In late 2021 and early 2022, a number of pundits warned that the Fed was moving too quickly to tighten monetary policy. It is now clear that these pundits were wrong. Not only did the Fed not do too much tightening, there’s almost no evidence that the Fed has tightened monetary policy at all, at least to any measurable extent.

Roughly a year ago, it became apparent (even to the Fed) that the economy was moving toward overheating. So why might an abrupt tightening in late 2021 have been a mistake? After all, inflation is a big problem, and tight money is the only reliable way of reducing inflation. Tight money can reduce NGDP growth to a level consistent with 2% inflation.

The standard answer is that the Fed needs to be careful, as tight money imposes pain on the labor market. And I believe that is true—we all saw what happened in 2008 when the Fed over tightened. The unemployment rate shot up to 10%.

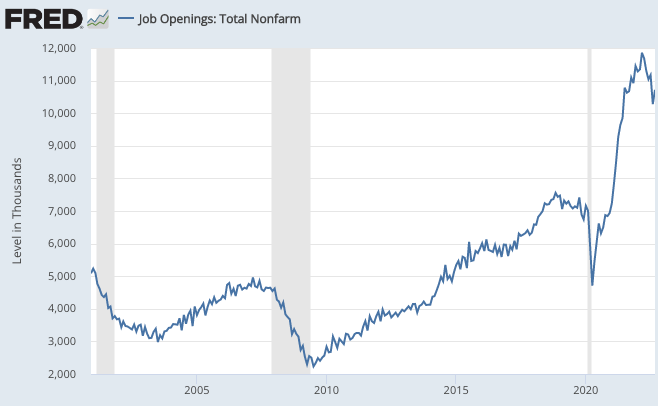

If that’s your criterion for over tightening, then the Fed certainly has not done so. Indeed not only has the Fed not imposed excessive pain on the labor market, they’ve produced such rapid NGDP growth in 2022 that the labor market is almost absurdly hot. Job openings are currently far above the level of previous boom periods such as late 2019.

A desirable policy of bringing inflation down through gradualism would balance the costs of inflation and unemployment. It would impose a modest amount of pain on the labor market, but not too much. But the Fed has not imposed any pain at all. Indeed it hasn’t even returned to labor market back down to the boom conditions of late 2019. There’s been no balancing of costs. And there’s been no significant reduction in inflation at all. Despite what you read in the press, there’s been no tight money policy in 2022.

Later this year, I plan to release a book that discusses problems in the way we measure the stance of monetary policy. Here are some mistakes that have been made in 2021-22:

1. Assuming that interest rates measure the stance of monetary policy. They don’t. Rising rates do not indicate tighter money. The money supply is also not a good indicator.

2. Gradualism in adjusting the policy instrument. It’s true that you’d like to bring NGDP growth down gradually, so as not to create a lot of unemployment. But that does not mean that you need to raise the target interest rate at a gradual pace.

3. Confusing a falling stock and bond market with tight money. (This is referred to a tighter “financial conditions”.) The most expansionary monetary policy in my lifetime (1966-81) was accompanied by a very weak performance of the stock and bond markets. Markets hate high inflation—but high inflation is not a product of tight money. Don’t equate tight financial conditions and tight money.

4. Assuming that monetary policy affects NGDP with a long and variable lag. In fact, monetary policy affects NGDP almost immediately, as we see in the few monetary shocks that are clearly identified (such as 1933). It seems like a long lag if you assume that rising rates are tight money, but they are not.

5. Too much focus on inflation and not enough focus on NGDP growth. There was a long and utterly useless debate about whether inflation was caused by supply or demand side factors. It doesn’t matter! What matters is NGDP growth, which is 100% demand driven. And NGDP growth has clearly been too high.

6. President Biden waited too long to reappoint Powell. It’s possible that Powell felt uncomfortable making the decision to tighten monetary policy just a month or two before Biden was to make his decision on a new Fed chair.

7. Most important of all (by far), the Fed’s FAIT fiasco. The Fed signaled an intention to target the average rate of inflation at 2%, just as it adopted a highly expansionary monetary policy. FAIT actually would have been a great idea, if implemented properly. But as soon as stabilizing the average inflation rate required a tight money policy, the Fed announced that the policy was asymmetric, and that they would not offset inflation overshoots with future undershoots.

In late 2019, monetary policy in the US was in a very good place, the best policy I’ve seen in my entire life. Tragically, all these gains were thrown away over the following few years, in a reckless attempt to artificially create prosperity by printing lots of money. FAIT would have been a great policy. Asymmetric FAIT has been a disaster.

PS. I got this email from Bloomberg:

It’s that time of the month—jobs day. The US nonfarm payrolls report will be scoured for any clue that the Fed can downshift to a 50 bp hike next time around or reaffirm a higher terminal rate. Evidence may be mixed: The economy probably added 195,000 jobs in October, fewer than in September but still OK.

No, 195,000 would not be OK; it would be far too high. I’m not advocating high unemployment, but is it too much to ask that the Fed at least bring the labor market back to the historically strong boom of late 2019, instead of the almost absurd overheating that we see today? In any case, Bloomberg was wrong. The economy added 261,000 jobs in October, and previous months were also revised upwards. Nominal wage growth was also above expectations. We’re still booming.

