negative interest rates”. But what does that mean? Market interest rates are not a policy; rather they are influenced by various monetary policy choices, perhaps over a long period of time.

Here it will be useful to distinguish between negative market interest rates and negative interest rates on bank deposits at the central bank. Most people ignore that distinction, because (AFAIK) at the moment all the countries that have negative market interest rates also have negative interest rates on excess bank reserves (negative IOER). And yet only negative rates on bank deposits at the Fed can be viewed as an actual “policy”, and even that policy tool is only one component of a broader policy mix. Negative IOER is essentially a tax on excess bank reserves, which are currently assumed to have negative “externalities”.

Negative IOER need not coincide with negative market interest rates. Consider back in 2006, when Treasury bills yielded about 5% interest and the Fed paid a zero percent interest rate on bank reserves. That’s quite a large gap. Thus the interest rate on bank reserves is not necessarily anywhere near to the short-term market interest rate.

Now suppose that in 2006 the Fed had decided to cut the interest rate on excess bank reserves from 0% to negative 0.25%. What would have happened? Actually, almost nothing would have happened to market interest rates. At the time, excess bank reserves were tiny, less than two billion dollars. And 0.25% of that amount is less than $5 million/year, for the entire banking industry. Pocket change. Market interest rates on T-bills would have stayed at around 5%, unless the Fed simultaneously did some other change in policy.

Today, if the Fed were to decide to pay a negative interest rate on excess reserves (and I don’t have strong views either way), then they should do so with the intent of raising long-term bond yields. If the negative IOER policy did not succeed in raising long-term bond yields, then the rest of the policy mix (forward guidance, QE, etc.) would likely have been inadequate. There’s no point of doing negative IOER unless you create expectations of faster NGDP growth, which will generally raise long-term interest rates.

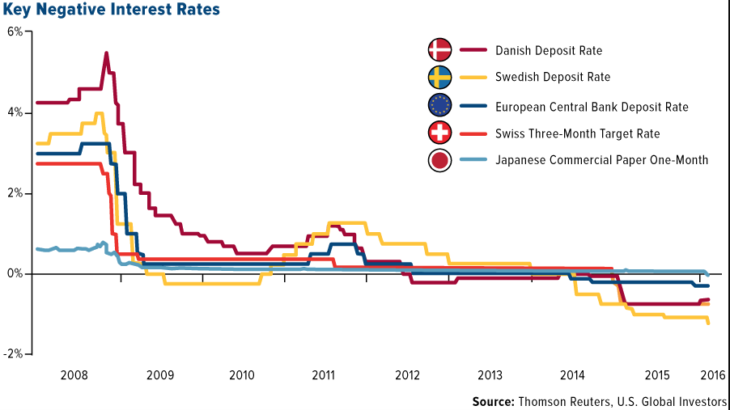

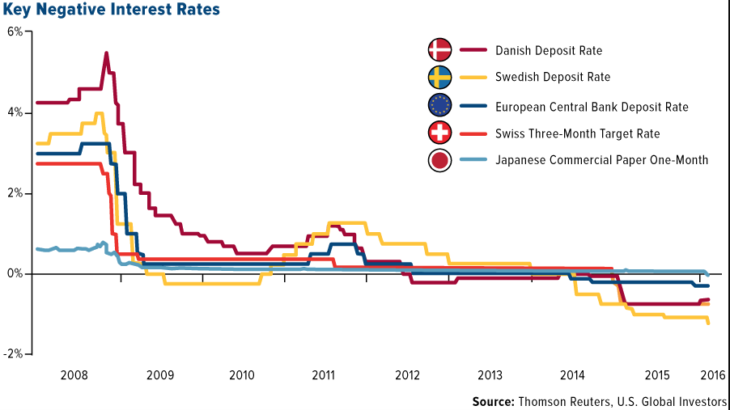

Countries that have negative IOER almost always have excessively tight money, which leads to expectations of very slow growth in NGDP, and this leads to very low or negative long-term bond yields.

Negative IOER is an expansionary policy, considered in isolation. In contrast, negative market interest rates are usually a sign that money has been too tight in the past.

READER COMMENTS

Vaidas Urba

May 15 2020 at 2:54pm

Scott,

you wrote:

”Negative IOER is an expansionary policy, considered in isolation.”

Would it be correct to tell the following story: Positive IOER is an contractionary policy, considered in isolation. In contrast, Bernanke thought in 2008 that the positive IOER combined with credit easing was expansionary.

Scott Sumner

May 15 2020 at 5:52pm

Yes.

Thomas Hutcheson

May 16 2020 at 2:00pm

Negative or positive, whatever it takes to keep NGDP growing at (returning to growth at) 4-5% p.a.

Do you think it is fear of negative interest rates that is preventing the Fed from doing its job: maximum employment (= no unemployment due to inadequate demand and stable prices (PCE inflation = 2%). A TIPS break-even inflation expectation of less than 1% pa over 5 ears is open and shut that it is failing in its price mandate and a pretty strong indication that it is failing to achieve maximum employment.

Scott Sumner

May 17 2020 at 12:58pm

No, I think it’s fear of level targeting.

Pietro

May 16 2020 at 8:16pm

I tried to ask this question at the other blog, but it somehow did not go through.

I’m wondering if our aversion for price-surges, and possibly the laws against such surges, may contribute in keeping inflation low despite the monetary efforts.

Thomas Hutcheson

May 17 2020 at 8:22am

How could that resistance lead to a fall in the TIPS inflation expectations rate? Either the Fed is happy about the fall or they face some self imposed constraint. Maintaining 2% PCE inflation (achieving it actually, as we were never there) is sub optimal, inflation ought to rise when there is a supply shock (that’s the advantage of NGDPL over PL targeting, but what is the explanation for undershooting your target even more?

Scott Sumner

May 17 2020 at 12:59pm

I don’t think so. There were plenty of price surges during the 1970s and early 1980s. Also during the late 1940s and early 1950s.

dede

May 19 2020 at 8:21am

Do you really think that Europeans are as dumb as to set market interest rates below zero?

My view is that the policies do indeed push the actors to accept negative interest rates because they do not have the choice (regulation on insurance companies and banks “compel” them to hold government debt and somehow, they realised in 2011 that the German debt is better than the Greek one, even if it serves a negative interest rate).

Ergo, there could indeed be a policy of negative interest rates in the US and, if I am right, it would not be good on that side of the Atlantic either (in Europe, it clearly sent the message that the future was so doomed that nobody has dared to invest over the last ten years)

Spencer Hall

May 28 2020 at 12:02pm

BuB “Money is fungible”…“One dollar is like any other”, pg. 357 in “The Courage to Act”

No, savings have ≥ 1 dollar economic impact. Money has ≤ 1 dollar.

The use of savings products raises the real rate of interest. The use of money products lowers the real rate of interest. Money products have a negative economic multiplier. Savings products have a positive economic multiplier.

Prima facie evidence:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LTIIT

Comments are closed.