In a previous post, I challenged James Broughel’s recent suggestion that libertarians should re-evaluate their allegiance to the legacy of James Buchanan. There I focused on Broughel’s claims regarding Buchanan’s radical subjectivism. In this piece, I turn to the implications for welfare economics.

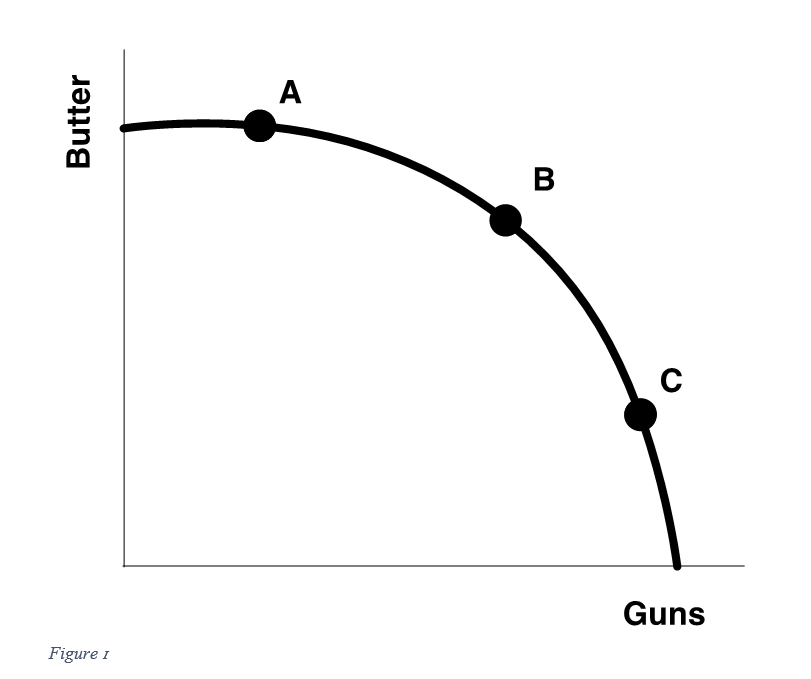

In his piece, Broughel wants to raise the zombie idea of social welfare functions, both in his critique of Buchanan and in an earlier Econlib piece. To see where these arguments go awry, it is helpful to review why mid-20th century economists were trying to construct plausible social welfare functions. Consider Figure 1.

Society faces tradeoffs in the production of various goods, such as guns and butter. (Buchanan would already hate this way of formulating the economic problem.) The concave curve is the set of possible efficient allocations of scarce productive resources. As long as society is somewhere on that curve, one cannot have more guns without giving up more butter or vice versa.[1] Suppose one buys, based on some modeling assumptions, that markets might get us in the neighborhood of the frontier. Some well-crafted policy interventions might be able to get us the rest of the way. That does not tell us where on the frontier we would like to go. The concept of economic efficiency cannot tell us whether it is better to be at point A, B, or C.

Economists sought after plausible social welfare functions to figure out where on the frontier to go. The point of a social welfare function is to rank possible states of the social world, even producing rankings among efficient states. This would allow economic science to say something about matters of distribution as well as efficiency without invoking interpersonal comparisons of utility. If markets could get us to efficiency and democracy to distributive justice, we would have a powerful defense of the liberal order.

Enter Kenneth Arrow. Arrow posits that a social welfare function should exhibit the same sort of rationality that economists typically posit of individual choosers. One feature of such rationality is transitivity: if A is preferred to B, and B to C, then A should be preferred to C. One way to get such rationality at the level of social orderings is to appoint a dictator. As long as the dictator is rational, the ranking of social states will be rational. For Arrow, this is an unattractive answer to the question that social welfare functions were meant to solve.

