There are many arguments against government regulation of price and quantity. In competitive markets, regulation moves equilibrium away from the most efficient outcome. Regulation can produce black markets. There are administrative costs associated with regulation.

One often overlooked consequence of regulation is that it adds to the complexity of decision-making. Thus government regulation tends to favor the better informed members of the community, over those who are less well informed.

Although I have a PhD in economics, I don’t believe that I am anywhere near well informed enough to deal with government regulation:

1. The tax code is too complex for me. I’ve given up and farmed the job out to an expensive tax accountant.

2. The health insurance system (which is almost completely a product of government regulation) is too complex for me to navigate. I spend far too much of my life dealing with its complexities, and still fall well short of understanding the system.

There are many other areas of life where being well informed helps one to deal with the complexity of regulation. Big companies have an easier time complying with complex regulations than small companies. Occupational licensing laws favor those with more formal education. Our welfare state favors those who understand the complexities involved in applying for benefits. Expertise in taxes favors those who wish to avoid estate taxes, or those who wish to avoid losing wealth to the government after signing up for Medicaid. Our immigration system is highly complex and difficult to navigate.

In the past few days I came across two stories that nicely illustrate this concept. One story discusses applying for Global Entry. Apparently it is extremely difficult to schedule the required interview. (I am currently attempting to do so.) Thus well-informed people will hire a firm to search out an available spot. I won’t say this never occurs in the private sector (concert tickets can be hard to get) but with government offices a long wait is more the norm than the exception. Ever been to the DMV? The Social Security Administration?

Another example was discussed in a recent Reason magazine article:

Legal restrictions on pseudoephedrine sales, in short, gave us reformulated products, including pseudo-Sudafed, that not only do not work as well but apparently do not work at all, as you may have discovered after trying them. But at least those ineffective products are easy to buy.

Legal restrictions on pseudoephedrine, by contrast, took it off the shelves and put it behind the pharmacy counter, whence it can be retrieved only under certain conditions.

Readers might be thinking, “What’s the problem, you could just ask the pharmacist for the better product.” Here’s the problem. A solution that is obvious to one person might be not at all obvious to another. I spend an enormous amount of time on monetary economics. When I have free time I watch films and read books. Yes, I could have spent my time researching how pharmacies dispense drugs, and then the regulation would not have harmed me. But I bet I’m not the only consumer who naively assumed that the cold medicines that one found on the aisle in a pharmacy were effective in reducing the symptoms of a cold.

There’s an almost infinite amount of time we could spend making our choices more effective. I could spend hours looking into how to change the oil in my car, or how to get the best deal when buying airline tickets, or how to save money on my taxes. But my time is valuable, so I choose to spend it in other ways.

When the government designs its tax laws and regulations, it seems as though almost no weight is put on the way in which the rules favor those who are better informed. I have two problems with complex regulations:

1. They favor the cognitive elite (as well as big businesses that can hire people to navigate the regulations.)

2. They incentivize people to become well informed about facts with no social utility.

The first problem relates to equity, the second to efficiency.

Regulation creates a shortage of painkillers. Who gets painkillers in that environment? Those who are smarter and more well connected. Regulation creates a shortage of kidneys for transplant. Who gets kidneys in that environment? Those who are smarter and more well connected. The safety net doesn’t have enough money for everyone who is needy. Who benefits from government programs? People smart and well connected enough to navigate through all of the paperwork. (I.e., not the homeless.) Who has an easier time navigating the regulatory gauntlet to build new houses? The big builders. There are many more such examples.

Progressives tend to favor big government, thinking it will help those on the bottom of society. Sometimes it does. But big government also creates a system that favors those who are skilled at navigating its complexity—the economic and cognitive elite.

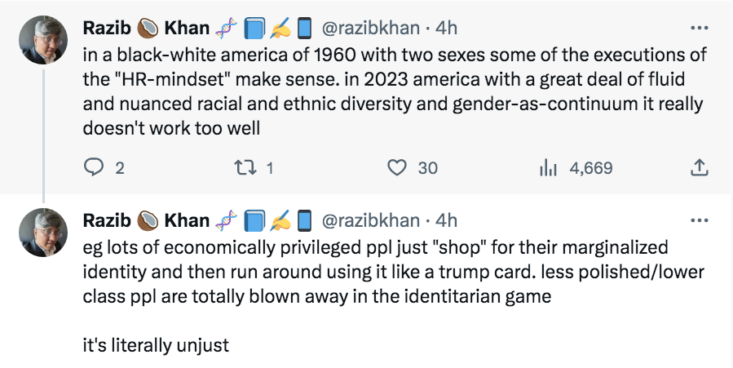

PS. These Razib Khan tweets makes a related point:

READER COMMENTS

john hare

Oct 8 2023 at 3:16pm

That last tweet by Razib Khan reminds me of an ex friend. I had known him for about 40 years and he was always looking for the “free ride’. Mostly amusing and didn’t bother me. Then one day he mentioned that doing geneology research he had found out that he had an Indian ancestor in the late 19th century. So he had applied for an “Indian check”. Haven’t been back to his house since. Probably petty of me how disturbed I was.

