There’s been a great deal of discussion of what we can learn from the Covid policy adopted by Sweden. One side suggests that the Swedish outcome shows that lockdowns don’t have much impact on Covid infection rates, while the other side reaches the opposite conclusion. I’m rather skeptical about the effectiveness of lockdown policies, but I don’t entirely agree with either side of the debate over Swedish policy. (This article in The Economist is also mildly skeptical of the cost efficiency of lockdowns, accounting for both the impact on the economy and on human freedom.) At the same time, I’ve long suspected that the Swedish government didn’t handle the epidemic very well. That requires some explanation.

Scott Alexander has a very long and thoughtful article on the effectiveness of lockdowns, and does a good job of presenting both points of view. Here’s what he says about Sweden:

Anyway, a reasonable conclusion might be that Sweden had between 2x (if we compare it to an average European country) and 6x (if we compare it to an average Scandinavian country) the expected death rate in the first phase of the pandemic.

Philippe Lemoine is extremely against this conclusion. He first argues that since we don’t know why Finland+Iceland+Norway+Denmark did so well, we can’t assume it’s a “Scandinavia effect” and so we can’t assume Sweden would share it. Therefore, we should be judging it against the European average rather than the (better) Scandinavian average. I would counter that, although we can’t prove that just because X is true of Finland+Iceland+Norway+Denmark and not other European countries, that it should also be true of Sweden, but we should have a pretty high prior on it . . .

That’s exactly my view. In the past, I did a cross-sectional study of developed countries, and while doing so I found that the Nordic countries are actually quite distinctive. According to a wide range of measures they are quite similar to each other and quite different from other countries. So I have the same prior as Alexander, and thus lean toward the view that Sweden really did do much worse. But . . . I don’t believe this was primarily due to Sweden’s lockdown policies.

Recall that Sweden is just a single data point. When we look at more systematic studies, the effect of lockdowns seems to be much smaller. Here is Alexander, citing a study of US states that found some impact from lockdowns:

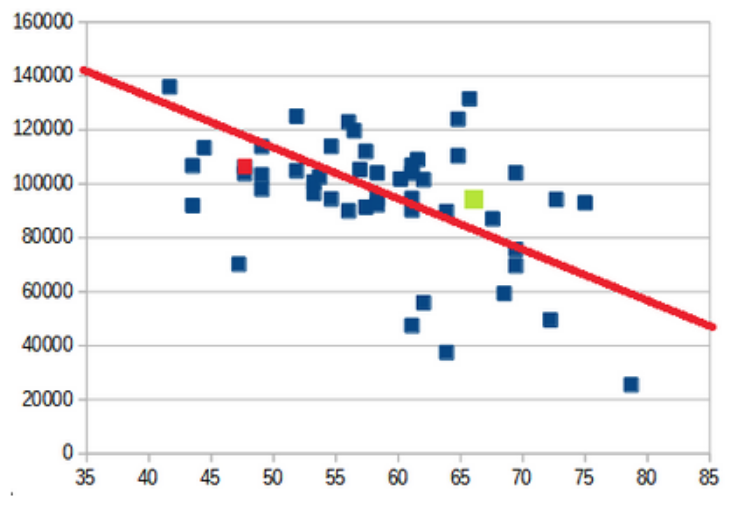

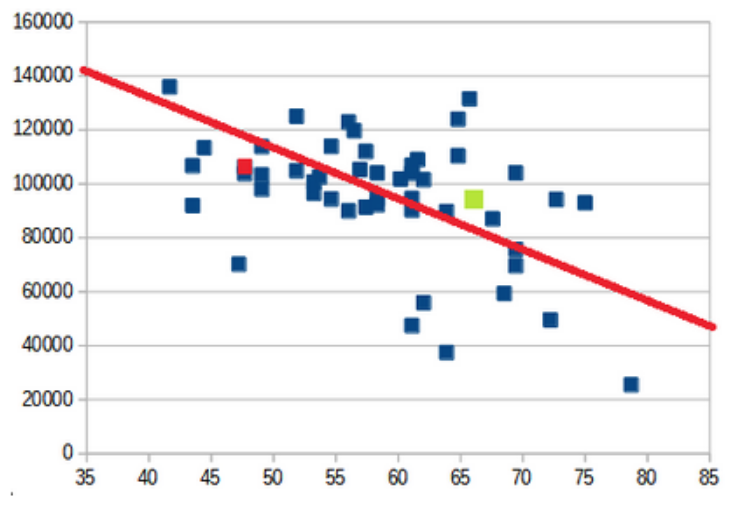

This is a victory for lockdowns insofar as the correlation is significant, but strong proponents might be surprised by how small the effect was. A few small isolated northern states like Vermont did very well. But most states – from California [green dot] and New York to Florida [red dot] and Texas – clustered in a band between 80,000 and 120,000 cases per million. States at the 75th percentile of lockdown strictness had about 17.5% fewer cases per million than states at the 25th percentile.

