Suppose you could either save one 10-year-old, or X 80-year-olds. What value of X is morally indifferent?

That is, if you wanted to make the world as morally valuable as possible, when should you switch from saving one youth to X elders?

I suspect that people’s modal answer will be 1. Not the median, and certainly not the mean. But probably the mode.

Why would X=1 be such a popular answer? Charitably, people set X=1 because they sincerely believe that all lives have equal value.

In all honesty, though, I’ve yet to meet a person who merits this charity. No one responds to the deaths of 10-year-olds and 80-year-olds with remotely equal concern. Setting X=1 is one of the clearest-cut examples of Social Desirability Bias I’ve encountered. The lives of the young are plainly much more valuable than the lives of the old, for three reasons.

1. When the young die, they lose far more years of life.

2. When the young die, they are far more likely to lose healthy years of life.

3. When the young die, the people who survive them miss them much more – and miss them for a much longer time.

All things considered, I’d say that a reasonable value of X is at least 100. Probably more like 1,000.

I suspect that many readers will strongly object to this, but on what basis?

Point 1 is clearly a big deal. A 10-year-old can be expected to live another 69 years, an 80-year-old just 9 more years.

Point 2 is also clearly important. Self-reported health dramatically declines with age. And people clearly grade their health on an age-based curve. An 80-year-olds’ version of “good health” is probably what an 18-year-old calls “poor health.”

