Regular readers here know that myself and my co-bloggers (both present and former) spend a lot of time talking about the problems of central planning.[1] There are many, many problems with central planning: the Hayek-Lavoie knowledge problem, issues revealed by public choice analysis, and so on. In this post, I want to highlight a big one: creativity.

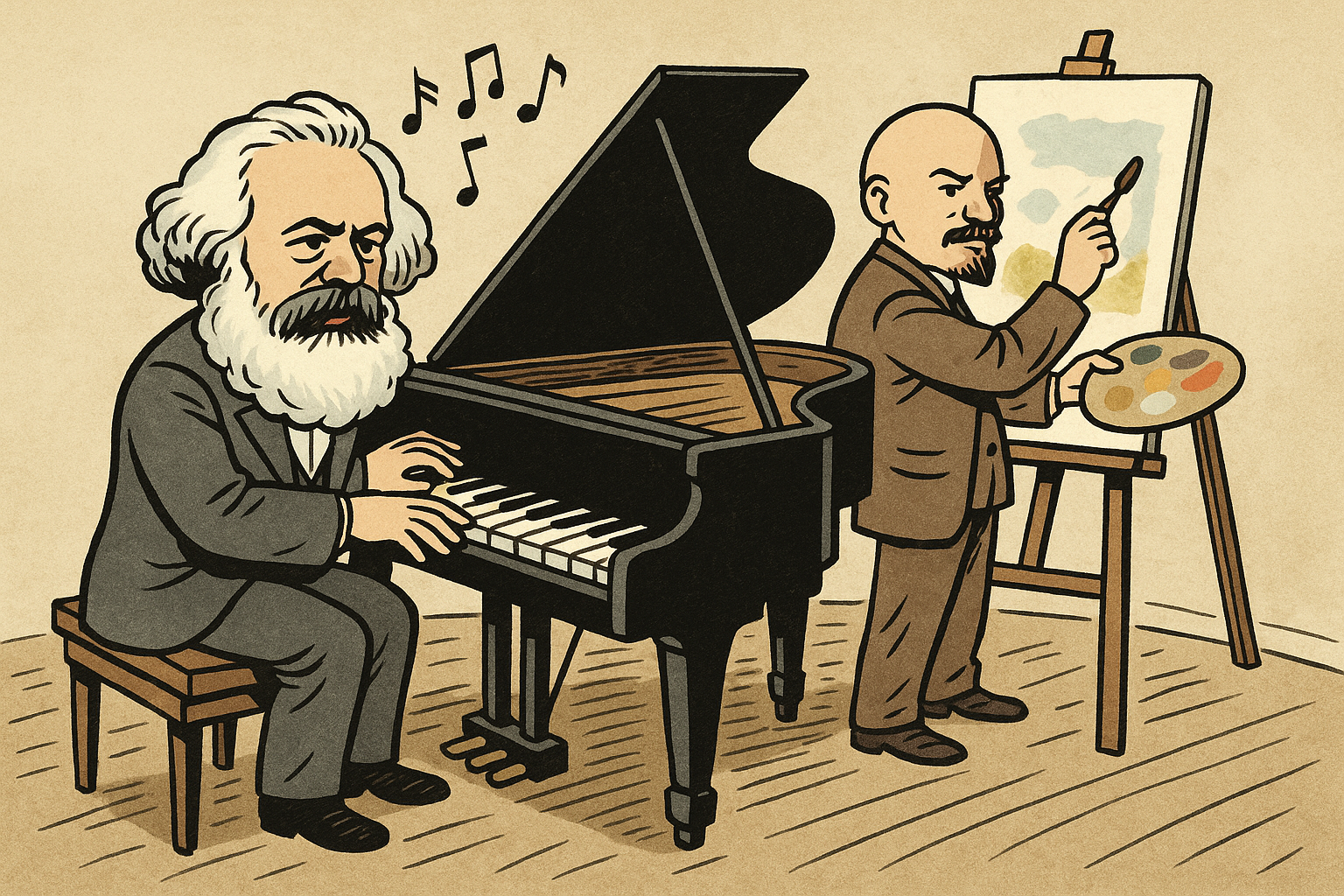

Human beings are insanely creative. Seemingly unique in the world, we are abstract thinkers and often find ways around what appear at first to be insurmountable problems. Every day, new inventions, innovations, music, and art come about to solve some problem and/or make our lives better. When we want something, we can make it happen. Indeed, Ball State University economics professor James McClure places that creativity as the core of economics:

The economic problem of society is rapid adaptation, in the face of resource scarcity, to changes in the particular circumstances of time and place.

