On June 17, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent tweeted:

Recent reporting projects that stablecoins could grow into a $3.7 trillion market by the end of the decade. That scenario becomes more likely with passage of the GENIUS Act.

A thriving stablecoin ecosystem will drive demand from the private sector for US Treasuries, which back stablecoins. This newfound demand could lower government borrowing costs and help rein in the national debt. It could also onramp millions of new users—across the globe—to the dollar-based digital asset economy.

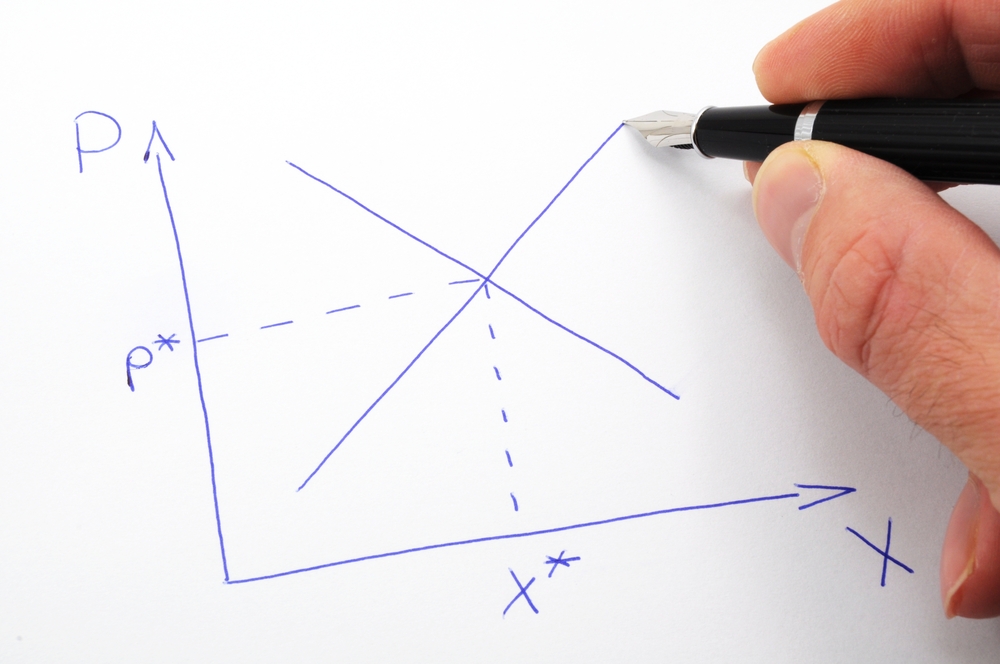

Bessent makes two Econ 101 errors in this tweet. First, as pointed out by my old GMU professor Larry White, increasing demand for Treasury bills would increase the equilibrium quantity of those bills exchanged in the market. In other words, it would increase the quantity supplied of US government debt, not lower it. [Update 7/8: this sentence originally said “increase quantity demanded” when it should have said “quantity supplied.” Thanks to Craig Richardson for pointing out the error on Facebook. I also added the following sentence, at Craig Richardson’s suggestion.] Following an increase in demand, you have higher prices and higher equilibrium quantity.

Secondly, as interest rates fall,* the cost of borrowing for the government falls, too. It’s the law of demand: as the cost of something goes down, the quantity demanded rises. People will want to hold more debt and the government will want to issue more debt. So, if Bessent is correct that stablecoins will be a “thriving” market, then the incentives would be for more government debt, not less.

Now, it is possible that Secretary Bessent read my EconLog post from about a year ago where I argued:

The people making spending and budgetary decisions do not face the full costs of their decisions. Neither do voters (indeed, the costs are spread out across all taxpayers). Consequently, we end up in a situation that James Buchanan and Richard Wagner call “Democracy in Deficit”: politicians prefer easy choices over hard, and will generally support higher spending and lower taxes.

In this case, the supply of Treasury bills is unrelated to the price level of Treasury bills: the supply is perfectly inelastic (a vertical line, for those of you drawing along supply and demand graphs at home). But, in this case, the Treasury Secretary is still incorrect in his assessment. If the amount of borrowing is unrelated to the price, then an increase in demand would lower the interest rate, but it would have no effect on the amount of debt issued. It would still be incorrect to claim that the Federal Debt would be reined in.

While it is theoretically possible that the demand curve for Treasury bills slopes upwards (although I am not sure why Treasury bills would be a Giffen good), it’s empirically unlikely.