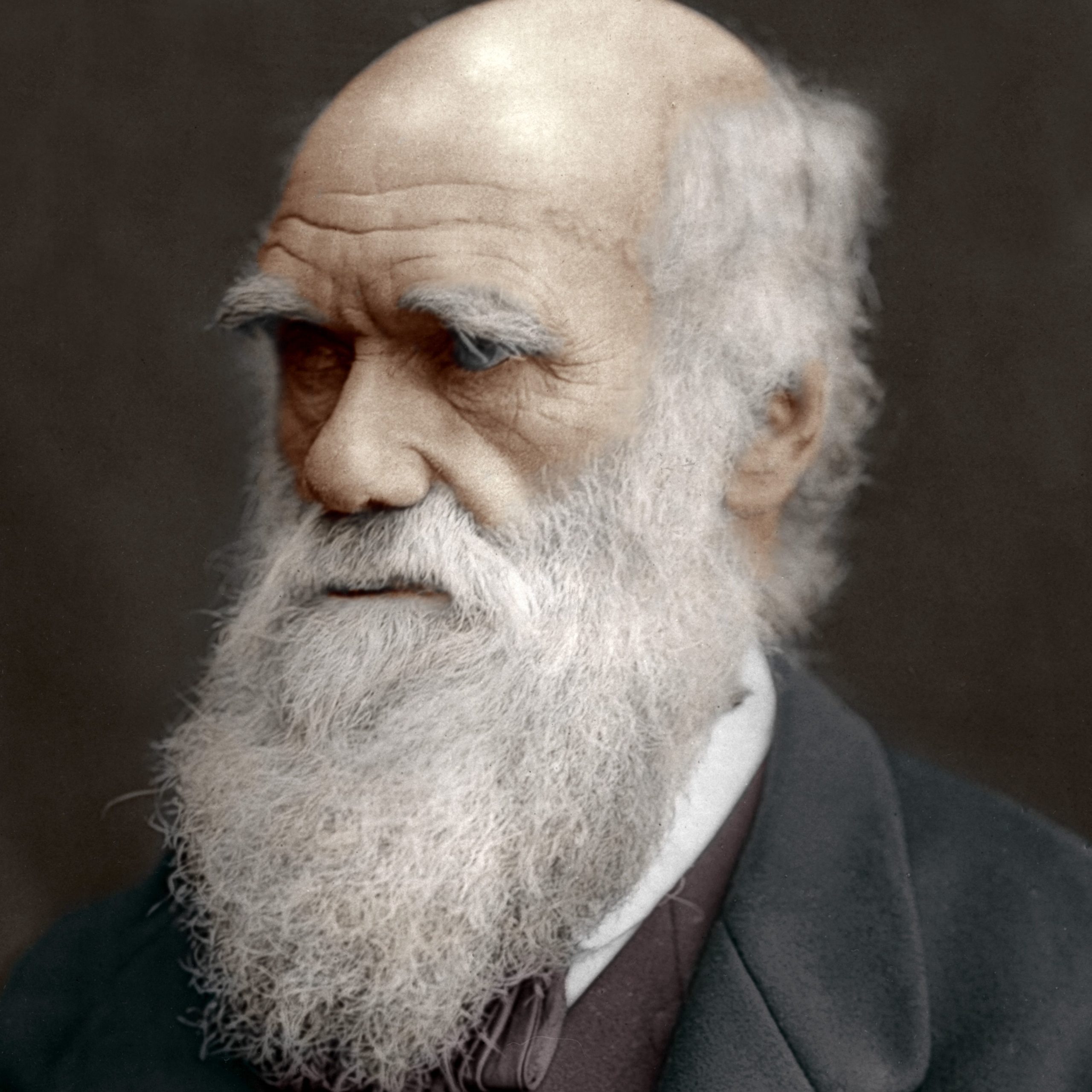

What about Point 3? Despite angry denials, this disparity is enormous – just as Darwin would predict. The loss of a child is devastating. Many parents who lose a child never emotionally recover. In contrast, most people get over the loss of an elderly parent in weeks – or days. Indeed, to be brutally honest, a notable minority of people actually feel better when an elderly parent dies. Never mind ungrateful children slobbering for their inheritances. A model child can still be relieved by the death of a parent living in pain, no longer able to enjoy life. Or a parent whose dementia has robbed them of their sense of self.

Why are people so reluctant to admit these truisms? In part, because they fear the bodyguards of Social Desirability Bias. Once you admit the obvious fact that the lives of the elderly are worth much less than the lives of the young, they’ll absurdly claim you favor murdering the elderly. Once you admit the obvious fact that people miss the elderly less than the young, they’ll absurdly claim that you don’t care if anyone over 50 drops dead. Whatever. A strict consequentialist will draw no fundamental distinction between killing and letting die. The rest of us, however, know that it is wrong to murder the miserable – but praiseworthy to get the most bang for your buck when you’re selecting charities. Or spending taxpayer money.

Another reason people are so reluctant to admit that the lives of the young are worth far more than the lives of the old, though, is pride. I just turned 50. Does this mean my life is worth much less than it did when I was 20? Hemming and hawing aside, the honest answer is yes. I’ve burned up at least 75% of the value of my life already. While I plan to savor my last 25%, do me a favor: If you ever have to choose between saving me and saving one of my children, save them.

Indeed, if you ever have to choose between saving me for sure, and saving one of my children with 10% probability, save them.

READER COMMENTS

robc

Apr 13 2021 at 9:49am

That describes my situation pretty well. My Father died in September of 2020. But he had been gone much longer.

zeke5123

Apr 13 2021 at 1:07pm

That happened with a grandfather of mine who was a surrogate father. It was bittersweet when he died. I of course was sad that I’d never get to speak with him again, etc. But at the same time I recognized that in many ways he died years before. I was happy for him that his torment was over.

robc

Apr 13 2021 at 9:52am

Deal. But I have one question for you? What percentage of saving probability should I burn up doing the calculation before acting?

Jim G

Apr 13 2021 at 5:20pm

Ok, but if I have to choose between saving you and saving the life of the child of someone you hate, what would be your probability – I doubt it would be 10%

Joshua Yearsley

Apr 13 2021 at 10:20am

Who cares? If we’re individualists, shouldn’t we instead ask them the question, “How much do you appreciate or enjoy your life?” And in many countries, especially the US, self-reported happiness follows a U-shape.

AMT

Apr 13 2021 at 10:46pm

My initial reaction was x= about 8, just based on a rough calculation of about 10 years of life left for each 80 year old, and 80 left for the 10 year old. I understand health rapidly deteriorates at a high age, but this graph from the economist seems strong evidence of hedonic adaptation to help equalize that (though perhaps it stops a bit short of the most important years).

