A Texas civil court found that Alex Jones defamed the parents of a young child killed in the 2012 Sandy Hook massacre. He was ordered to pay $49 million in damages, including punitive damages.

Among others, Jones had been claiming that the massacre was a hoax, a government-staged fake shooting. Let’s consider some social consequences of the sort of conspiracy theorists that Jones represents—what we might call, at a very elementary level, the political economy of the Alex-Joneses. What I say below should not be interpreted as an argument in favor of defamation laws, nor as an argument against economic progress.

For nearly all the history of mankind, an individual handicapped by social illiteracy or limited cognitive abilities could only earn his keep by, at best, being a bottom-level manual worker (which is of course honorable) or a beggar or, at worst, a peddler of snake oil or a petty criminal. Economic progress and the reduction of communication costs have greatly increased the capability of such individuals to act and have an influence in the social world.

The reduction of communication costs has extraordinarily expanded the availability of information. Much of it is available online and is formally free of charge. But the cost of discriminating among information bits has not decreased in the same proportion. One still needs some research time and previously accumulated knowledge to determine where the truth lies in pieces of information broadcasted by, say, Alex Jones, Paul Krugman, the Census Bureau, or the Wall Street Journal. The mere fact that there is quantitatively more available information means that, ceteris paribus, the cost of sifting through it has increased.

At virtually no cost to them, conspiracy theorists throw at their audience a swarm of troubling or intriguing little facts (see what was the most popular conspiracy video on Sandy Hook), most of which are false or tendentiously interpreted. Most if not all of these little facts could be checked, albeit often at high cost (travel, for example), and there is always another ad hoc explanation that can be invoked to save the conspiracy. Anybody with a connection to the internet and a cheap smartphone can access that. According to some estimates, one fourth of Americans believed that Sandy Hook, where 20 young children and 6 adults were killed, was a government-organized hoax.

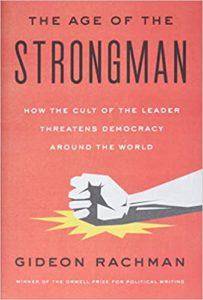

Such propaganda relies on the technique of the “firehose of falsehoods” mentioned by Financial Times columnist Gideon Rachman in his recent book The Age of the Strongman (Other Press, 2022); I am reviewing this book in the Fall issue of Regulation, forthcoming next month). Rachman writes:

Vladimir Putin and his propagandists established the technique of a “firehose of falsehoods” as a fundamental political tool. The idea is to throw out so many different conspiracy theories and “alternative facts” (to use the phrase of Trump’s aide, Kellyanne Conway) that the truth simply becomes one version of events among many.

Not only do conspiracy theorists incur low costs, but they can make handsome profits if, like Jones, they have gullible followers anxious to buy physical snake oil. When I visited Jones’s Infowars site two days ago, the special deal was a “combo pack” of two bottles, “Survival Shield X2” and “Super Male Vitality,” at 40% off. For such ventures, the cost of marketing has gone down with the cost of communications—although, on the other hand, competition has become fiercer.

Besides the spreading of implausible falsehoods, another consequence of the Alex-Joneses of this world is that they compromise serious ideas by claiming to be their defenders. Alex Jones and his ilk have given Judas kisses to a few libertarian (and classical liberal) causes. His company is called “Free Speech Systems.” He claimed that the Sandy Hook hoax was organized by dark government forces because they want “to get our guns.”

Some people have such strong opinions that they are unable to imagine they could be false. If their opinions are obviously and necessarily true, anything consistent with them or implied by them might have happened, including conspiracies to suppress them. “Might have happened”? If we ignore logic, they must have happened. From there, it is not too difficult to ferret out strange factoids to support the conspiracy or to invent facts that must have occurred.

I have explained in other posts how economic analysis strongly suggests that the typical “conspiracy theory” is invalid. See my “Epistemology, Economics, and Conspiracies” (EconLog, December 3, 2020) and its two links to previous posts of mine; and also “A Disreputable Fringe” (EconLog, August 2018), partly about Alex Jones. Of course, some low-level conspiracies with little risk involved happen all the time and we must keep a critical mind.