—

*For those not well-versed in monetary economics: the prices of bonds and their interest rates (also known as the bond yields) move in opposite directions. If the price goes up, the interest rate goes down. If price goes down, interest rates go up. The price of the bond is what you pay for the bond. The interest rate (yield) is what is paid to the holder of the bond over and above the price at maturity.

READER COMMENTS

David Seltzer

Jul 8 2025 at 9:02am

Jon: Scott Bessent founded Bessent Capital Hedge Fund. His econ 101 error is coupled with his finance 101 error. To wit. Not understanding the inverse relationship between bond rates and bond prices? Of course he could be speaking as a political mouthpiece for the administration. Otherwise if he doesn’t understand bond pricing, I will gladly take the other side of any bond trade his fund makes.

Jon Murphy

Jul 8 2025 at 9:10am

I suspect that is what is going on. At least, I think that is the most charitable explanation. He has had a successful investing career, and either he was extraordinarily lucky or he does understand these relationships.

Garrett

Jul 8 2025 at 9:27am

I’m not endorsing this view, but I think one could argue if interest were lower then the budget could be lower which would require less debt issuance

Jon Murphy

Jul 8 2025 at 9:41am

That argument would make a related error: the lower interest rates would increase quantity demanded, not reduce demand itself.

Craig

Jul 8 2025 at 10:44am

“If the amount of borrowing is unrelated to the price” — they’re going to borrow the deficit right now one way or the other

“then an increase in demand would lower the interest rate”

Bonds up / yields down.

” but it would have no effect on the amount of debt issued.”

Yes, it would, it has and it does because the government is borrowing to cover the interest expense. So if the interest expense is less they will borrow less to cover it.

Craig

Jul 8 2025 at 10:25am

Rein in is a bit over the top of course, more like ‘marginally decrease the interest expense incurred by the federal government’ would be better, but even that could add up to billions of dollars. He is generally correct though, if the stablecoin acts to increase the liquidity of US debt, the shift in the demand curve, not just QD here, will make bond prices higher and thus yields lower.

Jon Murphy

Jul 8 2025 at 10:32am

He’s not generally correct. As I explained in the post, the mechanism you and he describes leads to increased interest expense (since the quantity demanded is higher), not less.

Craig

Jul 8 2025 at 10:52am

On this one you have absolutely no idea what you’re talking about. If Bessent is correct about the impact of the stablecoin on the market, the stablecoin will increase the, already liquid, nature of treasuries, that increased liquidity fuels demand, bond prices up, yields down, interest expense will be lower than it would be otherwise.

Jon Murphy

Jul 8 2025 at 11:08am

Watch your tone.

This part is correct.

This part is incorrect, for reasons explained. Merely repeating it is not helping your case.

Besides, note that Bessent disagrees with you.

Craig

Jul 8 2025 at 11:26am

JM “Watch your tone.”

Craig: On this topic YOU’RE the ‘internet rando’ so go stick it. On this topic you’re out of your sandbox and I’m in mine.

Craig: “bond prices up, yields down”

JM: “This part is correct. ” <–stick with that then

Craig: “interest expense will be lower than it would be otherwise.”

JM: “This part is incorrect”

Interest expense will be lower

JM: “Besides, note that Bessent disagrees with you.”

No, I’m {conditionally} agreeing with Bessent…

Bessent tweeted: “This newfound demand could lower government borrowing costs”

And with respect to that portion of the tweet I am agreeing with him subject to how well the stablecoin is or isn’t received by the market: “This newfound demand [bond prices up] could lower government borrowing costs [yields down]”

Jon Murphy

Jul 9 2025 at 8:58am

Watch your tone. I am the one who holds a PhD on this topic and teaches it for a living

Craig

Jul 9 2025 at 11:00am

“Watch your tone. I am the one who holds a PhD on this topic and teaches it for a living”

No you have a PhD in ECONOMICS you’re failing Finance 101. And you just recently got it and flat out you haven’t earned your stripes yet. I’m credentialed on this topic and I didn’t teach it for a living, I did it for a living.

Knut P. Heen

Jul 11 2025 at 7:38am

Jon, you don’t teach finance, you teach economics. There is a significant pay-gap between these professions. It is not the same thing. Brealey, Myers, Allen, and Edmans: Principles of Corporate Finance is a very good introduction to finance. Read it.

Bonds are usually issued with coupons and the coupons have traditionally been a fixed percentage of the principal (i.e. fixed interest loans). The fact that the bond price changes in the second hand market, does not change the coupon payments for the issuer. The bond price is only relevant for new issues and repurchases. Obviously, if you issue new bonds to finance a new project or to roll-over maturing bonds, you have to issue fewer bonds when the bond price is higher. That implies that your debt is lower than it otherwise would be.