Bryan could you explain why you think 1000 is more appropriate, if actual utility might not be expected to differ too much, even if health does?

Perhaps another wrinkle to consider, would your answer change much if the health issues one suffers in old age do not cause considerable pain, because of an ample supply of pain medication? I would thoroughly agree that if you want to do fun, exciting things like traveling the world and seeing exotic destinations you should probably do that early in life because eventually even walking will become difficult, but it is unclear that happiness will necessarily suffer significantly. Maybe people get a lot more enjoyment of occasionally seeing their grandchildren and great grandchildren than we might expect?

Henry

Apr 13 2021 at 11:10am

Hypotheticals are useful to help us organize our thinking, but what actually happens in real life situations? When the Titanic sank, the richest, most elite passengers actually stayed on board and gave up their lifeboat spots. Benjamin Guggenheim, fabulously wealthy, made sure that his maid got on a lifeboat, dressed in his best, and drank cognac in the bar while others got on lifeboats. Making personal sacrifices is not rare; my parents gave up a lot for my sake, and I don’t forget.

Maybe the tools of economic analysis are not useful for some human exchanges.

robc

Apr 13 2021 at 12:18pm

It looks like the tools of economic analysis reached the same conclusion as Guggenheim.

Don Boudreaux

Apr 13 2021 at 12:27pm

Henry: I’m not sure of the relevance of your Guggenheim example. Perhaps it is a counter example to Bryan’s point, but perhaps not. It isn’t clear to me.

But your example of your parents sacrificing for your sake clearly supports Bryan’s point. That example, contrary to what appears to be your intention in using it, doesn’t contradict it.

Phil H

Apr 13 2021 at 11:23am

This is all very curious. Do they not teach history where Bryan Caplan lives? All of his calculations seem fine on the surface, and I think many people would have been quite comfortable with them 200 years ago. For me – and I believe for most of us, consciously or subconciously – what makes the difference is the 20th century. Because in the 20th century we learned what happens when that kind of discriminatory logic is carried through to its logical conclusion, and we don’t like it. We also saw that when human ingenuity sets itself the task of being better than that, it succeeds triumphantly. So we decided to start taking seriously the ideas of the enlightenment, and to actually give every person the vote, and to actually treat each life as if it’s important.

This desire to pick and choose who must die seems Malthusian, cruel, outdated, and wrong.

Don Boudreaux

Apr 13 2021 at 12:35pm

Phil H: You seem to miss the context and relevance of Bryan’s point. Although he doesn’t explicitly say so, Bryan’s point almost certainly is to promote understanding of why a disease, such as Covid-19, that reserves the vast majority of its ravages for the old is not as big a deal as is a disease that kills an equal number of only young people – or, even, as a disease that kills an equal number of people randomly ‘chosen’ throughout the age distribution.

Whatever is the correct level of precaution to take against a disease that kills X number of only young people, surely the correct level of precaution to take against a disease that kills X number of old people is lower.

Phil H

Apr 14 2021 at 2:28am

Thanks, Don.

Yeah, I didn’t so much miss it as just not think it was worth engaging with. I disagree at a very basic level with BC; given that disagreement, we aren’t going to agree on the specifics of how the Covid crisis should be handled.

Here’s the nub of the disagreement. At a personal level, he’s right that the death of a 90 year old is not the same as the death of a 9 year old. But it is a mistake to think that this personal distinction should drive different handling at the policy level. On a personal level, when my friends’ grandparents pass away, I handle them and their sadness differently to how I would handle someone who’s lost a child. But on the institutional level, I expect the doctors to fight just as hard for the life of a 90 year old; and I expect the police to pursue the murderer of a 90 year old just as zealously.

Covid is a policy-level problem. Applying personal-level ethics to it is an error. BC is so far away from having a reasonable, working theory of public ethics in this post that I didn’t want to waste my time teasing out what his implications were.

BC

Apr 14 2021 at 4:38am

“I expect the doctors to fight just as hard for the life of a 90 year old”

That’s not answering Caplan’s question, which is about scenarios when must choose between a 10-yr old and a 90-yr old. If both need a liver transplant and you have only one donated liver, then which one should get it? Should age be a factor?