And even that may overstate the effect, as people in states with stricter lockdown policies might also contain people that would be more careful in the absence of lockdowns. On the other hand, Alexander points out that there was lots of voluntary behavioral change in states with weak lockdown policies, so this doesn’t suggest that we should have just lived life as normal during Covid, rather it casts some doubt on mandatory lockdowns having much marginal benefit.

So why did Sweden do far worse than its Nordic neighbors while places like South Dakota did only marginally worse than states with more restrictive lockdowns? I don’t know, but I suspect it might have had something to do with other Swedish policies. Here it’s useful to recall that Sweden has a high level of what’s sometimes called “civic virtue”, which is the tendency of the public to cooperate with what is seen as sound public policies. Sweden is a “high trust society”. And at least early on in the pandemic, some Swedish public officials seemed to be recommending a “herd immunity” approach to the pandemic. Consider the following, from August 2020:

While most of the world has come to terms with covering their noses and mouths in crowded places, people in Sweden are going without, riding buses and metros, shopping for food, and going to school maskless, with only a few rare souls covering up.

Public health officials here argue that masks are not effective enough at limiting the spread of the virus to warrant mass use, insisting it is more important to respect social distancing and handwashing recommendations.

“I think it’s a little bit strange. Sweden, as a small country, they think they know better than the rest of the world. (It’s) very strange,” says Jenny Ohlsson, owner of the Froken Sot shop selling colourful fabric masks in Stockholm’s trendy Sodermalm neighbourhood.

Last year, I recall reading that when Swedish people were interviewed, they cited government recommendations when explaining their lax behavior. In my view, Sweden ended up with much higher caseload than its Nordic neighbors mostly because of voluntary differences in behavior, partly attributable to dubious recommendations from the Swedish authorities. That would explain why lockdowns seemed to have had a much more damaging effect in Sweden than elsewhere; the actual problem was a range of other behavioral differences that were not directly due to a lack of mandatory lockdowns. (Some also cite Sweden’s inept nursing home management, but even that doesn’t fully explain the differences.)

So what are we left with? Lockdowns are overrated in importance in two different ways. First, they didn’t save nearly as many lives as their proponents assumed. Second, their economic cost was lower than their opponents assumed. Most of the economic damage was due to voluntary behavioral changes. But lockdowns also restricted human freedom.

On balance, I lean toward the view that the gains in public health were not large enough to offset the admittedly modest economic damage, plus the substantial loss of freedom. And this view is not based on any dogmatic opposition to any and all government regulation. If the case fatality rate had been 60% instead of 0.6%, then lockdowns might have made sense as a temporary policy. But even in that case it’s not entirely clear they would have been necessary, as the voluntary behavior response would have been far greater. Rather the restriction on human freedom that would have made the most sense is a temporary restriction on inbound airline flights.

PS. Lockdown policies had virtually zero impact on my life over the past 15 months, so my views here do not reflect grouchiness over being inconvenienced. Rather, I believe that lockdown policies did restrict the behavior of many other people.

PPS. This post does not apply to countries that successfully implemented a near-zero Covid policy, such as Australia and New Zealand. It applies only to countries where Covid was widespread. In a future pandemic, it is almost inevitable that all developed countries will try to emulate Australia, at least initially. You may not like that fact, but it seems inevitable to me.

PPPS. This issue is almost endlessly complicated, as Sweden did have some “lockdown” rules, and later in the epidemic it made the rules more restrictive in response to soaring caseloads. As a result, Scott Alexander focused mostly on the early phase of the epidemic, to minimize the “endogeneity problem”. Similarly, “herd immunity” was never the official Swedish policy, rather government officials spoke of it as a reasonable objective.

READER COMMENTS

robc

Jul 12 2021 at 7:13pm

Didnt Sweden also have the issue that their senior homes are large and so the virus spread rapidly in the worst hit demographic, while Norway has small, isolated senior homes?

IIRC, Sweden officials acknowledged early on that they made huge mistakes with regard to the elderly.

Andre

Jul 12 2021 at 8:21pm

Yes, they did so acknowledge.

Also, Sweden had an abnormally low death total during the previous year (i.e., an unusually large number of elderly made it through the winter season) – unlike their neighbors which had normal death tolls the prior year.

Andre

Jul 12 2021 at 8:38pm

Here. See for yourself.

https://www.statista.com/statistics/525353/sweden-number-of-deaths/

Adjust 2020 downward to account for the thousands who uncharacteristically survived 2019 and you’re left excess deaths for 2020 of about 1 in 3,000 people – two-thirds of whom were older than 80 and approximately 90% of whom were older than.

