Tyler Cowen has a new post that discusses the implications of under-measuring economic growth:

Many people suggest that we are under-measuring the benefits of innovation, and thus real rates of economic growth are much higher than we think. That in turn means the gdp deflator is off and real rates of interest are considerably higher than we think. Someday we will all realize the truth and asset prices will adjust.

Let’s say that view is correct (not my view, by the way), how should that change your investment decisions?

As with Tyler, that’s “not my view”. I don’t believe that growth is faster than we think. It will be easier to explain why when we consider the implications:

More generally, if real rates of return are high, but not perceived as high by most investors (who are still victims of fallacious “great stagnation” arguments and the like), at some point those investors will learn. With more rapid growth enriching the future, and with the realization of such, there will be a sudden demand to shift funds into the present, so as to equalize marginal utilities. So bond prices will fall and that means you should short bonds and buy puts on bonds.

Growth is getting increasingly hard to measure as we move from an economy of stuff (commodities) to an economy of intangibles. If we can no longer measure growth in terms of quantity of “widgets” being produced, we need some measure of the value provided by economic output. You could use money, but the value of money itself changes over time. So that won’t work.

Economists typical speak in terms of “utility”. But as far as I know there is not a shred of evidence that we have more utility than we had 60 years ago. When I look around, it doesn’t seem like people are happier than when I was a child. Maybe they are happier (I’m agnostic on the question), it just doesn’t seem that way to me. Of course utility and happiness are not necessarily the same thing, but I’d make the same argument for each. It’s not clear we are getting happier, and it’s equally unclear that we are accumulating more utility.

Now you might argue that this is because real wages have stagnated for 60 years. I don’t agree, but that argument cannot account for China, where polls show no aggregate increase in happiness since the 1990s. No one disputes that real wages in China (as conventionally measured) have soared much higher. Unlike Americans, the Chinese really do have lots more stuff; it’s not just quality change. So economic growth is a slippery concept, which is hard to measure.

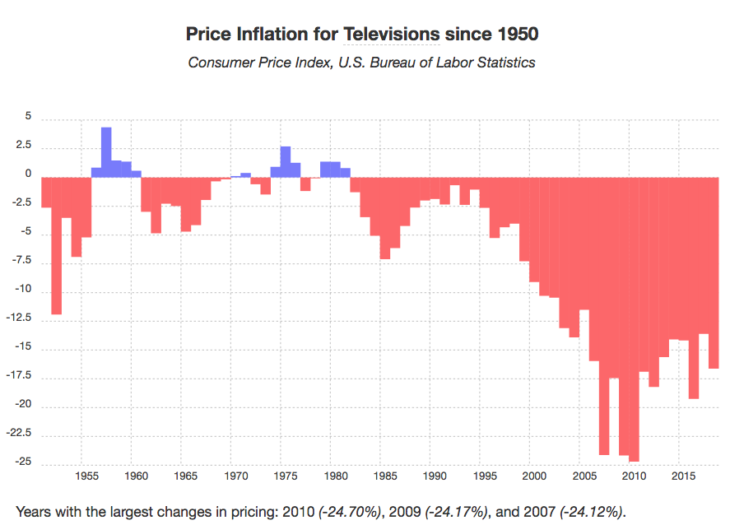

Here’s one simple example. A part of the measured growth in real income comes from the fact that the BLS considers our current TVs to be many times better than the TVs of 60 years ago. As a result, the BLS says that TV prices have fallen by roughly 98% since 1959. I certainly enjoy my new 77-inch OLED set. But it seems unlikely that the utility derived from these sets is 50 times higher than TV sets from 1959, at least if “utility” is defined the way I visualize the term. So “growth” is probably being overstated, if utility is what we are interested in.

If people really did perceive rapid growth in living standards, then they would want to shift consumption from the future to the present, as Tyler says. Yet polls show that people are increasingly pessimistic about their children’s economic prospects. I suspect they might be too pessimistic, nonetheless there doesn’t seem to be much of a perception that technology is producing rapid economic growth.

It’s almost like people treat technological progress as analogous to climate change—something in the backdrop of our lives. To most people, actual economic growth is something tangible and positional, like a better house and car. New products like iPhones and HDTVs are just “how we live today”. If boomer’s kids have to downsize from their parent’s 5 bedroom 3000 sq. foot home to a small three bedroom ranch, that’s perceived as going backwards, even if the smaller home is full of gadgets that they could only dream of back in the 1960s. And I’d say the same is true of lots of other changes. I consider restaurant food today to be vastly better than when I was younger, but replacing a steak and potato dinner with a $12 meal at a good Sichuan restaurant doesn’t seem at all like “economic growth”, as the 1959 “supper club” was viewed as in some sense more luxurious than is the modern Chinese place. This sort of evolution seems more like cultural change. The food tastes much better, but because of the hedonic treadmill it doesn’t make us happier.

I suppose it’s worth trying to measure economic growth, but don’t take the findings too seriously.

PS. If you did a survey of the public and asked them to estimate the current rate of inflation, I’d consider the poll results to be just as “scientific” an estimate of “actual inflation” as those produced by the BLS, or by academic economists who try to improve on the BLS data.

PPS. And I’d consider the poll results for the less educated half of the population to be more reliable than those for the more educated half, whose responses might be “contaminated” by having heard the most recent BLS inflation data reported on NPR.