Monte Woods

Apr 13 2021 at 11:35am

Professor Kaplan,

Ex se intellegitur that parents are willing to sacrifice themselves for their children. In this zero-sum game, however, would you feel as equally disposed to sacrificing yourself for my children?

Paul Kowalski

Apr 13 2021 at 2:16pm

Probably not, because it’s also HIS life that he would be sacrificing, and so there’s an egoistical notion to either of the choices. 🙂

I wonder how the same question would look if the child were his best friend’s child – a more troubling choice to be sure.

Monte

Apr 15 2021 at 11:24am

Now the game changes, as well as Prof. Kaplan’s preferences. In this instance, he may be more inclined to sacrifice his life for the child of a close friend or a member of his immediate or extended family (sister, cousin, etc.). Or consider a non zero-sum game, where the pay-off involves some form of compensation for his sacrifice (ie. bucket list, cash payment towards his estate). The hypothetical becomes boundless.

Rigo

Apr 13 2021 at 12:02pm

“In all honesty, though, I’ve yet to meet a person who merits this charity. No oneresponds to the deaths of 10-year-olds and 80-year-olds with remotely equal concern.”

Allow me to introduce you to the last year of government pandemic policy.

robc

Apr 13 2021 at 1:18pm

??????

History is full of the old sacrificing themselves for the young, especially their children.

Alabamian

Apr 13 2021 at 2:16pm

History is full of the old sacrificing themselves for the young, especially their children.

Absolutely. And, as a related observation, finite resources always require rationing in one way or another. On some level, we are always required to evaluate individuals against each other along some dimension to decide who gets what. And the choice of system by which we do that can be better or worse at maximizing particular attributes that we care about. Such is the nature of policy. But none of that has to do with the moral value of someone’s life. That misunderstanding subsumes the entire idea of moral worth and substitutes for it the reified attribute for which you were selecting. At that point, the concept of moral worth ceases to exist as a bulwark on action. And that is a very bad thing.

It may well be the case that we, writ large, consider it a greater tragedy if a bright, attractive, and successful 30 year old with young children is killed in a car accident versus a 30 year old ugly single dullard with no prospects, but it does not follow from that the ugly single dullard’s life was of lower moral value.

MikeP

Apr 13 2021 at 1:27pm

“I was the logical choice. It calculated that I had a 45% chance of survival. Sarah only had an 11% chance. That was somebody’s baby. 11% is more than enough. A human being would’ve known that.”

Henri Hein

Apr 13 2021 at 9:08pm

Nice!

Ghatanathoah

Apr 13 2021 at 2:55pm

This seems like one of those moral quandaries where, even if consequentialism says that in principle the lives of children are more valuable, in real life scenarios we shouldn’t try to weigh peoples lives like that. Rule-consequentialism teaches us that there are a lot of acts that might be correct in principle, but in our messy real world they have too many second order effects, so we shouldn’t do them.

It’s similar to the classic question of whether or not a hospital should kill a patient and harvest their organs to save four people. Even if you think that is right in principle, in practice you should never do it because it would sow distrust in the medical system, which would ultimately cost more lives. Trying to weigh the value of different lives is similar. I think it can probably done in principle, but in practice it breeds distrust.

Andre

Apr 13 2021 at 5:08pm

And yet we clearly turned Covid-19 into a trolley problem where we turned the lever to save a large group of elderly and sick people, running the trolley onto the side track with fewer young people who died of suicide/homicide, lost a tenth of their childhood, or failed to get needed medical care and died as a result.

Sure, fewer died, but society still chose to kill them by imposing rules with obvious consequences.

Henri Hein

Apr 13 2021 at 9:12pm

I think it is important to keep this mind mind, but I also think Caplan covered this situation:

In your example, the victim is not even necessarily miserable.

Franz

Apr 13 2021 at 3:22pm

I tried the exercise on my mind and I got X = 20. Under substantial pressure I could push it to 100, but I don’t see how you can possibly get to 1000.