Philo

Oct 9 2023 at 11:58pm

He is just playing the identitarian game that the government rewards us all for playing–a game that deserves to be gamed!

john hare

Oct 10 2023 at 4:26am

I also have a problem with other people that steal. Including those that deliberately do things that put them in the “need” so they can get government money.

Dylan

Oct 8 2023 at 4:05pm

Excellent piece and I think the point about the folks who bare most of the burden of regulation is supremely underestimated by almost everyone.

I want to pick on one part though

We’ve seen a number of arguments on Econlib about getting the FDA out of the efficacy business and letting drugs be sold after passing some basic safety standards. It seems to me we would get a lot more cases of ineffective drugs being sold and no one would be in a good position to evaluate what works. How much pseudo-Sudafed do you think was sold over the last 17 years? How much do you think is still being sold today?

Scott Sumner

Oct 9 2023 at 1:13am

In one way I agree. But there’s also an argument that we’d get more effective drugs. I recall having a severe toothache on Friday night and couldn’t get to the dentist until the following Monday. Imagine being able to go to the drugstore and buy a strong narcotic!

Dylan

Oct 9 2023 at 9:36am

Sure, but that is a different issue. That’s moving prescription medication that has already been proven effective* to OTC status. If you’re talking instead about pain medication that hasn’t been tested yet, well that I think would be pretty unhelpful. For a short period in the late 00s, I’d come across a small biotech trying a new approach to pain about once a week it seemed. They universally failed in later stage trials, almost always because the approach didn’t work despite promising early results.

*I actually found out last year that opiates don’t seem to have much effect on me. After an accident I was given morphine at the hospital and oxy to take home. Neither made a dent in the pain as much as plain old tylenol did.

steve

Oct 9 2023 at 10:20am

We have an essentially unregulated sector in the supplements market. They largely dont work. We also have an unregulated “home remedy” market. They dont work wither and are sometimes harmful, like the folk remedies that include mercury.

I could be wrong. If anyone here has had their penis grow another 6 inches after taking the advertised supplements feel free to let us all know.

Steve

Dylan

Oct 9 2023 at 12:11pm

Don’t even get me started on the supplements and home remedy market. Last weekend I went to the drug store looking for medication for my wife, who had developed a stye. Finally find the right section, but it is behind a locked shelf, so I have to go chase down an employee to unlock it, only after which I can see that in a small label on the back it says homeopathic.

From a freedom perspective, I’m all in favor of people being able to buy what they want, including snake oil if they want it. But, it sure doesn’t speak well of the ability of the market to distinguish between what works and what doesn’t.

Chern

Oct 10 2023 at 11:54am

Try examine.com. Many supplements are effective. My children use some for anxiety with a lot of studies behind them and they are highly effective. I am glad we don’t have to use pharmaceuticals.

Jeremy Goodridge

Oct 8 2023 at 4:43pm

When I was young, I used Sudafed all the time and it worked great. The effect was strong. Hard to believe it was all placebo. I wonder whether sone drugs work on a minority of people and the FDA can’t pick that up.

And why shouldn’t people get to buy drugs that aren’t approved by the FDA? Are we children? Don’t I have a right over my own body?

My view is that the FDA should be able to put a mark on drug that it’s approved or not, but consumers should be free to ignore that mark.

robc

Oct 9 2023 at 9:20am

Sudafed works. Its the fake Sudafed that Scott says doesn’t work.

Peter

Oct 9 2023 at 2:53pm

Jeremy: What you are missing is the non-OTC Sudafed, which is still sold and labeled as Sudafed, hasn’t contained the active ingredient which made Sudafed work and people expected for about two decades now. You also see this problem with Benadryl, sore throat medicine, and cough syrup. I.e. same name but different formulation, would be fraud if wasn’t government mandated.

And if you want to hear a really asinine story, here in Hawaii they won’t sell you NyQuil unless you are 21 or over. Likewise alcohol free beer.

Kevin

Oct 8 2023 at 6:48pm

There is already a system in place, irrespective of what the FDA does, that polices The efficacy of drugs. That’s why off-label prescribing happens all the time. Mounjaro was approved last year as an anti diabetic drug. It has been prescribed as a weight loss drug more or less ever since, even though it isn’t approved for that indication yet. The FDA approved Aduhelm back in 2021 to treat Alzheimer’s disease — it ended up being one of the biggest flops in the history of the biotechnology industry, despite the dire and massive need for AD medicines.