READER COMMENTS

Dylan

Feb 10 2019 at 1:30pm

The hedonic treadmill question is interesting and, if true, probably requires a much more fundamental rethink of the tenets of modern economics than I have time for today. So instead I’m just going to focus on the TV part, which does seem to be one of those areas where I’m much happier than I was 20 years ago. But it isn’t the TVs themselves, instead it is the giant improvement in quality at the same time that real prices have fallen off a cliff. In 1999, cable TV cost $80 a month in nominal terms. That year the family got the newly released TiVo (we got a lifetime subscription, but IIRC, the monthly subscription was $10 a month). This made watching Cable TV a lot more bearable than it was the year before, I no longer had to make sure to be in front of the TV at a specific time, and I could fast forward through commercials. But still, the shows available to watch weren’t that great, I had to remember to record them, fast forward through commercials, etc.

But for the last 12 years I haven’t had to do any of that. For the $10 it cost for TiVo, I now have Netflix that gives me much better content than I ever had before, with no commercials, on demand, a full season at a time. My problem these days is trying to decide among hundreds of great options where not that long ago it was choosing among a couple of mediocre ones. I don’t know how to measure precisely the increase in my utility, but it feels pretty substantial.

Scott Sumner

Feb 10 2019 at 3:43pm

Does your current TV set provide 50 times as much utility as the ones from 60 years ago? I do like like the new set much more than the ones I watched as a kid, but 50 times more?

Dylan

Feb 10 2019 at 6:29pm

The TV itself, no. I’m not much a visual snob though, so things like HD do less for me than they seem to for the average person. I do appreciate that they are a lot smaller for the screen size than they used to be, use less energy, and of course are much, much cheaper. I am having trouble understanding exactly how the BLS measurement works, I do know that my family bought a 60″ TV for ~$6000 in the late 90’s, and a year and a half ago I bought a 50″ TV for $200. Yeah, the picture is a little smaller, but otherwise my new TV is better in every way than the old one, and cost 3% of what the old one cost before taking into account inflation over the period.

Then, when you pair the TV with the content available, it definitely provides a huge amount more utility than it used to. Again, I don’t know exactly how you would measure the increase, and it is particularly hard since at the same time as television quality has improved dramatically, so have many other types of free or cheap entertainment. Which means the increase strictly from my television watching isn’t as great, since I’ve got all sorts of substitutes I didn’t have 20 years ago.

Phoenix44

Feb 12 2019 at 11:32am

But general inflation doesn’t measure that, neither does general growth. Some people could not afford a (expensive) TV back then, now they have a wonderful one. That’s an infinite increase in utility. For me it’s maybe twenty times better. And of course it’s no longer a TV, so what am I measuring against anyway? That I no longer have to have a VCR and a library of tapes? That I don’t have to watch the ads? that I can record three programmes at once instead of one?

And perhaps we would be moving consumption to now – unless we were all living longer and hadn’t really saved for that. One of he big problems in the western World – demonstrated by pension deficits – is that the substantial increases in longevity took us all by surprise.

So I don’t buy your arguments fully.

Basil H

Feb 10 2019 at 2:24pm

Scott,

“But as far as I know there is not a shred of evidence that we have more utility than we had 60 years ago”

This is something you write a lot, but I really have to push back on this. Stevenson and Wolfers argue pretty convincingly, in my view, that empirically there’s a significant positive relationship between income and happiness: both (1) for a given country, over time; and (2) across countries, at a given time.

Paper; nice summary from WaPo (great graphs); EconTalk episode.

It’s totally possible this correlation has a reverse causation — I see you’ve argued this previously. Totally possible — and I definitely think that’s true to some extent.

But there’s at least some good quasi-experimental evidence that suggests that income causes happiness: evidence from lottery winners. Comparing lottery winners and non-winners, they find higher life satisfaction — which doesn’t dissipate with time! — for the winners.

A separate question is the quantitative impact of income on happiness. Maybe income is associated with higher happiness, but the slope is very flat. Possible! And Stevenson-Wolfers certainly find diminishing marginal utility.

—

On the other hand, for the sake of transparency, I will say that the “habit formation” explanation for the equity premium puzzle provides evidence for your model of “hedonic adaptation.” Paper 1, paper 2, blog.

(However there are of course many alternative explanations for the equity premium puzzle that do not assume/result in “hedonic adaptation”.)

Scott Sumner

Feb 11 2019 at 1:50pm

I am relying on memory, but I believe their results are based on survey data. I also believe that survey data does not show an increase in American happiness. Am I wrong?

They do find a cross sectional correlation, but that doesn’t tell us what happens within a given country when incomes rise.

Basil H

Feb 11 2019 at 2:06pm

1. It is based on survey data, yes — but how else would you empirically measure life satisfaction?

2. They find both cross-sectional and timeseries correlation, to be clear.

3. Yes, this is very much correlation not causation. But that’s why I find the quasi-experimental evidence we do have so important (i.e. the evidence from lottery winners)

4. Eyeballing Figure 12 in the paper, it looks very much to me like Stevenson-Wolfers find a positive relationship in the US timeseries.

Scott Sumner

Feb 12 2019 at 1:26am

Just to be clear, I definitely agree that richer people tend to be happier (in cross sectional data), for all sorts of reasons. I wasn’t able to find the Figure 12 you referred to, do you have a link?

I recall reading that survey data did not show an increase over time in American happiness. That may be wrong, but it fits in with what I observe—people I meet in my daily life just don’t seem happier to me, or at least not dramatically so.

Even if lottery winners are happier, it may reflect a relative wealth effect, and not tell us much about what happens when we all get gradually richer.

David S

Feb 15 2019 at 5:44pm

I think the pertinent question may be: “How much would I have to pay you to live in 1960?”

Replace with your favorite date, 1910, 1860, etc. It might be difficult to put a number on a recent date: for example I was alive and relying on my parents in 1990, so life was good! It might at least set the overall trajectory.

I don’t think there is enough money in the world for me to live in the 1200s, for example. So growth since then is infinite, from my perspective!

