Paul Krugman has a new post that summarizes Keynesian economics:

I would summarize the Keynesian view in terms of four points:

1. Economies sometimes produce much less than they could, and employ many fewer workers than they should, because there just isn’t enough spending. Such episodes can happen for a variety of reasons; the question is how to respond.

2. There are normally forces that tend to push the economy back toward full employment. But they work slowly; a hands-off policy toward depressed economies means accepting a long, unnecessary period of pain.

3. It is often possible to drastically shorten this period of pain and greatly reduce the human and financial losses by “printing money”, using the central bank’s power of currency creation to push interest rates down.

4. Sometimes, however, monetary policy loses its effectiveness, especially when rates are close to zero. In that case temporary deficit spending can provide a useful boost. And conversely, fiscal austerity in a depressed economy imposes large economic losses.

If I were to do the equivalent for market monetarism, it might look something like the following:

1. Economies sometimes produce much less than they could, and employ many fewer workers than they should, because there just isn’t enough spending. Such episodes occur because monetary policy is too contractionary, causing NGDP to fall relative to the (sticky) wage level.

[As an aside, economies can also produce too little due to real shocks, such as higher minimum wages. That’s also true in the Keynesian model.]

2. There are normally forces that tend to push the economy back toward full employment. But they work slowly; a hands-off policy toward depressed economies means accepting a long, unnecessary period of pain.

[Notice this one is identical.]

3. It is often possible to drastically shorten this period of pain and greatly reduce the human and financial losses by “printing money”, using the central bank’s power of currency creation to boost M*V, i.e. NGDP, via the “hot potato effect”.

4. Monetary policy remains highly effective at the zero bound. As a result, demand-side fiscal policy is mostly ineffective in countries with an independent monetary authority—offset by monetary policy. Fiscal actions that shift the aggregate supply curve, however, can be effective.

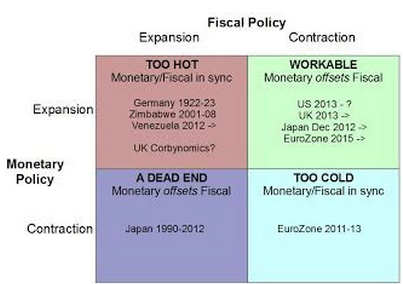

James Alexander has a new post with a really useful graph:

HT: Dilip

READER COMMENTS

Tom Brown

Sep 18 2015 at 2:09pm

I was wondering what you were going to think of Alexander’s quad chart. I guess this means you approve.

ThomasH

Sep 18 2015 at 3:20pm

The following from Krugman’s British twin, 🙂 Simon Wren-Lewis, is interesting

ThomasH

Sep 18 2015 at 3:39pm

I think 1 is correct, but “tight policy” has to be identifiable independent of decreases in NGDP to avoid the whiff of tautology.

I think 3 could be expanded by recognizing that the expansion of M normally lowers long term interest rates which causes rational governments to increase levels of activity with future benefits and present costs as more activities pass the discounted NPV test.

I think 4 needs to be amended to recognize that however effective monetary policy can be at the ZLB, it is effective only if it is used. If constrained by, for example, an inflation rate ceiling or fears for the size of the monetary authority’s balance sheet, it may be unable to provide the stimulus needed to restore NGDP (or even the price level) to its pre-crisis trend. And if monetary policy is so constrained, it will not necessarily offset the expansionary effects of fiscal deficits undertaken in response to lower borrowing rates.

Brian Donohue

Sep 18 2015 at 3:49pm

Great stuff, Scott!

MikeP

Sep 18 2015 at 3:59pm

I think 3 could be expanded by recognizing that the expansion of M normally lowers long term interest rates which causes rational governments to increase levels of activity with future benefits and present costs as more activities pass the discounted NPV test.

Be careful about the trap here. The decision by the rational government must still hinge on whether the investments are positive investments, not just whether interest rates are low.

Interest rates are low for the private sector too, so they will find those same activities worthwhile. If the government outbids the private sector on the supply side, this is a definite negative for the economy.

Scott Sumner

Sep 18 2015 at 7:29pm

Thomas, SWL obviously doesn’t know much about MMT. The MMTers consider their model to be very different from Keynesian economics, and they’re right.

You said:

“I think 1 is correct, but “tight policy” has to be identifiable independent of decreases in NGDP to avoid the whiff of tautology.”

Can you explain how point 1 is a tautology, if monetary policy is defined in terms of NGDP growth?

You said:

“I think 3 could be expanded by recognizing that the expansion of M normally lowers long term interest rates”

I don’t agree that this is the “normal” response of long term interest rates to an increase in M.

You said:

“If constrained by, for example, an inflation rate ceiling or fears for the size of the monetary authority’s balance sheet, it may be unable to provide the stimulus needed to restore NGDP (or even the price level) to its pre-crisis trend. And if monetary policy is so constrained, it will not necessarily offset the expansionary effects of fiscal deficits undertaken in response to lower borrowing rates.”