Also, I don’t know if there is any data available on this, but I’d be surprised X=1 received more than 10% of the the preferences. It could still be the modal answer, but only because the comparison is unfair, there are just so many possible answers and X=1 is such a strong focal point. My guess is that if you contain X to be between 1 and 10, then X=1 would not be the mode.

Which brings me to my final point. I agree that Social Desirability Bias dictates a lot of people’s declared preferences, and it will definitely push de median X down from what you or I would consider a reasonable number. However, I don’t think that there is a strong social pressure to declare X=1. Quite the opposite, I would guess that the social pressure would go the other way.

Jon C

Apr 13 2021 at 3:44pm

I agree with everything except the 10% part. If there’s ANY chance to save my kid, save my kid.

P.S. The first recipient of the Pfizer vaccine was 91 years old. No matter how long I live, that will never make sense to me. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-55227325

Bryan Pick

Apr 13 2021 at 4:42pm

While I think this post is broadly correct, there are some important factors it’s not considering. If we accept the goal of trying “to make the world as morally valuable as possible,” the number of years of life and how much that person is missed aren’t the whole story.

We evolved to feel much worse about losing a ten-year-old child than about losing an older relative partly because a ten-year-old child represents a major investment that came short of starting to pay off: if that child had survived a little longer, that child most likely would have started having children and would have started contributing to the group (hunting, gathering, support activities, teaching younger children). That’s a pretty intuitive explanation for why parents are more affected by losing a ten-year-old child than losing a two-year-old child, and more affected by losing a 17-year-old child than losing a ten-year-old child. (See “Couples at risk following the death of their child: predictors of grief versus depression” at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16173849/ .)

This is not what we’d predict if the short-term calculation of life years or healthy years remaining were the most important variables.

An older relative, by contrast, seems to have already mostly paid off in terms of contribution to inclusive fitness: their childbearing years have come and gone, and they’ve lost a step when it comes to using strength, endurance, and dexterity for hunting and production. But what remains is mostly how much value they add as teachers and caretakers. Humans have, for the vast majority of our history, gained a lot from our elders; having survived more uncommon events, they were a repository of knowledge that could prove to be the difference between life or death for younger members of the family/clan/tribe/society, knowledge that wasn’t necessarily passed to their children at a younger age because it was only important in rare situations, like what to do in a particularly bad drought year that disrupts usual patterns of gathering and hunting. In those situations, the group would need a knowledgeable elder more than it’d need a 10-year-old mouth to feed that could hypothetically survive many more years and produce a bunch of offspring if only that child could survive this dreadful summer.

Elders could also be trusted to look after young children while the younger-adult parents were engaged in productive hunter-gatherer activities that required too much attention, danger, or exertion (like persistence hunting) to bring the smaller kids along.

From that perspective, losing one elder may or may not be worse than losing a teenager, but losing too many of your elders could easily be a greater catastrophe than losing the same number of 10-to-16-year-olds, even though the immediate calculation of QALYs lost is lopsided in the other direction. There’s a cross-species comparison to be made here with what happens to groups of elephants that lose their elders (see “Effects of social disruption in elephants persist

decades after culling” at https://frontiersinzoology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1742-9994-10-62 which was summarized here: https://www.treehugger.com/elephant-society-needs-elders-study-suggests-4866532 cited in Henrich’s The Secret of Our Success).

Of course, societies may change in ways that change the value they place on elders. Perhaps as elders’ memories are more efficiently encoded for younger generations to access (in print and other forms), or the survivability of disasters rises due to technology and wealth, or elders are more or less available/desired as caretakers, or as a greater proportion of elders have dementia or other crippling conditions, we’d expect to see some effect on the society’s (or individuals’) values.

Bryan Pick

Apr 14 2021 at 1:28pm

On second thought, I think the elephant study cited in The Secret of Our Success might have been this one: “Severe drought and calf survival in elephants” at https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsbl.2008.0370 which was summarized here: https://newsroom.wcs.org/News-Releases/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/4981/Elephant-Elders-Know-Better.aspx

James

Apr 13 2021 at 6:03pm

When I read posts like this, I wonder why more economists are not lined up in opposition to abortion.