That’s largely because even though the FDA approved it, physicians and hospital systems explicitly said they wouldn’t prescribe it, which strongly suggests these people and institutions have their own mechanisms for deciding whether drugs are effective, and of course they do. Large biotech companies typically make the data on their clinical trials public. There are experts out there who can evaluate it. The FDA itself sometimes convenes panels of independent experts for extra help.

I am sure there would be more ineffective drugs sold if not for the FDA, but there would also be more drugs overall, and the approval process would be substantially faster. I am not sure what the net effect is. All the middlemen in the healthcare sector that pay for or sell drugs (third-party payers, pharmacies, physicians) have an incentive to make sure these drugs are safe and effective. If the FDA gets out of the efficacy business, that creates a huge and potentially highly lucrative market for a private company to hire experts to offer their expert advice to these middlemen and to consumers.

robc

Oct 9 2023 at 9:22am

Every study I have seen says that delays in good drugs reaching the market kills more people than are saved by preventing bad drugs from being sold.

steve

Oct 9 2023 at 10:29am

This is what happens when people who dont routinely study and write about health care speculate about it. A new drug is approved and then like magic everyone uses it. The reality is that if a drug comes out with a lack of studies behind it even if approved it will be slow to be adopted, barring the truly miraculous drugs, which are rare. Even doctors know about the replication problem and we are reluctant to start using a new drug until there is broader experience.

So the people willing to experiment try the new drugs and more conservative people wait. So in the idealized market where new drugs automatically go out to everyone maybe delay kills more people. In the real world I dont know if that’s true.

Steve

robc

Oct 9 2023 at 11:12am

Its been a long, long time since I looked at the studies, but IIRC, just one of those miraculous drugs was more than enough to outweight the deaths from bad drugs.

I remember it being an order of magnitudes difference, so even if adoption sloped up over the decade of delay, it would have delivered the results.

Like I said, its been a long time, but I think that is a bad assumption on your part. As I think it was someone who spent their career writing and studying health care.

Kevin

Oct 9 2023 at 11:26am

In other words, doctors don’t simply blindly follow the lead of the agency whose job it is to say whether drugs are safe and effective, which was precisely my point. (Also, I do write about the healthcare sector).

And this point somewhat undermines the rationale for there being an FDA.

steve

Oct 10 2023 at 1:11am

?? Dont really see that. The FDA generally asks for the kind of studies we want to see. They are responding to pressure in some cases so when we see fewer studies we are more careful.

Steve

jdgalt

Oct 8 2023 at 10:56pm

In examining the efficiency of regulation, the author assumes that regulations are enacted for the purposes they say they serve, such as protecting the public. They do no such thing. Regulations are really written by lobbyists for the purpose of making it harder and more expensive to operate a business in the industry supposedly being regulated. Thus (for example) regulations of pharmacies are about protecting existing pharmacies, especially the largest chains, from competition. To that end, the small number of people who know enough to navigate the regulated environment well is not a bug, but a feature.

Never assume that politicians want to help you. They couldn’t care less about you. They help the people who pay them the most.

Scott Sumner

Oct 9 2023 at 4:13pm

“the author assumes that regulations are enacted for the purposes they say they serve, such as protecting the public.”

Which author? Certainly not me.

Richard Fulmer

Oct 9 2023 at 10:16am

Has anyone done a study to determine what percentage of federal regulations (regardless of their stated intent) work to the benefit of special interests rather than to that of the general public?

robc

Oct 9 2023 at 11:15am

The closest I know of is Ronald Coase saying that no new regulations worked at all.

I think this was basically a law of diminishing returns situation, in that we have so many regulations that we were to the point that any new regulation, no matter how good it would have been on its own, had a negative impact in combination with every other regulation.

Mark Brophy

Oct 9 2023 at 5:55pm

I can’t imagine any regulation working for the public rather than a special interest.

Walter Boggs

Oct 9 2023 at 7:48pm

One reason is that the special interest often helps to write the regulations.

Scott Sumner

Oct 9 2023 at 11:47am

Everyone, It’s useful to differentiate between two issues:

Should the FDA approve drugs that are safe and effective?

Should it be legal to buy drugs that are not FDA approved?

Those are two radically different issues. I could imagine a world where the FDA approves Tylenol for toothaches, doesn’t approve heroin, but doesn’t ban people from using heroin if Tylenol doesn’t work for them.

Indeed, I would prefer that world.

Dylan

Oct 9 2023 at 12:25pm

Agree that it is good to differentiate those two issues. I too favor the world where it is legal to buy drugs that are not FDA approved as long as the FDA (or something like it) still exists to test and evaluate that drugs are effective and safe (which is always relative to what they are trying to treat).