Robert EV

Feb 17 2019 at 9:28pm

@David S

How much would you pay to live in the 2200s? Keep in mind that you’d be hopelessly incompetent and totally out of your comfort zone even when it comes to typical living requirements, and wouldn’t have any resources to live then anyway, especially as you just paid someone to live then.

Visiting the time period would be great, but the same could be said about visiting the 1200s.

Living then is a totally separate issue.

Daniel Carroll

Feb 10 2019 at 3:23pm

It seems we often confuse status (relative well being) with absolute well being. People are much happier if they are the wealthiest in a poor neighborhood rather than the poorest in a wealthy neighborhood. People measure their progress by benchmarking others. So if utility is defined in terms of happiness, then it is a zero sum game, and there is no improvement over time. Indeed, I suspect 90% of our political disagreements boil down to how to divide up status points.

Cliff

Feb 11 2019 at 1:27pm

“People are much happier if they are the wealthiest in a poor neighborhood rather than the poorest in a wealthy neighborhood. ”

Are there studies? I would MUCH prefer the latter. Being around poor people is awkward because you don’t want to feel like you’re bragging, plus poor people have different cultures/interests and on average are more dangerous, less intelligent, etc. (there are plenty of nice poor people and plenty of rich jerks no doubt, but on average).

Culturally I would fit in much better with the rich people and they would probably throw off nice benefits like really nice parties, etc. I have everything I need so it would be little different than if I was a billionaire but just living like Warren Buffet, very frugally.

Tom West

Feb 17 2019 at 3:08pm

Personally, I find people seem to be happiest being just a bit better off than their peers. Enough to feel successful, but not enough to start alienating those peers (or feeling guilty about one’s success).

David Henderson

Feb 10 2019 at 3:55pm

Scott,

I don’t think you’ve established that you have to think you get 50 times as much utility from a TV now as you got then in order to say that the CPI overstates inflation. Is the BLS saying, or implicitly implying that 50 times number?

Scott Sumner

Feb 10 2019 at 5:02pm

David, If the BLS is telling us that the price of TVs has fallen by 98% since 1959, and the nominal price of the average set being purchased has hardly fallen at all (say around $100 or $200), then how else can I interpret the data? The assumed fall in TV prices must be almost entirely driven by assumed quality increases.

Gordon

Feb 10 2019 at 5:56pm

Does the BLS measure price changes on TVs by the typical TV consumers buy in a given year? Or does the BLS measure the price changes by comparing TVs of the same size? A 23 inch color TV 50 years ago cost about 4.1% of the median nominal family income back then. A 23 inch TV today costs .13% of the median nominal family income. And for today’s TV, you’re not going to have to call someone for repairs or take the vacuum tubes out so you can check them on the tube tester at the grocery store.

Mark Bahner

Feb 12 2019 at 4:03pm

We need to bring that back! Surely that’s part of MAGA! 😉

MarkW

Feb 10 2019 at 7:14pm

But as far as I know there is not a shred of evidence that we have more utility than we had 60 years ago.

What sort of measure would you accept? Most happiness surveys ask for 1-10 ratings, which put an artificial cap on increases. Imagine asking people for 1-10 ratings on their income and then using those survey results to determine there had been no increases in 60 years. If we want to see absolute increases in utility/well-being, we’re going to need an absolute rather than relative measures.

I’m not quite old enough to compare now to 60 years ago, but I can think of dozens of ways utility has increased compared to when I was a kid in the 60s and 70s. When it comes to TV, it’s not just the device that’s gotten dramatically cheaper and better, it’s the content — hell, even video rental stores were an unbelievable boon compared to being stuck watching whatever network dreck was on that night.

Scott Sumner

Feb 11 2019 at 1:48pm

Mark, I agree we have lots of improvements, I just don’t see it making us happier. I’m much richer than I used to be, but no happier.

Benjamin Cole

Feb 10 2019 at 7:27pm

In many regards living standards in the United States are falling.

A friend of mine grew up in Los Angeles, went to public schools, he is about 70 now. He went to UCLA (almost for free). He started a small financial business and was successful.

In normal course he had started a family. But he felt he had to send his children to private schools in order to remain competitive within their cohorts. Ultimately he ended sending his sons all the way through Northwestern MBA programs. We are talking about 18 years of private schooling per son.

Even so, it is unlikely his sons will be able to replicate his lifestyle of a pleasant large home in West Los Angeles.

I read that wages for young Americans are about 75% of 1972 levels.

By the way, Japan apparently has sidestepped these problems of urbanization. Younger Japanese are again seeing real wage increases, due in part to tight labor markets. Tokyo is regarded as one of the most livable large cities in the world, in part due to modest housing costs ( Japan allows property development).

There is the lugubrious prospect that American macroeconomists have been wrong on nearly every major issue within their craft for a generation or two.

Tight money is a disaster. Open borders results in lower living standards, if property development is restricted. Large current account trade deficits leads to bloated asset values, including housing .

If you are young you want to live in Tokyo, not Los Angeles.

ChrisA

Feb 10 2019 at 11:37pm

Ben – someone will live in that large comfortable home in West LA, and someone will go to UCLA. Maybe it’s not your friends son, but we should look at overall living standards, not just one or two cases. In my opinion for every person like your friend’s son, who has seen his standard of living (possibly) fall, there are probably tens times the number of people who have achieved a better standard of living than their parents.

MarkW

Feb 11 2019 at 10:20am

Successful people often have kids who don’t do quite as well. Many of my aunt and uncle’s neighbors in their high-end Florida retirement community seem worried that their kids aren’t doing as well as they did. They think this is evidence that the country is going down the tubes, but all it really represents is reversion to the mean.