True, this doesn’t factor in 2021, which will no doubt be higher than usual also. But all the screaming about Sweden happened last year, when they did just fine and better than many other countries. Sweden iirc began changing its policies at the tail end of 2020.

Swedes got to enjoy their 2020 in a way few others did. And as I understand it their 15-and-unders were in school with no masks for all of 2020. I haven’t followed what they did in 2021.

Scott Sumner

Jul 13 2021 at 1:41am

You said:

“Swedes got to enjoy their 2020 in a way few others did.”

I don’t agree with this. There is abundant evidence that Swedes did a lot of social distancing. Their economy was hit just as hard as the other Nordic countries. If life had truly gone on as normal in Sweden then their death toll would have been far higher.

I don’t think there’ s much doubt that the Swedish government made serious errors and greatly underestimated the severity of Covid. As a result, by 2021 their lockdowns were at times even more restrictive than in Norway. On the other hand, I don’t think there’s much evidence that mandatory lockdowns are worth the cost.

Andre

Jul 13 2021 at 6:32am

I wasn’t in Sweden, personally. But I did see photographs of crowded parks and beaches, and a video in October of a person showing the country’s situation, how life was normal – they boarded and walked through a full train, virtually no masks, all going about their lives.

It is entirely reasonable to intuit that the vulnerable were more careful, but from what I saw, they were not practicing the social distancing rules we imposed on ourselves. Their one limit as I recall was groups of 50 people or more.

Andre

Jul 13 2021 at 6:37am

Scott, here’s the video. Watch for yourself.

https://twitter.com/JamesTodaroMD/status/1316003759059881985

(I’m not on the Twitter, but if you open it in a private window it should show)

My segue would then be, why is “Swedes really did social distance” so important a belief to cling to.

Scott Sumner

Jul 13 2021 at 12:58pm

Consider the following:

“Anders Tegnell says his modelling indicates that, on average, Swedes have around 30% of the social interactions they did prior to the pandemic.

And a survey released this week by Sweden’s Civil Contingencies Agency suggests 87% of the population are continuing to follow social distancing recommendations to the same extent as they were one or two weeks earlier, up from 82% a month ago.”

This must be roughly true, as otherwise Swedish economic output would not have fallen at similar rates to its neighbors. The Swedes were smart to keep going to parks (which is safe), and foolish not to wear masks on subways.

Scott Sumner

Jul 13 2021 at 1:37pm

link:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53498133

zeke5123

Jul 13 2021 at 11:59pm

Maybe, maybe not (I recall seeing cell phone . But you did seem to ignore the much more relevant argument Andre made (as did Scott Alexander in his not so great piece): (1) Sweden made a mistake with nursing homes which caused a spike and (2) Sweden’s population was actually pretty different because of more dry tinder compared to the rest of the Nordics. Maybe either or both are wrong, but if either is right it can explain the difference handily.

I think the bigger problem with your post (and Scott A’s) is that other Nordic countries were themselves not big into lockdown for the entire time (e.g., Finland). I guess ultimately it comes down to the measurement that was used, but I am always a bit suspicious of indexes. That is, perhaps the framing is wrong — maybe the question is why were the Nordics so good compared to Europe?

Ray

Jul 12 2021 at 9:14pm

Possible reasons for the variance between Sweden and other Nordic’s include:

Urbanization (not avg. population density) – Stockholm is a big city with a dense population. Other portions of Sweden compare favorably with the other, more rural Nordics.

Timing of holidays in Sweden with many travelers returning just at the start of the pandemic.

Misses on nursing homes.

Check out some of the interviews w/ Anders Tegnell – UnHerd is a good source.

Also, by avoiding deaths from lockdown, Sweden did better than most when it comes to all cause excess mortality.

Scott Sumner

Jul 13 2021 at 1:48am

Those factors don’t even come close to explaining Sweden’s high fatality rate. And I don’t regard Tegnell as a “good source”; he was a big part of the problem in Sweden.

BTW, density is not the issue. North and South Dakota have much higher fatality rates than Minnesota or Wisconsin, which are far more dense. And Sweden is only modestly more dense than the other Nordic countries (indeed less than Denmark.)

Scott Sumner

Jul 13 2021 at 1:51am

OK, I see you distinguished between density and urbanization. In any case, the differences are far too large to be explained by Sweden’s greater urbanization. Metro Stockholm has 2.4 million people, while metro Copenhagen has 2.1 million people. Metro Oslo has 1.6 million. None of these are giant cities like New York or London. And yet Sweden has many times more deaths per capita than the other Nordic countries.

Daniel Hill

Jul 12 2021 at 11:19pm

Except no government regulation is ever temporary. 18 months in and I and tens of thousands of other Aussies still can’t get home.

Scott Sumner

Jul 13 2021 at 12:59pm

I agree that they are currently overreacting, but life in Australia during 2020 was much better than life in America.

