Thanks to EconLog readers, I’ve finally located some real empirics on what I call “firing aversion” (see here, here, and here). My favorite piece so far: “Cultural Influences on Employee Termination Decisions” (European Management Journal, 2001). The authors analyze a survey of about 300 managers from financial institutions in England, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. Key idea: The survey describes four hypothetical workers, and tells each manager he has to fire one. Who do they pick – and why?

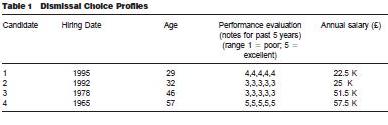

Here are the worker profiles each manager sees:

1. Young, good performance, cheap

2. Young, average performance, cheap [but not as cheap as #1 – B.C.]

3. Middle-aged, average performance, expensive

4. Older, excellent performance, expensive

Who gets fired? Almost half the respondents make what sounds like the profit-maximizing decision – firing #3. But #2 is almost as popular, and almost 15% fire the older but excellent performer. (See the bottom row of Table 2 for details). More strikingly, though, answers vary radically by country:

What are these managers thinking? The authors explain that “Only two justifications are consistently cited within the top five reasons for each country.”

The first takes advantage of the existence of early retirement programs that are commonly implemented in many countries and industrial sectors. This is clearly an easy choice fitting very well with the organizational justice reasoning provided above. The older employee is ‘given a gift’ as some French respondents put it. He no longer must trudge into the office and work but happily retains a large part of his salary. No hard decision must be made which would attack the sense of self-worth of someone who was being fired because he was no longer sufficiently productive. Only a few, largely Anglo-Saxon respondents, were concerned about the organizational impact of ‘throwing someone out at their peak’.

In short, many managers prefer to fire the person who will suffer the least – or actually benefit. Of course, this isn’t the only motive. Plenty cite profitability (and/or desert) as well:

The second ranked reason however is a much tougher justification. Someone should be fired if his performance longer merits his salary. This was respectively the first and second criteria used by the English, German, and Spanish respondents. This justification appears to reflect the consequences of classical economic theory more than the social justice model. If you are under-performing (relatively) you must go (when times are tough). Your commitment and years of service are not sufficiently important to your colleagues or company.

Other common rationales for firing include: “good chance to find a new job because of youth,” “good chance to find a new job because of skills,” and just “age.” On the latter, check out this neat graph of “Average Age of Dismissed Employee By Country.”

What does all this have to do with firing aversion? Plenty. The premise of the hypothetical is that the manager’s firm is losing money so it must let someone go:

The company lost 5 million pounds last year and will probably lose more next year. The firm’s economic problems started several years before the recent recession but it was always able to avoid staff reductions. However now this is no longer possible and some employees must be sacrificed.

The scenario gives the managers a great excuse to fire on the basis of profitability alone. But most don’t. Instead, they act like normal human beings. They consider the effect on the welfare of the worker as well as the profitability of the company. Why bother? Because firing someone makes them feel bad – and the more the discharged suffers as a result, the worse they feel. Imagine how few people they’d fire in an easier scenario where the company was fairly profitable but could be even more profitable if it trimmed some fat.

Many economists will dismiss this paper on methodological grounds: “You can’t learn anything by asking people about their behavior in hypothetical scenarios.” I say these economists are being insufferably dogmatic. Yes, people exhibit social desirability bias; they overstate their virtue when they don’t have to put their money where their mouth is. But that’s a lame reason to ignore their words entirely.

Indeed, it’s possible that the survey overstates managers’ focus on profitability. A manager is supposed to act in his company’s best interest. It is his fiduciary responsibility. So social desirability bias could easily lead managers to exaggerate their willingness to put personal feelings aside for the good of the company. (“Sure, I work for the stockholders. But what is to become of poor, poor Jimmy Jones?”)

Bottom line: Put yourself in the shoes of someone who has to fire someone. Can you honestly say that profitability is the only factor you’d consider? Even if your answer is yes, think about how typical you are. Can you honestly say that virtually everyone who makes firing decisions is as unconflicted as you are?

READER COMMENTS

Eleazar Melendez

Jun 3 2012 at 11:26pm

Haven’t read the full referenced paper but, assuming you’ve summarized it correctly (which I have no doubt you likely have) linking the findings to firing aversion seems like a rather large logical leap.

The paper seems to be finding that (1) managers take considerations outside just profitability when firing and that (2) they don’t like firing people. Going from there to saying they will not do lay offs when times are good to get rid of ‘fat,’ however, supposes managers will not do things that makes them personally uncomfortable for the sake of their job, career, bonus, etc. (and that’s just silly) or that firing someone is so unsavory to the average manager they’ll avoid doing it as long as they can (i.e. as long as the business is in the black). The papers don’t come down on that second issue, which is the crux of the firing aversion debate.

