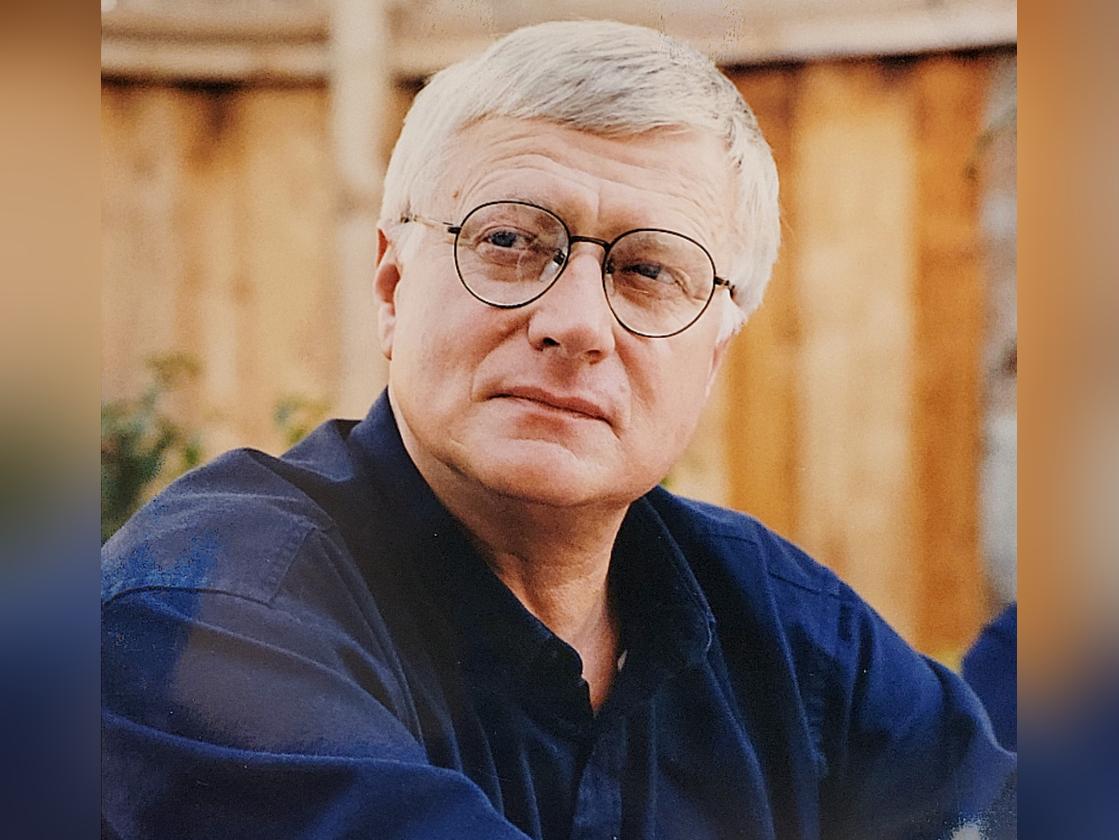

I learned this morning that my former colleague and mentor, Bill Haga, died at age 83 on January 6. Here’s his obituary. Rather than repeat what’s in the obituary, I want to give an appreciation and tell a bit about how important he was in my life.

How He Inspired My Academic Writing

I arrived at the Naval Postgraduate School in August 1984 and quickly found out that most of the faculty had voted against my being hired. But the chairman, Dick Elster, had wanted me and that made the difference. It was at some faculty meeting or faculty lunch in the first few months I was there that I met Bill. I found him fascinating. He had such unusual ideas and when I thought about them, many of them made sense. He quickly struck me as a wise man and someone I wanted to be around.

I wasn’t hired into tenure track but was instead an adjunct who had a year-to-year renewable contract. A tenure slot appeared in the spring of 1986, and I applied. By that time, I had turned around a lot of the faculty’s views on me and I got the offer. I accepted in May 1986.

But that meant that I needed to start trying to publish academic peer-reviewed articles again. I went to see Bill to get his thoughts. I pointed out that with our just having purchased a house, I needed to do a lot of free-lance writing for Fortune and so I was wondering when I would have time for academic articles.

“Do you have any ideas for an article?” Bill asked.

“Yes,” I replied. “When I was the energy economist at the Council of Economic Advisers, I wrote a memo to Marty Feldstein and Bill Niskanen laying out an analysis of the International Energy Agency’s oil-sharing plan that I hadn’t found anywhere in the literature. Marty and Bill thought it was right. So I think I could turn that into a full-fledged article.”