Mark Bahner

Feb 12 2019 at 4:10pm

Yes, look at Bill Gates Sr. 😉

Brian

Feb 11 2019 at 7:59pm

I do not think it makes sense to suggest that if your friend’s son will find it difficult to buy a house in West LA for what it cost in, say, 1975, (expressed as a multiple of income) that living standards have decreased.

It would make more sense to look at the economic opportunities within 30 minutes driving distance of West LA in 1975 and compare that to the economic opportunities within 30 minutes of a different city in 2019. As the U.S. population has grown over the years, surely there are many places that present that level of opportunity.

If you are not destined to be in the entertainment or media industries then West LA real estate loses much of its appeal as an asset. Some things have a property of being a rare asset obvious only after the fact.

Thaomas

Feb 14 2019 at 1:23pm

Agree that property development is a drag on the growth that increased immigration would produce, but would it absolutely make immigration damaging? How does that work?

Of course the tight money (partly excessive fear of inflation and partly reaction to structural fiscal deficits) is the explanation of the trade deficits. How do these lead to “bloated” asset values?

Mark Z

Feb 10 2019 at 9:28pm

I think you’re ignoring that products may become more valueable in ‘real’ terms without improving in quality. Just owning a TV in 2019 is much more useful that in in 1959. There are many more shows and movies one can watch, so while the quality may not increase much, the TV is a conduit to obtaining more value than it was 60 years ago. Also, people have more leizure time today, allowing them to watch more TV, increasing the amount of utility they get out of it. Americans spend almost twice as much time watching TV as they did 60 years ago (I did a quick google images search and got a graph roughly over this time from the Conversible Economist: http://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2012/10/time-watching-television.html).

“But as far as I know there is not a shred of evidence that we have more utility than we had 60 years ago.”

There’s an abundance of evidence that we have more utility than we did 60 years ago. Are migration rates from the US to countries with living standards more comparable to US living standards 60 years ago about the same as migration rates in the opposite direction? Do you think most Americans would happily pay 1959 prices for 1959 quality healthcare? Why has the suicide rate remained stable or even declined slightly even as life expectancy has increased dramatically (suicide rates are much higher among older people than younger)? Even the decline in violence and generally dangerous, risk-seeking behavior can likely be attributed at least in part to people valuing their lives more. Looking at revealed preferences suggests to me considerably more utility today.

Scott Sumner

Feb 11 2019 at 1:53pm

Mark, None of that evidence contradicts my claim if we are on a hedonic treadmill. I don’t dispute that we have better stuff, and that we prefer better stuff (revealed preference). I dispute that it’s possible to measure how much happier we are, or how much more utility we have. Those concepts can’t even be defined properly.

Mark Z

Feb 11 2019 at 3:51pm

Not being able to effectively measure a variable (I’d agree that it’s very difficult to measure relative happiness, certainly with surveys, though I think revealed preferences like suicide rates, risk-taking, and migration patterns can be informative) doesn’t imply that it’s static.

Scott Sumner

Feb 11 2019 at 4:11pm

I agree. Thanks why I said I’m agnostic on the question.

Ken P

Feb 11 2019 at 12:50am

A 40inch flat screen is $150 at Walmart. In 2001 42 inch plasmas were going for over $12000 with a much lower quality picture. So on high end it’s pretty close.

Scott Sumner

Feb 11 2019 at 1:56pm

Ken, That’s exactly my point, those comparisons are meaningless. Back in 2001, people didn’t spend $12000 on TVs. They spent a few hundred bucks. And they enjoyed their TVs almost as much as they enjoy their current TVs, which also cost a few hundred bucks.

Aleksander

Feb 11 2019 at 1:01am

It might be easier to imagine what those numbers mean if you ask yourself “Can I buy a 1959 TV for 2% the price of a modern TV?”; and more importantly, “Would I buy a 1959 TV for that price if I could? (If I can, why don’t I?)”; or even, “Would a rich person in 1959 pay 50 times the value of contemporary TVs for a modern TV?”.

There are some conceptual complications here, so we can’t expect the answer to each of these question to be perfectly mathematically compatible with each other and the inflation index. But I actually wouldn’t be surprised if most of them land in roughly the same ballpark.

Ognian Davchev

Feb 11 2019 at 3:34am

If you imagine having both a 1959 TV set and a modern one at home how often would you choose to watch the old set? I think for most people it would be 1 in 100 or even 1 in 1000 in favour of the modern set. It’s not hard to imagine that the new one is 50 times better.

Scott Sumner

Feb 11 2019 at 1:58pm

I used to watch the old sets, and while I’d pay 50 times more for a modern set, I don’t even get twice the utility. That’s my point.

Mark Z

Feb 11 2019 at 3:57pm

So, you’re willing to pay 50X as much, but it doesn’t give you 50X as much utility. I think the conclusion warranted from this is more modest than what you’re concluding regarding hedonic treadmills or inflation: that prices and utility just aren’t necessarily linearly related. And we probably shouldn’t expect them to be, given the law of diminishing marginal utility.

Scott Sumner

Feb 11 2019 at 4:13pm

I never concluded we were on a hedonic treadmill because of extra TV utility being modest, my hedonic treadmill perception is based on the fact that people don’t seem to be getting happier in any overall sense. I am not confident in that claim, rather it’s my best guess.

Jim Birch

Feb 11 2019 at 7:23pm

Happiness might not be the right measure. Happiness is probably more related to stress levels than product ownership. For pretty good evolutionary reasons, people are wired to bump up their stress levels to where they start to feel unhappy. It may be unrealistic to expect products to bring happiness but they may bring some other kind of enrichment. (Either that or we should all become Buddhists, but we can’t.)