I understand that restricting access to abortion or outlawing it imposes costs on some people such as women forced to carry pregnancies to term and doctors who really wanted to be be abortionists having to go into other specialties but the losers are grownups and their losses are far less than the full value of their remaining years of adult life. Abortion takes away 100% of the value of the life of the unborn. From a consequentialist/utility tradeoff making/economistic point of view, this seems like a really clear case.

What am I not seeing? Is there any economist who has even addressed the question and put numbers on it?

Jasper

Apr 13 2021 at 7:46pm

You might wish to check out the work of Donohue and Levitt, whose paper you can find here. They were concerned with the causes of the precipitous drop in crime of the late-’80s through the 2000s, and found that legalized abortion accounted for almost 45% of it. The sad truth is that children that are most often aborted are the ones who are unwanted by their parents, and such children, should they be brought into the world, tend to have more unhappy lives with higher levels of mortality and a greater chance of turning to crime than other children. Remember that utilitarian ethics, carried to extremes, leads to the Repugnant Hypothesis that the universe should be filled as efficiently as possible with people (or animals) with just enough resources to survive and no more. While human life is of course valuable, I think it is better to have fewer, happier people than more miserable people. Hence the value of abortions – a mother knows better than an economist when it is time to bring someone into the world.

Andre

Apr 15 2021 at 10:51am

“a mother knows better than an economist when it is time to bring someone into the world.”

She already brought someone (the fetus) into the world. She just hasn’t given birth yet. Isn’t this the controversy? Your statement assumes one side’s conclusion.

“A mother knows better than an economist whether to give birth to a fetus” doesn’t sound as convincing.

James

Apr 15 2021 at 11:24am

That paper is fascination but it makes no claim that the reduction in crime was worth the reduction in life years for the aborted.

We could try the back of the envelope approach and see what we get. I think there is some standard view that the value of a human life is about $10 million. So multiply that by the number of abortions since it became legal in the US. Now value the crime reduction with FBI crime stats or whatever relevant data you like.

I do not have the numbers in front of me but it should be simple to establish an upper bound by considering the hypothetical situation where every single aborted fetus would, if carried to term, grow up to commit $10 million worth of crime, or a single murder. In this case, abortion is break even in terms of cost an benefit. If the fraction of aborted fetuses who would have risen to this level of criminality is anything less than 100%, then the reduction in crime is not worth the cost.

Mark Brady

Apr 13 2021 at 8:53pm

Two thoughts.

1. Bryan’s post, and the discussion that follows, don’t recognize how adults (and children) would respond to different rules. Depending on how the lives of 80-year-olds are valued in society, the rest of us would behave differently. And depending on how the lives of children are valued in society, the rest of us would behave differently. We may speculate how they would behave differently.

2. A fetus does not have any valuation of its future life. Eighty-year-olds do. Doesn’t this count? I also recognize that a new-born baby doesn’t have any valuation of its future life. Does this mean that we should discount the future life of such an infant compared with, say, a ten-year-old?

Henri Hein

Apr 13 2021 at 9:32pm

One consideration that seems to be missing from the analysis is human capital. Although the 10-year old has more potential, the 80-year old has more human capital. It’s the main reason soldiers are conscripted young. Sure, they are stronger and healthier on average, and perhaps also more psychologically malleable, but these differences are marginal between ages 18 and 30. The human capital is not.

I still think the sum total favors saving the 10-year-old, but there is at least one dimension in which the loss of the 80-year-old is worse.

This Landsburg post is also relevant.

Ben

Apr 13 2021 at 11:01pm

X= 1,000 (maybe more)

Not all 10 year olds will grow up to be productive (and reproductive) members of humanity- but exceedingly few 80 year olds will grow the pie/grow the population. Society is better off with more 10 year olds than 80 year olds (assuming all 11 to 79 year olds still exist).

Not advocating for elder-cide…but better to have a pyramidal shaped age distribution than a mushroom.

Didn’t we do some level of reverse of thos with covid? Lockdown the young to save the old?

