We don’t know the precise natural rate of unemployment, but according to most estimates the natural rate has fallen from roughly 5%-6% during the 1980s to below 4% today. In Germany, the natural rate has fallen much more dramatically.

We also don’t know all of the reasons for this decline. Perhaps the rise of the “gig economy” has made it easier for the unemployed to find jobs.

The Wall Street Journal suggests another possible factor:

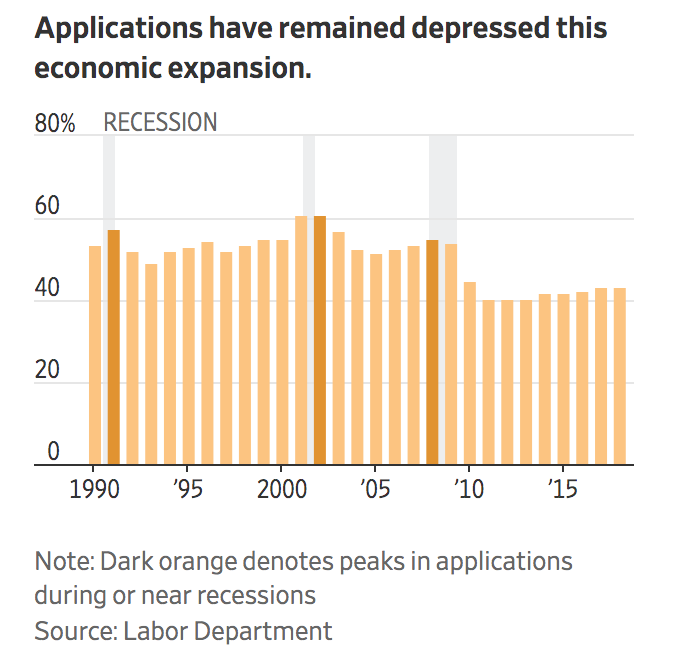

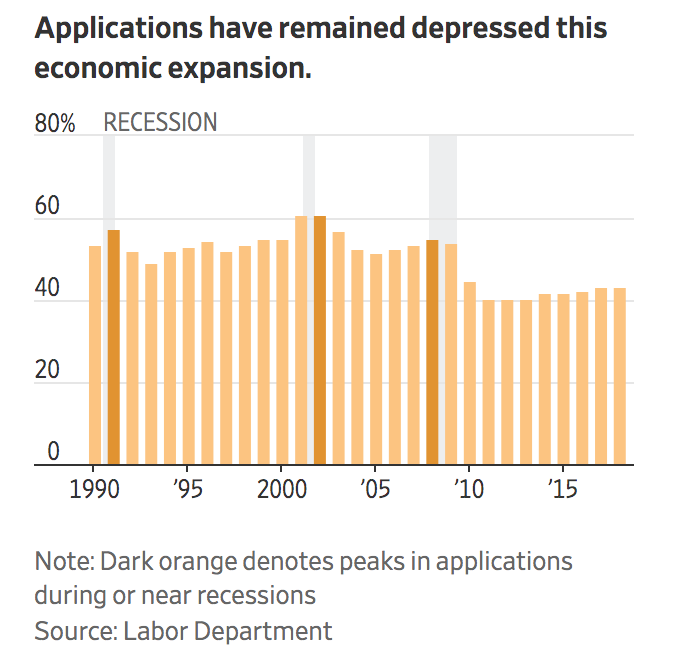

The share of jobless people receiving unemployment benefits fell after the 2007-09 recession and has stagnated at a historically low level since. Last year, 28% of jobless people received benefits, down from 37% in 2000—a period of similarly low unemployment.

Among the main reasons, experts say: After the last recession ended, state legislatures passed policies reducing unemployment benefits and tightening eligibility requirements.

They also provide a chart:

In 2014, Congress cut back on federal unemployment benefits. Some Keynesians argued that this would reduce aggregate demand and therefore slow job growth. In April 2014, Paul Krugman criticized the view that lower benefits would boost employment:

Ben Casselman points out that we’ve had a sort of natural experiment in the alleged effects of unemployment benefits in reducing employment. Extended benefits were cancelled at the beginning of this year; have the long-term unemployed shown any tendency to find jobs faster? And the answer is no.

Let me parse this a bit more, and ask, how was it, exactly, that reduced benefits were supposed to encourage employment in the first place?

Making the unemployed miserable arguably increases labor supply, as workers become less choosy and more willing to take whatever job they can find. But the US labor market in 2014 isn’t constrained by supply, it’s constrained by demand: given what firms can sell, they have no need for as many hours of work as workers are willing to give.

I argued that the policy change would boost aggregate supply and increase job growth. It turns out that I was correct; payroll employment growth in 2014 surged to 3 million, versus 2.3 million in 2013 and 2.2 million in 2012.

Both aggregate supply and aggregate demand play a big role in the labor market.

BTW, the WSJ article cites one of my colleagues at the Mercatus Center:

Some economists like Michael Farren, a research fellow at the right-leaning Mercatus Center at George Mason University, say the state unemployment-insurance cutbacks and policy changes have motivated jobless Americans to undertake faster searches for new work.

Absent the state changes, he said, “you end up with policies created in the crisis that may help smooth the passage through the crisis, but…actually help stall the recovery.”

READER COMMENTS

Matthew Waters

Nov 16 2019 at 3:40pm

Unemployment insurance could be part of it, though I think composition effects are main driver of decrease. Most of 70s increase in unemployment was boomers and women joining the labor force, with higher unemployment. Those composition effects have shifted.

