Many economists argue that the way to reduce inflation is to create “slack” in the economy, i.e., somewhat higher unemployment. I believe that’s a mistake. Unemployment is often an unfortunate side effect of reducing inflation, but doesn’t cause lower inflation. David Beckworth recently interviewed Ricardo Reis, who had this to say about the Phillips curve:

[T]he way I understand monetary policy is, whereby tightening monetary policy, a central bank is able to bring inflation down. In the same way that when I go to the doctor with an infection with a bacteria of some kind, antibiotics are the way to kill the bacteria and cure me from that. However, a side effect, and I emphasize, let me say it slowly, a side effect of raising interest rates is that you also cause a recession. You also lead to an increase in unemployment. In the same way that a side effect of taking antibiotics is that they tend to wreak havoc with your gastrointestinal, digestive system.

Note that it is not a channel. It’s not by taking antibiotics and screwing up my intestines that I therefore kill the bacteria. No, no, it’s a side effect. Likewise, raising interest rates lowers inflation and has a side effect of unemployment, but it may not lower unemployment the same way that you may go through a course of antibiotics and be perfectly fine with your gastrointestinal system. So the fact that unemployment has not gone up, does not in any way discredit the way in which monetary policy works, does not pose a puzzle of any kind, because an increase in unemployment following a tightening of monetary policy is not something that has to happen for inflation to fall. It’s something that often happens as a side effect.

This is also how I look at the Phillips curve.

My only quibble is that Reis seems to equate tightening of monetary policy with higher interest rates. That is often the case, but (as with the inflation/unemployment correlation) not always. The tight money policies of 1929-32 and 2008 were associated with sharply falling interest rates. It makes more sense to view rising interest rates as a common side effect of tight money, just as rising unemployment is a side effect that frequently occurs with lower inflation. But just as high unemployment is not the cause of falling inflation, rising interest rates are not the cause of falling inflation. Instead, it is tight money that reduces inflation.

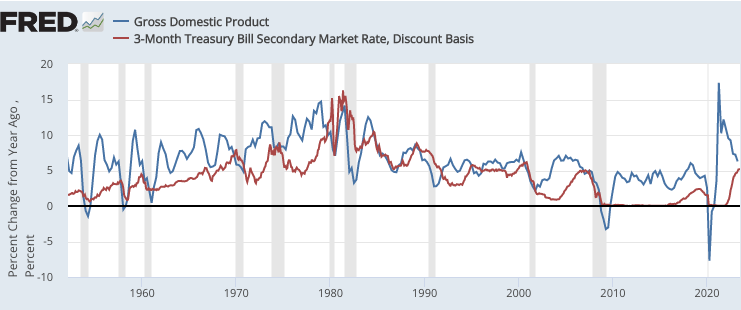

PS. There’s been a great deal of puzzlement about the fact that NGDP growth remains well above trend, despite a dramatic rise in interest rates that began in early 2022. But this should be no surprise, and indeed is almost the norm. For instance, the Fed began sharply raising interest rates in the spring of 2004, and NGDP growth remained at or above trend in 2005, 2006 and 2007. There are similar examples throughout US macroeconomic history:

Generally speaking, interest rates are a somewhat procyclical variable. For instance, they rose almost continuously throughout the 1960s. So there’s no reason to assume that higher rates will be associated with economic weakness. It depends entirely on why interest rates have increased. (Or if you prefer, whether they have risen relative to the natural rate of interest.)

READER COMMENTS

BC

Aug 7 2023 at 2:39pm

Five-yr TIPS breakeven inflation has fluctuated in the range 2.0-2.4% for the last few months, so the market seems to expect the Fed to bring inflation down to near its target over the next few years. Does that mean that chances are good for a soft landing? If breakevens were much higher than the Fed’s target, then bringing inflation down to the target would mean lower than expected inflation, which could mean a recession if nominal wages were too high due to the high expected inflation. But, if the market participants expect the Fed to hit its target, then labor markets shouldn’t be surprised when the Fed does indeed hit its target. So, as long as inflation expectations remain anchored near 2%, then doesn’t that mean prospects for a safe landing are good?

Do hard landings result mainly from either (1) the Fed overshooting to the downside or (2) the Fed losing credibility on the high side then surprising the market when it does bring inflation down even if it doesn’t overshoot its target?

What do you think about Powell’s recent statements that he doesn’t expect 2% inflation until 2025 or so? Not only doesn’t the Fed try to correct for past mistakes, it doesn’t even let bygones be bygones, which would mean aiming for 2% the next year. If the Fed misses its target one year, it seems to plan to miss in the same direction the next year, albeit by less than the year prior. At least, it does so symmetrically, so very long term inflation expectations seem to remain anchored. However, that must increase both inflation and recession risk and risk premiums (relative to letting bygones be bygones) because markets can expect demand shocks to last longer, right?

Scott Sumner

Aug 7 2023 at 3:50pm

Some of those questions have been addressed in recent posts, like this one:

https://www.themoneyillusion.com/expecting-the-unexpected/

This is a good question:

“Do hard landings result mainly from either (1) the Fed overshooting to the downside or (2) the Fed losing credibility on the high side then surprising the market when it does bring inflation down even if it doesn’t overshoot its target?”

I think both are pretty important, in the sense that avoiding either mistake would go a long way to reducing the problem of recessions.

vince

Aug 7 2023 at 3:06pm

What has the Fed done besides push short term rates up to tighten money–reduce the monetary base?

