Inflation in the United States and elsewhere has generated a great deal of commentary. Some, such as Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass) and Marxist economist Richard Wolff have attributed inflation and increased prices to the greed of capitalists and corporations and corporate concentration. Such claims are questionable at best.

Greed, or any kind of personal motivations, are a bad explanation for a rise in price, whether of specific goods or the general price level. If greed or self-interest are present, then they are behavioural constants. Such accounts fail to explain why prices ever go down. Are businesses less greedy when prices fall? If so, we never hear it, and that suggests motivated reasoning.

Another reason for doubt. While a corporation might have a great deal of market power, it cannot affect the entire Consumer Price Index. Inflation is also unrelated to corporate concentration. Further, prices reflect decisions by a multitude of sellers with competing interests. Sellers are too numerous to collude and fix prices, because transaction costs rise as the number of colluding actors increases. The number of people who would need to be aware of each other, meet, and agree on a price is huge. Further, price-fixing agreements tend to break down due to defectors trying to beat out the competition by lowering their prices against the majority.

More generally, prices do not result from the will of specific actors. Prices are emergent products of supply and demand. They reflect the myriad decisions of producers and consumers with a variety of preferences and differing opportunity costs. Inflation (a general rise in the price level) tends to derive from an excess amount of liquid currency available, relative to the amount of real goods and services being produced at a given moment. In simple terms, inflation is a problem of “too much money chasing too few goods”.

Overall, personal motives have no impact on specific prices or the general price level. Motives as an explanation for market equilibria is the social science equivalent of believing that hurricanes occur because the gods are angry. On the motive-centric account, greed or self-interest becomes a quasi-mystical, generalized force to be defeated, rather than a consistent (but partial) component of human nature.

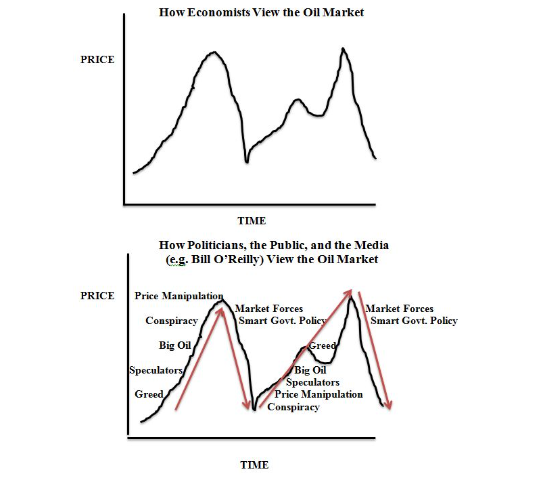

Here’s an illustrative parody by the economist Mark Perry applied to oil:

Folk intuitions and their discontents

Why are motivational explanations intuitive to so many? Such errors are common in what Paul Rubin calls “folk economics”, or “the intuitive economics of untrained persons.” Put differently, what kinds of gut feelings or patterns of informal logic mislead us, and why are they present?

One reason might be the search for control, an impulse that contributes to conspiracy theorizing (among other tendencies). Attributing causal explanations from the triumph or failure of a select group with a great deal of presumed power is easier to cope with. Compare this with explanations based on multifactorial causes resulting from the emergent patterns of many different actors. The former provides a sense of psychic security about the world as a much more simple place with problems that can be resolved through moralized struggles between defined groups. The latter does not.

This argument is related to (but not identical with) F.A Hayek’s claim that our minds are evolutionarily unsuited to the complexity of the modern world. We often reason using the logic of collective resource acquisition and distribution common in tribes, families, and other small groups with heavily shared inputs and outputs. Such groups were important for our survival in prehistory. However, centralized acquisition and distribution are not how contemporary economies with a complex division of labour function.

Tyler Cowen argues similarly in a recent book:

A related reason might be what I’ll call a desire for karmic justice. This is the idea that social or economic outcomes and patterns should track the moral virtue of actors. However, market dynamics such as inflation and price changes affect people regardless of their personal character. Likewise, all the market rewards is relative effectiveness in responding to the preferences of others and productive applications of capital. You can be a good person and do quite poorly on the market or a bad person and do very well (though markets do reward many virtues).

The idea that systems do not reflect karmic justice is likewise hard for us to accept. The invisible hand relies on the incentives of rational self-interest, not benevolence, to give people their daily bread. Likewise, economic misfortune such as inflation is caused by rational actors responding to price changes, which they too must accept as givens, and thus they are not being not strictly virtuous or vicious.

Jacob Levy notes that while ancient thinkers sought to connect the character of institutions directly to the virtue of individual actors, modern social thought since Adam Smith has recognized that the parts don’t always equal the whole. Nor is it necessary for people to be virtuous in order to create good outcomes, as reflected in Smith’s famous discussion of the invisible hand. Further, Levy argues, as in cases of perverse emergent orders, social injustice can occur without it being any individual’s intention, as in Thomas Schelling’s analysis of white flight as a “tipping point” problem.

Perhaps what popular responses to inflation tell us is that despite our highly advanced systems of economics and politics, we still need a lot of cognitive adaptation to our very abstract modern world, governed by general rules and the interactions of complex systems. Overall, they are the “result of human action, but not the execution of any human design.”

Akiva Malamet is an M.A candidate in Philosophy at Queen’s University (Canada). He has been published at Libertarianism.org, Liberal Currents, Catalyst, and other outlets.

READER COMMENTS

David Seltzer

Aug 27 2022 at 10:40am

Akiva: excellent exposition on the nature and causes of spontaneous order. Hayek’s explanation, any individual could only know a small portion of a whole which is reflected by price. Markets coordinate individual choices giving rise to spontaneous order in human social networks. Language and common law are classic examples of spontaneous order.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Aug 27 2022 at 4:13pm

This may be key to the distressingly common tendency to blame inflation on (and to think recessions can be alleviated by) fiscal policy, without regard to the role of the central bank.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Aug 27 2022 at 4:19pm

Of course a very good post could be written about “Stop Moralizing X” for any X. 🙂

Aaron W

Aug 27 2022 at 6:46pm

This is an extremely well written article about how our intuition often fails is with regard to markets and market prices. Great job! I try to explain this to people all the time but I think will just send them this instead.

vince

Aug 31 2022 at 4:42pm

Let’s moralize about Warren and Wolff. Warren panders for votes and Wolff wants to sell books. I give them the benefit of the doubt, assuming that they don’t really believe the nonsense they profess.

The solution to corporate greed-induced price increases is simple: competition.

Comments are closed.