Male 25-54 employment/population is still 3 percentage points lower than 1999 peak, even though all unemployment rates (including U-6) are at 1999 levels. I would be willing to agree that the decline in emp/pop is purely supply-side if compensation growth wasn’t still anemic. But total compensation growth is still anemic, suggesting some slack still exists.

Scott Sumner

Nov 17 2019 at 12:18am

Compensation growth is not a good indicator of slack.

Robert

Nov 16 2019 at 7:15pm

Maybe it’s primarily a metric issue. The prime age employment to population ratio has only just now reached the pre-recession level.

Mark Brady

Nov 16 2019 at 10:13pm

“We don’t know the precise natural rate of unemployment, but according to most estimates the natural rate has fallen from roughly 5%-6% during the 1980s to below 4% today. In Germany, the natural rate has fallen much more dramatically.”

A statement like that requires qualification. The natural rate of unemployment (NRU) is an artifact calculated as a moving average of observed unemployment rates from a period in the past and an assumed unemployment rate for a period in the future. Nothing more, nothing less. For example, N. Gregory Mankiw estimates the NRU for any particular month “by averaging all the unemployment rates from ten years earlier to ten years later. Future unemployment rates are set at 5.5 percent.” (Macroeconomics. Tenth edition. New York: Worth Publishers, 2019. Figure 9-1 at page 180.)

Scott Sumner

Nov 17 2019 at 12:20am

I think we agree. We don’t know the precise natural rate.

Matthias Görgens

Nov 17 2019 at 10:41am

Scott, your post doesn’t really need to talk about the ‘natural rate’, does it? It seems to work just fine when talking about unemployment rate by itself or perhaps some moving average of unemployment.

Scott Sumner

Nov 17 2019 at 4:22pm

There’s a big difference between changes in the actual unemployment rate and the (much smaller) changes in the natural rate. The actual rate might fall due to a cyclical recovery, even without any change in the natural rate.

Thaomas

Nov 19 2019 at 8:33am

But why talk about a “natural” rate of unemployment at all. Sure, something like that might be implicit in a model estimating the effects of unemployment insurance on employment, but to pull it out raises the specter of using it as an indicator of what the Fed would do to stimulate/slow down the economy. It seems inconsistent with NGDP targeting or even the dual mandate. How except by statistical noise does measured employment get “too high?”

Daniel Kahn

Nov 16 2019 at 11:16pm

How confident are you that the policy of reducing unemployment benefits was one of the primary causes of increased employment growth? What about other possibilities like it happened to coincide with the economy finally reaching take off speed because the equilibrium rate finally rose to a level such that money was not as tight as earlier in the recovery? I guess you could argue that the policy contributed to the increase in the equilibrium rate?

Scott Sumner

Nov 17 2019 at 12:21am

I can’t be sure, but it is interesting that Paul Krugman saw it as a test of the supply side view—before the results came in.

ChrisA

Nov 17 2019 at 9:36am

It seems natural rates have also fallen in other countries, the UK for instance, so it can’t be a result of just a change in US state policy. I do wonder if this is due to the widespread adaption of things like EITC in the US and Working Tax Credits in the UK?

Matthias Görgens

Nov 17 2019 at 10:43am

Germany had some labour market and welfare reforms around 2005. That’s also when the chronically high unemployment start coming down slowly but steadily. Even the Great Recession didn’t make too much of a dent.

Of course, that’s only another hint. Not a proof of causality.

Craig

Nov 18 2019 at 9:41pm

It might be a cliche but the internet has significantly reduced transaction costs associated with job seeking. I remember the mid 1990s looking for a job was to look through the classifieds, physically mail out a resume, or perhaps, if you were lucky fax it and hopefully somebody would call you in for an interview. Compare that with the internet today. Night and day.

Mark Z

Nov 19 2019 at 10:49pm

Henrik Kleven recently published a paper finding that EITC didn’t have that much of an effect, and that effects on the labor market often attributed to EITC are more likely the result of state and federal welfare reform, which occurred around the same time as large EITC expansions in the 1990s. Did the UK undertake similar reforms around the same time?

P Burgos

Nov 17 2019 at 5:41pm

Are there examples of countries having high inflation rates solely from tight labor markets? I cannot think of any off of the top of my head. The last time the US had high inflation was in the 1970’s, and my understanding was that a lot of that inflation came from adverse supply shocks (OPEC), and not merely tight labor markets.

Brian Donohue

Nov 18 2019 at 10:10am

It was an empirical question, my intuition matched yours, you were right and Krugman was wrong. That guy has had a really crummy century as a prognosticator. I hope he gets outside financial advice.

Thaomas

Nov 18 2019 at 2:09pm

Maybe the “natural rate of unemployment” never made any sense to begin with. It is just not a structural parameter of the economy and the observed “value” is dependent on monetary policy, level of the EITC, etc. and maybe unemployment compensation too.

Keenan

Nov 19 2019 at 9:34am

Why is the natural rate of unemployment even talked about wrt monetary policy? they seem nearly unrelated. Employment will be full/not full based on frictions in labor market which seems at best tangent to the money market?

Tom DeMeo

Nov 19 2019 at 2:58pm

Well, if I took a step back and asked myself when would we have the naturally lowest rate of unemployment in the course of human history, I would guess there would be a period of time when technology transitioned from analog to digital, and that transition would produce a net peak period before automation effects started to drive employment down.

Comments are closed.