J Mann

Feb 14 2019 at 12:31pm

Can anyone recommend some reading on this point? I don’t even understand what that means, which is very likely my failing.

If I buy a piece of fruit every day at a store that only sells apples, and I am indifferent between paying $10 for an orange and $2 for an apple, doesn’t that mean the orange gives me as much utility than a bundle of an apple + $8?

If the store switches from apples to oranges and still charges the same price, I think I’m $8 better off.

If I say “I’d prefer to pay $10 for an orange rather than $2 for an apple, but I don’t get even twice the utility from having an orange instead of an apple”, I’m not even sure what that means.

Again, it’s probably me – if anyone can recommend some remedial utility readings, I’d be grateful.

Alan Goldhammer

Feb 11 2019 at 7:44am

IMO, discussing the cost of televisions is the wrong approach. For me it is available content (the same thing goes for my Android phone). I have a computer driving my televison (32 inch Sony and I really don’t need a bigger screen as my viewing room isn’t all that big. I can watch normal television channels using a cable card tuner that let’s me avoid paying Verizon for a set top box (savings is $15/month) or I can stream Netflix, Amazon Prime, and ESPN+ (which has great content for only $5/month). the only sports that I watch are Euro soccer matches and I have a great selection every weekend. None of this was around even 10 or so years ago.

Scott Sumner

Feb 11 2019 at 1:59pm

Alan, I agree we have much better stuff, but is it making us happier? And how can we possibly measure how much better the new stuff is?

Alan Goldhammer

Feb 11 2019 at 4:24pm

For me it’s pretty simple. I can watch high quality ESPN+ streams of my favorite soccer team, Ajax, every weekend! I have very simple needs. 🙂

Andrew_FL

Feb 11 2019 at 9:40am

Or, maybe the reason it doesn’t seem like people get more utility these days than in the past is because you can’t make interpersonal utility comparisons.

Scott Sumner

Feb 11 2019 at 1:59pm

Yes, and maybe it’s because they aren’t happier. That’s how it seems to me.

art andreassen

Feb 11 2019 at 10:28am

Scott: The BLS says the real price of a TV is 50 times more than the nominal price and this index is used to raise real output. My problem is, nowhere does BEA or BLS specifically raise any real input 50 times to balance the real input side of the accounts. I know income and output balance at the end in the accounts but that is accomplished by scaling the real income side to balance to the real output side. I think more has to be done to balance the input side. Telling workers their income had risen when they see no proof in their wallet leaves something to be desired.

Ted Craig

Feb 11 2019 at 1:12pm

On the matter of TVs, I think you have to look at it as a bundle of equipment and services. There is no question the utility has increased. In 1959, you has access to half a dozen channels, at most, depending on where you lived. Today, we have access to an infinite amount of choices. But those choices come at a cost. Even the $10 or so for a streaming service is $10 more than people paid for TV programs in 1959.

Of course, you can use the TV to play video games, so there is even more utility, but this also adds to a cost.

If you measure it as paying for an activity (watching TV) rather than paying for a product (the TV itself), it seems the decrease in price is less than 98 percent.

Scott Sumner

Feb 11 2019 at 2:01pm

Ted, I agree they are much better, but I’d guess it makes us 50% or 100% happier watching and playing, not 50 times happier.

J Mann

Feb 14 2019 at 11:06am

Multiples of happiness definitely aren’t the right measure. If I buy a $20 bottle of wine instead of a $10 bottle, I don’t expect the fancy wine to make me twice as happy as the basic bottle.

I *do* expect the fancy bottle to make me at least as happy as two basic bottles, of course. And I expect a 2019 TV to make me happier than 50 1959 TVs, but that isn’t really the whole question.

I guess the bottom line is that expect the fancy bottle to make me happier than a package of the basic bottle plus any other use of the additional $10. Is it possible to do that comparison when we compare the 1959 goods and 2019?

I’ll think about.

J Mann

Feb 14 2019 at 12:02pm

Scott, thinking about this a little more, I think my proposed measure of comparable utility might be the right one, and that it probably support the BLS estimate.

Let’s suppose you bought your 77″ TV for $6,500. Isn’t the relative value question what you you (or an average shopper, maybe), would have done if you had two choices for a TV when you went to the store: (1) a 77″ 2019 TV for $6,500, or (2) a 1959 TV for $130? I don’t think most mega TV buyers would prefer the 1959 TV, even at that price.

Similarly, I have a 37″ TV that sells for $180 in 2019. If I went on Amazon and was offered that or a 1959 TV for $3.60, I would still choose my current TV. Doesn’t that mean the modern TV is “worth” at least 50 times as much to me as the 1959 TV?

I haven’t thought about this before, and would be interested in anyone’s comments.

Stipulations: I think it makes the comparison more fair to assume: (a) it is possible to repair the 1959 TV at the same fraction of its price as it would have cost to repair in 1959 and subsequent years, (b) I am actually purchasing the TV to use as a TV, and not as a conversation piece or collector’s item, and (c) further to (b) the 1959 TV can receive current television content – cable, broadcast, dish, etc. (I’m not sure what the best assumption would be about compatibility with computers etc., but don’t think it’s material).

Michael Sandifer

Feb 11 2019 at 1:29pm

It seems that in an economy in monetary equilibrium, and that does not have government debt financing problems, interest rates on government debt should converge with NGDP growth expectations. Otherwise, in absence of relatively high government default risk, longer term interest rates below central bank NGDP growth forecasts should be a sign that money is too tight, and hence potential GDP is higher than recognized.

That’s one reason, among others, why I think potential real GDP is underestimated, even though said metric is hard to measure.