Now, with cheaper financing, you may want to finance additional projects. That is a second-order effect going in the opposite direction from the first-order effect. I generally doubt the second-order effect is stronger than the first-order effect.

Bessent’s comment makes more sense than the demand and supply stories I see here. Pieces of paper promising stuff is not a scarce commodity. Demand and supply is therefore irrelevant. What matters is whether the promise will be kept or not.

Jon Murphy

Jul 8 2025 at 11:13am

Craig-

The problem here is you are ignoring Bessent’s claim; you’re cherry-picking parts of it while ignoring the whole thing. One should not do that. His claim is causal:

You cannot just cherry-pick [1] while ignoring [2]. Cherry-picking leads to bad conclusions.

Craig

Jul 8 2025 at 11:35am

I’m not cherry picking it

“Recent reporting projects that stablecoins could grow into a $3.7 trillion market by the end of the decade. That scenario becomes more likely with passage of the GENIUS Act.” — I am making no projection as to how well received a stablecoin of this nature will be one way or the other.

“A thriving stablecoin ecosystem will drive demand from the private sector for US Treasuries”

On this he is correct, if its ‘thriving’ then that presupposes the stablecoin would be well received by the market and then…..IF SO….

“This newfound demand could lower government borrowing costs”

And all things being equal he’s right it will lower borrowing costs beyond what they would be otherwise.

“and help rein in the national debt.”

I noted how ‘rein in’ is an over the top description

“It could also onramp millions of new users—across the globe—to the dollar-based digital asset economy.” Again if its ‘thriving’ that would be one very possible outcome not dissimilar from many people not buying bonds directly but by having money market deposits indirectly tied too treasuries, it allows for bonds to become more fractionalized to potential buyers that at the moment would find it inconvenient to park their money in treasuries at the moment.

Jon Murphy

Jul 9 2025 at 9:12am

Its not over the top. It’s flat out wrong. That’s the point of this post. He’s not “generally correct” or “over the top.”

Craig

Jul 9 2025 at 10:48am

“Its not over the top. It’s flat out wrong. That’s the point of this post. He’s not “generally correct” or “over the top.””

No, he IS generally correct because the borrowing costs will be some degree lower IF the stablecoin has the impact he is projecting it to have ie 1. broaden the market for treasuries and 2. make the treasuries that much more liquid. His projection itself is rosy but JPMorgan is projecting $500bn instead of $3.7tn market which while obviously much smaller would still have some impact albeit an impact that would be much smaller. The reason ‘rein in’ is over the top is because the term implies that this scheme will, in and of itself, rein in the debt. Of course even if it lowered borrowing costs to zero, it still wouldn’t do that.

“A thriving stablecoin ecosystem will drive demand from the private sector for US Treasuries, which back stablecoins.” — Yes, it could because this feature makes treasuries more liquid. And IF SO:

“This newfound demand could lower government borrowing costs”

Yes, absolutely he is 100% correct on that point. The issue then is only one of degree.

Ike Coffman

Jul 11 2025 at 10:56am

I am going to take sides here; Jon, you are right, Craig, you are wrong.

Why?

Support of the stablecoin has the purpose of lowering the perceived cost of the BBB in order to get it passed. There were a substantial number of congressmen who had objections based on the cost of the bill, and anything that could be used to lower that perceived cost was done, whether the actual cost was lowered or not (and it was not).

Specifically, congress was able to pass a bill that allows a larger deficit because they were able to make the cost of the bill look lower. This is exactly what Jon was arguing. Forget theory and semantics, I expect exactly the same thing to happen in the future, meaning budgets with larger deficits because they can make future costs appear lower.

David Henderson

Jul 8 2025 at 10:50am

I’m not persuaded by your argument, Jon.

I’m not positive that Bessent’s premise that there will be increased demand for bonds is correct.

But you take as given that his premise is correct. So let’s follow the argument. Increased demand for bonds raises the price of bonds, which reduces the interest rate.

So far, so good.

But then you treat the government is if it’s a standard demander. Here’s where I think you’re making an assumption that could be true or could be false.

With lower interest rates on the federal debt, the deficit, ceteris paribus, will be lower. The government could choose to offset that by running a bigger deficit to issue more bonds, but that’s not at all a slam dunk. It could decide not to spend more and issue more bonds. It’s an empirical issue.

