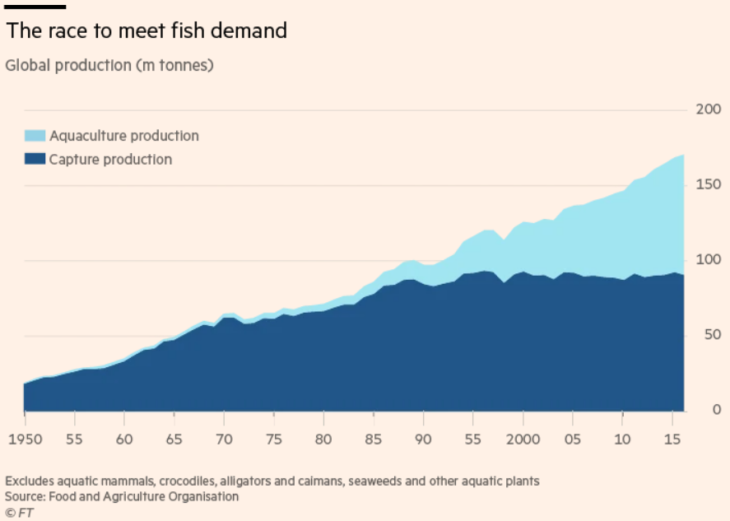

Experts often warn that we are soon going to run out of a natural resource. If so, then we might expect an increase in price, which encourages conservation. In many cases, however, that price increase unleashes a new and unforeseen alternative supply. Consider the fishing industry, which used to rely on fish caught in the ocean:

Notice that ocean caught fish peaked in the mid-1990s, and all the new supply has been coming from aquaculture.

Notice that ocean caught fish peaked in the mid-1990s, and all the new supply has been coming from aquaculture.

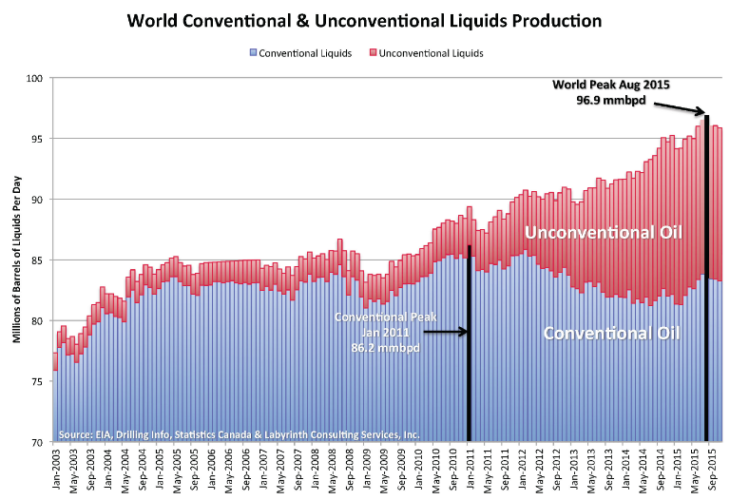

Here’s the global oil industry:

Notice that conventional oil production peaked around 2011, and all the new growth in demand is being filled by unconventional oil sources (mostly fracking.) Further back in history, whale oil was the “conventional oil” and underground petroleum was “unconventional”.

READER COMMENTS

Matthias Görgens

Sep 18 2019 at 1:20am

Reminds me of this quote from Alpha Centauri:

“Resources exist to be consumed. And consumed they will be, if not by this generation then by some future. By what right does this forgotten future seek to deny us our birthright? None I say! Let us take what is ours, chew and eat our fill.”

— CEO Nwabudike Morgan “The Ethics of Greed”

“The No Breakfast Fallacy” by Tim Worstall is a nice book on this topic. One of the big themes is that basing forecasts on how long known reserves last at current rates of consumption doesn’t tell you anything, because the stats about known reserves come from resource extraction companies that are legally required to be conservative in their estimates lest they mislead investors. (And proving a reserve to a sufficient standard is expensive, so they only do it for what they want to exploit in the near future. Hence the analogy in the title of the book of basing your long term forecasts of your personal food supply on how much stuff you currently have in your fridge.)