ChrisA

Feb 11 2019 at 1:30pm

Not mentioned by Scott or other commentators is the problem of new products for inflation calculating (and corresponding growth measurement). Maybe this is what people like me (who don’t buy the stagnation thesis) are referring to when we say growth is higher (and inflation is lower) than it seems. Smart phones for instance were not even in the consumption basket in 1990’s, so their appearance in say 2005 from not existing to existing was a big change in absolute growth. At some point, once enough people had I-phones, we started to measure the cost reduction or make assessment of quality improvements but that was after the big growth had occurred.

From a retirement point of view, this affects how much money I have to save. If I just look at the existing goods basket then I can confidently think that prices for things like smart phones and TVs, will continue to go down. So maybe I don’t need so much money saved and I can spend more today (which I guess is what Tyler is referring to). But if I allow for the fact that there will be new goods and services introduced that I will want to buy, then I need to save for those as well. The classic example of this is medical services – I can expect that there will be lower costs in the future for current 2019 medicine as things like patents expire, and more doctors learn current techniques. But I am sure I am going to want to consume some of the future medical technologies that are yet to be invented.

So contra Tyler – I don’t think more rapid growth than previously realised will result in lower bond prices or less saving, it could actually mean more saving. I think this is exactly when many people mean when they say that the cost of living is rising more rapidly than the official figures represent – the cost of living is rising because there is more to buy (even if individual items are cheaper).

Brian

Feb 11 2019 at 1:41pm

This is probably a naive question, but I don’t know the answer, so here goes:

Why not measure economic growth in whole or in part as the amount of work we humans get other “stuff” to do for us? Firewood and animals did (and still do) some amount of work keeping us warm and increasing labor inputs for agriculture, etc. Now we also have car engines, power plants and much else producing energy for some sort of work that would otherwise require human labor. And we have transistors as an approximation for mental work of some sort. Presumably energy produced to displace manual labor and manual thinking is being produced in response to economic demand. Why not measure this? How many transistors were in a 1950s era TV vs a modern TV?

This plot of number of transistors produced per person is pretty amazing:

https://www.darrinqualman.com/global-production-transistors/

There is clearly a lot of growth in transistor production in response to a lot of demand over the course of the so-called great stagnation. The amount of “manual” work done via energy generation of some sort or other depends on the efficiency of the thing being driven by that energy. Same with transistors: chip architecture and the software that runs on it can be more or less efficient. But in general, efficiencies improve over time. So the growth in the amount of energy we produce and the number of transistors produced would seem to be at least a conservative estimate economic growth? How well this translates to dollars seems sort of arbitrary, as the dollar itself seems sort of arbitrary.

Bryan Willman

Feb 11 2019 at 1:42pm

First, I think “happiness” is a useless measure, because it is surely evolved to be a moving target. A mid-20th century philosopher whose name I cannot find, observed we get bored when we’re not active enough in pursuing goals, stressed when we are too active. I think happiness is the same – if we’re “doing well” on our self perceived status, “doing well” on our self evaluated evolutionary metric, we’ll feel happy. Whether our objective circumstances are better, or just less awful, may not affect it at all over time.

Second, sometimes things have huge utility, but it comes mostly in big globs, not in 1.4% per year patterns. I happen to have an artificial knee. It is stunningly good. What would a 1955 or even 1985 person with horrid osteoarthritus have paid for it? A LOT. On the other hand, the vast content of the web means I don’ t have to watch TV anymore, at all. I am TV free. I pay nothing for this. What is its utility to me? QUITE HIGH – I generally hate “TV”.

But awesome treatment for bad knees, or replacement of 3 crappy channels with The Web, are not things that happened at 3% per year.

Third, and most important, there are utility ceilings. Time, as in 24 hours per day for everybody, is one very hard one. Yes, life extension can offer more days, and that surely has huge “utility”. But if there’s more than 24 hours of 1st rate material produced every day (there is) I cannot possibly consume it.

Once every person’s utility, either in work they enjoy or consumption, has filled their waking hours, per capita utility cannot grow past that point.

IVV

Feb 11 2019 at 2:06pm

How much would it cost to live like it’s 1959 today? By which I mean we can use today’s technology, but only deliver 1959 levels of product and service? So, for the TV example, it could be delivered like Netflix, but only with the level of a few preset black-and-white low-def channels, and between that, radio, and the landlines, is the total extent of broadband delivery to the home?

Walter Antoniotti

Feb 11 2019 at 2:56pm

I am 75 and spend all of my time enjoying products that were not only not available to my dad 30 years ago, most of them lower GDP. How can a system based on efficiency measure growth based on price. Make it better, cheaper, and GDP goes down. I taught Econ in 1966 with McConnell’s first econ textbooks. Most changes since then are not correct!

P Burgos

Feb 11 2019 at 3:44pm

I guess I would be satisfied with trying to side-step some of these utility questions by looking at a basket of goods including housing adjusted for sqft., costs of electricity, water, natural gas, and other utilities, transportation, child-care and public education, college tuition, cost of access to basic medical care, food, furniture, clothing, etc. That is, just focus on the basic goods and services, education, and healthcare, and don’t even worry too much about utility or quality adjustments. Just ask if people find it easier to afford to put a roof over their heads, heat the place and pay for utilities, buy clothing, get to and from work and the store, visit a doctor, send their kids to school and university, and afford basic furnishings for their abode. If people have to work fewer hours to afford those things, living standards are rising. If people have to work more hours to afford those things, living standards are falling.

Lee A. Arnold

Feb 11 2019 at 4:13pm

Well if somebody was happy all the time 50 years ago, then anyone who is happy all the time today cannot have more utility. There are only so many hours in the day to be happy. If utility means satisfaction, the same applies.