This creativity is a problem for central planners. Central planners tend to think of the economy not as a complex system of relationships among people, but as a system that’s more like water flowing through a pipe. If you don’t like the course, simply pull some lever and change it.[2] What central planners fail to appreciate is that the economy is not like water in a pipe, but rather the result of billions of people pursuing their goals, given their constraints and alternatives. These goals are chosen by the people themselves. And when barriers toward those goals are thrown up, say by some central planner who wants the people’s goals to be different, people find creative ways around those barriers. Those creations may be illegal in nature (e.g., smuggling) or may become a whole new way of doing things.

Of course, not all forms of creativity are equal. People may get creative in gaming the system to get what they want out of it at the expense of others (e.g., rent-seeking).

Regardless, creativity poses a problem for central planners when their plans do not come to fruition. The central planner must then devote more resources to their plan to check these new behaviors not aligned with the plan. And again, more resources are then consumed by people to be creative in getting around these new barriers. Consequently, we have a sort of arms race. More and more resources are spent, but there is no relative gain by either side. Even assuming the central planner’s plans aren’t frustrated, the resource cost is significantly higher than expected. Consequently, other plans by the planner are necessarily frustrated. Even if the central planner didn’t suffer from the knowledge problem or face public choice constraints and had perfect information about outcomes that could be improved, this arms race tells us that it is quite unlikely that central planning can improve upon market outcomes.

Long story short, central planning gets frustrated because people are people.

——

[1] Note: Historically, “central planning” has referred to total government control of the economy. I am using the term more broadly to include all sorts of government interventions and schemes including (but not limited to): industrial planning, wartime planning, social-justice interventions like income inequality measures, “leveling the playing field,” and so on.

[2] This metaphor is deliberate. Economists borrow heavily from fluid dynamics.

READER COMMENTS

Michael Klimas

Sep 4 2025 at 2:03pm

Would add that creativity is dependent on the level of constraints imposed by governmental bodies. The magic, if you want to call it, of a capitalist culture of free market culture is that creativity is targeted to producing a good to satisfy a need. In essence, free markets provides and support the entrepeneural activity that allows creativity to flourish. In a non capitalists culture creativity is hindered and where it exist is targeted to avoiding a government constraints.

A economic course would be interesting that addressed creativity and how economic principles are involved.

nobody.really

Sep 4 2025 at 2:44pm

Is central planning ever justified (e.g., sanitary sewers combined with laws against dumping your sewage in the river)? If so, can we identify criteria for when central planning is justified?

Then does it make sense to speak of pulling levers? I know of hydrolic levers–but I think of pushing them, not pulling.

Jon Murphy

Sep 4 2025 at 2:53pm

Be careful: not everything a government does is central planning.

nobody.really

Sep 4 2025 at 3:25pm

OK, let’s back up a step: First, what qualifies as central planning? Second, are these things ever justified–and if so, can we identify criteria that distinguishes justified central planning from unjustified central planning?

(Jeez, we’re using fluid dynamics as the metaphor–but we’re not using that metaphor to discuss sewers? Seems like a lost opportunity….)

Jon Murphy

Sep 4 2025 at 3:34pm

Technically, it is just the government ownership and direction of the means of production. In this post, it is more broadly used to discuss any attempt at the government to direct an economy toward achieving some goal. I should have been more clear in that.

Can it ever be justified? In a true emergency, in theory yes. As a practical matter? Probably not.

David Seltzer

Sep 4 2025 at 7:55pm

Business owners plans also. There are enough of them such that in a diverse economy, mistakes tend to net out and not have bad macroeconomic effects. A restaurant might experience bankruptcy while others succeed. Macroeconomic effects will occur if there is a single Planner in a given industry. In a market economy, with many diverse planners, planning failures will not create the systemic problems that a central planning network would.

Thomas L Hutcheson

Sep 4 2025 at 10:39pm

A useful extension of this point would be to what extent these insights are relevant to marginal policy changes.

Jon Murphy

Sep 5 2025 at 12:17pm

James Buchanan wrote a lot on that in the 60s and 70s.

Mactoul

Sep 5 2025 at 3:47am

Inevitably the commanding heights of economy are going to be coordinated with the government. This is as true in 19c America when railways were built, and now with AI being built.

Jon Murphy

Sep 5 2025 at 5:40am

I need you to expand on what you mean by “coordinated.” In both examples you give, the government didn’t nationalize.

Grand Rapids Mike

Sep 5 2025 at 9:55pm

If we are talking about government attempting to produce a goal, then I think the subject is considerably expanded. An example, in the 1950 and 1960’s to find uses of nuclear energy, the Atomic Energy Commission, now Department of Energy, in effect created the availability of nuclear energy, resulting in nuke power providing electricity for a large percentage of homes, businesses etc.. In medicine, the government directed nuclear research has resulted in a variety of medical treatments. However what made it work, was a hand off to the private sector, where the creativity of market forces have allowed the potential to evolve, with if course a proper regulatory environment