Jens

Sep 18 2019 at 5:42am

If one day fuel is synthesized in relevant amounts that would be unconventional oil part 3 ? The problem with these substitution processes is not that they are impossible. As long as the sun is shining energy and what can be done with it can’t be the limiting factor on this planet. Take energy that has been transformed into hydrocarbons stored in the earth crust, energy that is available in form of living organism or transform the sunlight directly – not that much of a difference at all. The real problem lies in the side effects of these transformation processes and technologies, in all the statistics related to whale hunt, aquaculture, fracking, snythetic fuels etc. not mentioned in this article. These costs are not on today’s bills and we know it.

Take for example the connection of whale hunting and southern ocean krill (Euphausia Superba), known as the “antarctic paradox” (not to be confused with any kind of antarctic ice paradoxes). Balaenoptera Musculus, the big blue whale, and other whales were hunted in the 20th century almost to extinction. A long living, slow reproducing huge animal. Populations are recovering now, steadily but slowly. These whales feast almost entirely on krill. Now one might imagine that hunting these whales might be good for krill. But it isn’t.

Marine research was done on this topic, it seems quite clear that krill abundance is much lower now than it was before whaling. This is a problem for all animals that feast on krill, not only whales, but also birds, seal, fish or squid. It appears that the phytoplankton, which is the prey of the krill, was actually fertilized quite effectively by the whales excrements that drift on top of the ocean surface. Early whale hunters did not understand that they where destroying the output (!) of a huge ecosystem by hunting whales.

Because these ecosystems are controlled mainly by feedback loops and reproduction factors ( much prey leads to too much predators leads to less prey leads to less predators .. continue ad nauseam) it can take decades or even hundreds of years for them to restore their full capacity (if all parts remains productively intact). Heck, these ecosystems are even a source of carbon sequestration because dead parts sink to the ocean ground where carbon is locked away for aeons. We could burn more oil and gas if we hadn’t killed that many whales !

Markets are ok. But they should stop destroying things they don’t understand (yet) with stupid slogans and braindead propaganda. Now one might respond that it is not possible to not destroy things one doesn’t understand. That may be true sometimes. But i think this argument can be too easily used as an excuse and scapegoat. One can be cautious and respect hints and wait for understanding to come. E.g. even whale hunters noticed that the ocean surface was changing because of declining krill populations. And most of the time destruction is not driven by accidentally triggering an unknown butterfly effect, but by use of relentless, enduring force and/or brutality. Don’t do that, read Moby Dick. Most destruction could be prevented by being cautious, alert and understanding for all the possible side effects, especially on ecosystems. Now that would be an ambitious, exceptional mode of exploring new markets.

ChrisA

Sep 19 2019 at 2:09am

Jens – in the example you give of the whales, I would argue a big issue with the whalers was that there was no market it was plundering. If whaling were a monopoly industry, with the whales owned by some corporation, maybe they would have been interested to learn how to safe guard their industry long term. Many people wrongly believe that industry can only operate short term quarter by quarter. But this is not true – a Gulf of Mexico oil industry project for instance might take 15 years from initial acquisition of the license, all the way through seismic, then exploration and appraisal and then building and installing the platform, before any oil is produced, and then it might take another 5 or 10 years before the initial cost is repaid and the project starts to make a profit. Markets are fully willing to make such long term investments as the property rights are secure, and there is little risk (at the moment) that as soon as the project begins to make a profit, these profits will be taken by the Government.

So the answer is perhaps more markets not less.

Phil H

Sep 18 2019 at 9:36am

I think the worry about this is that it’s overly optimistic. In very broad strokes: life before about 1900 really was Malthusian; life since 1900 has not been Malthusian. But that could easily be just a brief shift between one Malthusian equilibrium and another.

Balanced against the magical new resources of oil should be the collapse of the Mayans, Teotihuacan, Viking Iceland, and countless other empires.

Having said that, I do agree that in the short term, markets are about the best technology ever invented, and they should be used wherever possible. I just don’t think we should imagine that they could necessarily guarantee our future on their own. They will need some help from people who think and plan longer term.

Brian Donohue

Sep 18 2019 at 9:37am

As a freshman in high school in 1979, I was taught that there was only 25 years of oil left. The bootlicker in the front row nodded along solemnly. I wonder what she’s doing today.

Scott Sumner

Sep 18 2019 at 12:48pm

She’s probably highly successful and has forgotten about that prediction.