The solution cannot be to silence the Alex-Joneses, because distinguishing brilliant eccentrics and innovators from fools cannot be trusted to anybody. Only a free market in ideas can ultimately separate the wheat from the chaff. Trusting political authorities to separate falsehoods and true statements may turn out into trusting fools. (In America and elsewhere, we have had some recent experience with that.)

The minimum knowledge necessary to discern obvious falsehoods puts in sharp focus the classical-liberal argument that some level of schooling is necessary in a liberal or democratic society. Friedrich Hayek, for example, wrote (in his 1976 “The Mirage of Social Justice,” Vol 2 of Law, Legislation, and Liberty in the new Jeremy Shearmur edition, p. 285):

There is also much to be said in favour of the government providing on an equal basis the means for the schooling of minors who are not yet fully responsible citizens, even though there are grave doubts whether we ought to allow government to administer them.

Education helps to acquire the ability to recognize what one does not know and to learn some intellectual humility—or at least we can hope so. To know what it is that you don’t know is a tricky department of knowledge. One aspect of the complex problem was described by James Buchanan (pp. 16-17): “the person who qualifies for membership in the stylized order of classical liberalism,” he believes, must have

either an understanding of simple principles [of social interaction] or a willingness to defer to others who do understand.

READER COMMENTS

Scott Sumner

Aug 21 2022 at 1:58pm

“The solution cannot be to silence the Alex-Joneses, because distinguishing brilliant eccentrics and innovators from fools cannot be trusted to anybody.”

Are you suggesting that someone is trying to silence Alex Jones?

Dylan

Aug 21 2022 at 3:25pm

I don’t get that Pierre is suggesting that, rather than preemptively dismissing what is often a knee-jerk reaction to the existence of crackpots.

Pierre Lemieux

Aug 21 2022 at 3:52pm

Scott: I had nobody in mind, but we can get a sense that many people would like to silence him from the fact that he was deplatformed by Twitter, FB, and YouTube. Of course, these private decisions are not the same as removing his First Amendment protection, an important distinction that must be kept in mind. But then, note that the function of defamation laws has often been to prevent controversial or anti-establishment speech; consider the British defamation laws, which protect deep-pocketed celebrities, and even Trump’s 2016 electoral wishful idea that these laws be tightened in America. And some opinion polls suggest that Americans only like the First Amendment for their tribes: see the troubling pool results I reported in my post “Many Americans Don’t Like Free Speech.”

Of course, anybody should be morally disgusted that Jones could harass parents who had lost children instead of living an honorable life as a burger flipper.

Scott Sumner

Aug 21 2022 at 5:58pm

That makes things a clearer. I guess I thought your post was a bit confusing, as you started off talking about the defamation suit, and then switched to his crackpot views on government conspiracies, which is a different issue.

But yes, you could say that private firms are trying to silence him. My point is that the defamation suit was not about his political views.

Pierre Lemieux

Aug 21 2022 at 11:12pm

Scott: I could have been clearer. The defamation suit is not about his political views. As we see in the UK (and in Trump intuitions on that matter), however, antidefamation laws can easily be used to silence non-crazy people revealing things that the establishment (or the government) does not want revealed. Perhaps I should have mentioned my general doubts about antidefamation laws later in the post.

Craig

Aug 22 2022 at 8:19am

“The defamation suit is not about his political views.”

They’re intertwined, I mean AJ’s schtick is that the government wants to take away your 2nd Amendment rights and the mode is staging the likes of Sandy Hook and that it is otherwise affirmatively creating the pretext to strip away the 2nd Amendment.

“however, antidefamation laws can easily be used to silence non-crazy people revealing things that the establishment (or the government) does not want revealed.”