PPS. A few months back, a whole bunch of commenters told me that the US entered a recession in early 2022. These people need to reconsider their model of the economy. Ditto for those people who warned that the Fed was tightening too aggressively in early 2022. Time for some soul searching. (I did some soul searching in January, when I realized that the Fed’s FAIT was a sham.)

READER COMMENTS

vince

Nov 4 2022 at 5:35pm

1. What signs are you looking for that indicate tight money?

2. Are you suggesting the Phillips Curve remains relevant?

Scott Sumner

Nov 4 2022 at 10:40pm

Tight money would show up as slow NGDP growth.

Your second question is rather vague, so it’s hard to comment. I’ll just say that I don’t find the Philips Curve to be a particularly useful guide to policy.

Spencer

Nov 5 2022 at 8:46am

re: “Tight money can reduce NGDP growth to a level consistent with 2% inflation.”

Completely agree.

re: “The money supply is also not a good indicator.”

Disagree. In absolute terms, the money stock growth is about 2x any previous easing. M2 is mud pie. Powell eliminated the 6 withdrawal restrictions on savings accounts, destroying deposit classifications, which isolated money intended for spending, or means-of-payment money, from the money held as savings, or the demand for money (reciprocal of velocity).

Virtually all demand drafts cleared through “total checkable deposits”. See G.6 Demand Deposit Turnover release. But Powell deemphasized the role of money in the economy.

Spencer

Nov 5 2022 at 8:51am

The way you stop inflation is the old monetarist doctrine of reducing required reserves on reservable liabilities. If you examine the history of required reserves, you will find that any reduction was immediately met with a decline in prices.

Spencer

Nov 5 2022 at 8:54am

should be “increasing”

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Nov 5 2022 at 9:24am

I think it would be useful if the Fed would regularly include a retrospective showing whatever adjustment they make in their policy instruments is informed by what the now see that they should have done better in the past unless they think that paste actions were in fact best. For example, they might say we should have started raising the Fed Funds rate in Sept 2021 rather than March 2022?What do you think they should have done and when?

TGGP

Nov 5 2022 at 10:07am

Is that really true? An increase in supply can lower nominal prices, BUT it would also tend to increase quantities purchased. For example, the Jevons paradox was about how a more efficient transformation of coal into energy would result in more coal being consumed, because more transactions were worth that lower tradeoff.

Scott Sumner

Nov 6 2022 at 11:27am

An increase in the supply of a single good can boost nominal spending on that good. But aggregate nominal spending is determined by monetary policy (changes in M and V)

Todd Ramsey

Nov 5 2022 at 11:14am

Scott, do you think there is good reason for the Fed to limit any single rate increase to 50 or 75 bps? As opposed to 200 or 300 or 400 bps when the Fed feels it is way behind the inflation-fighting curve?

Scott Sumner

Nov 6 2022 at 11:28am

Ideally, I’d have markets set rates. But if the Fed insists on a target rate, then they should adjust it as much as necessary to keep NGDP on target, even if that is 300 basis points.

Rodrigo

Nov 5 2022 at 12:54pm

Professor,

Very much enjoy your fed commentary, hope you would do more do more of these. How can we get you to ask some questions at the next Powell press conference?

At any rate, what would proper fed tightening look like at this point in time?

Fed futures expect a terminal rate of 5% which is not far away and I do understand interest rates are not representative of fed stance as high interest rates usually mean loose money but its the preferred tool of the fed so we are to some extent forced to talk in terms interest rates. If indeed the fed has not tightened at all wouldn’t 5% be an inadequate terminal rate? Wouldn’t a pause result it looser money and cause interest rates to rise even more? This would be terrible for bond and equity markets. I am starting to think Powell should go to 6% or 7% and get it over with. His “everything it takes” rhetoric is not working as markets aren’t buying it, he needs to start causing real pain other than in equites and bonds.

Scott Sumner

Nov 6 2022 at 11:30am

“At any rate, what would proper fed tightening look like at this point in time?”

I don’t have a view on where interest rates should be set. The proper policy would be to create a NGDP level targeting regime.

dlr

Nov 5 2022 at 3:59pm

Not only did the Fed not do too much tightening, there’s almost no evidence that the Fed has tightened monetary policy at all, at least to any measurable extent.

probably a bridge too far, scott. nominal gdp qoq went from 14.3% in Q421 to 6.7% last quarter. final sales to domestic purchasers rose 5.1% in Q3, significantly less than the 11.7% average of 2021). and while even real rates shouldn’t be confused with the policy stance, it is almost inconceivable that the neutral two year rate has increased from -3% from late 2021 to the current + 1.8% during a period where ngdp and final sales have declined so substantially. although it is always possible to argue that these nominal declines were already expected back in late 2021, the 100bp increase in short and medium breakevens/inflaton swaps and the increase in ngdp forecasts for 2022 from the philly fed forecaster survey disagree. it seems fine to say that current fed policy isn’t tight, or remains too loose. but saying that it hasn’t tightened monetary policy at all? nah.