I don’t agree with this. If monetary policy is constrained by an inflation rate ceiling at the zero bound, then it will still be likely to offset the effect of fiscal stimulus—or at least that type of fiscal stimulus that is inflationary.

ThomasH

Sep 18 2015 at 7:29pm

@ Mike P

No disagreement. I don’t think it is a stretch to think that governments and private firms and individuals have different opportunity sets and the idea of NPV takes into account the opportunity costs in, for example private sector activities, of the inputs into the activities being subjected to the NPV test.

The “Keynesian” insight for fiscal policy is not much more than that governments do NOT have to behave like credit constrained consumers and that the decision function for which and how much activity to undertake does NOT change according to the size of the the debt or any of its derivatives with respect to time. That the marginal costs of some inputs into the marginal activities funded during recessions is less than their market prices gives rise to the “multiplier.”

Note that this analysis works only if monetary policy is constrained. If monetary policy is unconstrained, then the additional borrowing will mean less borrowing in the private sector and so a full offset. [Of course the government activities might still be worth carrying out, but only if the returns were higher than the private activities displaced, as would be the case at full employment.]

“Constrained” monetary policy seems to be the norm not the exception since 2008 because the Fed seems unable to take the actions necessary to keep the price level growing at 2% per year because it is constrained by a 2% pa inflation ceiling but (apparently) only by a 0% per year inflation floor, leaving the actual price level to wander between widening bands.

Kevin Erdmann

Sep 18 2015 at 7:49pm

Shouldn’t temporary fiscal stimulus have many of the same problems that temporary monetary stimulus does?

Steve Y.

Sep 18 2015 at 9:01pm

One of the most successful economic interventions of my lifetime occurred during the Reagan-Volcker regime of the early 1980’s, when high “permanent” inflation was defeated, setting off a long boom in the economy and stock market.

Wasn’t their solution in the Dead End (fiscal deficits/tight money) quadrant?

Doesn’t this example show that robots will never replace economists?

sourcreamus

Sep 18 2015 at 9:35pm

It seems to me that before the great recession Keynesians would have said that fiscal policy was the first response and monetary policy was only if fiscal did not work. However, since the stimulus package did not work and QE did they are retroactively trying to claim they wanted QE all along.

Is that a fair statement?

James

Sep 18 2015 at 10:34pm

The concept of financial losses from recessions makes no sense from a macroeconomic perspective. Financial markets are zero sum games. If stock prices go down due to a recession, that is a loss to those who bought before the decline but a gain to the other side of the trade. All of this just rearranges purchasing power between people. Total consumption is still bounded by production.

Spending more in response to the printing of more money makes society better off only if there are gains from trade associated with these incremental expenditures. If the printing of money leads people to overestimate the trajectory of their real incomes and wealth, the incremental expenditures will have two opposing effects: The consumer surplus from these transactions will be negative but the producer surplus will be positive. Since GDP includes producer surplus (profit in the incomes formula) but excludes consumer surplus, things will look better on paper even though they may well be getting worse in terms of people actually satisfying their preferences.

If the recession was initially caused by people spending less because they realize they overestimated the trajectory of their incomes and spent to much during the last period of accelerated money printing, then the printing of more money will only make the problem worse.

If monetary policy affects the economy at all it can only do so by creating market inefficiencies. Say, for example, everyone wants to hold 50% stocks, 40% bonds and 10% cash and the central bank decides to print money to buy bonds. If financial markets are efficient then everyone is already at their target allocations and the central bank will find no counterparty willing to take cash for bonds at the going asset market prices. In order to get someone to deal with them, the central bank will have to either get people to believe that their target allocations should change whenever the Fed changes policy or pay counterparties a premium to deviate from their target allocations, either of which would lead to mispricing of financial assets.

James Alexander

Sep 19 2015 at 4:07am

Steve Y

Good question about the Volker era. It was messy, especially at the start.

NGDP was strong and then merely healthy from 1982 onwards. Best source for this era is, as ever, Marcus Nunes and his charts.

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2012/09/11/the-volcker-moment/

If you read my post I did mention a “perfect” state of neutral monetary policy, with a stable but healthy level of NGDP expectations. This was the Great Moderation and thus doesn’t appear on the quad.

Fiscal policy was relatively easy. That it didn’t hurt RGDP, and probably helped, was due to it being supply-side fiscal policy.

ThomasH

Sep 19 2015 at 7:25am

@James

Your analysis does not deal with the cases in which production is less than potential because of a negative demand shock and there is unemployment.

@sourcreamus

Before the great recession I think most Keynesians would have said that “conventional” monetary policy was ineffective. I’m not aware of a discussion of QE and criticisms of QE did not come from Keynesians. If monetary authorities are constrained in the amounts of assets they can buy (whether because they will buy only ST government securities or limited amount of longer term securities) a higher public deficit will enable greater monetary stimulus. As I this was the case in 2009, why do you think the limited “stimulus” did not work? That’s what the Fed was asking for.