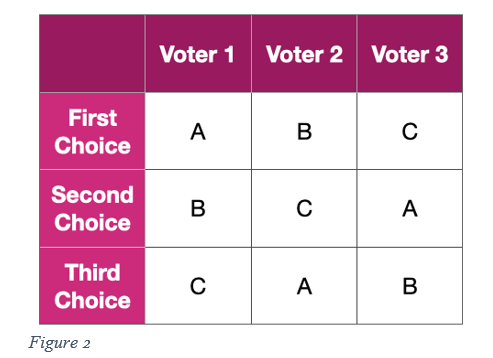

Arrow sought an aggregation procedure that would start from individual preferences and generate a set of rational social preferences. One constraint Arrow places on such a welfare function is the “independence of irrelevant alternatives” (IIA) which is meant to create the transitivity condition noted above. Majority rule cannot ensure this condition, because of what has long been called the Condorcet Paradox or Condorcet Cycle. If voters with the preference orderings in figure 2 confront pairwise choices, A defeats B and B defeats C, but C defeats A. There is no determinate will of the majority. If this is true for the trivial case of three voters and three options, it becomes even more likely as we increase the number of voters and the issues they might care about.

What is now called Arrow’s impossibility theorem shows that there is no collective decision procedure that satisfies the IIA alongside the other assumptions.

Back to Broughel. He argues that IIA is a bad assumption:

Broughel has attempted to engineer a situation in which a third “option” is in fact relevant. But getting into college is not a third option. It is a further consequence of the second option that would naturally inform the decision as to whether to party or not. There is of course no possibility of a paradox with only two options and one rational decision maker.

The next paragraph is even more problematic:

Arrow’s theorem does not entail that only immediate consequences should count in preference orderings. In fact, Arrow says the exact opposite. One of the other assumptions he makes is “universal domain:” all logically possible individual preference orderings are allowed.[2] This would include preferences for benefits that only manifest in the long term.

And Arrow’s theorem is in no way the foundation of modern cost-benefit analysis. Cost-benefit analysis concerns efficiency. Specifically, empirical cost-benefit analysis relies on the concept of Kaldor-Hicks efficiency since monetary outlays are measurable. Social welfare functions are mathematical constructs meant to rank Pareto efficient outcomes. Arrow spends an entire chapter of Social Choice and Individual Values arguing against the Kaldor-Hicks approach as a satisfactory social welfare function, so it is supremely odd to claim that his work is the basis of cost-benefit analysis.

Broughel’s next argumentative move is no better. He makes similar claims in his articles on Arrow and Buchanan.

Ironically, rejecting the use of any social welfare function at all, as some libertarians do, also implies rejecting the market process—which itself is guided by a social welfare function of sorts. Arrow himself acknowledges as much in his book that presents the impossibility theorem, Social Choice and Individual Values, when he concludes that “the market mechanism does not create a rational social choice.” Strangely, most libertarians have failed to heed the lesson.

Buchanan’s dismissal of the reasonableness of the social welfare function concept altogether likely contributed to many libertarians accepting Arrow’s theorem in a knee-jerk fashion. Yet, the market process itself operates under the guidance of a particular social welfare function (as Arrow understood, despite Buchanan arguing the opposite). Thus, libertarians who accept Buchanan and Arrow’s ideas inadvertently reject the process underlying the market, which forms the foundation of modern civilization.

Note the utterly strange claim that the market process is guided by a social welfare function. This is somewhat like saying that individual markets are guided by supply and demand diagrams. Not so. Supply and demand diagrams are a model of how markets work. But Broughel’s claim is even stranger than this because a social welfare function is a normative rather than positive construct. Its purpose is not predictive but evaluative. This comes across like a bizarre version of Hegelianism[3]: the social welfare function is realizing itself through the market process. That there is some funky metaphysics.

Perhaps Broughel means something different, though. Perhaps he means that markets must be judged by whether they produce rational social choices in accord with a social welfare function. This is the only way I can make sense of the claim that Arrow understood the importance of social welfare functions to the defense of markets. To which I respond: why?