More seriously, as soon as we start admitting benefits of innovation that are unmeasurable or poorly measurable, such as the benefits of IT and social media etc, then there is no reason not to consider government institutions as ALSO increasing economic value, e.g. good transfers or regulations can work like a non-rival good to provide unmeasurable growth in positive externalities, or else to provide unmeasurable savings from negative externalities — particularly in the arenas of quality of life and environment. And I think we should do this, really. But it means that the wheels are going to start coming off market economics, in favor of a broader understanding of unmeasurable increasing returns across many levels of society.

Scott Sumner

Feb 12 2019 at 6:11pm

Lee, I believe that market economies make people happier by encouraging them to treat their fellow man better.

Tiago

Feb 11 2019 at 4:31pm

Good post. Worth considering this evidence, however, specifically related to China:

“In recent decades, China’s suicide rate has declined more rapidly than any other country’s. It has fallen from among the world’s highest rates in the 1990s, to among the lowest – below the US and only slightly higher than the UK.”

https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/remarkable-fall-chinas-suicide-rate

Scott Sumner

Feb 12 2019 at 1:29am

Tiago, Good point, and I am skeptical of survey data on happiness. But if the survey data is wrong, what evidence do we have beyond common sense?

Tiago

Feb 12 2019 at 10:18am

My reasoning was that suicides are a form of “revealed preference” on life conditions, so they should count as evidence. Given the size of the consequences, they are very powerful. Surveys always suffer from the “cheap talk” problem. Naturally, we do not always have statistics such as these on suicide available. Small improvements in well-being would have a very small effect on that. But in this case, we do, and I would assign more weight to the suicide statistics, also because it fits better with all the evidence that life conditions are indeed improving in China.

Scott Sumner

Feb 12 2019 at 6:12pm

I see. Are suicides increasing in the US?

Howard

Feb 11 2019 at 7:18pm

Do we have more utility today than 60 years ago? I’ve always thought of this in terms of revealed preference: in my childhood, for example, my (upper middle class family) had one (un-airconditioned, no sound system) car, one black and white TV with four channels, we ate out very infrequently (on highway summer trips to visit grandparents), and we lived in a two parent, one-income household with a parent at home to fix meals, clean the house, care for the children.

I can’t prove this, but I think that many households could re-create this 60 year old lifestyle in the current economy, and could do so with money left over. (So, if I’m not being clear: one parent stays at home, eliminate childcare, eliminate food away from home, eliminate cable, cellphone, eliminate travel abroad, eliminate second, third cars, blah blah you get the point — and you’ll have more savings than you have with current modern lifestyle.)

So (revealed preference) you prefer current modern lifestyle to 60 years old lifestyle, when both are feasible; conclusion utility is higher with current modern lifestyle.

Scott Sumner

Feb 12 2019 at 6:14pm

That comparison doesn’t work, as the happiness from a given lifestyle depends on whether your neighbors have a much better lifestyle.

Brian

Feb 11 2019 at 8:45pm

I do not believe we are supposed to compare the 1959 price of a product to the 2019 price of a product.

The reason we should not do this is because the product is changing.

Suppose the TV inflation series is based on 10 samples. Suppose in the year 2002 we get the prices of 10 typical TVs. Suppose in 2003 we find that only 6 of the 10 are still made. So we can take 4 new products available in 2003 and look at their characteristics and find 4 products from 2002 with similar characteristics. So the average feature set of the product is changing. This is almost harmless between 2002 and 2003 for the purpose of measuring the average price change.

Another way to do it is to write down the list of features people care about and find those features in 2002 and find the same features in 2003 and compare prices. Each year we can re-write the list of features that people care about and as long as we do not change it dramatically it is almost harmless.

Both of these methods are impossible between 1959 and 2019 because the products are very dissimilar and the features valued or appreciated by consumers are very dissimilar. 100 inch TVs did not exist in 1959 because nature abhors a vacuum and a 100 inch vacuum is very abhorrent.

Thanks to arithmetic and spreadsheets we can compound several one year inflation rates to figure out what happened to the price between 1959 and 2019 but just because you can do this does not mean that you should.

Since we are not supposed to compare the 1959 price to the 2019 price we have no basis to make a claim about the change in utility of that product.

Christian List

Feb 11 2019 at 9:07pm

I do not understand why NGDP (or real GDP) should not be enough. Sure, it’s (like most things) not always 100% accurate, but it’s accurate enough.

Brian

Feb 11 2019 at 9:33pm

I agree, real GDP per capita is good enough as a measure of quality of life from one year to the next. Just don’t compound them from 1959 to 2019. Please see my comment above about arithmetic and spreadsheets.

Todd Kreider

Feb 12 2019 at 1:18am

Yep. I haven’t had a TV since 2003.

Scott Sumner

Feb 12 2019 at 1:31am

Should you be banned?

Bryan Willman

Feb 12 2019 at 2:43pm

replying to @Howard’s and other’s thoughts “what does it cost to live a 1950s lifestyle today?”

For many people probably literally impossible. Because of employers who only accept applications via the web. Important groups that insist you have a smartphone. Lots of places you cannot buy parking with cash anymore, have to have credit card or an app on your phone. By the way your 1950’s car is illegal to make or sell new now, and some “luxuries” like power windows arise partly out of safety issues (no more window cranks to bounce off in a collision…) The poor B&W TV you lived with was financed by ads, and could not possibly support any revenue that way now, so its basically full color or nothing.

Depending on where your dwelling is, the local authorities may be requiring it to have sprinkler systems for fire protection. Many places require the septic system to be hooked up to a public sanitary sewer – you don’t get a choice.