Scott Sumner

Nov 6 2022 at 11:35am

I don’t view monetary policy exclusively in terms of growth rates, I also look at levels. And 2021 was a recovery from 2020. The level of NGDP is currently getting further and further above the trend line, so in level terms it’s getting worse.. The 4th quarter of 2021 figure you cite is an outlier, and I pay no attention to “final sales”, which is a poor measure of nominal output.

Here’s a thought experiment. Suppose NGDP growth had been running at 4% for decades. Then one quarter it explodes to 20% due to some shock. You’d like to immediately bring it back to 4%. But what if it fell to 19%, then 18%, then 17%, etc. Surely you wouldn’t view that as path “tightening”? It would get inflation expectations more entrenched.

dlr

Nov 6 2022 at 12:56pm

<em>Here’s a thought experiment. Suppose NGDP growth had been running at 4% for decades. Then one quarter it explodes to 20% due to some shock. You’d like to immediately bring it back to 4%. But what if it fell to 19%, then 18%, then 17%, etc. Surely you wouldn’t view that as path “tightening”? It would get inflation expectations more entrenched.</em>

it depends on expectations. if the explosion to 20pct came with an expectation it would continue at 20pct (or more), regardless of the initial shock, then of course dropping it a few points is most usefully called “tightening.” this is true even if that tightening leads to a much higher nominal path than pre-explosion expectations. you are cheating by trying to isolate the shock from expectations; but expectations, like everything else, are jointly determined. if nominal expectations never jumped, then there is no need to worry about “tightening” in the first place. in this case, i am saying nominal expectations also pretty clearly rose along with inflation (year forward inflation swaps — ie ignoring the embedded oil/wheat jump, went over 4pct, for example) and have ebbed somewhat. the fed has tightened, but is not tight.

Scott Sumner

Nov 8 2022 at 11:50am

“the fed has tightened, but is not tight.”

But even that is not what the media is saying. We frequently read that the Fed adopted a tight money policy in 2022. No, the policy in 2022 has been easy money.

Matthias

Nov 7 2022 at 12:24am

Scott, do you have any explanation as for why stock markets seem to hate inflation?

Scott Sumner

Nov 8 2022 at 11:48am

It raises the tax rate on capital income.

Michael Sandifer

Nov 7 2022 at 1:15am

“…there’s almost no evidence that the Fed has tightened monetary policy at all,…”

This is where you lose me most. Since last November, we’ve got lower inflation breakevens, despite liquidity problems in Treasury markets, lower stock prices, reduced job gains, lower current inflation, lower current NGDP growth, and and inverted yield curve, including in Fed Funds futures market. How can you support such a statement? I think the Fed should [erhaps be embarrased that the yield curve inverts less than a year out in the Fed Funds futures market, as one interpretation is that the Fed is expected to have to respond to overtightening from its own perspective.

I also take issue with your statement about 2019. Inflation and inflation expectations were well below the Fed’s 2% target in 2019.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=VPWS

The 5 year breakeven, for example, fell below 1.7% at one point, in CPI terms, which in the Fed’s preferred core PCE terms is roughly 1.4% or perhaps a bit less. Also, the then current inflation rate was below 2% for the entire year in core PCE terms, reaching a low of 1.53% in November. You’ve used the expected inflation rate yourself in judging the success of their monetary policy under their previous inflation targeting regime.

Also, the treasury yield curve was negative for much of 2019:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=VQ8y

Then, there’s the fact that the Fed began lowering rates in 2019, after rate increases that began the year before. I interpret this as the Fed acknowledging it over-tightened:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/fredgraph.png?g=VQ9G

In fairness, NGDP growth was roughly at its 10 year trend during that year, so by that measure you’re okay, but that wasn’t the Fed’s criteria for policy at the time. You think the Fed should try to achieve its publicly stated goals.

More importantly, it’s expected NGDP growth that matters, as opposed to current growth, and I argue that short-run NGDP growth expectations fell precipitously in late 2018, and began recovering in 2019, leading to temporarily relatively high stock price multiples.

Michael Sandifer

Nov 7 2022 at 7:20pm

Okay, so from a level perspective, monetary policy hasn’t tightened much, but that’s looking in the rearview mirror. It’s NGDP expectations that count, rather than past growth.

Michael Sandifer

Nov 7 2022 at 1:50am

I hope you’ll share your explicit model of the relationship between stock prices and NGDP growth. You’ve mentioned an inverted U-shaped relationship between inflation and stock prices. Does this have to do with the discount rate, as affected by inflation? I think the flat nominal and negative real price growth in the 70s was primarily due to inflation-related tax bracket creep.

Scott Sumner

Nov 8 2022 at 11:51am

Easy money helps stocks when the economy is depressed, and hurts stocks (via higher tax rates on capital income) when the economy is at full employment.

Michael Sandifer

Nov 8 2022 at 8:58pm

Scott,

Yes, there is some truth to your claim, but not like there was in the 70s. Inflation expectations at, say 3%, which represent easy money under a 2% inflation targeting regime, won’t make much of a difference.

Comments are closed.