Let me propose an alternative: social welfare functions were never that important to begin with. There is no reason to believe that the emergent properties of an economic or political system will conform to some set of rationalistic criteria derived from a model of individual decision making. Neither democracy nor markets aggregate preferences into a coherent ordering of social states. So what? This is, of course, Buchanan’s original point that Broughel links to. Arrow was simply wrong to claim that a system is justified to the extent that it approximates rationality.

For Broughel’s claim to be true, it must be the case that only a social welfare function is capable of underwriting normative support for markets (or democracy). But there are many alternative normative standards that could provide such support. Efficiency. Innovation. Discovery. Coordination. Natural rights. Basic rights. Public reason. Economic growth. Social morality. Virtue. Or mere agreement. One might be forgiven for believing that virtually any other normative standard is more useful than social welfare functions for judging economic and political institutions.

Description in Deficit

Broughel’s final beef with Buchanan concerns Buchanan’s view on deficits as burdening future generations.

Here Broughel echoes an argument initially made by Abba Lerner. Scarce resources cannot be literally borrowed from the future. The “social cost” of deficit financing is always paid today. Wealth is transferred from taxpayers to bond holders, but the scarce resources expended are the same whether public expenditure is financed through taxation or debt.[4]

Buchanan’s rejoinder is that future taxpayers do suffer a utility loss from having to transfer resources to bondholders. Regardless of the wisdom of the government spending, future taxpayers would be even better off if that spending had been financed with present taxation. In essence, Lerner is focused on the objective side of the ledger and Buchanan with the subjective side. Both insights are straightforward and difficult if not impossible to dispute.

Karen Vaughn and Richard Wagner reconcile Lange and Buchanan’s views on debt, along with Robert Barro’s concept of Ricardian Equivalence. The key insight of Barro’s view is likewise straightforward and uncontroversial: deficits are future taxes. Deficits thus reduce the present discounted value of assets held by individuals in the present.

Reconciling these three views requires recognizes that individuals are heterogeneous. Some have children, some do not. Some like their children more than others. There will thus be variation in intergenerational altruism. For those with lower levels of intergenerational altruism, deficit spending is a lower cost method for financing government expenditures. Deficit financing thus represents a transfer of wealth from those with high to those with low intergenerational altruism. It is a method of changing who pays for any given government expenditure. If some individuals who have political influence on the margin have less than complete intergenerational altruism, deficit financing also results in increasing the net amount of government spending.

Wagner has further developed this point in later work. Many decisions about fertility, marginal tax rates, and methods of servicing debt necessarily lie in the future. Deficit financing thus serves as a means of obscuring who ultimately bears the burden of government spending.

Broughel’s critique of Buchanan here is not based on an error but rather simply an incomplete picture. The only statement of his concerning deficits that I take substantive issue with is this:

Though he does not take it as far as others, this Lerneresque view is very close to that used by proponents of Modern Monetary Theory. Scarce resources used in government consumption or investment must come from somewhere. The ability to roll over debt does not make government spending into a magic goodies creator. We must keep in mind all three aspects of deficits—scarce resources, future utility losses, and Ricardian equivalence—in order to grasp the full consequences of deficit financing.

Concluding Thoughts

No thinker is above critique. There are many arguments in Buchanan that, in my view, simply do not work. But Broughel has failed to identify any substantive flaws in his thinking. Radical subjectivism does not obscure the losses imposed by government policies. Buchanan’s thoughts on debt do not imply that scarce resources can be shifted into the future. And social welfare functions should be left in the ground where Arrow and Buchanan buried them.

One final point of clarification: Buchanan’s work should not be judged by how useful it is for libertarianism. It should be judged on its own merits, whatever conclusions they point to. Paraphrasing Peter Boettke, libertarianism is a conversation for children. Liberal political economy is an adult conversation that freely engages with normative considerations, especially about the value of liberty. But it does not prejudge arguments as to whether they conclude that “state bad, market good.” Buchanan’s work is and will remain a vital and central contribution to that conversation.

[1] Alternatively, one could interpret this as a Pareto frontier, in which case it measures preference satisfaction for guns and butter. The same point applies.