I’m not 100% certain we’d still have an FDA equivalent in a world where drug companies could skip that step and go straight to market. The incentives might align in such a way that no one could afford to spend a billion dollars to run the trials needed to prove something works. That’s not an argument against it, just suggesting caution. My experience with healthcare is that things are so intertwined and interdependent, that making a change to one part of the system can have pretty unexpected results somewhere far away from the change you make.

robc

Oct 9 2023 at 2:11pm

I would think something like Underwriter’s Laboratory would develop for drugs in a non-FDA world.

Drug companies won’t want to get sued. Their insurers will want some sort of testing before products go on the market.

steve

Oct 10 2023 at 1:09am

If you pay all of the costs for the follow on effects for choosing a drug that doesnt work or harms you then I would be OK with that. If you want to knowingly take risks then also take the financial risk. Actually, since you will show up in my ICU I would prefer that I be allowed to charge you extra as an aggravation charge.

Steve

vince

Oct 9 2023 at 6:39pm

Yes, depending who pays for negative consequences.

Dale Doback

Oct 9 2023 at 1:18pm

While I agree with the sentiment and the examples, I believe non-elites can benefit from complex regulation. For example, building codes for a house or safety testing for a vehicle. Not having to navigate these complexities was likely a huge benefit to buying a house or car (for all parties).

My issue is not regulations per se but the enforcement mechanisms. Like I don’t mind having FDA approved drugs, building codes, vehicle safety standards, etc, but the issue is making anything outside these bounds illegal.

Scott Sumner

Oct 9 2023 at 4:16pm

Actually building codes contribute to homelessness, and especially hurt lower income people. We’d be better off without them.

steve

Oct 10 2023 at 8:44am

Any data on that? Absent building codes lots more people are killed in fires, buildings are destroyed and people die in earthquakes, hurricanes and tornadoes. How much more homelessness is there compared to excess damage and deaths?

Steve

Dale Doback

Oct 10 2023 at 2:00pm

Building codes, like other trade industry standards, are going to exist regardless if they have the force of law or not. We’re never going to go “without” building codes. Privatizing something like that at this point seems like it would just cause needless chaos.

Thomas L Hutcheson

Oct 9 2023 at 3:34pm

Yes, but compared to no “regulation” at all?If only the worst thing about our tax laws or externality regulating laws, or ways of transferring income for health care was that they are complex!

Matthias

Oct 10 2023 at 12:45am

I like to call regulation-favouring-big-businesses by the term economics of scale in compliance.

Btw, regulation of that kind not only favours big companies that can afford the lawyers and accountants, but also favours informal arrangements. If you are too small to get caught, the black market or operating under the table can be lucrative.

tpeach

Oct 10 2023 at 2:09am

I generally agree. But there’s certain examples where I can’t see any significant cost of the regulation, particularly around information asymmetry.

As an example, what about regulations which mandate that children’s pyjamas are made of material that isn’t highly flammable? What’s the downside in that?

steve

Oct 10 2023 at 11:27am

They cost a little more or you have fewer choices. . You should have the option of toasting your kids if you want. (Interesting note. The Victorians used celluloid in a lot of their clothing and many women burned to death. It’s very flammable. They also used arsenic in their make up and a lot of other harmful stuff. But they didnt have regulations.

Steve

TravisV

Oct 10 2023 at 12:35pm

[Sigh] Stories from this morning. Fed officials continue to reason from changes in interest rates……

Stocks climb amid hopes Fed is done with hikes: Stock market news today (yahoo.com)

Treasuries Pare Gains After Jumping on Signs Fed May Be Done (yahoo.com)

“The Fed speakers “seemed very much on the same page in noting higher bond yields and tighter financial conditions will impact their thinking on the Fed funds rate,” said Andrew Ticehurst, a rates strategist at Nomura Holdings Inc. in Sydney. “Market pricing suggests the Fed likely won’t hike this year,” he said, adding there may still be a risk of a final “insurance” increase.

Fed Vice Chair Philip Jefferson said he’s watching the increase in Treasury yields as a potential further restraint on the economy even though the rate of inflation remains too high. Fellow policymaker Lorie Logan said the recent increase in long-term yields may indicate less need for the central bank to raise rates again.”

TravisV

Oct 10 2023 at 1:22pm

Prof. Sumner,

Also please check out this five minute video of Michael Darda below on October 5th. We know he’s well-versed in market monetarism. But despite that, he still seems to believe in long and variable lags (at least of some sort)……

https://www.cnbc.com/video/2023/10/05/headed-into-q4-economic-indicators-suggest-additional-stress-says-roth-mkms-michael-darda.html

Comments are closed.