Craig

Jul 8 2025 at 10:59am

“I’m not positive that Bessent’s premise that there will be increased demand for bonds is correct.”

You might be correct, DH, but his supposition is that they are intending to make the treasury market, on the margin, that much more liquid and potentially increase the availability to a wider market of potential, albeit indirect, lenders.

Jon Murphy

Jul 8 2025 at 11:10am

I don’t think his premise is correct either. I’m just building off of it.

True, although as I argue in the blog post I link to at the end, I don’t think it’s a reasonable assumption (but Bessent’s claim is still incorrect). I think Bessent selectively treats the government as a standard demander. He’s trying to make a causal claim, but the claim doesn’t work given his assumptions.

Craig

Jul 8 2025 at 12:02pm

There are so many variables impacting the treasury market that attempting to even try to enumerate them here would be a pointless endeavor. But if we focus on one variable, liquidity, and the stablecoin acts, on the margin, to increase the liquid nature of treasuries beyond what they currently are, that one variable will make the treasuries more desirable than they would be otherwise even if all of the other variables cause demand for treasuries to fall.

Knut P. Heen

Jul 10 2025 at 5:57am

You have to be careful here. Financial economists think of all assets as almost perfect substitutes. The implication is that increased demand refers to all assets of the world. On the supply side, it costs almost nothing to increase the supply of new securities. Talking about demand and supply in the financial markets is therefore not something we usually do. We talk about arbitrage pricing (that individual assets must be priced fairly relative to all its close substitutes). Even if there is an increase in demand at the world market level, the supply curve is nearly flat. Hence, no price change. There is no demand and supply in the present value calculation.

steve

Jul 8 2025 at 11:15am

If stable coins are both back by and pegged to treasuries not sure I am seeing much of an advantage to stable coins. I am also not seeing why the amount of treasuries being held to back stable coins would necessarily affect total debt. Stablecoins might hold a larger percentage of treasuries if they got popular but total debt held would be determined by other factors. At least they are probably better than the memecoins.

Steve

Craig

Jul 8 2025 at 11:39am

“advantage to stable coins”

On the margin it increases the liquidity of treasuries to the point where they become, potentially, a ‘near currency’ because now let’s say you mow my lawn and now you want to get paid, we can just tap out phones and I can give you $100 of stablecoin paying, let’s say 3% and transfer it to you and its now automatically in your stablecoin account paying 3% and you can go to the grocery store and so on, plus foreigners could do that too. Right now the treasury market is quite liquid, but this would make it that much more liquid. Important that it actually be accepted by the market as well, and that is obviously in and of itself not something that should be taken for granted.

steve

Jul 8 2025 at 1:55pm

Or you could just give me money and I could decide what to do with it, which wont often be treasuries.

Steve

steve

Jul 8 2025 at 2:06pm

Just out of curiosity, where does that 3% come from? For treasuries it’s the US taxpayer.

Steve

Craig

Jul 8 2025 at 2:49pm

Yes government pays the interest.

“Or you could just give me money and I could decide what to do with it, which wont often be treasuries.”

Well here you are calling into question whether the stablecoin is an abstraction of the dollar that you would value. You could be correct and the concept could fall flat of course. Indeed you can do that today, you can take the dollar and temporarily stash it in a money market, right?

But now let’s say you find yourself in Buenos Aires, or you want to buy something from abroad….Bessent’s projection says $3.7tn by end of decade, JP Morgan estimate says $500bn by 2028 which is obviously far less. But that’s the future of course, difficult to see into the future!

Robert EV

Jul 8 2025 at 6:07pm

Stablecoins, on their own, do not pay interest or they wouldn’t be stable. The interest on the treasuries (assuming they are truly backed by treasuries and not something else [see DHR’s blog: https://duckduckgo.com/?t=ffab&q=stablecoins+site%3Ablog.dshr.org&ia=web ]) goes to the stablecoin issuer for their overhead costs.

I’ll keep it to one comment and add what I was going to say on the topic here: Outside of various regimes that have capital controls there’s no reason for people to sit on stablecoins, and even in those regimes the need to sit on stablecoins, per se, or more specifically US dollar stablecoins, is limited compared to buying as needed. The velocity of a stablecoin on an exchange can be extremely fast, so you don’t need many to serve the purposes of regular people who aren’t trying to manipulate financial markets.

The one reason to increase the number of stablecoins is to increase the price of bitcoin and other non-stable crypto through artificial demand. Because of this there have been times when various stablecoins were not backed by treasuries, but by other securities, including promisory notes of crypto (that they may have been used to buy!).