[2] For those who hold out hope for social welfare functions, universal domain is actually the best point of attack.

[3] It goes without saying that all versions of Hegelianism are bizarre.

[4] There is a slight qualification in Lerner’s analysis: debt owed to parties external to the country can meaningfully be said to impose a burden. I set this aside to address more important considerations.

Adam Martin is Political Economy Research Fellow at the Free Market Institute and an assistant professor of agricultural and applied economics in the College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources at Texas Tech University.

For more articles by Adam Martin, see the Archive.

READER COMMENTS

Thomas L Hutcheson

Sep 28 2023 at 11:32pm

“Deficit financing thus represents a transfer of wealth from those with high to those with low intergenerational altruism.”

Which will affect the welfare of future generations, so in THAT sense deficits probably impose a burden on future generations.

A more down to earth way of looking at it is both a tax and borrowing remove resources that the taxpayer or bond buyer could have used for an activity with a certain NPV. Which the aggregate has the higher NPV? (My guess is the bond buyer) by choosing to remove resources from the higher NPV activity we reduce future income, hence impose a burden. Collection of future taxes and payment of future principle ad interest are uses of that future income and do not affect its size, which is what is relevant for the tax/borrow decision today.

nobody.really

Sep 29 2023 at 12:18pm

Having spent a career striving to promote the welfare of zombies–a highly stigmatized population–I found the title of this post most misleading.

Jon Leonard

Sep 29 2023 at 10:49pm

Is there some relevant extension to Arrow’s Theorem? In the usual form it only deals with ordinal preferences. If, in hypothetical contrast, we ask each ‘voter’ for their utilities for various policies, there’s no numerical problem in just adding them together. There are, of course, practical problems in polling involving rational ignorance and tactical voting, so that’s not viable. But it seems like Arrow’s Theorem is almost irrelevant to the argument at hand.

Thomas Hutcheson

Sep 30 2023 at 8:44am

Yes. After proving that the bumblebee cannot fly, what next?

Jon Murphy

Sep 30 2023 at 10:02am

Ranked choice voting and other methods attempt to do what you suggest, but even then they can result in the Arrow problems.

Of course, there’s also the larger problem that utilities don’t exist in any meaningful, additive sense, so the whole question is moot, but that’s a matter for another time.

Don Boudreaux

Oct 1 2023 at 12:04pm

Nicely done indeed.

It’s worth explicitly noting that, contrary to what is perhaps the impression left by reading James Broughel’s original post, Buchanan himself explicitly recognized that resources used today in government projects funded with debt are, of course, used today in those projects.

That such resource use occurs in the current period – and that, therefore, whatever else those resources would otherwise have been used to produce in the current period remain unproduced in the current period – is the most obvious seeming rebuttal to Buchanan’s point. And so it was a rebuttal often used – meaning, a rebuttal that Buchanan was well aware of and, hence, dealt with (as Adam explains well above).

nobody.really

Oct 5 2023 at 11:25am

We just had a timely illustration of this in the House of Representatives:

Faction A: 208 people who thought that Kevin McCarthy is was too conservative/doctrinaire to serve as Speaker of the House.

Faction B: 210 people who wanted to retain McCarthy as Speaker.

Faction C: 8 people who thought Kevin McCarthy was insufficiently conservative/doctrinaire to serve as Speaker.

Arguably McCarthy reflected a reasonably centrist choice, or perhaps a slightly-more-conservative-then-centrist choice. But Factions A and C–factions that share little other than a dissatisfaction with McCarthy–joined to expel him. If, instead of asking “Are you dissatisfied with McCarthy?” the question had been “Who would you rather have serve as Speaker of the House?,” I expect we would have seen a different result.

Even though Factions B and C voted against each other in expelling the Speaker, I expect they’ll vote together in installing the next Speaker. Will Faction A (Democrats), who voted to expel McCarthy, be happier with his replacement? That’s far from clear. “Be careful what you wish for….”

Comments are closed.