Jens

Apr 14 2021 at 3:11am

You bring a lot of context and foreword to a simple question. That’s OK. But can also answer a different question than the one asked.

Jens

Apr 14 2021 at 3:03am

A couple of points ..

It makes a difference whether you decide from a position of involvement or not.

As an altruist or someone who values fame for selflessness, one might be willing to make personal sacrifices. The same applies to parents or grandparents; here one even makes genetic information more durable.

But in such a situation a “neutral” observer or judge would feel called to be differently charged with a search for law, equity or truth.

It is not immediately clear which of the two aforementioned roles would be given decision-making powers – without knowledge of future situations to be decided – if this could not be avoided. (Whether you can avoid it is a similar question of its own).

It is also the case that Caplan gave us information about his relationship to his descendants and thus about his personal will, which we cannot really assume when assessing the initial question (neiter about the personal will of the people involved nor about their relationship).

Another point is the question of the mode of rescue: Who is saved from what? So what is the answer to the question: Suppose you could either save one 10-year-old from not viewing tv for the rest of his life or losing a limb, or X 80-year-olds from immediate or close death. What value of X is morally indifferent?

BC

Apr 14 2021 at 5:28am

“Probably more like 1,000. I suspect that many readers will strongly object to this, but on what basis?”

A factor of 1000x seems like a lot. Suppose the live(s) could be saved by giving either the 10-yr old child or 1000 80-yr old seniors an elixir. (Suppose children require doses 1000x as large as that needed for seniors so there is no option to save the child plus some seniors.) I would be surprised if the child’s parents would pay more than 1000 seniors combined would pay for the elixir. For example, even if the seniors were only willing to pay $100k each — a fairly small sum to extend one’s life, even if one were quite elderly — then that would say that the parents would be willing to pay $100M. Even if the parents didn’t have $100M, suppose we allowed them to act on their child’s behalf to put the child $100M in collectible, inheritable, non-forgivable debt in exchange for the elixir. Would parents, acting in their child’s best interest, condemn their child and many subsequent generations into indentured servitude? Society currently considers such arrangements so immoral and inhumane that they are illegal.

On the other hand, maybe I’m wrong and Caplan is right. How could either of us know how much the seniors and child (or parents acting on child’s behalf) value their own lives? Determining utilitarian solutions seems to be 90%+ learning the relevant parties’ utility preferences, less than 10% implementing the actual utilitarian solution. There are so many factors that an individual might consider: health status, future life plans, happiness status, how many living relatives and friends one still has or expects to have in the future, expectations about the afterlife, etc. How could I or Caplan know all of this information, let alone the relative weights the individuals involved put on such information? The only feasible way to learn this information would seem to be to allow the individuals to communicate it through markets. If any third party tries to carefully consider all the relevant factors, they quickly run into the socialist’s computation problem.

David Seltzer

Apr 14 2021 at 6:27am

If I am a consequentialist, it seems actuaries and insurance companies have made that calculation. After all The die-away curve is exponential, capturing one’s accelerating decline.

MarkW

Apr 14 2021 at 7:23am

I don’t think evolution cuts as cleanly as you think. Until the 20th century, losing young children to disease was a near-universal human experience. Parental grief supposedly is greatest for a child who dies when nearly fully grown (and represents the greatest lost parental investment).

As for 80-year-olds — although their health may not be great, reported happiness levels are very high (higher than in middle age). Also, the life expectancy for an 80-year-old woman in the U.S. is another 10 years — a non-trivial fraction of 69 year life expectancy for a 10-year-old. Life expectancy for a 50-year-old in the U.S. is about 30 years for a man and 33 for a woman, so you really haven’t already used up 75% of your life (the longer you’ve already lived, the greater your expectations for your overall lifespan). Your 100-1 or 1000-1 ratio is just not supported by the data.

Lastly, this way of thinking leads to the conclusion that a life at a given age in an industrialized country is worth more than one in a poor country (and a woman’s is worth more than a man’s and a white person’s life is worth more than that of an underprivileged minority) due to greater remaining life expectancy. Do we really want to go there?