Of course if its not revealed, its not defamatory, the nuance here, Professor is that the existence of defamation laws means some might fear they will be used as a ‘sword’ instead of as a ‘shield’ and it will have a ‘chilling’ effect on speech, ie people will choose not to reveal things out of fear of being sued for defamation — even in circumstances where they know they can ultimately prevail because they know its the ‘truth’ because of the potentially prohibitive cost of litigating, generally.

Mark Brady

Aug 21 2022 at 2:16pm

Pierre writes, “For nearly all the history of mankind, an individual handicapped by social illiteracy or limited cognitive abilities could only earn his keep by, at best, being a bottom-level manual worker (which is of course honorable) or a beggar or, at worst, a peddler of snake oil or a petty criminal.”

I prefer, and commend for your attention, Adam Smith’s perspective, viz., “The difference of natural talents in different men, is, in reality, much less than we are aware of; and the very different genius which appears to distinguish men of different professions, when grown up to maturity, is not upon many occasions so much the cause, as the effect of the division of labour. The difference between the most dissimilar characters, between a philosopher and a common street porter, for example, seems to arise not so much from nature, as from habit, custom, and education.”

–Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), vol. 1, Book I, Ch. II, Of the Principle which gives occasion to the Division of Labour; emphasis in original.

Pierre Lemieux

Aug 21 2022 at 3:20pm

That’s of course a good point, Mark. Smith appears to be, on natural equality, an extreme Enlightenment thinker, but he also, like any Enlightenment thinker, mentions the importance of education. This is consistent with Hayek’s view. I tried to make it consistent with Buchanan’s view by writing, in my review of the latter’s Why I, Too, Am Not a Conservative:

Do you think that this reconciliation between Buchanan (or Hayek) and Smith works? It is true that it does not work perfectly if there exist some biologically-determined “limited cognitive abilities,” and this is why I mentioned this possibility. In other words, could Alex Jones, if he had gone to the same schools and have met the same general conditions of life as you or I, have studied economics and now be discussing with us the political economy of the Alex-Joneses?

David Seltzer

Aug 21 2022 at 5:19pm

Pierre: “The minimum knowledge necessary to discern obvious falsehoods puts in sharp focus the classical-liberal argument that some level of schooling is necessary in a liberal or democratic society.” May I add: if the marginal societal benefit exceeds the marginal cost to tax payers. National average cost per student in 2020 was about $16,000. National average graduation rate was nearly 86%. Of that 86% credentialed, how many learned to think critically, remain skeptical and curious when hearing the proffered conspiracy conjectures of the Alex-Joneses of the world? I’m rather pessimistic.

Pierre Lemieux

Aug 21 2022 at 10:58pm

David: Your concern is valid. This is why I added “or at least we can hope so.”

Mactoul

Aug 21 2022 at 10:29pm

Education is hardly a panacea. The educated and over-educated believe in scientific nonsense and conspiracies not less than uneducated and cognitively challenged. See the craze for transgenderism among the educated.

Pierre Lemieux

Aug 21 2022 at 11:03pm

Mactoul: Like David, you are right: education is not a panacea. Its usefulness depends on its quality. In an age of obscurantism, it will likely follow. Note the qualification added by Hayek.

Jose Pablo

Aug 22 2022 at 7:47pm

If it is useful for over-educated people to believe (and to make others believe) in nonsenses they will do it.

Incentives matter.

Your example on trasgenderism (or wokeness in a more general sense) in academia (I read you refering to them) is a great example of that.

Rebes

Aug 21 2022 at 11:46pm

By all means, let crackpots spread their ideas. But Alex Jones is in a different category. There is nothing more devastating to a parent than to see their child get murdered, and he accused those parents of lying, which in turn encouraged his followers to harass those parents. He has to be held accountable for the externalities of his lies.

It’s worth reading about Julius Streicher. He didn’t participate in the Holocaust directly, all he did was publish a paper that constantly propagated the extermination of all Jews. Free market in ideas?

Jose Pablo

Aug 22 2022 at 7:00pm

But falsehoods and misinformation have been part of humanity since the begining of time, haven’t they?