EclectEcon

Sep 19 2015 at 8:10am

This post is one of the best overview summaries of macro policy that I have ever read. Thank you!

Michael Byrnes

Sep 19 2015 at 8:38am

Scott, what do you make of this comment from John Cochrane:

If you just look out the window, our economy looks a lot more like one in which the Fed is keeping rates high, by sucking deposits out of the economy and paying banks more than they can get elsewhere; not pushing rates down, by lending a lot to banks at rates lower than they can get elsewhere.

Shayne Cook

Sep 19 2015 at 9:33am

I do love little boxes, especially when they have other little equally-sized, uniformly distributed boxes embedded in them. Such devices are sometimes useful for establishing a conceptual framework for common understanding and discussion.

However, the problem with little boxes in the context of economic discussions is that they depict a closed economy. Even more specifically, within the context of just the U.S. economy, its commonly-referred-to macro metrics (M, V, GDP, NGDP, RGDP, etc.) – and the supposed relationships between them – assume a closed economy for validity. The same criticism applies to Keynes’ models and assumptions, by the way.

As logically compelling as these models are, for whomever is proposing them and their adherents, the question is the same: “What happens to your assumptions and relationships when the economy isn’t closed and constrained as your “little box” depicts?”

It might be past time to think “outside the box.”

@sourcreamus:

You observed that “… the stimulus package did not work.” You’re correct. I would say though that it didn’t work as a “Keynesian” remedy, because it wasn’t “Keynesian”. It was more in the nature of a “Krugmanian” remedy. And his remedies will never work, not the least of reasons because they aren’t “Keynesian”, nor were they.

Arnold Kling already addressed this Krugman article, and my comments there will provide a bit more thorough explanation of why the “stimulus package” wasn’t Keynesian.

The question remains as to whether the “stimulus package” would have “worked” had it actually been truly Keynesian. I’m not a “Keynesian” myself – most notably because Keynes’ (true) models/relationships/remedies are also based on the closed economy assumption.

Relevant, but as an aside, Pedro Schwartz has a marvelous article on the real Keynes and real Keynesian thought here on EconLib. (Can’t say I was enchanted by the title, but the article is very good.) It is very telling, in terms of the decided difference between actual Keynesianism, and the rather ineffectual Krugmanism (“stimulus package”).

James

Sep 19 2015 at 3:30pm

ThomasH:

Everything I wrote is true regardless of whether or not there is a negative demand shock. Added spending only improves the situation if there are gains from trade. There is no circumstance in which added spending can improve the world unless there are positive gains from trade associated with those transactions. Same for the rest.

J Mann

Sep 21 2015 at 9:48am

Wait – isn’t Krugman’s #4 one of the exact things his defenders have been assuring us he never said?

Jose Romeu Robazzi

Sep 21 2015 at 3:16pm

This post is very revealing. I have a lot of problems with #2, which is apparently a consensus view.

“2. There are normally forces that tend to push the economy back toward full employment. But they work slowly; a hands-off policy toward depressed economies means accepting a long, unnecessary period of pain.”

Who gets to decide what is “slowly”, and what is “unnecessary period of pain” ? What is the objective of a market eonomy? Is it “utilize all resources avalilable” or “meet consumers demands” ?

Having said that, I agree that too tight money can be counterproductive, but I don’t think that resource underutilization is a good reason to macro manage a market economy.

Andrew_M_Garland

Sep 23 2015 at 1:56am

Mr. Sumner,

I read your article – The “Hot potato effect” Explained

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=23314

It explains that the value of a fixed amount of gold or money goes down if much more gold is found or if much more money becomes available. It is an explanation of how inflation happens: resource prices in gold or money increase until people in aggregate are willing to hold the new volume of gold or money.

I am puzzled about what the conclusion is? What is this effect supposed to do, other than reduce the wealth of people already holding gold or money? Could you point to it in that post?

At that post, you explain that prices adjust almost immediately upon announcement, even if the new gold or money will appear in two years. People in aggregate can’t “get rid of”, can’t receive the prior value for their holdings, when everyone hears the announcement. They suffer the loss.

Prior, say M*V = 1000 * 1. After, M*V = 2000 * 1, but remains 1000 * 1 adjusted for inflation. What is the point?

Ben Kennedy

Sep 23 2015 at 12:24pm

“1. Economies sometimes produce much less than they could, and employ many fewer workers than they should, because there just isn’t enough spending.”

I was looking at some document with employment numbers by sector over the recession (I think it was from England). It struck me that in the construction sector, employment was dramatically down (over 20%), but in other sectors it was flat or even rising. Maybe we should not reason from an employment change to talk about what should happen, and start one step earlier. Applying my very rudimentary understand of Arnold Kling’s PSST, the drop in construction employment was the result of entrepreneurial discovery that a certain level of construction was not sustainable. The solution is therefore entrepreneurial reconfiguration, and it’s not obvious to me how general monetary policy accomplishes this, when unemployment occurs in specific sectors for specific reasons

Comments are closed.