Rob

Apr 14 2021 at 8:35am

Social desirability bias is one possibility. But I think there’s another possibility Laziness. Defending that 5 is a better answer than 7 is tricky, it requires maths, and data that I’d have to look up. On the other hand 1 is easier to defend (albeit badly).

A Country Farmer

Apr 14 2021 at 9:32am

Is this whole blog post a coded message that your family is being followed by a dark cabal ;-P

Rafe

Apr 14 2021 at 10:38am

This is why intellectuals are the first to go when governments go astray, every life is unique regardless of age. To make an economic appeal based on age selection is ego driven, aspects of culture downfall. My life at age 76 is every minute worth as much as any 10 year old. And frankly, the level of parental care and guidance in bringing up their children is poor to lousy, the perfect example is the parents of Mr. Trump.

OH Anarcho-Capitalist

Apr 14 2021 at 11:23am

Agree- I’ve lost a sister (73) to Alzheimer’s and my mother to congestive heart failure after years of cognitive decline. Those were blessings based on what their lives were like at the end. I think fondly of both occasionally.

A girl I dated in college was murdered by a friend’s step-father when she was only 19. I carry her death with me to this day – it’ll be 40 years ago come 2023…

Anon

Apr 14 2021 at 1:03pm

do me a favor: If you ever have to choose between saving me and saving one of my children, save them.

Don’t worry Bryan, I’ll do just that

Pete Smoot

Apr 14 2021 at 1:29pm

Amen, brother. I’d be puzzled by any parent who said differently. My kids are 20-somethings, embarking on a decade of growth, transformation, and excitement. Dating, marriage, (possibly) kids, jobs, graduate school, vacation adventures, and so much more. I’ve done all that. I’d much, much rather let them experience it than save myself.

MarkW

Apr 14 2021 at 3:20pm

Amen, brother. I’d be puzzled by any parent who said differently.

Sure. But I’d be very surprised to have Bryan also willing to honestly declare ‘if you ever have to choose between saving me for sure, and saving any one child on Earth with 10% probability, save them.’ So this is not about the relative values of the lives of 10-year-olds and 50-year-olds, it’s about the extremely high value that parents place on the lives of their own children, but that’s it.

Daniel Pratt

Apr 14 2021 at 6:58pm

Yes. I’m 58 and I don’t know what the number is but it is much higher than 1. You might say I have 20-30 years left, but the young have so much more potential than what I might contribute over the remaining decades.

Michael Gray

Apr 14 2021 at 8:18pm

I draw your attention to Don Boudreaux’s insightful post on Cafe Hayek earlier this month, “Take Precaution Against Hypotheticals”. This is a pointless exercise.

Monte

Apr 14 2021 at 10:03pm

Controversial or provocative blog posts are a very effective way to generate more comments. It’s a vanity metric.

Doug

Apr 16 2021 at 1:47pm

Another consideration is that there’s diminishing marginal returns to years lived. Life in youth is more vivid because most experiences are new. As we age and live through more, each passing day tends to be filled with fewer novel experiences and more monotony.

Psychology has confirmed that older people perceive time as passing at a faster subjective rate than young people. Psychology has also confirmed that this is largely due to the decline of experiential novelty in day-to-day life.

A 60 year old may have a quarter of the life left as a 10 year in terms of chronological time. But in terms of subjective time, the 60 year old probably may have less than 5% of the time left as the 10 year old.

Eli

Apr 17 2021 at 7:28am

I notice some arguments in the comments making (something like) the conjunction fallacy. Every young life will one day be an old life too, so whatever value an old life has a young life also has that plus more.

Erik

May 2 2021 at 9:47pm

FWIW I distinctly remember that what the Swedish state would pay as compensation for anyone who had received HIV infected blood transfusions (looong time ago when HIV was new so to speak) was much much lower for older people at a falling rate with babies receiving the highest (absolute values were very very low compared to what you may expect in a US context). Not a factor of 100 or 1000 I think but significant. Some grumblings, but mostly from sons and daughters of older victims with possible selfish motives.

Comments are closed.