The frontier between “falsehoods and misinformation” and “formal religion” (or Greek mythology), for instance, is “blurred” to say the least. And look at communist or nazist “propaganda”.

And “the reduction of communication costs” has affected this human tendency (to produce and consume falsehoods and misinformation on an epic scale) the same way that has affected pornography (another old friend of humankind).

Not sure what is my point here. That the epidemic of falsehoods and misinformation (personalized in Alex Jones) is the same old … only on steroids. And “putting things on steroids” is something internet does to everything (blogs, sales, dating, sharing data, working on teams ….)

Same old, same old

Jose Pablo

Aug 22 2022 at 7:41pm

“Only a free market in ideas can ultimately separate the wheat from the chaff. “

That’s interesting. The “market of ideas” does not seem to have done a wonderful job historically when it comes to eradicate falsehoods and misinformation.

But why should it? The market of ideas will, most likely, separate the ideas that produce an increase in utility to certain people (the “right kind” of people or the right number or both), whether true or false ideas, from the ones that does not.

After all, “the truth” is greatly overvalued when “usefulness” is the objective function.

Citing Huemer (from your own post in 2021):

Our natural tendency is to try to advance our own interests or the interests of the group we identify with, and we tend to treat intellectual issues as a proxy battleground for that endeavor. Again, we don’t expressly decide to do this; we do it automatically unless we are making a concerted, conscious effort not to. And naturally, when we do this, we form all sorts of false beliefs, because reality does not adjust itself to whatever is convenient for our particular social faction.

So, “markets in ideas”, in which “people with natural tendecies” participate, will, very likely, promote “all sorts of false beliefs (that are) convenient for our particular social faction”.

Smart people has been very sucesful exploiting this since the begining of humandkind.

Pierre Lemieux

Aug 23 2022 at 10:58am

Jose: You write:

The market of ideas has only been permitted to work for small stretches of time on part of the earth during the past 500,000 years. And approaching the truth takes time. And, as Huemer himself argues, there has been intellectual progress, albeit with retreats, between the hunter-gatherers or the Egyptians and today.

Jose Pablo

Aug 23 2022 at 2:11pm

That’s fair Pierre. You cannot expect the market of ideas to work where it does not exist (although goods and services markets do achieve something even when imperfect)

Let’s say that “1st amendment bonded modern democracies” are the closest we (human beings) can get to the “market of ideas” that “promote the truth”. That means we have had a “market of ideas” as good as we can get for the last 230 years in the US.

The lack of a proper measure of the prevalence of falsehood and misinformation in a given society makes any time comparison very difficult but it seems (as per your own post) that falsehoods and missinformation are still quite prevalent in the US. One would be tempted to believe that increasingly so in the last years. You can even argue that a Champion of Falsehoods and Misinformation was chosen as President “almost” twice and could be chosen again in the future (he definitely captures the imagination, to say the least, of a party representing around half of the citizens of the country)

230 years of the market of ideas works for getting this result? … I don’t know, “approaching the truth takes time” looks like an understatement.

Pierre Lemieux

Aug 23 2022 at 4:47pm

Jose: Nothing is perfect. But your 230 years are rather at most 154 years as the count for the states starts with the 14th (“incorporation”) Amendment. Even in the case of the federal government, a strict jurisprudence and interpretation of the 1st amendment only developed with time. It’s probably, I guess, only in the 1950s or 1960s that we can say that the 1st Amendment was seriously in force–except for social media companies and a few other fears of Leviathan! From 1779 to about 50 years ago, it thus seem paradoxically, freedom of speech was better protected in England (and perhaps, in practice, at certain points of time, in other European countries and Canada).

TMC

Aug 23 2022 at 10:33am

I had no idea that many people believe Sand Hooky conspiracies. FYI though, “The idea is to throw out so many different conspiracy theories and “alternative facts””…

“Alternative facts” is a legal term that means a different set of true facts that tell a different story. Say if the police were looking for you believing you were involved with a crime. Your plates were scanned by a nearby red light camera. Alternative facts would be a credit card receipt from a distant place at the same time, or your cell phone pinging a remote tower. Al the facts are true, they just tell different stories.