Warren Platts

Jul 14 2021 at 11:10am

But life in America in 2021 is going to turn out to be a lot better than in Australia..

Jerry Brown

Jul 13 2021 at 12:13am

One thing we can infer is that very few people here in the US are going to agree about what we can infer. If Sweden did 20 times worse than Norway I’m not sure how many would change their minds here. And if Sweden had done just as well as Norway, or even better, I’m not sure how many would change their minds in that case either. It’s an unfortunate situation.

MikeP

Jul 13 2021 at 2:51am

Here is the graph I have been following since August: Deaths per million in European countries over 10 million.

I watched this day by day, waiting for Sweden to separate itself from the pack. I did not have the hubris to expect that my prediction on how Sweden would end up compared to the rest of well-connected Europe was certainly correct. But pretty much everyone who disagreed with Sweden’s chosen policy did have such hubris.

Lo and behold, day by day and week by week Sweden started drifting down from top 4 to median to, now, bottom 4.

You cannot tell from this graph what countries locked down or when — more evidence that lockdowns and mandates were marginally effective at best. But Sweden is subtly different in that it shows slopes in seasons when the other countries show flats. It was late to flatten in the summer and late to rise in the winter. Most strikingly, if you switch the deaths per million to cases per million you find that Sweden’s cumulative case rate is second only to Czechia’s. Now, we all know that cases make abysmal data as they are so dependent on who is being tested and how much testing is done. But it is quite telling that Sweden’s case rate is higher than the comparable countries while its fatality rate is low. This is pretty much exactly what Sweden was trying to do: let the less vulnerable live normally to protect the more vulnerable.

We have now come far enough to tell that the Swedish response, also known as the WHO recommended response as of 2019, was the right response. The rest of the world completely lost their minds.

Scott Sumner

Jul 13 2021 at 1:00pm

Not sure what this has to do with my post. Did you read it?

MikeP

Jul 13 2021 at 2:25pm

Apologies. My comment was getting long so I took off the introduction.

What it has to do with your post is that the proper comparable for Sweden is not Scandinavia: It is Europe. It has been well known for almost a year how different Sweden is from its smaller and less connected neighbors. In this case those differences were compounded by Sweden’s circumstances of being well below average in steady state deaths, of having ski week for Stockholm at exactly the wrong time, and of not doing a good job of protecting nursing homes.

Scott Alexander too should have done some more digging on Sweden, especially before he accepted without question a Stringency Index that was frankly incompetent with regard to Sweden.

In effect, Sweden was the New York of Scandinavia. It doesn’t make any more sense to say that Sweden’s response was poor because it did worse than countries half as large and half as well connected than it does to say that New York’s response was poor because it did worse than states half as large and half as well connected.

And given the graph of Europe, and similar graphs of the United States and the world, to a first order response doesn’t matter. If your country or state is well connected, your population will get coronavirus. So better to respond like Sweden than to respond like the United Kingdom. And better to respond like Florida than to respond like California.

In the end you seem to come to the same conclusion. I guess I have become sensitized to comparisons of Sweden to the other Scandinavian countries, and I was especially sensitized by reading Scott Alexander’s post earlier. Apologies again.

MikeP

Jul 13 2021 at 3:21am

For a helpful perspective on Sweden that goes beyond the inept commentary from outside, you could certainly do worse than Sebastian Rushworth, a doctor in Sweden.

Here’s his take on the comparison with the other Nordics: https://sebastianrushworth.com/2020/12/06/why-did-sweden-have-more-covid-deaths-than-its-neighbors/

Scott Sumner

Jul 14 2021 at 4:51pm

That’s extremely unpersuasive.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jul 13 2021 at 7:31am

It is unfortunate that there has been so little discussion of what parts of “lockdowns” or voluntary behavioral change were or were not cost effective. Only a few extreme cases (nursing home failures and closure of outdoor spaces) have really come to light.

But the much bigger failure was not following the Romer-Tabarrok strategy of mass screening and isolation (which need not have been coercive) of asymptomatic infected people, half dosing, second shot delay, extreme caution in approving vaccines (and the message that sent).

Scott Sumner

Jul 13 2021 at 1:01pm

Exactly!

Brian

Jul 14 2021 at 5:16pm

FWIW, this NBER paper showed that shelter-in-place (SIP)/lockdown orders caused increased mortality, presumably because it prevented people from getting treatment for other deadly conditions. So SIP seems to have been a loser all the way around.

https://www.nber.org/papers/w28930

Ken P

Jul 16 2021 at 1:10am

Will the people comparing country/state x to country/state y to make their pet case in support of their priors please show me data from previous years where we did not have policy interventions and countries/states around the world had identical infection rates of flu or any other respiratory viral pathogen? Otherwise, I suspect there is more noise than signal.

Comments are closed.