Bryan Willman

Jun 3 2012 at 11:51pm

I wonder how much the “shadow of the law” or the “shadow of a contract or union” hangs over the thinking of those surveyed?

That is, their choices are colored by law or contract even if that particular law or contract doesn’t apply to this case. People can be “trained” by litigation and union disputes to make certain choices, and not realize it.

There can also be an issue of expected futures. Is the 57 year old sure to retire in 2 or 3 years regardless? Is the 32 year old sure to jump ship?

Saturos

Jun 4 2012 at 6:47am

I still don’t think “aversion” is the main explanation for rigid nominal contracts – at least not on the employer side.

Thomas Boyle

Jun 4 2012 at 8:16am

I think the shareholders have a significant interest in their company being seen as “a good place to work,” which will certainly be affected by perceptions of caring/callous treatment of employees. “Ruthless” employers will still attract those (over)confident enough to believe they are top employees, but the whole workforce will be more expensive because the self-perceived elite expect higher pay, and the self-perceived non-elite would rather work somewhere less ruthless (unless you pay them enough).

Managers who care have benefits, as well as costs.

Andrew

Jun 4 2012 at 10:10am

As someone that has “fired” people many times, I can say that some people are easier to “fire” than others. It’s really hard to let a quality employee go for borderline reasons but it’s really easy to let a bad employee go for good reasons.

soonerliberty

Jun 4 2012 at 10:18am

In Germany, the longer one is with a company, the more the company has to pay to get rid of them. They have to give them longer notice and continue paying for a few years. The social state gives a disincentive for firing. Did this study take such legal considerations into account?

Noah Yetter

Jun 4 2012 at 11:14am

I was a manager for the last year and a half. Firing aversion is very, very real.

Glen Smith

Jun 4 2012 at 11:46am

In my experience, managers, like everyone else, always make the decision that they perceive optimizes their personal utility. If this happens to coincide with what’s best for the company, great.

Floccina

Jun 4 2012 at 1:07pm

Firing someone is difficult. I once had to fire a guy and he cried and my boss overrode my firing. Of course in the case described above it is easier because it is just a layoff, that is the company will not hire a replacement.

ajb

Jun 4 2012 at 10:43pm

I like the cultural angle, but it seems obvious from the study that they haven’t ruled out structural and legal considerations. Indeed, the opportunity costs produced by differing laws about retirement, limits on firing, union regs, etc. would seem to explain part of the so-called “cultural” differences. For a genuinely “cultural” explanation, one would have to net out the effects of the differing opportunity costs for both employers and employees.

Ryan S.

Jun 5 2012 at 12:35pm

My first response was a strong methodological concern that is along the lines, but distinct from, the one you mention.

How many of the respondents have actually faced this choice and then had to live with the results? I can imagine the responses from “experienced firers” being dramatically different than those that have not faced the situation.

If you fire #4, you then have to live with the pain of trying to replace his/her productivity. If you fire #2, you then have to live with being $26.5k higher on your salary budget.

The magnitude of these “after the fact” problems is perhaps not fully appreciated by inexperienced responders.

I read a portion of the referenced paper, and the following line eliminated my hope that the authors had controlled for this issue “It (the survey) concentrated on isolating managers and organizations that have traditionally been the most protected from international competition”

Now, which of the surveyed countries has had the strongest economy over the last few years, and thus the least experience at firing employees in “hard times”?

David

Jun 5 2012 at 4:07pm

All of you missed the American solution: Hire a consultant. The consultant will tell you to fire everyone and then help you find a firm you can outsource to. Collect your bonus for saving money. Quit before the consultant’s $200k invoice arrives.

blink

Jun 5 2012 at 10:38pm

Germany sounds like academe, applying something like a de facto tenure rule. Also, taking the culture as given, manger decisions are constrained; the “profit” choice may violate social norms and send a bad signal (willing to cut corners, shirk, etc.) about the manager to employees and others.

DK

Jun 5 2012 at 10:57pm

This alone shows why Germany is doing so well in among Europeans. Firing #2 is the only sound decision.

Maia

Jun 8 2012 at 4:15pm

I recently had an unpaid voluntary post as a cleaner in rural poor south Germany. People there didn’t know i was unpaid, at the time i was 36. Everyone reacted with shock when i told them i’d started there, and gushed with congratulations at my extreme good fortune to procure a (horrible, lowpaid, part-time, backbreaking) job “at my extremely old age”. It was too many people to be random or fake; i got the impression that anyone over 30 probably won’t find work easily in Germany. (Bearing in mind that this job required you to be able to 1) show up on time 2) use a hoover, so wasn’t beyond any of the adult population.)

Andrew Norman

Jun 11 2012 at 11:00am

Having a job isn’t good enough. Each person/household needs multiple revenue streams – a job is a job – very few have careers anymore.

Comments are closed.