“How long do you think it would take?” asked Bill.

“I think about a month,” I answered.

“That’s the wrong way to think about it,” he said.

“What’s the right way?” I asked.

“Think about it in terms of hours,” he answered. “So how many hours will it take to write each section?”

I was stunned. I thought he was crazy. I had always heard academics talk about how many months they needed. I had never heard anyone talk the way Bill talked. I estimated 10 to 15 hours.

Then he said, “Write a draft and stick it under my door by 8:00 a.m. next Friday.”

I foolishly said I would.

By the next Thursday, I had made a lot of progress, much more than I would have thought possible. But I didn’t think I would make it. Bill seemed inflexible, though, and so I didn’t dare ask for an extension. Instead, I made a little more progress on Thursday afternoon. I went to bed early and set my alarm for 2 a.m. When the alarm rang, I got up, went into my office, and finished a draft by 6 a.m. I stuck it under his door and went home for breakfast and to be there when my daughter, Karen, age one and a half, woke up.

I don’t know if Bill even read my paper. It didn’t matter. I looked at it with fresh eyes the next week, made minor changes, and sent it off. It was accepted and was the beginning of a stream of articles in energy economics that were the core of my research case for tenure 5 years later.

I don’t think that would have happened without Bill.

Bill’s Sense of Humor

Bill had a great sense of humor, especially about the weirdness of academia. If you’ve read Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim, you’ll have a sense of the kind of weirdness and humor I’m talking about.

One particular story stands out. Bill was supposed to put together a course with another professor. I’ll call him Ronald. The course was on communications. They tried to work together but had such big differences that they got in big fights. They quit talking to each other. I’m not sure if Ronald saw the irony. Bill did. “A course in communication, and we’re not willing to communicate,” he said, grinning.

Bill as Teacher

Bill was legendary as a teacher. When we had students in common, they would tell me about some of his methods. He did case courses and would call on people when they least expected it. So, for example, if student A had been called on the previous class and had done a so-so job, student A, early in the course, would think he wouldn’t be called on again for at least a few weeks.

Wrong. Bill would make sure to call on him the next class. This strategy completely worked to cause a huge percent of the students to prepare.

Bill also had a legendary “echo jar,” labeled as such. If a student asked a question that already been answered, he or she had to put a quarter in the echo jar. By the end of the course, with about 25 students in the class, there were a lot of quarters. He would take the quarters and buy as many doughnuts as they would buy and bring them to class. There were always a few left over and he would put them in the chair’s assistant’s office. I always had one or two.

Bill as Baseball Fan and Commentator

If you’ve read Moneyball, you know about the 20-game winning streak the Oakland A’s had in 2000. Well, Bill and I had driven from Monterey to Oakland for that game. The A’s were up 11-0 over the Kansas City Royals but KC clawed its way back to an 11-11 tie.

Here’s how Shayna Rubin sets it up for Scott Hatteberg’s home run in the bottom of the 9th:

All of 55,000 eyes were watching Hatteberg launch that 1-0 pitch off Royals closer Jason Grimsley that Sept. 4 night. Just an hour earlier, when the A’s had a 11-0 lead, Hatteberg had kicked his feet up with a cup of coffee ready to celebrate history until he realized he was watching his team give up the comfy lead in real time.

Here’s Bill King’s excited commentary on the home run.

When we got in the car after A’s games, we would always turn on the radio to hear the after-game commentary. Bill would take every cliche the commentators used, and there were many, and make droll comments about them that had me in stitches. He did that for this game too.

On the 110-mile drive home, we were so jazzed about the game that I didn’t pay attention to my speed. Driving through a 55-mph zone, I saw a red flashing light in my rearview mirror, looked down to see that I was going 77 mph, and pulled over. Bill and I had the same fear of cops. I lowered my window and put my hands at 10 to 2 on the steering wheel. Bill, in the passenger seat, put his hands on the dashboard. The CHP officer noticed that and said to Bill, with a little humor in his voice, “You can put your hands down.”

The last time I saw him was when I was on sabbatical at George Mason University in the spring of 2007. My wife Rena came for the middle 2 weeks of my sabbatical and we had lunch in Annapolis with him and his lovely wife Carline.

I will miss him.

READER COMMENTS

Thomas Strenge

Jan 11 2022 at 8:39pm

Sad to hear of his passing. Glad to have had him as a teacher at NPS.

Comments are closed.