In short, the *option* to do it a cheaper older way will often evaporate, at least for participants in mainstream society. Because the old ways are hopelessly unproductive (for somebody) or hopelessly expensive (to produce) than the new ways.

Todd Kreider

Feb 12 2019 at 3:01pm

How are the health pills going to be measured? NR and NMN cost around $1 o $2 a day.

David Sinclair, who is researching NMN, said a few weeks ago:

I interpreted that statement to be that in a year from now, it will be obvious how beneficial NMN and NR are to not only the elderly but to the middle aged as well in many health areas. Based on trials, this looks right.

The health pills will lower health care costs and increase the GDP by the price of the supplements times the millions of users there will eventually be each year.

Mark Bahner

Feb 12 2019 at 4:35pm

Hi Scott,

Let’s say sometime in the next 30-60 years no one in the U.S. has to work a day in their life in order to live at the median lifestyle of today (i.e., same amount and quality of food, clothes, housing, healthcare, etc.).

If that happened, what would you say about economic growth in the U.S. between now and that time?

Best wishes,

Mark

Scott Sumner

Feb 12 2019 at 6:16pm

Mark, I’d say that real income is higher, but I have no idea by how much.

Todd Kreider

Feb 12 2019 at 8:25pm

If I’m reading the question correctly, then the median income wouldn’t rise at all but leisure time would be way higher.

Mark Bahner

Feb 13 2019 at 12:45am

Yes, leisure time is essentially 100 percent, as long as a person would accept the median present values for amount and quality of food, clothes, housing, healthcare, etc. Seems like a very sweet deal to me.

Mark Bahner

Feb 12 2019 at 11:37pm

Hasn’t the utility gone through the roof? If everyone never had to work a single hour in their entire life to still have a pretty good life?

There’s a lot of talk about a “living wage” today. But that’s when people actually have to work…maybe 1900+ hours a year to earn that “living wage.” And presumably the median values for food, clothes, housing, healthcare today are above what could be provided by earning the “living wage.” In my hypothetical, all that is given without anyone having to work a single year in their lives.

Tony Hua

Feb 12 2019 at 6:42pm

What if we took happiness to be reflective of utility? So in other words, what are the mechanisms that drive the hedonic treadmill? For this, I turn to the concept of positional goods, and I would argue that future goods are inherently positional. That is, the invention of new goods and services inherently lowers the utility of older, existing goods. Someone in 1959 with a 1959 TV is happy with his purchase because there is no realistic “better” option. The development of newer TVs will reduce the utility of his TV. For a modern take, this drives a lot of the consumerism around new models of smartphones. Is the new model iPhone’s utility that much greater than the previous model that it’s worth spending $1000?

Now there are probably certain goods and services that are not inherently positional (or maybe less so others). Healthcare and medicine that improve life expectancy is a boon. Surely people who in 2019 who see their friends and family living longer are more grateful and happy about this outcome than someone in 1959 who saw close ones suffer and die from a variety of ailments that modern medicine has since cured.

Garrett MacDonald

Feb 12 2019 at 6:55pm

Eric Falkenstein has written a lot about relative utility and the Easterlin paradox.

J Mann

Feb 14 2019 at 10:57am

Does it matter which way you measure the change? I don’t think moving from 1959 TV to 2018 TV would give me 50 times more utility, but I think it’s possible that moving from 2018 TV to 1959 would cut my utility by 50 times. (Well, I’d move to a substitute, but let’s assume I watch the same amount of TV).

J Mann

Feb 14 2019 at 12:17pm

Update – in my replies upthread, I’m pretty close to convincing myself that if anything, a modern TV gives more than 50 times the utility of a 1959 TV.

My primary TV costs $180. I would strongly prefer it to a bundle of a (1959 TV + $176.40), if we assume that I’m actually going to be watching TV on it and not reselling it on the collector’s market or something. (And with generous assumptions on the ability to repair the TV).

Doesn’t that mean that a modern TV has more than 50 times the utility of a 1959 TV for me?

Seppo

Feb 14 2019 at 2:36pm

Any economist who really wants to measure ”happiness”, would do well by reading psychology, psychiatric and neurologic books. These brain sciences are the fields that can actually describe happiness as a phenomena and might help to explain lot of the unexplained results from economic research.

Mike Davis

Feb 15 2019 at 11:30am

Those of us who teach macro tell our students (or at least we should tell our students) that real GDP is a horrible measure of well-being–there’s the diamond-water paradox, non-market production, externalities and so forth. This means asking questions about how well measured growth in real GDP correlates to utility or happiness is to walk into the world’s craziest fun-house, full of slanted floors and curved mirrors.

Still, it’s an entertaining game to play and so here’s my take on why the BLS may be more or less right about TV’s. The “price of a TV” really obscures what we’re trying to measure, which is the price of particular unit of entertainment. We now own a nice flat screen, a surround sound system with decent speakers and all the usual subscriptions. That means that our movie-watching experience at home is a perfect substitute for going to the theater. (I know, that probably says horrible things about my aesthetic sensibilities, but don’t hate me.) In the pre-TV days we paid about $100 for a movie (2 tickets, 2 beers, 1 popcorn and 1 babysitter). I’m not quite certain how to measure the capital cost of the tv and Net Flix subscription but I’m pretty sure the cost of the movie now is less than $5 (the kid goes to be early and we drink cheap beer at home). Since the BEA doesn’t try to capture a “unit of entertainment”, maybe just lowering the price of a modern TV by 98% is the next best thing they can do.

Todd Kreider

Feb 16 2019 at 12:41pm

GDP was never intended as a measure of well-being, but it is not a horrible approximation of how well-off a country is, on average, materially. It doesn’t get at the number of hours worked or distribution.

Comments are closed.