Pierre Lemieux

Aug 23 2022 at 11:42am

TMC: Interesting point on “alternative facts.” But is it standard legal terminology? Do you have a citation? In an article by S.I. Strong in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review Online, “alternative facts” are characterized by cognitive biases. Another way to conceive of them would be as incoherent partial subsets of facts (your example) related to a hypothesis (“I am guilty” or “I am innocent”), subsets that cannot falsify the hypothesis. In all those cases, we have what we can simply call an incorrect interpretation of an incomplete subset of facts.

TMC

Aug 23 2022 at 4:08pm

Here’s one: https://ndaa.org/wp-content/uploads/Cross-Exam_for_Prosecutors_Mongraph.pdf

I searched for this right after Kellyanne Conway used the term and found plenty enough examples, but today the internet is too polluted with so many bad faith definitions it isn’t easy to find these.

Craig

Aug 24 2022 at 9:46am

“Alternative facts” is a legal term that means a different set of true facts that tell a different story. Say if the police were looking for you believing you were involved with a crime. Your plates were scanned by a nearby red light camera. Alternative facts would be a credit card receipt from a distant place at the same time, or your cell phone pinging a remote tower. Al the facts are true, they just tell different stories.

I don’t think of the term ‘alternative facts’ as being a term with a black letter law definition. Your description of what looks to be difficult to reconcile facts would typically be part of some kind of alibi defense, right? Ultimately the fact is we can only be in one place at one time, so there needs to be an explanation. Nevertheless as you suggest if I listen to those facts I can draw one reasonable inference which is that you were driving the car and not elsewhere. The Professor can hear those facts and draw a different inference that the person was at the phone. One might hear something along the lines of, “Its the prosecution’s theory that so and so was driving the car which slammed into a pedestrian, but defense counsel has put up an alternative theory that somebody else was driving the car and he was actually up in the mountains texting his wife”

As I see the term typically used today it can be used in wildly different contexts, even at times as a sort of insult. Its context is derived from the speaker and I’d suggest this divisive Zeitgeist which seems to surround public discourse.

Craig

Aug 24 2022 at 10:12am

“I had no idea that many people believe Sand Hooky conspiracies.”

Belief in conspiracy theories is rooted in distrust of government.

Let’s look back at a statement by Madeline Albright. She was asked at one point if she thought that US sanctions at Iraq were justified even though the sanctions had killed one million Iraqi children. Albright’s response is that it was ‘worth it’ [the assertion that 1 million children were killed by the sanctions is incidental because ultimately that factual assertion wasn’t disputed by Albright, ie its about her moral calculus about the sanctions v 1mn deaths, a fact assumed to be true”

Right there is evidence that the government will engage in relatively horrid behavior to pursue policy objectives the government determines to be legitimate.

If I were to ask you a question, “Do you think the government will pack the court to get different decisions from the Supreme Court to redefine 2nd Amendment rights?”

Maybe you believe they will do it, maybe not, but the concept is definitely out there and so yes, there are people who believe that the government sees eroding the 2nd Amendment as a legitimate policy objective. Further to that there are those who believe that the government will engage in pretextual conduct to justify eroding those rights.

Alex Jones has tapped into that and he is trying to profit off of it in ways that I don’t even think he believes to be true. He knows there are people out there who believe the government will engage in horrid behavior to pursue policy objectives the government determines to be legitimate because they absolutely have done that.

9/11 conspiracy theories are rooted in a similar thing stemming back to something like the Gulf of Tonkin. There are people who believe the government will create a pretext to go to war.

The Professor notes: ““alternative facts” are characterized by cognitive biases.” — My cognitive bias would be taxes so to me the lying vampire class of illegitimate parasites will do or say anything to make a moral claim to more than half my income by direct taxation or inflation rooted in the truth that they did that to me in NJ. There’s no real penetrating that either.

Comments are closed.