Brian Donohue

Sep 18 2019 at 1:38pm

I don’t doubt she’s doing well, but yes, like you suggest, I suspect she learned zero from the experience.

Michael Rulle

Sep 18 2019 at 9:40am

I read Julián Simon by accident for the first time about 12 years ago. I had never heard of him and had no predisposition to like him or not. He had written a book on using “resampling” in statistics and found his clarity on the subject enlightening. For many friends of mine who were looking to understand the basics of statistics I highly recommended him to those who had no formal mathematical background.

Gradually I discovered he was an anti-Malthusian. His belief that humanities’ greatest resource are humans themselves has been very clarifying for me as he was the first intellectual I read who approached the value of free markets from that perspective.

Of course, many share his view who preceded him, particularly from the field of economics. Progress is a function of free markets because for some reason we have been built to survive and, materially at least, advance when not inhibited.

Yet part of our human nature is to believe that we are always on the precipice of some unstoppable calamity which we must try to control. This aspect of ourselves has value. For example, the decline in cigarette smoking was not entirely a function of free market rejection. It began by government attacking it and regulating and taxing its sales and promotions. But not outlawing it.

The new Malthusian obsession is Global Warming. What if the promoters of future calamity are correct? That is, what if CO2 emissions really are leading to warming that will reach levels that will radically alter our environment for the worse? Are free markets the best way to solve the problem? To me the answer is clear——yes. Because it will be reflected in demand for goods and services to counter the negative impact.

But extrapolating far into the future as a rationale for radical action in the present has never worked—-to force and outlaw based on an unknowable future is a self destructive activity. Continuity is another Simon idea. Man adapts, and adapts well when permitted.

We already have reduced emissions, as a by product of fracking. But as the continual re-emergence of socialist/central planning shows, our greatest resource may be humanity itself, it is also our biggest threat. Free markets are a choice, not our destiny.

Scott Sumner

Sep 18 2019 at 12:50pm

Carbon taxes are probably the best solution to global warming.

Brian Donohue

Sep 18 2019 at 9:58am

Scott, this is a very good and timeless message, but I really wish you’d spend more time dancing with the girl what brung ya here. It’s not as if nothing is happening. Extraordinary movements in the bond market over the past month and a half.

On July 29, before the previous Fed meeting, the 30-year Treasury yield stood at 2.59%. After the meeting, yields collapsed, hitting on all-time low of 1.98% on August 15 (thanks, nuanced, lawyerly, needle-threader Powell.)

Toward the end of the month, people started thinking bigger (0.5% cut), and lo and behold, the 30-year yield ROSE 40 bps, to 2.37% on September 13.

Better economic news has now reduced the likelihood of a cut from a near-certainty a week ago to closer to a coin flip now:

https://www.cmegroup.com/trading/interest-rates/countdown-to-fomc.html

As a result, 30-year yields have slid again, down to 2.23% at 10:00 Eastern this morning.

I would be hard-pressed to find a more clear-cut connection between lower short-term rates and higher long-term rates.

And it’s not just that the expectation of lower short-term rates increases expected inflation (it does, obviously) but 30-year TIPS have followed the same pattern as the 30-year bond. Right now, easier monetary conditions INCREASE real (Wicksellian?) long-term yields, but all the sages (Wall Street in particular) don’t grok this at all.

It’s a beautiful natural experiment.

Scott Sumner

Sep 18 2019 at 12:54pm

You’ll find I still do many posts on monetary policy, much more than any other topic.

Brian Donohue

Sep 18 2019 at 1:41pm

That’s what I’m here for. Been kind of a thin gruel of late on monetary policy, despite significant doings afoot. Great post on China over at TMI btw. Of course, you’re old and semi-retired and are perfectly within your rights to write about whatever the hell you want. Cheers.

Thaomas

Sep 18 2019 at 5:42pm

If we could just get people to understand how this applies to the “supply” of low CO2 air! Supply and demand will work if the price of net CO2 emissions is not held down at zero.

Lorenzo from Oz

Sep 21 2019 at 10:19pm

So, if such things as peak oil and peak fish are not working out, the demand for apocalyptic doom has to go somewhere else?

Perhaps a surge in apocalyptic doom about climate change?

Oh, wait …

Comments are closed.