It is risky to assume that a stablecoin is backed, or that you, as a regular individual, can cash it out even if it is backed.

Can we financialize our way out of US government debt? I don’t know, is LTMC’s strategy a good one?

Robert EV

Jul 8 2025 at 6:13pm

To mods: Keep my previous comment in the spam filter, I’m editing it:

Stablecoins, on their own, do not pay interest or they wouldn’t be stable. The interest on the treasuries (assuming they are truly backed by treasuries and not something else) goes to the stablecoin issuer for their overhead costs. Stablecoins are not ETFs, or anything else that’s theoretically convertible to the underlying asset. They’re tokens for 1 USD (or 1 Euro, etc…).

This issuer is also the one who would ultimately redeem a stablecoin for actual cash, though to do that in large volume they’d have to sell treasuries, munis, or crypto that they’re backing the stablecoin with. In small volume the individual can list their stablecoin on an exchange and sell it for the transaction cost.

I’ll keep it to one comment and add what I was going to say on the topic here: Outside of various regimes that have capital controls there’s no reason for people to sit on stablecoins, and even in those regimes the need to sit on stablecoins, per se, or more specifically US dollar stablecoins, is limited compared to buying as needed. The velocity of a stablecoin on an exchange can be extremely fast, so you don’t need many to serve the purposes of regular people who aren’t trying to manipulate financial markets.

The one reason to increase the number of stablecoins is to increase the price of bitcoin and other non-stable crypto through artificial demand. Because of this there have been times when various stablecoins were not backed by treasuries, but by other securities, including promisory notes of crypto (that they may have been used to buy!). It is risky to assume that a stablecoin is fully backed, or that you, as a regular individual, can cash it out even if it is backed (e.g in the event of a run).

Can we financialize our way out of US government debt? I don’t know, is LTCM’s strategy a good one?

Jeff G.

Jul 8 2025 at 2:38pm

I’m with DH. I don’t read Bessent’s tweet as selectively assuming Treasury is a standard demander. I think Bessent is (reasonably) assuming that each period Treasury simply issues the appropriate amount of treasuries to cover the current debt. For example, let’s assume the treasury needs to issue $10T in treasuries this year to cover the debt and so it auctions 1-year notes at 5%. Let’s also assume it can sell these notes at par (1.00), so it raises the required $10T and supplies $10T “units” of treasuries. Then assume next year it again needs to raise $10T and so it again actions 1-year notes at 5%. Let’s assume now the demand increases and it can sell then for 1.02. To raise the required $10T it now needs to supply $9.8T “units” of treasuries. I believe this is the debt relief that Bessent was referring to.

Jon Murphy

Jul 9 2025 at 8:59am

Agreed that the Treasury is not a standard demander. I address that in my last paragraph

David Seltzer

Jul 8 2025 at 3:12pm

Jon and other commenters. From a former hedge fund risk manager…that would be me…treasury auctions are supposed to minimize the cost of financing the national debt via competitive bidding and a liquid secondary market. Traders know what happens when an auction can’t catch a bid. It’s called a bidder’s strike. When that occurs, an auction is considered weak. The result, government (actually the taxpayer) ends up having to offer investors much higher yields than the market expected, or when primary dealers have to buy a large portion of the offering. When risk-free treasuries are seen as too risky, rates rise to compensate the potential investor or dealer for increased risk over subjective certainty equivalents. My long winded point; it depends on the regime. The 10 year yield was under 3% in 2010. Three month treasuries are at 4.35% with an inverted yield curve in 2025.

Craig

Jul 9 2025 at 11:34am

“minimize the cost of financing the national debt via competitive bidding and a liquid secondary market”

Precisely the liquid nature makes the asset more attractive. Imagine if they made a rule that bonds had to be held until maturity? They wouldn’t do that, but what would happen? People would be far less likely to buy them.

“My long winded point; it depends on the regime. The 10 year yield was under 3% in 2010. Three month treasuries are at 4.35%”

Fair but those rates still reflect the liquid nature of treasuries that is baked into the price. Of course the interest rates can still fluctuate and still go up or down depending on the innumerable other relevant factors beyond the asset’s liquid nature.

Matthias

Jul 11 2025 at 9:39am

You can make the statement make sense with some assumptions:

Assume tax revenue is fixed, and assume the amount of money the government wants to spend on its regular programs is fixed.

They make up any shortfall with borrowing. Including paying for interest in what they already borrowed.

Under those assumptions, lower interest rates lead to lower debt.