Scott Sumner

Aug 7 2023 at 3:52pm

Prior to 2008, reducing the monetary base was pretty much the Fed’s only important tight money tool—along with forward guidance about future reductions in money growth.

Now they also have interest on bank reserves.

vince

Aug 7 2023 at 5:51pm

How is the monetary base even managed in the ample reserve regime? By monitoring interest rates? Tightening by OMO pulls reserves out of the monetary base. At the same time, tightening by raising IOR pulls reserves into the monetary base.

Scott Sumner

Aug 7 2023 at 6:54pm

Open market sales reduce the base, and vice versa.

vince

Aug 7 2023 at 7:19pm

At the same time OMO reduces the monetary base, an increase in the rate on reserves increases the monetary base. I’m not sure how the monetary base provides useful information.

Jon Murphy

Aug 7 2023 at 7:55pm

I don’t think so. The higher the rates are, the more banks will keep money in reserves rather than lending it out, reducing the money supply

Scott Sumner

Aug 7 2023 at 10:33pm

Jon’s right, IOR doesn’t directly impact the base.

vince

Aug 7 2023 at 10:42pm

Wouldn’t a higher rate on reserves encourage banks to keep more at the Fed?

Jon Murphy

Aug 8 2023 at 6:03am

Yes, which reduces the money supply, not increase it.

vince

Aug 8 2023 at 1:26pm

My question was about the monetary base. Reserves are the main component of the monetary base. If banks put more in reserves, the monetary base increases.

Jon Murphy

Aug 8 2023 at 8:40pm

Not if it’s pulled from circulation, which is the point of the reserve rates

vince

Aug 8 2023 at 10:02pm

Reserves are part of the monetary base. You’re referring to broader aggregates. Apparently, the answer is that the monetary base by itself is no guide to the tightness of monetary policy.

Jon Murphy

Aug 9 2023 at 7:04am

Monetary base is a broader aggregate. It is reserves + currency in circulation. When a bank takes money from circulation (eg loaning it out) and deposit it into their reserves at the Federal Reserve, then the monetary base does not change.

Interest on reserves does not directly impact the monetary base.

Think of it like this: I have $200 total, $100 in checking and $100 in savings. If I take $50 from checking and move it to savings, I still only have $200.

vince

Aug 7 2023 at 3:08pm

Interest rates, of course, aren’t one rate. There’s an entire yield curve. If the Fed only controls the very shortest part of that curve, is the Fed being given too much credit for the yield curve increase? For example, the FFR rose in March 2022. The 10 year Treasury rose in January 2022.

Todd Ramsey

Aug 8 2023 at 10:33am

Re: “seems to equate tightening of monetary policy with higher interest rates”.

It’s puzzling how pervasive this belief is, even among economically literate writers. Even though these writers almost certainly understand that a component of interest rates is expected inflation.

Do you think this is a vestige of people’s understanding of monetary policy during the gold standard? That people have just never unlearned what they learned in Macro 101?

What, if anything, can be done to reframe people’s thinking? I know you’ve been trying for 15 years.

Kenneth Duda

Aug 8 2023 at 5:10pm

Todd, I find this baffling. The media parrots the ridiculous story that “raising rates cools spending by making it more expensive to borrow, leading people to delay purchases.” But then, they have to explain why raising rates doesn’t always seem to work, and the answer is, “long and variable lags.” Please! Any theory that includes “long and variable lags” is no more useful than predicting that eventually, the storm will pass and the ocean will be flat again.

This is doubly frustrating because the right answer seems so simple. People spend based on their expectations of future nominal income. Anything that reduces people’s expectations of future income reduces their spending immediately. Lower nominal spending means lower inflation, because the inflation rate is simply the nominal spending growth rate minus the real growth rate. Tighter monetary policy is definitionally anything the central bank does that reduces people’s nominal income expectation. Interest rates are an epiphenomenon.

Fortunately, the Fed has been moving towards a more “data driven” approach since 2008-9, and I think this approach looks a lot like NGDP Targeting in practice. What a huge improvement over Philips Curve models and the Taylor Rule.

Kenneth Duda

Menlo Park, CA

Kurt Schuler

Aug 8 2023 at 8:43pm

As a first approximation it is adequate to equate tightening monetary policy with higher interest rates. Name me the central bank that has ever *lowered* interest rates to make monetary policy tighter.

Scott Sumner

Aug 9 2023 at 11:29am

Switzerland in January 2015. More importantly, just because central banks generally intend for rate hikes to tighten policy, does not mean that rate hikes in fact tighten policy. The Fed thought the rate hikes of the 1960s tightened policy. They were wrong.

Kurt Schuler

Aug 9 2023 at 6:29pm

Good try, but it wasn’t just a reduction of interest rate further into negative territory. At the same time, the Swiss National Bank discontinued the peg of the Swiss franc to the euro to allow the franc to appreciate, which was an implicit tightening. The reduction in the interest rate was intended to partly offset it and prevent the implicit tightening from being too big.

Scott Sumner

Aug 10 2023 at 11:04pm

Rate hikes NEVER happen in isolation. There’s always something else.

Rajat

Aug 9 2023 at 7:47am

I thought you were going to praise this passage:

Scott Sumner

Aug 9 2023 at 11:26am

Good observation. Yes, I’ve used a similar analogy.

Comments are closed.